A Conversation With.. Eddie Kramer

This legendary studio guru now lives in Toronto and is playing a pivotal role in the transformation of the El Mocambo. In this wide-ranging interview, he discusses his early days in English studios, working with Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles, Woodstock, his passion for music photography, and much more.

By Bill King

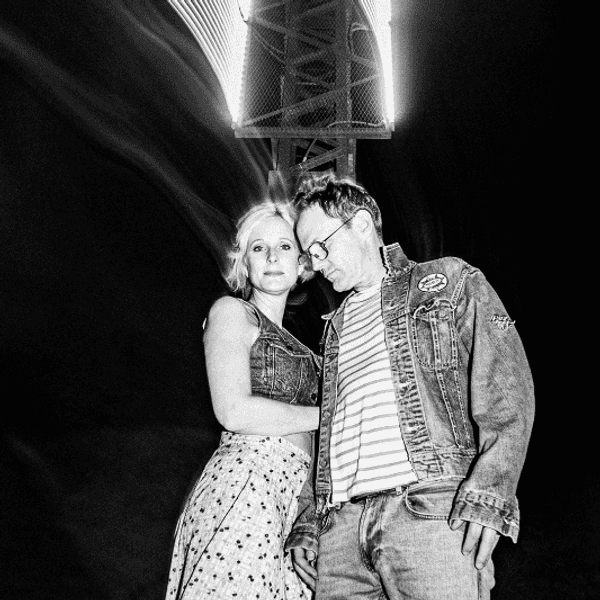

I’d been conversing back in forth with music man, Greg Godovitz the past couple years about cornering a music legend, recording engineer Eddie Kramer, for a sit-down interview. Greg and Eddie are tied up with the El Mocambo revitalization work. Eventually, the stars aligned, and Eddie conceded to do my Thursday morning interview show at CIUT 89.5 FM.

Any musician with just an ounce of audio curiosity would have bled to have Kramer record them. Kramer’s name resonated as loudly as the rock musicians whose names grace the front cover of so many new releases from the '60s on. He is the Picasso of sound reproduction. The tracks are bold, clean, and mixed with such precision you knew the escalation of time would never diminish their quality or artistry.

How do you pack one’s life history into fifty minutes? You can’t, by any means, so I chose to focus on the early years, Woodstock, Hendrix, photography and Kramer’s role in reviving the much beloved El Mocambo.

When I mentioned Kramer was coming in to my son Jesse, I saw in his eyes that ‘you’re not leaving me out of this’ look. Jesse has read nearly every book on contemporary music; from bios to studio to the good and bad of the business of music and is becoming a walking encyclopedia. Of course, he was coming in.

My apologies to Greg. I had to shorten this transcription from 9,000 words to near 4,000 and couldn’t include talk about the remix Eddie did of Greg’s early work. Another day, Greg, and many thanks.

The history here is the Beatles, Bad Company, David Bowie, Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, Kiss, Woodstock. It’s the history of contemporary music going back to the early '60s’ You live here now?

I'm proud to be a Torontonian because you know, living in LA. for about fourteen or fifteen years your blood gets thin, and when you come to Toronto you really have to put on piles of clothing to stay with it. We love it. We love Toronto very much - in fact, we can get on the streetcar and come in.

We sold our house, we sold our cars, we sold everything in L.A. and moved here, and we love it. The fact that you can just walk around and everywhere is great. And you stay fit, and the people are rather nice.

It gets better. You know what caught my attention before the show. DJ Dave James was just finishing up his dance music show and you are absorbed in his tracks. Then we start playing some Roy Hargrove, my theme off the top of my show, and you shift gears and become even more animated. Music touches you in so many ways.

It always has. I grew up studying classical music as a kid. By the time I was three or four I was really playing the piano. I think I had my first piano lesson when I was probably about four years old and continued studying classical music all the way until I left high school. In fact, my last three years in high school I dropped math and went to the South African College of Music and studied music instead. It was a weird thing, but I was able to get permission to do that. But they all thought I was completely crazy.

My mom and dad were wonderful. My late father was an amateur violinist, and he always encouraged me to play. Some of my earliest memories is standing up on a little stool, and there was a radiogram or a gramophone as you would call it and it played stacks of 78s in a row. It would be let’s say, the Brahms B flat Piano Concerto stacked up, and I knew at an early age by looking at the labels what record it was, and then I would just sit for a moment then stand up in the chair and conduct. Which was kind of stupid.

You must have made a decisive turn in your teens and thought I've got to get on the other side of the instrument and capture what I’m hearing?

