Bill King: The Tony Bennett Interview

It’s heartbreaking anytime news comes revealing one of our heroes is being robbed of their gifts.

By Bill King

It’s heartbreaking anytime news comes revealing one of our heroes is being robbed of their gifts. Hearing our beloved Tony Bennett had been battling Alzheimer’s since 2016, growing distant and further inward, is in line with the epic consequences of our daily lives. Passing at 96 is not unexpected or disruptive. It’s about the quality of life. A life lived to the max.

Bennett made good of his later years. Seventy and on, collaborating with Cindy Lauper, Lady Gaga, Christina Aguilera, John Legend, Carrie Underwood, Stevie Wonder, - the most memorable, Body & Soul with Amy Winehouse.

In 1993, I conducted a marvellous interview with Tony Bennett, one I would repeat to my vocal students for years. I found him forthcoming and informative. It wasn’t a pop star mishmash of gibberish but a revealing conversation about art at its highest level.

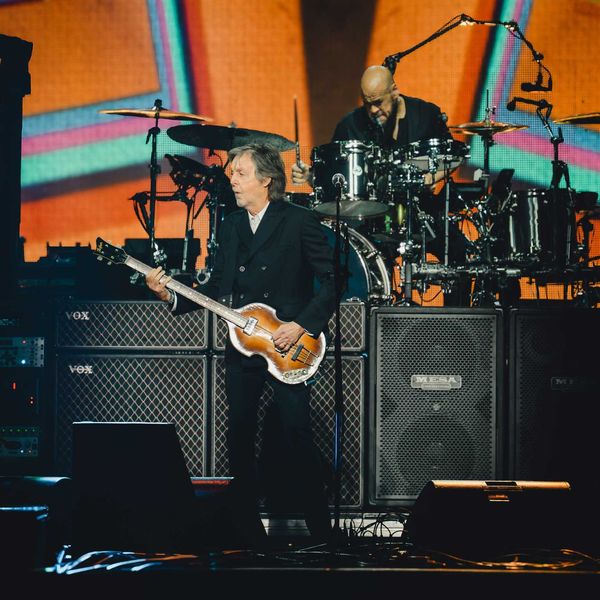

In 2009, I could photograph him in concert at the Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier de la Place Des Arts in Montreal. Going in, I knew this would be a battle zone. The money shooters would be there, so my strategy was to arrive early, stake a position and hold firm. 300 to 400mm lens flanked both sides of the stage. Even a couple of point-and-shoots jostled for visual territory.

The stage was a shooter's delight — stark, no microphone stands, music stands or galley of musicians. In fact, the players were far enough back to allow Bennett space to jog half a mile if he chose. It didn't matter which side the photographers positioned themselves; the man would stroll there in a matter of seconds.

The show opened with Bennett's daughter, Antonia, who, for her part, gave a fair reading of the material. The possibility of her father's performance being cut short sent a wave of fear through our photographer minds.

Bennett arrived and showered his daughter with kisses and hugs. Light shone on the man like a ray of gracious sunshine. One could record every detail, from the shoeshine to the broad, loving smile. And the voice, my goodness, what a voice! It yanks at the nervous system and toys with the soul. Bennett then walked toward us, hands held high — paused — smiled, then released a big, earth-cracking note. Shutters fired — click, click — again and again.

This shoot was easy. The music poured out in enormous waves, flooding the room with warmth and vitality. I love this man!

I observed how Bennett commanded every inch of the stage — a slow walk to the right, a turn, a slight hand gesture, a slow turn. Then his eyes rise upward, glistening in the spotlights. As if on camera cue, he returns, as if he had read our minds.

The third song was a ballad. By now, I was exhausted — not from the number of spent frames, but from the emotional intensity Bennett compressed into every song. I mostly stood, humbly watching. After an abbreviated solo, I witnessed the veins in his neck gather. The face looked muscular like a weightlifter squeezing a world record from one last lift. His voice then rose to a bone-crushing intensity. - With a sudden movement, I shook my head and wiped the moisture aside. The note eventually lifted, leaving the audience screaming approval. Meanwhile, the other lens jockeys headed towards the exit, loaded with plenty of images. I felt a bit embarrassed, as though I had folded under pressure. Then I saw my partner Kristine clutching a Kleenex, gently dabbing her eyes.

