Marley, Massey Hall & the Kings!

The music of the king of reggae, on full display at a legendary show at Massey Hall, had a huge impact on Bill King, and, later, upon his son, Juno-winning producer Jesse 'Dubmatix' King.

By Bill King

Over the past forty-four years, I’ve stored in a garage or basement and transported fifteen 2” tape recordings, most absent track sheets, and recorded between 1974 to 1985. Some were jazz tracks, and others, reggae and funk sessions with my various bands.

Out of curiosity, I had four baked - the stems retrieved and sent to Dub Arc Studio, owned by Jesse “Dubmatix” King. Within these grooves are players such as bassist Harvey Brooks of Bob Dylan and the Electric Flag fame, Everton Paul and Wayne McGhie – Reggae Hall of Fame honorees, jazzman Pat LaBarbera of Buddy Rich and Elvin Jones fame and brother Joe – long-time drummer for Tony Bennett and a celebrated cast of music luminaries. Both Jesse and I were thrilled at what we heard. These are tracks with a timeless quality that capture the spirit and cross-cultural curiosity of the musicians involved. Players without borders!

It was 1973, and Toronto was undergoing a cultural shift. The usual pop fare was starting to assimilate the rhythms of the Caribbean – not just soca, and calypso – but a music known and beloved by those who immigrated from Jamaica called, ‘reggae.’

With the addition of Trinidadian bassist George Phillip, reggae soon became part of the King family landscape. Along with being a superb musician, George came loaded with ‘45s – those antiquated singles that made every DJ on the planet a ‘go-to’ music curator.

George collected nearly every current recording coming out of Kingston, Jamaica and made sure I had a listen. At first, I couldn’t get past the monotone singing of the dub artists; the dry cadence and deep slap-back echo and reverb. I honestly thought someone screwed up the mix, but George assured me the music was revolutionary and there were bands about to bust wide open, particularly the Wailers, who had something far different to offer.

As time passes, I become intrigued by the bass patterns and exotic rhythms and begin incorporating them into my music. I recorded a second album, Dixie Peach for Capitol Records and the process of bringing those flavours and rhythms to a variety of composition became imperative. George and I shared a good many rehearsals with drummer Pentti “Whitey” Glan and guitarist Jake Thomas and tried to incorporate the new sounds within the unit.

George recognized I was embracing the music and invited me to come along and check out a rhythm section he said would ‘turn my head around.’ Secondly, he told me they had a great lead singer/guitarist and drummer who also played exquisite soul music.

We gather at the old Masonic Temple at Davenport and Yonge near starting time. I would learn there was no such thing as a ‘calendar’ starting time; only Jamaican time.

We observed a DJ play an endless stack of dub ‘45s and then the call for refreshments went out, and a few dreads gather in the stairwell. I’m there with my neighbour Jerry Rogero, who quickly adapts to the change of scene. “They’ve got weed man,” he says in a celebratory tone. “Let’s get in there!”.

We spot a group of dreadlock men clamouring for rolling papers. Weed arrives but nothing to roll it in. A day-old newspaper is found, and all was made right. The newsprint was then rolled and shaped into a spliff and then sticks, leaves and seeds stuffed down the funnel. The resulting joint was at least ten inches long. Then came the lighting of the torch. After witnessing the stand-alone moment and the ensuing slow drags and long puffs, a classic country song came to mind – “Don’t Bogart That Joint!” written by the Fraternity of Men.

A follow-up song was composed later that night, ‘Don’t Part with That Joint My Friend.’ By the time the spliff makes the rounds and lands near us, it had dwindled to the size of a classified ad. I was cool with this, but not pal Jerry Rogero who closely monitored as the joint diminished in size and passed slowly through hands. Jerry would shake his head, mumble something, then roll his eyes in disapproval.

Keyboardist Jackie Mittoo was a legend in Jamaican music circles. On this occasion, the main attraction, except there was no audience. The band played anyway. One never knows if these events are advertised or arranged absent a plan.