I think it goes back to this early childhood where apparently in South Africa where I grew up, the voltage is 240, the main voltage, and when I was about three or four I managed to stick a steel knitting needle into one of these sockets, and it threw me across the room. True story. It threw me across the room, and my dad picked me up and walloped me and said, ‘What the hell did you do that for?’ I haven't been the same since.

I always had a fascination with electronics as a young teenager but there was a moment in time when I was thirteen or fourteen, I heard jazz.

A friend of mine introduced me to jazz. I started listening to Charlie Parker and Oscar Peterson. It just changed me. My whole musical direction shifted from classical, although it's always been based on classical, but I just went, ‘Whoa Jazz’. This is happening you know. My dad was so pissed off at me.

Much to his chagrin I really got into boogie and jazz and started playing that and then the classics went down the toilet. That was the shift in my career. Also leaving South Africa in 1960. After all the Sharpeville riots and everything because my dad was very left wing - he said 'we got to get out of South Africa' and we emigrated back to England. My mum's English. She came to South Africa in 1939.

Moving to England in 1960 was a critical moment because you can imagine the scene there was just bursting, and then you see the Beatles on TV for the first time. Holy, look at those guys. Check this out. And then by 1962, I was in the studio as a young punk engineer. I just said, ‘yeah’, that's it, this is what I have to do.

Jesse King: When you first started you were doing classical recordings working at Pye Studios. How did that transition from working in that kind of atmosphere inspire? Were you assisting then?

I was an assistant engineer and I thank God I had the best training guys around and the best engineers. There was a guy - Bog Walger - and we're at Pye Studios and one day we're doing the Kinks, the next day we're at Town Hall recording a ninety-piece symphony orchestra with three microphones, so I got this fantastic classical training as well as this rock thing. It was crazy. There were no schools for engineering. You just learned by making mistakes.

Jesse King: Did you have a similar situation at EMI? I read they had everything in position and you even had to wear the lab coat. They never moved the drums. The new guy never had this freedom.

No, every place that I ever worked was a very independent kind of studio. From Pye, I had my own studio for a while. That was fun. I was cutting tracks on my own and after that, I went to Olympic Studios. And that's where the magic happened.

Jesse King: When was that?

It would be late '66.

Bill King: And what did Olympic have that was different?

Well, it was like it was a crossover point because Olympic was a famous studio before it became ‘the Olympic’. After that they were doing stuff with The Troggs and a lot of commercials. It was only four-track at that time, but they were about to move from Cotton Street which is right in the center of London to Bonds, which is a little suburb and they had built this gorgeous new facility which is in an old movie house and that's where I started to record Jimi Hendrix and The Stones and all the rest. That's where the magic happened.

Bill King: I'm still fascinated with the '50’ and '40s recordings with Sarah Vaughan and others. These recordings sound magnificent. Even the other day we listened to Frank Sinatra at the Sands with the Basie Orchestra. I still don't know how they did that.

This is fine, fine engineering. You know you're trained to record mono. You get the balance right on everybody. And that's your training and it's embedded in my brain. You start with mono then you go to stereo then you go to a three-track then you go to four and then when you come to America you jump from four to twelve-track or sixteen and it's like, what?

Jesse King: That was the Scully machine that you were not a big fan of I think.

Well, the Scully twelve track was the biggest piece of junk ever. However, the Scully eight-track was wonderful. Those are the two Scully eight tracks I took up to Woodstock to record which is another story for another day.

Bill King: Woodstock, I would figure that was a significant challenge?

That is a mild understatement. I've always said that Woodstock for me was three days of drugs and hell. And it was incredible.

I get a phone call from the film company and they say, “would you like to record this? We got this festival up in Woodstock. Jimi Hendrix is going to be the headliner and you know we do live recording stuff. Would you mind coming up and taking care of us again?” No problem.

I remember it was a Friday morning about 4:00 a.m. 3:00 or 4:00 o'clock and this young lady beeps. ‘Come on, we’re driving up’ and it’s a two-hour drive or whatever and we get within a mile of Woodstock and you can't go any further. We parked the car on the side of the highway and walked the last mile. Near this ridge I'm looking down at Woodstock and it’s 6:00 a.m. and the sun's coming up. You can see the stage and outlined are these cranes on top of the stage and they’re still building it and I'm looking at it and thinking in about three hours I'm going to have to be recording and it looks like a construction site. I’m thinking there's no way in hell that's going to happen, but it did. It was the most incredible experience I think for everybody who was there. Fortunately, there was a collection of great tech guys from the Fillmore East. The Fillmore East was where I used to record all the time. It was a great, great venue. There was an eight-track in the basement that I used to use to record with.

