Honey Jam Celebrates 30th Anniversary

Fresh from being named to the Order of Canada, founder Ebonnie Rowe talks about the past, present and future of Canada’s first artist development program for female musicians. Honey Jam will celebrate with a special concert at Massey Hall in Toronto on July 30, 2025.

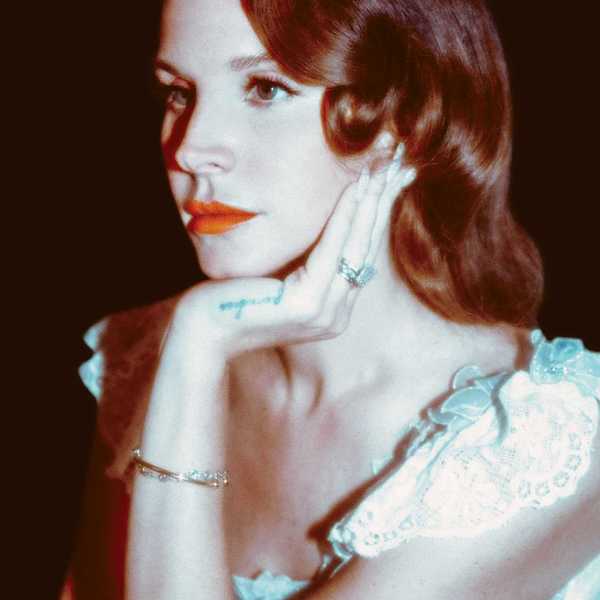

Ebonnie Rowe at Honey Jam's 30th anniversary mixer at The Mod Club in Toronto on June 30, 2025.

Ebonnie Rowe doesn’t turn down a challenge.

The founder of Honey Jam, Canada’s first artist development program for female musicians, has always faced the unknown head-on. When she founded Honey Jam in 1995, she was new to the music industry and facing an uphill battle in a landscape that was uninterested – at best – in supporting emerging female artists.

“This is not what I do,” she remembers thinking. “But there was no other platform for young women in hip-hop.”

Three decades later, Honey Jam is an enduring force in the Canadian scene, bringing in a new cohort of artists each year for professional development training and a major showcase opportunity at the end-of-program concert. Honey Jam alumni include Polaris Music Prize winner Haviah Mighty, multi-hyphenate icon Jully Black, rising star LU KALA and chart-topper Nelly Furtado.

Rowe will celebrate Honey Jam’s 30th anniversary with a concert at Massey Hall on July 30 (tickets available here). Titled Inspirations, the show marks the biggest venue Honey Jam has ever booked.

It’s a daunting room to fill, particularly in a climate of backlash against diversity, equity and inclusion, principles that drive Honey Jam. But Rowe is all about opening new doors.

“I’m a bulldozer,” she tells Billboard Canada. “I like to show up in places where no one would expect me, or the people around me, to be.”

This week, Rowe was recognized for her work with one of Canada’s biggest honours: the Order of Canada.

"She has been shaping the Canadian music industry for 30 years by supporting emerging female artists through her non-profit multicultural, multi-genre development program," the official citation states. "An esteemed mentor in her field, she provides artists with performance and educational opportunities, as well as a safe space to be vulnerable and build confidence."

It’s a recognition of Honey Jam’s history and impact to date, but Rowe is still looking ahead at what’s next.

The Seeds of Honey Jam

Honey Jam began with a mentorship program Rowe ran in the early ‘90s, Each One Teach One. Rowe had dropped out of university after a friend’s death. “Studying Chaucer and Shakespeare just did not seem important,” she recalls.

The program focused on at-risk Black youth, connecting them with Black professionals who might serve as inspiration. It meant that Rowe was spending a lot of time hanging out with teenagers, and she noticed they were picking up some attitudes from their favourite artists.

“Snoop Dogg had a line in one of his songs that said, ‘we don’t love them hoes,’” Rowe quotes. “It’s not popular to respect women. [It made it seem like] it’s not possible to be good to your girlfriend, that’s not the cool thing.”

She brought up the issue with DJ X, who hosted Power Move on Toronto community radio station CKLN, and he invited her to produce a whole show on the topic of sexism in hip-hop.