At 89, Bennett is just as vital and interesting an artist as any crossing the big stage. Here’s our memorable conversation.

Bill King: You’ve had a remarkable year, beginning with a Grammy for your tribute to Frank Sinatra, Perfectly Frank, and now the release of Steppin’ Out, a tribute to Fred Astaire. Is this one of the most fulfilling periods of your life?

Tony Bennett: Yes, it is. Producers often try to change the creative instincts of performers instead of trusting them. They’ll want you to do a quick novelty song or something silly to sell records immediately. A good artist avoids that.

We did Steppin’ Out and Perfectly Frank, as they say, “unplugged,” I’ve been “unplugged” for years. We just did it the way we know how to do things very naturally. Winning the Grammy was a very gratifying experience because no producers interfered with this project. The fact that we were able to do the album uncompromisingly and win in an age of heavy metal, rap and hip-hop is very exciting.

BK: How important was it for great composers like George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and others to have Fred Astaire introduce their songs?

TB: From what I understand, they wouldn’t make a move without Fred. His colleagues mention it, and so do the history books. He was part of the Golden Era. They respected him so much. He would bring shows in, not just songs. This was way before he did films and was on Broadway.

It’s interesting that not one of those songs hit the charts, yet they are heard internationally. They’ve become our ambassadors all over the world. If I sing Dancing in the Dark in Japan or A Foggy Day in London Town in Italy, everybody recognizes them as American songs. Like jazz itself, the cream rises to the top.

BK: It’s been the jazz players who have kept these songs alive through all the changes that have occurred in popular music.

TB: Yeah. All the famous ones — Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Coleman Hawkins, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and now Wynton Marsalis. There are so many artists: Sarah Vaughan, Billy Eckstine, and Duke Ellington. All of them interpreted those songs.

BK: It speaks a lot for the dynamics of an inspired composition.

TB: They are our tradition. We are such a young country and don’t realize it. We’re always craving something new, something that will be bigger than the Beatles or Elvis Presley. The industry just wants the big cash. Businessmen are blinded by the fact that all they want is more.

Jazz deals with the truth with honesty and sincerity. When people hear it down the line, even 2000 years from now, we’ll be hailed for giving the world some of the most beautiful music it’s ever heard.

BK: Do you think any of the songs in the last 15 to 20 years will have the same kind of longevity?

TB: I’m positive they won’t. There are just a few by people like Stevie Wonder, Billy Joel, Michel Legrand, Alan and Marilyn Bergman, Stephen Sondheim and Burton Lane — they are all great composers of mature popular craft, but they aren’t played on radio.

Everybody’s hyped up. This is the age of obsolescence. People want something that will increase sales.

BK: Are you an artist who lives in the recording studio or one who devotes the bulk of his time to pre-production?

TB: I spend time preparing so that when I go in, I do it fast. I spend months in preparation. I memorize everything. On the latest album, I planned the sequence of the songs instead of waiting until later. We just went in and started with the first tune and went straight through for two and a half days.

I road-test the songs beforehand. I want to see how they communicate with the audience, where the tune should be placed and what kind of concept it should have.

BK: How many songs did you record to arrive at 18?

TB: I did 24. I took Fred Astaire’s advice: whenever you have an act that feels perfect, pull out 15 minutes, no matter how good it is. The reason is to avoid staying on stage too long. I feel a record has to be the same way. You don’t want to be predictable or monotonous.

BK: Do you have a philosophy for linking songs together?

TB: I look for songs that uplift the human experience.

BK: Pianist Ralph Sharon has been with you for over 30 years. What has made this a perfect match?

TB: He’s my favourite musician. He’s the best colleague a guy could ever have. I just love being with him. He’s very intelligent and doesn’t throw it out at everybody. He’s very understated but very educated.

