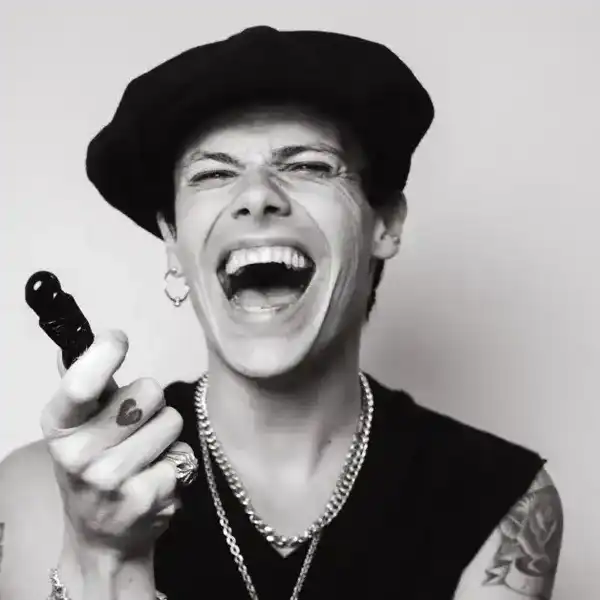

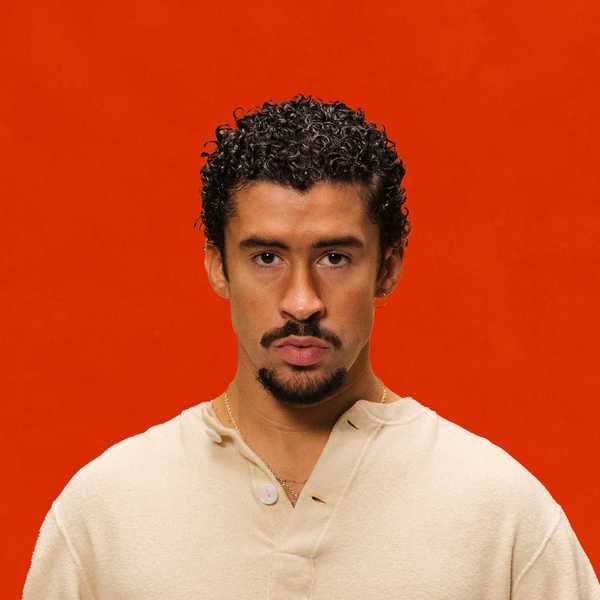

A Conversation With .. Kurt Swinghammer

This creative renaissance man excels as a visual artist, musician, and singer/songwriter. In this far-reaching chat, he discusses his artistic approach, parenthood, Maestro Fresh-Wes, the Queen Street West scene, a fascination with Pierre Trudeau's love life, and much more.

By Bill King

Kurt Swinghammer has left a lasting mark on the Toronto music and art scene – the once berated yet always forward-thinking city. The ‘80s were a time of grand possibilities – the MTV/MuchMusic generation – art with no borders. Kurt was there – influential and painted our minds with eye-popping colours and jagged brushstrokes.

Bill King: We met in Newcastle, Ontario in 1970?

Kurt Swinghammer: Yeah, that's where I first became aware of you. I think I met you very briefly.

B.K: You were how old then?

K.S: I would have been like thirteen, fourteen.

B.K: Your dad was the chief of police?

K.S: He was the head honcho.

B.K: Mary Lou?

K.S: She was my sister. You were in that band Homestead and they were the first rock people that I knew or had any connection to at all. I had your poster on my wall. It was a huge deal to see freaky guys with long hair that played instruments. That's what I aspired to be.

B.K: We spent four or five months on Bobby Orr’s farm. We rented from him through an agent for about $200 a month. The idea was for the band to come together and sort things out, write material and get creative - but it turned into a “psycho” show when the drummer lost it. I still have this image from down in the police station with your dad and him interrogating and the drummer, eyes bulging – lecturing him about vegetables, and a lot of weird stuff. Your dad comes out shaking his head.

