Media Beat: My Life In News

Libel, liquor and good times from a cub reporter through to today.

My first job as a writer in a newsroom was memorable. This was 50 years ago when alcoholism was rampant. The lockers for topcoats and winter boots were unassigned, and, more than not, they were littered with whisky and vodka bottles. Crown Royal was the most popular. Dinner was across the road in a pub where many of the writers, myself included, dashed in to down a couple of meat pies, and a couple of beers which then cost one all of 20 cents for a regulation draft-sized glass.

One evening, on my return, there was a loud thud, and I swivelled in my chair to see one of the teletype operators, who, it turned out, was dead from a massive heart attack and sprawled out on the floor below his machine. I swivelled some more to the news editor, a long-standing veteran who could proof and copy edit in any condition. On this evening, all I could see were his hands moving across his desk, looking for more copy or an editing pencil. He was on the floor and certainly quite pickled.

The environment for a young buck was toxic, and several days later, I shared my thoughts with the GM, who worked on a different floor in a cubicle-sized office with one of those heavy metal, government-issue green desks. It was around 10 in the morning. He listened to what I had to say and then quite surprised me by reaching over and pulling out a bottle of Scotch from a drawer, to ask if I wanted a drink. I quit shortly thereafter.

If it all now seems outlandish, unreal and beyond the pale, it was — but it wasn’t uncommon.

Back then, newsrooms were wildly populated by talented newspeople, mostly men, who lived large and had memories like elephants. I started early as a copy clerk at The Globe and Mail. The rim, which consisted of two half circles, had the editors, headline writers and the copy editors and behind them a bank of journalists who took late-breaking stories (concert reviews, sports summaries) over the phone. The reporters on the scene perhaps had some roughly scribbled notes, but many just had their stories filed in their minds and filed from a payphone from wherever they were.

The Globe was an interesting place to work. At the time, we had columnist Richard Needham, who worked from a grungy office at the back of the newsroom. His published stories in the day were hilarious, but for us copy clerks, grunts who ripped news stories from the teleprinters to be rushed to the various departments, Needham’s magic was the seemingly unending parade of glamorous, youthful, and beautiful women who came to see him almost daily.

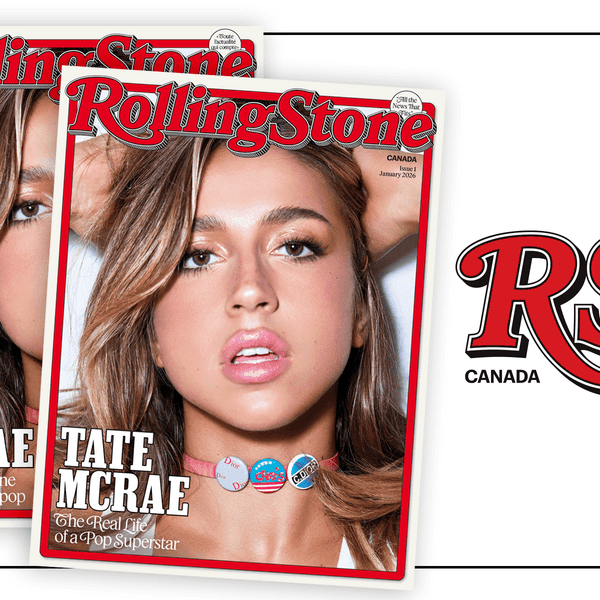

Ritchie Yorke was in the entertainment department. One of the few salaried rock reporters with a daily in North America. He was something to see, ever always with a wine-tipped cigarillo, often dressed in cherry-coloured crushed velvet bellbottom pants and perhaps a purple satin shirt, complemented with a smart pair of Cuban-heeled boots. Daily, boxes of LPs would arrive for him from Motown in Detroit, couriered packages from glamorous places like Los Angeles and New York. We did his bidding, which in most cases required us to photocopy massive feature stories he had written about Aretha, Muscle Shoals, John and Yoko. Whatever his job at the Globe was, it allowed him to syndicate to newspapers abroad and to Rolling Stone, where he was regularly published. In return for the off-the-book photocopying, we received albums and sometimes concert tickets.

He was a loveable rascal.

One of the newbies reporting at the time was Michael Enright, who would often arrive wearing a deer hunting hat with a matching tweed cape. He was elegant and clearly living the part of a reporter from another era, but he had a nose for an angle and could spin a story as well as the best.

And then there was Dick Beddoes in Sports. Forever wearing a hat, quiet and ever undemanding. Almost daily he would receive a full Canada Post sack of mail from readers; some irate over his opinions, others blessing him for his knowledgeable insights. The departmental secretary, Lynda, I think her name was, dutifully punched out a response to each, which Dick signed. They all read Name…' you may well be right' — and every one personally signed by Dick Beddoes.