All of that gear plus all the tech guys from the Fillmore came up with their sound gear and Bill Hanley, who did all the sound. I was in a tractor-trailer behind the stage about two hundred yards away. At a certain point all the communication between myself and the stage guys went out and I'm standing there at the side of the tractor-trailer waving my arms going 1, 2, 3. Nobody knew which mic line was going. It was amazing.

I remember standing on the stage just before it started and looking out at the sea of people there must have been a half million out there and Bill Graham from Fillmore standing next to me and he said, ‘Eddie if these people decide to riot we're screwed.’ Thanks, Bill, I'm going to go back to my truck.

All of the artists who played the festival elevated their game. And look how many bands that were doing decently you know, like Santana, who all became icons because they just performed the magic at Woodstock. After that fact, look at all of the exposure they got.

Bill King: I think before that Monterey Pop sort of put Otis and others on the map too.

And Jimi. That’s a little bit of Woodstock.

Bill King: The new Hendrix?

This is an album that we put together last year that took us a year to do. It’s myself, Janie Hendrix and John McDermott and the three of us. We do all of Jimi's albums. There are three albums, and this is the last of the trio. Billy Cox and Buddy Miles and there is also Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell on this as well.

Most of this album is Jimi live in the studio. These tracks he was doing were not the final, final, final master but so close yet it shows this other side of Jimi. This is '69.

He was recording a lot of the stuff and this was his year of transition and experimentation. He was trying to find this new direction and you could tell it's funky, it’s R&B, it’s blues, it's got all the rest of that stuff and it's hard driving and the performance on this is just mind-blowing. He's got all of the stuff on it. Not only the bass lines and what Buddy is doing and what Bill’s doing, but Jimi at one point in let’s say, ‘Mannish Boy.’ is singing in unison with the guitar doing all that and playing rhythm and lead which is his traditional way of doing things. When you listen to the guitar parts they're like impossible to play like that. I don't know anybody who can play like that.

Jesse King: Was this a multitracked session?

This happened to be sixteen tracks because it was '69. It was at Record Plant, New York City and Jimi was on his own in '69. What was I doing? I was building Electric Lady Studios for him. I was doing Zeppelin, Woodstock and all of that nonsense. But it was basically Jimi trying to find new directions. He would go to Record Plant. He’d go to the Hit Factory or whatever studio he could get into. He was living in the studio and thank God he was, and the tape was rolling.

We got these wonderful tracks. Just imagine Jimi would be at the Record Plant on 44th Street on 8th Avenue and then two blocks up Eighth Avenue at 46th was the Scene Club which is where he'd be every bloody night finding out who was gonna jam. He would be jamming at the Scene and then come back to the Record Plant dragging fifteen or twenty people with him. It was an amazing scene. Imagine Jimi walking down 8th Avenue with the hat and an entourage. He’d stopped traffic literally, and then just walk into the Record Plant they were ready for him. Bang. In fact, that’s the way ‘Voodoo Child’ was done. Who's in town?

Steve Wynn was in town and Jack Cassidy and they're jamming over there at the Scene and he drags their asses back over to the studio and its midnight and we're all set up with the drums. They weren't just thrown in a corner. They were specifically where I placed them. The amps are all set. Headphones set. Jimi walks in with the guys. One rehearsal, one take ‘Voodoo Child’ done and tested live.

You can hear the Fender amplifier he was using, and Fender Showman double stacked, you know ten eight-inch speakers and that sound of that amp you can hear is so different than the Marshalls. And when those opening notes start, and you hear his voice and that's live on the floor, and that’s why it sounds like it does.

There were no egos involved. No managers saying,’ hey you can't do blah, blah or you can't have this.’ These are a bunch of guys who love each other.

On this new album, it's all of Jimi's friends. There are two tracks on this new album, Both Sides of the Sky with Stephen Stills. In fact, there's a track called ‘Woodstock’ on this album.

Stephen Stills comes running into the Record Plant one night, ‘hey Jimi, check this out. I've got a song and it was written by Joni Mitchell and it’s called ‘Woodstock’. He said, ‘do you want to play it man. Come on let’s jam.’ They jammed on the song. Jimi plays bass then later switches to guitar. And this is like the demo before it was released like maybe six months later. When you hear this track you go, it's what Crosby Stills and Nash took from what Jimi and Steve had done and turned it into the final version.

Bill King: A moment of truth here. Noel Redding? It's been said his bass parts were replaced by Jimi’s own.

Not true. What is true is the fact that Jimi loved to play bass and Noel would get really really pissed off. He would go over to the pub and get drunk and always had a little bit of a chip on his shoulder about it. I loved Noel’s playing. I thought Noel was an amazing bass player for that trio.