I also think about the fact that it was a great area. One side of the farm was an 80-acre orchard of apples, the other, three hundred acres of corn. It’s all sub-divisions now. It had to be absolute magic growing up there.

K.S: I was there only a few years. As an O.P.P officer, every time my dad got a transfer, or a promotion, he would be relocated, so we bounced around a lot of small towns. I was starting to learn how to play guitar and getting serious with visual art. That was also the era of bands playing high school dances - that kind of golden age. I saw Mainline (McKenna/Mendelson) play our high school. It's hard to imagine now, but I don't know if they were on smack or what, it was like they sat down like old blues guys and played, and everybody was confused. I ran out and bought their records and became a substantial Mainline fan because of that.

B.K: You had to be a fan of David Andolf’s cover art.

K.S: Oh, yeah. I copied his stuff diligently and learned a lot. He was a big influence - also adopting Canadian iconography for their images - as a young kid you're searching for your identity. I have reached out to David on Facebook and said, “Hey, man, you know, like you are a big inspiration.” I've met Mendelson Joe a couple of times and recorded him once but he's such a curmudgeon, it'd probably have been better not to have met him.

B.K: What was it artistically? What were you seeing? You had a style that captured the ‘80s and permeated Toronto?

K.S: I was lucky to get asked to do things like volunteering to do imagery for CKLN radio which was a pretty vital station in the ‘80s. I donated the work and was happy to do that. And in compensation, I'd get tickets sometimes to catch shows, and some of that stuff did get out there, like fundraising T-shirts and things.

B.K: I was impressed with your work for the Shuffle Demons.

K.S: I did their wardrobe and album covers and videos and items and it did well locally. There's just a number of these things. And then the Maestro Fresh-Wes videos blew up. He was this unknown rapper and suddenly won Juno Awards and all that for these videos and that opened up a lot of opportunities.

The work I was doing at that time was kind of in response to what I thought in the commercial world was very stiff and very dull. I wanted to liven it up. People were throwing around this term “neo-primitive” at the time because it was discarding some technical stuff that tended to make things look boring. I was just trying to create work that was vital and fun and expressive.

B.K: To me, the influence seemed to be Africa.

K.S: Folk arts from all over. Including, First Nations stuff. When I was a kid growing up all of that was so attractive to me and these days you have to be careful how you use it because you seem to offend people very quickly. But at the time, I just loved it and I equally loved The Flintstones and cartoons and stuff - it all meshed together. Mainly, it was a retaliation against an icy corporate world. On the street level, it made sense to do something that was like that.

B.K: What were your tools?

K.S: Animal hair at the end of a stick with some gray pigment?

B.K: Did you buy your first paint kit or was it your parents?

K.S: When I was very young, I was drawn to making art and even before going to school, I could tell people were encouraging and impressed with the stuff I did as a little kid. We always had paper. We still had paints. My mum had a bit of an interest in painting herself. It seemed I had a natural affinity towards making stuff.

B.K: The father's a straight-up policeman, a cop and the son is in the arts. Was there conflict?

K.S: There wasn't a lot of support, right. We didn't have much of a relationship and rarely talked. He was not a very present dad. I’ve tried to analyze it, to figure out why I followed the path I did. I think part of it was because my dad wasn't there for me. I became introverted and music and art was something where you just shut the door and do on your own. I think that’s why I turned there and that allowed me to sort of make sense of the world.

B.K: In later years did he ever comment on the body of work?

K.S: I was fortunate to get a fair amount of press for a stretch – the Toronto Star and I would get on TV. I know my dad was very proud of that. He would brag about it with his friends but on a one to one level, he could never say much else.

I have a six-year-old son now and I was kind of nervous about reiterating some of the stuff that my dad did, but I think I'm mindful of it. I'm trying to be naturally very supportive and encouraging of my son. I’m astonished to believe that people can have kids and then ignore them and think about themselves or not have a natural affinity towards being a great parent. That just kind of blows my mind.