Rowe lives by a rule: “if someone gives you a platform and an opportunity, you take advantage of it or shut the f–k up.” So though she had no radio experience, she produced the show. Some were angry about it.

“It was the sacred all-male bastion of hip-hop,” she describes. “And who was I, this outsider? I had not asked permission.”

But the show caught the attention of Mic Check editor Jason Rosteing, a.k.a. Dr. Jay de Soca Prince, who invited her to edit an all-female issue of the hip-hop magazine. At the wrap party for the magazine’s launch, Rowe put on a concert – the first ever Honey Jam.

Honey Jam Reaches For the Stars

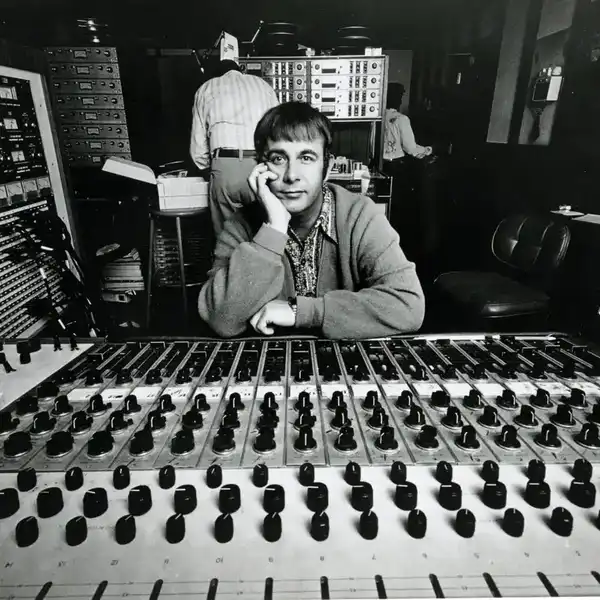

The program started off small the first few years, a passion project for Rowe as she worked as a legal assistant. Then in 1997, along came a young Portuguese-Canadian performer called Nelstar. She performed at that year’s showcase and caught the attention of her future manager Chris Smith and collaborator Gerald Eaton (a.k.a. Jarvis Church). Three years later, she would release her debut album as Nelly Furtado and catapult to international success.

“If it wasn’t for Honey Jam, I wouldn’t be where I am today,” Furtado said in a 2012 interview. When Drake brought her up on stage at OVO Fest’s 2022 All Canadian North Stars edition, which featured a slew of early 2000s Canadian luminaries, Furtado told the crowd: “it’s like Honey Jam all over again tonight!”

Rowe thought she might faint when she heard that.

Furtado’s career explosion helped Honey Jam in return. “We would have auditions where there might be 30 people,” Rowe recalls. “And then after Nelly Furtado there’s like a couple hundred people, where they’re lining around the block three hours before the auditions are going to start.”

In the 2000s, industry interest grew. Rowe cites support from FACTOR, the Harris Institute, and, especially Universal Music Canada, who provided resources to the program like a graphic designer and a street team for flyering.

As Honey Jam’s profile expanded in its first decade, so did its offerings. After the initial concert component was up and running, Rowe started to notice a pattern. Producers and “wannabe producers,” usually male, were approaching the artists with promises of stardom. Unused to the attention, many of them were wide-eyed and hopeful.

“There’s no internet, you cannot google these people to find out who is legit,” she remembers. “I was like ‘woah.’ They don’t know what they don’t know.”

That led to the professional development aspect of Honey Jam: workshops and panels that gave the artists tools to navigate an often predatory industry as young women. Initially, the teaching was led exclusively by women. Eventually, Rowe started to bring in men that the program could vet and trust. “I’m a big momma bear protector,” Rowe says.

That sharp instinct took Honey Jam to the next level. Showcasing concerts are key for any music career, but to actually thrive in the industry, artists – especially marginalized artists – need more than discovery or a deal. They need to know the industry.

Year-Round Opportunities

Growing up, Rowe had planned to be a teacher.

