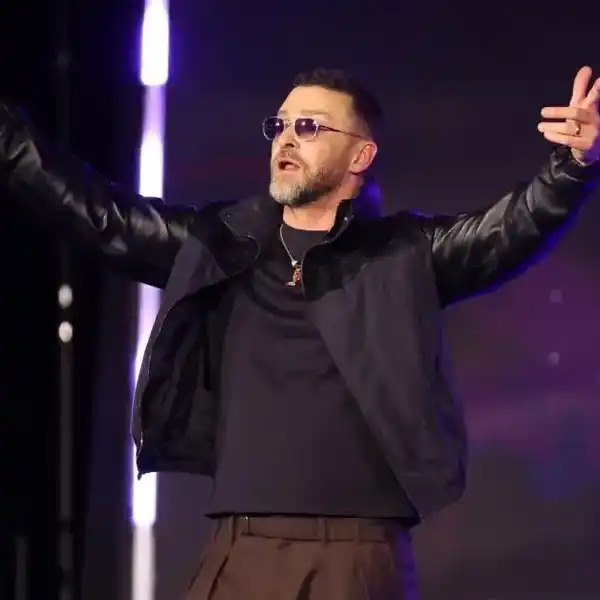

“I’ve Made a Heaven On Earth”: A Final Interview with Influential Canadian Music Journalist David Farrell

Shortly before he passed away, the founder of The Record, FYI Music News and editor at Billboard Canada sat down for a series of interviews looking back at his life and career.

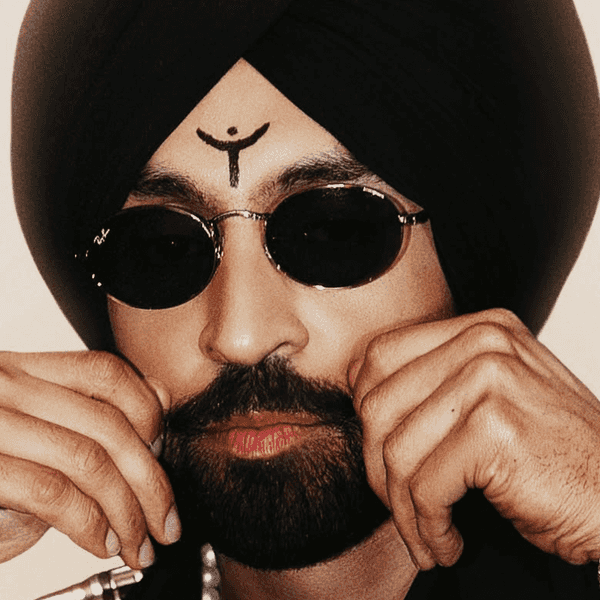

David Farrell

PARTNER CONTENT

This story is presented by Slaight Music.

David Farrell had a major impact on the Canadian music industry – through The Record, FYI Music News and the first authoritative music charts in the country.

But for all his trade writing, editing and publishing, including multiple stints as a Billboard editor, his voice rang through especially in conversation. He punctuated his declamations about the state of music or its institutions with off-colour jokes (often apologizing shortly after) and a dry English wit that cut to the heart of whatever point he was making.

Farrell died on Thursday (Dec. 19) at the age of 73. As Kerry Doole writes in his obituary, Farrell kept his condition quiet, sharing it only with a small circle of friends and confidants. However, he did graciously sit for a series of interviews from the home of his beloved partner Joan Ralph in New Brunswick where he spent his final weeks.

Perhaps in part due to his self-deprecating style, I wonder if Farrell got full credit for his influence on industry media, the charts and Canadian Music Week.

“Oh, I got lots and lots of credit,” he said.

But for all of his love of stories, he rarely wrote his own. That began to change over the last year as he won a Lifetime Achievement Award at Canadian Music Week and published a few reminiscences about people who influenced him, but he never wrote the book others suggested he should. And despite its name, The Record, it’s not easy to find copies of the magazine that chronicled the Canadian music industry of the ‘80s and ‘90s. So, he agreed to speak to Billboard Canada.