My son’s first interest in music was marching bands, which was kind of like the last type of music I ever considered. There's the military aspect of it. He was obsessed with the Ohio State Marching Band and I started watching the videos with him when he was three and I could see, what a spectacle. There are 200 people on there - like twenty sousaphones and they're creating these geometric formations on the field. And I thought, no kidding - this beats a rock band in sheer spectacle.

B.K: The music came from where?

K.S: Early on, singer-songwriters were speaking to me. Joni Mitchell and Neil Young, but also Burt Bacharach - my ear was excited by the world he created. Even though it was intended for adults more, his work has stayed with me. It’s been a constant I keep going back to and a perfect balance of sophistication and humour and creating a very personal sonic universe like in breaking bars apart and not being predictable. You’ve got to have a chord chart if you’re going to play. Joni Mitchell’s songs have also been an inspiration. As time went on, I got into Brian Eno and his electronic adventures and Steve Reich. There have been countless sources of inspiration, but early on, those were the main ones.

B.K: Every songwriter needs somebody of equal talent or abilities that fits the song to deliver it in a shape imagined?

K.S: I love it when Bacharach sings. He doesn't very often. It’s a meek voice in a way, but to me, it's so expressive and in his live shows he would do Alfie himself. That to me was always the highlight of the show because he's so vulnerable and honest. At one point he and Dionne Warwick broke up and he would have these good singers, but they were to me generic sounding, but his voice is so close to the song.

B.K: Are you satisfied where you are musically?

K.S: It's always evolving. It doesn't stay in one place. I've never felt like there’s a real plateau or a rut.

In the mid-‘80s, I started putting out independent cassettes, and would maybe sell three hundred at gigs. They were quirky, kind of humorous things, home recordings on a four-track tape. I was thinking this is like a bake sale, yard sale type of thing. I'm just making my stuff. I sent some to record companies, but there's never, ever any interest.

They were unusual, weird, quirky songs in that they progressed and at one point I was able to go into a 24-track studio self-realized, self-financed and then put out a dozen solo records - all my writing and my singing and guitar playing, and everyone has got its own identity. Sometimes there's a thematic element that binds things together lyrically. They are like song cycles or concept albums.

That's been something I've been pursuing the last number of releases - try to make a cohesive statement and go beyond just writing one song - write forty-eight minutes of music about one subject. I think the first one of that ilk that I feel was my most robust realization was this song cycle called Vostok 6, about Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. For every song, there is a musical theme and all the lyrics connect. It's a metaphor and serves my purpose, my personal needs to write songs about my life. I tried to make it universally that it could be about something else and other people could relate.

B.K: And you're an avid reader?

K.S: Not a whole lot. I should be.

B.K: I’m guessing those invested in creativity usually have an abundance of ideas to sort through and consider?

K.S: There are times when I’m incredibly absorbed in books. I wanted to read more and have a Kindle when that technology came about. I was reading more because you could take it to the dentist's office and read. When I do read, I tend to read bios - Quincy Jones's bio or whatever. The most fascinating thing is to learn about someone's life.

B.K: Any that stand out for you?

K.S: The one on Marvin Gaye by David Ritz - he's also written a great one on Jimmy Scott. Curtis Mayfield, written by his son. I was just enamoured with Curtis's music. Then to find out years later, the story behind it just kind of dismantled the romanticism of it, but it was fascinating to learn his story - shocking.

B.K: What was shocking about it?

K.S: There's this beautiful story of someone coming from absolutely nothing - like extreme poverty. Rising above that and finding a way in and then becoming one of the most successful artists of the time, creating his label and studios and all that, and then ending up behind a locked door doing a lot of cocaine.

The son lost his dad to that before a tragic accident on stage. To hear it from the son's perspective was kind of shocking that someone that prolific and that great could end up not being able to deal with success or the money or fame. It's an impressive arc of a life.