Though she’s not in the classroom everyday, it’s been a throughline in her work, from the mentorship program in the ‘90s to Honey Jam. Music wasn’t part of the plan, but it’s a natural fit with Rowe’s passion for justice. Rowe wants to lift up artists with something to say.

“I don’t have any children, so it feeds that part of me. The nurturing side of me. Victims for my nurturing,” she laughs.

The program has continued to evolve. Participants now meet role models in the industry during one-on-one ten minute sessions, what Honey Jam calls the Mentor Cafe.

Rowe’s favourite part of the program is the performance training, with vocal coach Elaine Overholt.

“If it’s a song that they’re supposed to be mad about, Elaine will stand right in front of them and be like, ‘ok so I am your ex-boyfriend that you found sleeping with your sister,’” Rowe describes. “It works, you know.”

More than the individual skills, Rowe notices that the program gives participants a sense of trust in themselves and the community around them. “You’re getting the knowledge, the nuts and the bolts, the opportunities, but greater than that is that support. And knowing that these people have your best interests at heart.”

Honey Jam doesn’t end after the final concert. Past participants stay connected to the Honey Jam community – actor Jordan Alexander, who starred in HBO’s Gossip Girl revival, returned to give a workshop and serve as an audition judge. Furtado was a financial sponsor for years.

The program also offers cohort members plenty of year-round opportunities. When Billboard Canada spoke with Rowe, she was fresh off a Black Excellence event with Adidas, which saw Honey Jam curate a performance from eight artists, marking a new partnership with the sports brand.

In 2020, Rowe even took a Honey Jam artist to the Grammys in L.A. That trip kicked off what was supposed to be a year of 25th anniversary celebrations, but COVID-19 had other plans.

Not to be deterred, they held Honey Jam online that year, live-streaming the concert.

The Future of Honey Jam

The 30th anniversary is posing a different kind of problem.

“I’ve been challenged to get excited about it,” Rowe says, “because I believe we’re in the apocalypse, with Trumpism that’s taken over the world.”

When she decided on Massey Hall for the anniversary concert a year ago, the world looked somewhat different. The new American administration is rolling back diversity, equity and inclusion policies and fuelling anti-social justice rhetoric against the kinds of work Rowe does.

“It’s trickled down,” Rowe says, noting that equity-driven organizations are seeing less enthusiasm in Canada too.

The only thing to do is keep moving.

“Figure out how to navigate the challenges, and let’s go. I need the artists to see us doing that.”

That perseverance is something Rowe tries to instill in Honey Jam participants.

“I tell artists, don’t do this unless you can’t not do it. You have to have that fire in your belly. There is so much disappointment,” she says. “You have to have the mental strength, the intestinal fortitude, the confidence, the desire, the passion, that you are going to push through no matter what.

“I have that for Honey Jam. I would do Honey Jam if I have a dollar in sponsorship or if I have $50,000 in sponsorship.

“Once I decide it’s happening, it’s happening.”