Farrell was born in Ladysmith, British Columbia in 1951 before moving to Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, England at a young age. As the British Invasion was taking over music and pop culture, he returned with his family in 1964 as a young teenager before studying journalism at Centennial College in Toronto following in the footsteps of his journalist parents Ann and Ted Farrell.

His first byline, he says, was in the Toronto Telegram, which he got through someone he met at the infamous student co-op Rochdale College. The story, naturally, was about a drug dealer. That led to articles about the big rock bands of the time: The Kinks, The Who, Genesis, Led Zeppelin, The Clash. Soon, he got typecast as a pop writer, when he really wanted to be a political writer.

“So now I was a pop writer, but there were 10,000 of them (there are less now),” he remembered. “We were all going to see King Crimson and writing down what we thought, and I started to realize this was kind of pointless – like really, who gives a f–k what I think about King Crimson? But I started to meet people backstage who all had fascinating stories, and their stories far eclipsed the stories of the artists. So I got beguiled by that.”

After a stint traveling and working as a sailor on trips from Fort Lauderdale, Florida to the Caribbean, Farrell returned to Canada again and became a syndicated music writer – first for the Canadian Press and then, soon, selling directly to newspapers. In 1975, after turning down a job offer with the Barrie Examiner, Farrell was hired by Joey Cee to help set up a Canadian music industry weekly called Record Week. In 1976, Farrell became Canadian editor of the American trade magazine Cashbox and then the Texas-based magazine Performance.

Soon, he became a Canadian editor for the leading music industry trade Billboard, where he worked from 1977 to 1981. There, he honed his interests that would later lead to his own projects within Canada.

“Once a year, I had to write the Canadian Billboard report,” he said. “It was about 10,000 words, and you covered all the beats: live music, publishing, labels. You had to go and interview all the record company bosses, and you’d walk out thinking you had a good story, but when you listened to the tape at the end of it, you realized that they said absolutely nothing.”

At Billboard, he started writing about Canadian success stories that he would follow throughout the rest of his career – bands like Chilliwack, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Bryan Adams, Loverboy and Platinum Blonde. But he maintained the opinion that the more interesting stories were happening behind the scenes.

One of his beats then was reporting on “white collar criminals” who would counterfeit and import bootlegged records into Canada and the United States.

Farrell and his then-wife Patricia Dunn had moved into an old priest’s mance in Horning's Mills, Ontario, where he had his first son D’Arcy (they had two more sons Brendan and Lewis). One day, he said, he got a threatening call to his house from someone saying they knew who he was, they knew he had children and to stop writing about bootlegged records.

Farrell recalled that – in a moment of exasperation – one Billboard editor told him that, in its the magazine’s then-century of history, he had been sued more than any other writer.

“They were all frivolous lawsuits, but it became rather frightening because anyone with any money could sue you,” he said. “They could end up costing me $5,000, which as a freelancer was a lot of dough.”

While in Horning’s Mills, the workers at the Canadian trade RPM (which helped found the Juno Awards) went on strike, and Farrell spotted an opportunity. He drove to Toronto and went to the heads of the big record labels – then A&M, Warner, CBS, Capitol, RCA, Polydor and MCA – and said he would start a newsletter if they would split the costs.

Everyone agreed except one person: Doug Chappell, an executive at A&M.

“He said, no f–cking way. Nobody wants to read your bullsh-t,” Farrell recounted. “What they want is facts. This industry is starved for facts.”

That philosophy begat The Record, which started in 1981. Farrell remembered collating and stapling pages himself along with Dunn, his co-founder, and later, when Canada Post went on strike, personally driving it to the record labels to drop-ship it to their radio and sales hubs across the country.

In those early days, in 1982, The Record began a conference called The Record Conference, which eventually transformed into Canadian Music Week. Farrell brought on Neill Dixon, who helped organize and choose the speakers. “And they actually said stuff on stage,” Farrell said. “They didn’t just go up and go ‘blah blah blah blah’.”