B.K: In the world we inhabit, there are many avenues. You’ve picked yours.

K.S: I like to work. That's something that's always been a constant. I want to be productive. That's what I get off on the most.

B.K: The rise of your career as an artist paralleled the arc of Queen Street, the BamBoo and everything going on during the ‘80s and ‘90s in Toronto. When we look back historically and as we recall the bands of the day, we will always see your work. Do you give much thought to the times?

K.S: It felt natural, the places I played and the places I hung out; the Rivoli and the Cameron were just a natural fit. I felt like that was my community and even MuchMusic you could access. You couldn't get on most TV and they would play your video or have you in for an interview and now it's just such a different world. They don't respond to the local community the way they used to.

B.K: CITY TV’s Lance Chilton was on-site at six o'clock at either The BamBoo, The Rex, The Rivoli, or another jazz club. It was that “live hit” from a club that made a difference.

K.S: They were very supportive. And at one point I was doing a lot gigging. I was writing themes for some of the shows - Media Television was on for 13 years and the theme music was a bit of a calling card for me. They gave me a bunch of opportunities - even the video awards, I did the music and design for one year. Joni Mitchell, when she did the intimate and interactive, I did the set design. At one point it was so accessible, and you felt this is my city, my community and we have an outlet here with this media. Things have shifted. There's different technology now that means you can make your broadcast, everything. But at that time, it felt comfortable and natural.

B.K: Do you sell your art through galleries?

K.S: Yes.

B.K: Stylistically, a lot has changed.

K.S: Like most people, there’s a fair amount of diversity in the work. I am doing work now that doesn't connect to the illustrative stuff I became known for back then. It's work that has evolved and it satisfies my need to create and people like it. I still do messy things. The new work I'm doing right now, there's a show opening this weekend. It’s wood sculptures that you put on the wall. That's a new thing. It's essential to keep on pushing and trying to find something new to say and exploring. When you're a kid, half the excitement is, 'I've never done this before.' That's a type of feeling I try to tap into to this day. It’s the newness, like hearing the Beatles for the first time. If they sounded like everything else you heard, no one would care. It was that newness that everybody got excited.

B.K: Do you follow the art world outside of your work?

K.S: A little bit. I’ve got a membership to the AGO and stuff, but I don't haunt galleries or I don't have a need to hang out at openings, but I certainly appreciate seeing great work.

B.K: ‘Group of Seven.’ Any thoughts?

K.S: One project I did is a music song cycle called Turpentine Wind and that’s a meditation on Tom Thomson's life. The very first time I ever set foot in an art gallery was the AGO and they had a Thomson retrospective and I may have been fourteen or fifteen. I made a pilgrimage there and it really made a huge impression and always really connected with that work. The album Turpentine Wind uses his life as a sort of a mirror of my own. Like every artist, you must find a way to make a living and Thomson had some patrons, but he also did a lot of commercial work, which people don't factor into his life. He did illustrations and window designs and things like that - whatever gig you could get. That's every artist, you often do commercial work. I was using his life as a sort of example of how to find a balance between those two realms.

B.K: What's up now? Is there something in your head that needs to get out?

K.S: I always have a body of work that I am planning to get at. Musically, I've got a new album in the can and it's mixed and will be releasing very shortly. It’s a song cycle about Pierre Trudeau and his relationship with Liona Boyd and Barbra Streisand.

I was just always fascinated with that. Musically, it's all nylon string guitar with some trumpet and some electronics. It's taking a sound in a way and using it as the basis for this. Design during that era – Canada was on the leading edge. I’m using Trudeau to represent that kind of optimism and idealism as opposed to critiquing his politics. This complicated romantic relationship he had is a reflection of something that I was going through. This tradition of the singer-songwriter is to be autobiographical. I don't want to make it so that it's so personal no one else can feel they can enter that. I’m trying to find these metaphors that work.