He grew up in Britain and was on the top of the jazz magazine charts there — number one for 12 years. He used to play piano for Ted Heath, who had the most famous band in England. Ralph also did a lot of movie scores. He’s a jazz player who also loves the public and likes to entertain them.

As a result, he’s very good at selecting songs. He’s found all the songs for me in the past 30 years. We consider ourselves tunesmiths and collaborate on introducing songs. We’ve introduced 135 so far; out of that, 50 of them are real blockbusters. Everybody, musicians and singers perform them now.

BK: You find jewels like Drifting.

TB: Ella Fitzgerald suggested I do that song. And you know, when Ella suggests a song, you’d better give it a listen.

BK: What makes an accompanist like Ralph Sutton invaluable to a singer?

TB: I consider those guys high artists. When I say those guys, it’s just a few people who really know how to accompany, like Tommy Flanagan and John Bunch. There are just a handful who really know how to play behind a singer. Bill Evans, of course, was just ideal.

BK: Do you have to be a great soloist?

TB: It’s someone like Count Basie, another great accompanist, who made all of his musicians sound magnificent. It’s a gift that’s part of their nature, where they want to help other cats out. There’s a generosity about them. They sublimate themselves to make everybody else sound good. I think that’s a wonderful quality.

I think they are high artists who aren’t respected enough because they’re in the background, but that background is what makes the whole thing happen. It’s like Jo Jones, who took a newspaper, wrapped it up backstage at Newport, and just hit his knee and kept time, and the whole band knew it. Everyone picked up on it. It became the best Ellington live performance record ever made - and it was just done with a newspaper.

Some guys play too much, and it interrupts the singers. You’ve got to breathe with the singer. You’ve got to know every move the singer is going to make. Ralph knows me like the back of his hand. He knows what I’m thinking from phrase to phrase.

BK: A vocalist like Shirley Horn understands herself so well it would be impossible to find a better accompanist.

TB: I love the way she sings. I heard a cut she recorded recently called Too Late Now by Burton Lane and Allan J. Leonard. It’s just perfect. She accompanies herself absolutely perfectly.

BK: Personnel changes in your rhythm section are a rare occurrence. What inspires you to alter the chemistry from time to time?

TB: I’ve always had very superior musicians, like Joe LaBarbera and Paul Longosch, who were with me for many years. They’re perfect guys. Joe is the sanest person I’ve ever met, but he wanted to settle down. He bought a house and is working in L.A. and doing very well. He’s getting married. What happens is that after a while, certain guys get tired of the road. I’ve brought in some wonderful guys like Douglas Richeson from Ohio and Clayton Cameron, who played with Sammy Davis Jr. for seven years. All of the musicians say he’s the in thing right now. He’s everybody’s favourite drummer.

BK: Do you find travelling a strain?

TB: No. I’ve been doing it for 45 years and have gotten used to it. If you look around at people who live in one place, they feel strain, too. I love to read. When I get on an airplane, especially on overseas trips, I can finally get into some long-term reading. There are no phones. Other people say, “Oh, God, what a long flight.” To me, it’s like a dream. I can get into a book without having to pick up a telephone.

BK: Have you modified your style over the years?

TB: I think I have. You learn what to leave out. I keep trying to get better. I work at it and take good care of myself. I’ve done almost everything to experience life in the past, and now I feel very mellow about the fact I’m in control of myself. I’m disciplined, eating good food, and exercising properly. I’m 67 and in good spirits. I feel very good about life. I know that doesn’t make news, but I’ve never felt better.

BK: With all of the radical changes in popular music, you’ve managed to withstand the excesses, wear a smile and attract new fans. Were there periods that tested your confidence?

TB: Yes. Abby Mann, a good friend I grew up with and the author of Judgment at Nuremberg, said, “Do you realize how many producers we’ve been through, and we’re still here?” That was very astute.

Executives in record companies and other media, like television and film, feel very superior in their positions; but once they’re out of it, they have no power. Each new guy decides to change everything. Once the companies have enough of your catalogue, they get somebody else. If they sense you’re predictable, you’re out. To win the game of longevity, you have to bob and weave.

BK: When performing, where do you direct your art — to yourself, the audience or the musicians?