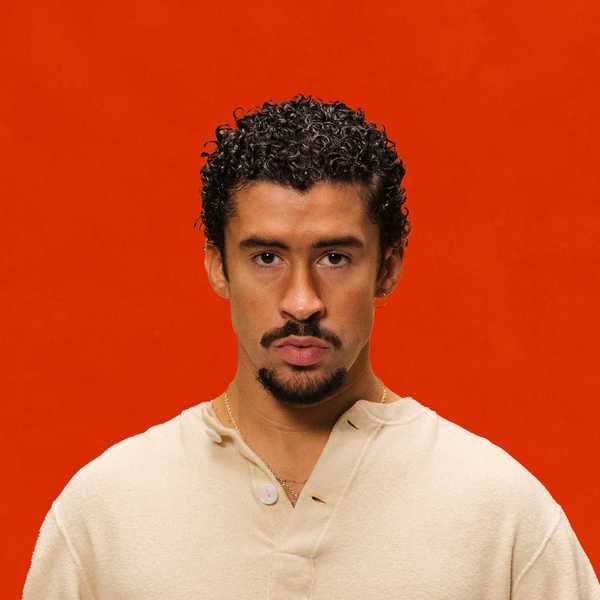

Simon GebrelulDiwang Valdez

Simon GebrelulDiwang Valdez Shai Gilgeous-AlexanderDiwang Valdez

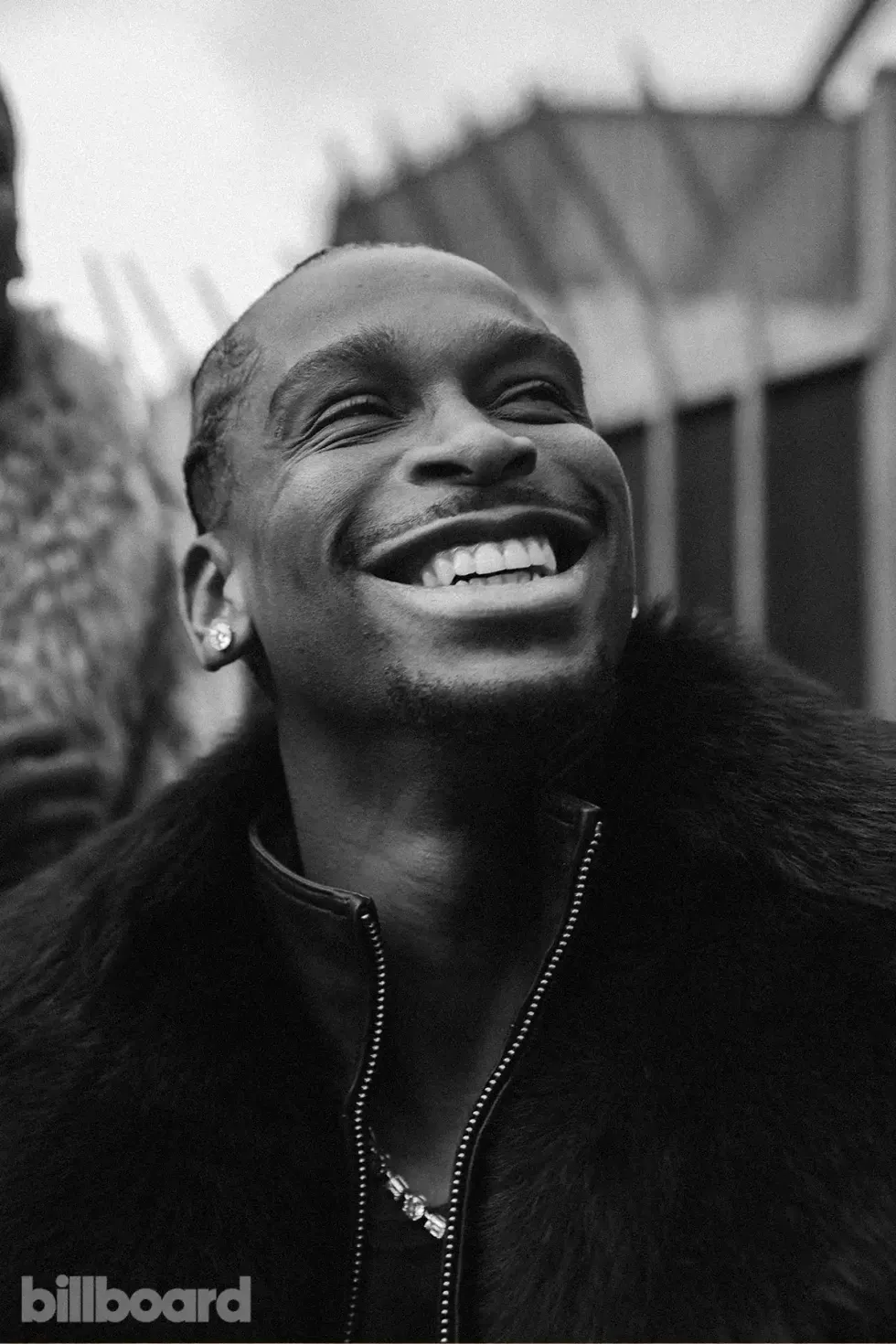

Shai Gilgeous-AlexanderDiwang Valdez GIVĒONDiwang Valdez

GIVĒONDiwang Valdez