Jesse King: I wanted to mention not only is the album out but there's also vinyl. And I think this is key for collectors.

Absolutely. This album Both Sides of the Sky, the vinyl is phenomenal. 180-gram vinyl and it is just gorgeous.

Jesse King; The artwork is phenomenal. It's very much at peace with that time.

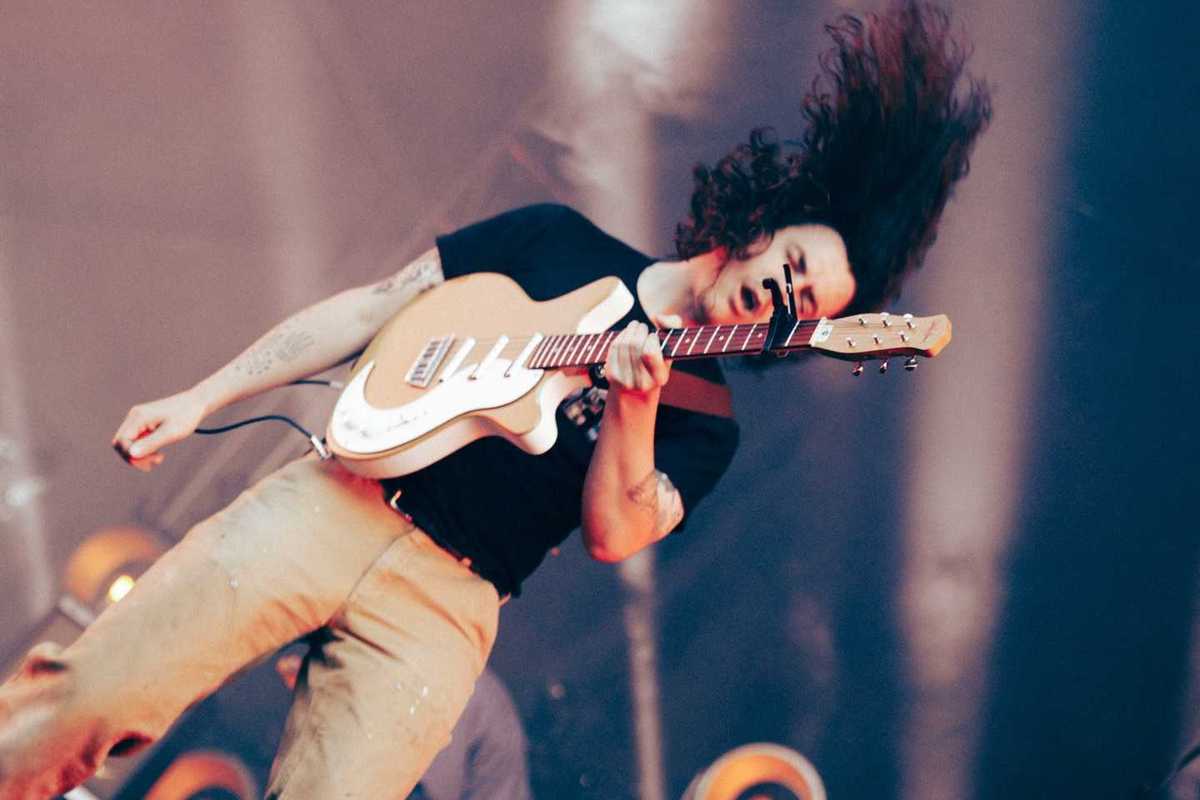

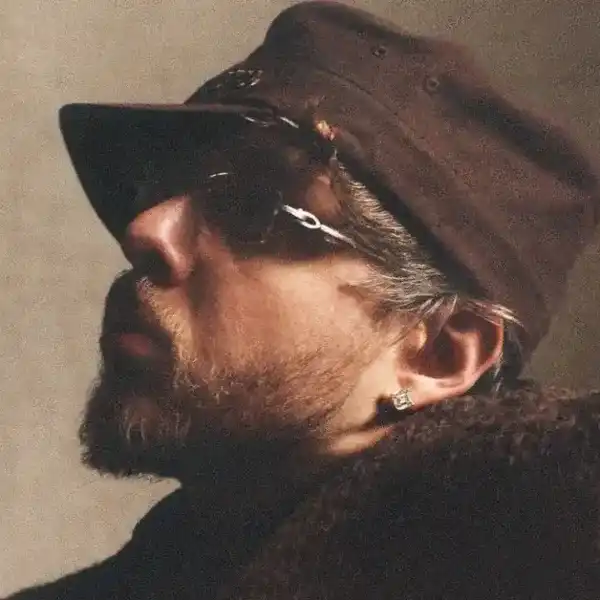

Bill King: We both share a mad passion for concert photography and I have enjoyed going through your site and your gallery. First camera?