At the CBC, working on the fifth floor of the Jarvis Street headquarters in Toronto, Trina McQueen reined as one of the few women who had shattered the glass ceiling back then. She ran the national newsroom with aplomb and never seemed to be unnerved by the rush to deadline daily. She was quite remarkable, as was Ann Medina, an American TV journalist with impeccable credentials and a hard nose for getting at the truth of a story.

And then there was Larry Stout who went on to join CBS’s Newsmagazine. He was a no-nonsense but affable type who worked hard and expected others to match him. One day I came onto the floor to find Larry driving his fist into a cinderblock wall. It turned out he had reported on a story from somewhere in the city and later sent a camera operator to shoot backgrounder footage from whatever he was reporting on. We were on deadline, and it turned out he had not specified that the camera operator put film in the camera. The union protected the camera person because the instruction was imprecise, and that was that. The unions at the CBC then, and probably even more so now, were a power unto themselves. It’s no accident that the standalone converted mansion on the CBC premises where the brass was housed was called ‘The Kremlin.’ Strata and power existed in every nook and cranny of the complex, but somehow, the news was reported on, and Knowlton Nash managed his cheery smile each night.

Working as a Canadian correspondent for Billboard later, one of my weekly perches was a drab provincial office building where records of lawsuits were filed. I would thumb through the pages of oversized books looking for anything that could be an entertainment lead. I found a few, but my overarching memory was the sheer number of lawsuits filed against the CBC. The Crown’s lawyers must have been overworked. I’m sure they weren’t overpaid. And many of those legal actions, I’m equally sure, were frivolous. People and companies with money rarely like the truth to be told, especially so when it involves them.

Libel suits? I have had a few. Most frivolous and unfounded, but one story that had me quite nervous was a lengthy interview I had done with Malcolm McLaren, former manager of the Sex Pistols and a punk culture prince. The interview started with the moistest handshake I’ve ever had, but he was a marvellous raconteur, and his stories just piled one after another that were all scandalous, often salacious, and he was brazen about naming names. At the time, I was running The Record, and my sixth sense told me I had to run this one by a lawyer who specialized in libel. For a few hundred dollars, the answer came back. 'Unprintable' unless you are inviting trouble.

I’ve never read anything quite like the interview he gave me, except superstar Brit music manager Simon Napier-Bell’s tell-all book, Black Vinyl, White Powder. I guess his stature, wealth, and precise, detailed accounts saved his bacon.

Another couple of stories from The Record era (1981-2021) had me attending the New Music Seminar in NYC. It was what Canadian Music Week became. Between sessions, I was in the cavernous lobby bar area. One of the most powerful indie record promoters in the U.S., a fearsome character who always delivered, must have been told I was nearby and operated radio charts in Canada. He approached me and asked if these charts were “transparent.” At least, I think that is the word he used. Whatever he said, I knew his intent. When I said ‘yes,’ he lost all interest and went back to his mob at a table.

I’m not sure if it was that particular conference or one at a later date, but it was after 1 a.m., and I was standing outside the hotel with Stuart Raven-Hill and perhaps Brad Roberts from the Crash Test Dummies. Joining us were Cowboy Junkies' Margo Timmins, Jeff Rogers and Graham Henderson. It was Margo’s birthday, so, already well watered from attending showcases around town, we all piled into The Russian Tea Room around the corner from the hotel, where we laughed and talked and continued drinking, but this time downing Russian flavoured vodkas neat. The real stuff. Not the pretend Russian vodkas one can readily buy today. I remember having several, the last of which was infused with garlic. To this day, I have never forgotten the morning after the night before, and still have a lingering dislike for garlic.

And, of course, there have been gigantic blunders. Perhaps the biggest and most obvious was with the first edition of Record Week, the Joey Cee self-funded weekly music trade that was supposed to unseat RPM in the mid-1970s. The copy for the first edition was scrupulously proofed by myself, Martin Melhuish, Larry LeBlanc, and perhaps Juan Rodriguez — all involved in that short-lived weekly newspaper. Well, off it went to the printer, and there, on the front page, as the lead story, was an article about some new outdoor arena that CPI was controlling. Instead of calling it a new concert site, it was spelled ‘concert sight.’

Groan!

Several years later, Record Week celebrated some sort of anniversary, and we took ads congratulating ourselves on a job well done. Don’t you know it, Robert Charles-Dunne and Joe Owens, then running a music entertainment PR firm, took out a quarter-page ad congratulating “Record Weak.” It was intentional. It was fun, and we caught it.