There was also a musical component at The Bamboo club on Queen West, he remembered, including an early show by Blue Rodeo. In later years, he sold the festival to Dixon, who retired last year and sold the festival to Loft Entertainment and Oak View Group, who have since renamed it Departure.

Farrell was still writing for Billboard when The Record started. He said he had a secret handshake deal with his New York editor that he could keep doing both as long as Billboard would still get first run at stories. After about a year, his work at The Record did start interfering, so he devoted himself fully to his own publication.

At first, he said, it was light on editorial but heavy on facts and data. They sourced a list of AM and FM radio stations and retailers in major and secondary markets and requested their weekly top 10s and started developing a chart system. The Record’s charts for singles and albums became the benchmark domestically and internationally for what was going on musically in Canada. They were also printed by Billboard.

At the time, this information was all collected manually and The Record had multiple dedicated people to do it. Eventually, as accounts were added, it became unwieldy. The Farrells flew to New York for a meeting with Billboard’s charts editors, Tommy Noonan and Marty Bender, to come up with a solution.

What followed was a licensing deal which used Billboard’s technology (which Farrell said was declassified spy equipment from the American government) and data. Soon, The Record developed a reputation as the Billboard of Canada.

“It was our charts and we published them, and it had the credibility of the Billboard chart system,” he said.

Eventually, though, Billboard began printing their own Canadian charts, Farrell said. That, along with a decline in advertising from the record labels in the age of consolidation “when they all started cannibalizing each other” led to hard times for The Record. Farrell sold the magazine to early online streamer MusicMusicMusic, and then it folded in 2001.

Farrell, then divorced, moved to Nova Scotia “basically unemployable” to try to start over in a new career. His youngest son convinced him to come back to Toronto, which led to him meeting the people behind online distributor Yangaroo. “They gave me a little bit of technology and an office,” Farrell said. “And I started working on a new music industry trade.”

What would become FYI Music News truly got going in 2008 with full-time funding from music mogul Gary Slaight, who loved the idea of a music industry trade newsletter. FYI became a resource for the music industry, with many of the top execs subscribing and reading it religiously.

Things came full circle for Farrell last year, in 2023, when Billboard Canada acquired FYI. Farrell came over in the deal to continue his work on the industry newsletter, becoming a Billboard editor once again for the first time in decades.

“Derrick [Ross, President of Slaight Music] told me someone was interested in buying FYI, and he said it was Billboard,” Farrell said. “I said ‘what the f–k, they put me out of business!’ It took me awhile to assimilate that, but once it started, it was fantastic. [Billboard] left me at the back door, and now here they are at the front door, a cheery new bunch of people who don't remember any of the history, saying ‘let's make a deal.’”

Farrell looked back fondly on his time covering the Canadian music industry, and pointed to the rise of figures like manager Bruce Allen and companies like Live Nation, which were born in Canada and went to become some of the most dominant forces in music. “Those were some real characters who built infrastructure and changed the industry on a worldwide scale,” he said.

Speaking in 2024, he was not as optimistic. He said record companies are too reliant on government funding, and creative thinking was snuffed out by taking too much stock in social media and stream counts.

“Where is the music business anyway?” he said. ”It's just a bunch of people sitting there looking at charts fed to them by TikTok. You used to have to go out and hear some bands at different clubs, sign bands, develop them, put some money into them, put them on our tour, subsidize them for that tour, and then take them to the next rung. That doesn't exist anymore. The whole thing is synthesized, and the person they put out there might last only three singles. It's not the music business, it's the technology business.”

His career wasn’t always perfect, he said, and would sometimes tell me about times he might have been fired. But, in his final days living in the picturesque Shediac Bridge, New Brunswick, where he moved during the pandemic, Farrell said he was happy.

“I’m a lapsed Catholic,” he told me. “I believe we make our own heaven and hell on earth, and I’ve made a heaven. And if, later on, if I end up somewhere else, I’ll just look up and say ‘f–k him’!”

Read a full obituary of David Farrell featuring tributes from his friends and family here.