I bought a Pentax camera an Asahi Pentax in 1967 from one of the engineers and started taking pictures immediately, just experimenting. The camera sat right next to me on the board on either my left or right side, I can’t remember now. I'd be mixing and grab the camera and swing around, ‘Hey Jimi.’ Thank goodness because like I said before about managers and all the rest, there was nobody to tell you don't take pictures and the guys would say ‘yeah, just Kramer with the stupid camera. Don't worry about it.’ Nobody bothered you. I was able to get these lovely shots of Jimi in the studio or the Stones or a Keith Richards.

Bill King: There's a great Keith Richards. I mean that's the Keith Richards from the 60s we remember.

That shot of Keith sitting at the piano or the one he's ad-libbing and he's staring at me - like this is a favourite.

Greg Godovitz: It's also about the casual photograph. You took that picture of the boys Zeppelin dancing outside. That's it. That's a classic picture. You caught them having fun.

When we were in the studio, we had fun no matter what. If we weren’t having fun there was no point in doing it because we just loved to record, we loved to make music and that to me is the joy of it. Still, today, if I'm not having fun, I don't want to be there.

Bill King: The El Mocambo? Everyone wants to know what’s going on!

I so remember being there in 1977 recording The Stones.

The place was purchased, and I was asked to come up and have a look and see whether I wanted to get involved. I looked at it and I said OK, I'm going to do this, we're going to put a studio in here. I wanted to bring in John Storyk, my oldest and dearest friend. He and I did Electric Lady for Jimi, OK. And that's the reason. WSD Group, which is the architectural firm, is probably one of the largest ones in the world and one of the better ones. It’s almost there.

We've taken about two and a half years so far and basically destroyed the entire building and took it down below grade and built a brand-new building on the inside. All we kept was the facade and the side walls and we underpinned the entire interior. There are now two venues. One on top of the other.

You remember the old El Mocambo? It had about a ten-foot ceiling. It's now twenty-six and a half feet high with a balcony running around top side and it's going to be the preeminent and predominant facility in North America. They are soundproof rooms. Both are completely isolated so that I can record the two venues at the same time with live streaming.

I have a special room on the third floor looking down on the room. This is like Abbey Road. We have the same board, a beautiful Neve vintage board looking down at the stage and five 4K cameras and Go Pro's - the whole thing and live streaming 24/7.

Bill King; Lastly, you did two tracks for the Beatles.

I did, ‘All You Need Is Love’ and ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man.’ There's a funny story.

I recorded with my boss this track, ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man. We heard the Beatles were going to come in and I was, ‘oh geez, the Beatles, we're going to show them.’ Why did the Beatles come to Olympic Sound Studios? They couldn't get into EMI or Abbey Road. That's the reason. It was booked all the time. Particularly for the Beatles, they were royalty.

They come in and we cut the track. We start at 7 o'clock at night. We finish at 7 o'clock in the morning. It's tracked, overdubbed and mixed. Thank you, out the door. I get the phone call from the front desk. Eddie, the Beatles are coming in again. Oh boy, rock royalty. Here we go.

John sits in the producer's chair and pulls out an acoustic guitar.’ ‘C'mon lads, we got to do this song for TV - it goes like this’, and he starts strumming – “All You Need is Love”. He’s pitching and singing right there.

The band walks in and goes directly into the studio. George walks over to the harpsichord and says, ‘It's all right, bring a microphone over here quick.’ Paul McCartney walks into the studio and goes, ‘hey, what’s that? It’s a string bass. It was my boss’s; he's a jazz player. ‘I'm going to play that’. He picks up the string bass and says, ‘quick microphone on here’, and that's how the session started, I'm thinking, panic, panic, panic. I go over to the patch bay and patch the microphone off the producer's desk into all the headphones, so John could sit next to me and strum the guitar and sing to the lads out in the studio. He’d never done that before. He goes ‘1,2,3’ - we're rolling tape right from the beginning, you know half an hour of tape time,15 ips, I hit record, bang, ‘All You Need is Love’. They go through the first take, then ‘two, three’ and they just keep doing it and doing it until we get to the end of the tape. It must be about eight or nine performances, some false starts. ‘All right lads - come back in’ and could you wind back from the end, right?’ Playback. Everybody smiles, ‘Yeah, it was great. See you. Bye!