TB: First to myself. The whole idea is to communicate with the audience. I can’t wait to hit the stage. I’m that kind of performer. Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole, we all went for the audience. We want to entertain.

BK: Are you more at ease in concert or in the studio?

TB: I like all of it. You have to prepare for it. If you’re going to get nervous, it should be with a live performance because there are no retakes. With recording, you have at least four takes for every tune. You don’t have to release anything you don’t want to. With that many takes, you can usually find one that is near perfect.

With live performance, you’re going out there, and if that one shot isn’t right, it’s gone with the wind. If you’re going to get shaken up, it better be on stage, not in the recording studio. The studio feels comfortable to me.

BK: Do you ever fear they’ll release the outtakes on a compilation?

TB: They shouldn’t. It would be disastrous. I also paint, and one of my big jobs is to tear up the paintings that don’t work. You should never present a picture unless it’s absolutely excellent. And representative of you. You have to shoot for a very high level. That doesn’t happen every day. Most of the time, you’re just doing exercises in painting, and once in a while you hit one and say, “Look at that. It’s really good.”

BK: Have you always painted?

TB: I’ve gone to art schools my whole life. I’m still studying. I study with the best painter in America, Everett Raymond Kinstler. I feel so fortunate that he’s teaching me. Painting gives you a happy life. You’re studying nature. Every day you paint, you learn. You always feel fulfilled. It’s meditative and knocks out any of your worries. When you’re painting, four hours go like four minutes.

BK: Would you give me your brief thoughts or impressions on some artists? Sarah Vaughan.

TB: Sarah Vaughan was blessed with the most wonderful voice, a 4-octave range without falsetto. She was really the essence of a singer. When you say Sarah Vaughan, I say she was born to sing.

BK: Frank Sinatra?

TB: Sinatra is the king of the entertainment world. He’s conquered all the mediums. He’s the Al Jolson of today. He was also blessed with a golden voice.

BK: Billie Holiday?

TB: Every once in a while, very rare singers come along. I can think of three: Hank Williams down south, Edith Piaf in Paris and Billie Holiday. There is a destiny about those three singers. Their lives have become legendary.

BK: Joe Williams?

TB: A magnificent singer. He was with Basie’s band. I was the first white singer to sing with the band, and he was the vocalist at the time. Those were some of the greatest days, being around the Count Basie band in the ‘50s.

BK: Betty Carter?

TB: She’s a wonderful singer. You’re hitting on something that’s so interesting to me because when someone says to me what your category is, I find I dislike that word. I sing all kinds of songs, but I do lean towards pop-jazz singing. Like Ella, God goes through Betty on every note.

BK: Harry Connick, Jr.?

TB: I think he’s got a lot of talent. For a young guy, he’s come a long way. I had a lot to do with getting him into films. We had the same agent, and I suggested it right at the beginning. He’s just a grand guy.

BK: Which jazz artists do you listen to?

TB: I’m still bewildered by Duke Ellington. I think that he’s timeless and so avant-garde. Each guy in his legendary orchestra was an artist: Paul Gonsalves, Johnny Hodges, Harry Carney, Ray Nance, Cootie Williams. All these guys were part of an era of individualism. I love that era.

BK: With all the new reissues, artists like Ella Fitzgerald are topping the jazz charts with recordings that were classics in another era.

TB: That’s very good, you know. When there’s a change in the entire music scene, there are a lot of different reasons why it happens. The big thing has been the compact disc. All of a sudden everybody’s hearing recordings without any surface scratching. They’ll hear a production of an early Erroll Garner record and say, I never knew it sounded like that.

It’s an education for people who have never heard this on the radio. For 30 years, we’ve been rock-saturated. Young people have had to live through this obsolescent age, and they don’t know about great performers like Fats Waller, who made some magnificent records and is really fun to listen to. Folks in the Beatles generation now have two or three young children, and all of a sudden, they’re discovering their folks weren’t wrong. Young people are starting to come on board with artists like Natalie Cole and Harry Connick, Jr. In fact, I was even in Rolling Stone this week.