Mittoo was at the centre of the band playing the organ with Everton ‘Pablo’ Paul drums, Wilfred “Wayne” McGhie, guitar and vocals, and George Philip, bass. The band tore it up. Paul played solid roots reggae with plenty pop in the drums and a relentless groove. McGhie played rhythm guitar with great authority and sang in a soulful, raspy tenor much akin to the deep southern soul singers of my generation.

That night, I stole Mittoo’s band!

Toronto has had a long storied history with reggae dating back to the early sixties. Wayne McGhie just happened to be one of the first expatriates to record ‘roots music’ in Canada, far from the Caribbean Sea. The music was mostly heard in social clubs and after-hours joints away from the white music rooms that dotted the midtown landscape.

The first Canadian Jamaicans were slaves imported to New France and Nova Scotia in 1796. In 1955 Canada introduced the West Domestic Scheme making it possible for young women 18 – 35 enter Canada from Jamaica and Barbados in good health, with a minimum of education and no homeland ties, and work as domestics. After a year they could obtain landed immigrant status; after five – apply for citizenship. 2,690 entered Canada by 1965, and their families followed. Thirty per cent of the black populace of Canada is of Jamaican descent - a vast majority living in or around Toronto.

Eventually, we would hold our own at the El Mocambo nightclub, playing a week-long gig every month are so then move on to the Jarvis House, Mad Mechanic, the Roehampton Inn. The crowds on Spadina embraced us. Farther uptown, our music seemed alien and out of reach of the disco crowd. I’ve always played what I wanted; mostly oblivious to commercial trends. In fact, I wouldn’t recognize a hit record if it came labelled and certified as such.

Before a receptive college crowd, we played a mix of Marley, Peter Tosh; classics, ska, and soul music. This kept the audience engaged and solidly behind the band.

It was Eric Clapton’s cover of Bob Marley’s ‘I Shot the Sheriff’ that got everyone curious about the origins of the music. I was more familiar with Marley’s music than I realized. Somewhere in my evolution I did a ‘shop around’ at Sam the Record Man and bought Johnny Nash’s I Can See Clearly Now which included the hit, “Stir it Up.” A few years before I would discover that Marley had scripted these songs.

Marley played endlessly in our home along with Miriam Makeba and King Sunny Ade. Then came Burnin, the Wailer’s 1973 breakthrough. “Get Up Stand Up," "I Shot the Sheriff," "Hallelujah” clicked with a young white audience conditioned to smoking pounds of herb at Grateful Dead concerts. The beat was vastly different, as was the colour scheme and dance moves. There was also a growing curiosity with Marley’s embrace of Rastafarian culture.

Pablo, Wayne and I recorded five sides; “Sawbuck", "Streetwalker," "Promises," "Moonlight Lady," and "Nothing's Gonna Take You Away.” I played synth-bass on these sessions when George departed for Calgary after being diagnosed with a respiratory disorder exasperated by the pollution in our southern basin. HP and Bell released a single; the instrumental “Sawbuck,” then included “Streetwalker” in the Craig Russell film Outrageous. Chaka Khan covered “Nothing's Gonna Take You Away” after singer Debbie Ash from Buffalo, New York rewrote the verses. Khan included it on her album, Naughty. “Moonlight Lady” would be covered by singer Robert Burke and released in Jamaica in 1980.

With all this music kicking around the house, our son, ‘Baby Dub’ – Jesse, caught the vibe. At three years of age, Jesse would situate himself next to Pablo, pick up a pair of drumsticks and slap a few fills on the kit. Jesse would then clutch the chrome hardware and pull himself up to the floor tom and rock back in forth to Pablo’s hypnotic groove. It was only a matter of time before we bought Jesse his own set of mini Yamahas (a four-piece, full kit). From then on, the drums travelled room to room and wherever guests gathered for any given moment. Jesse would concertize.

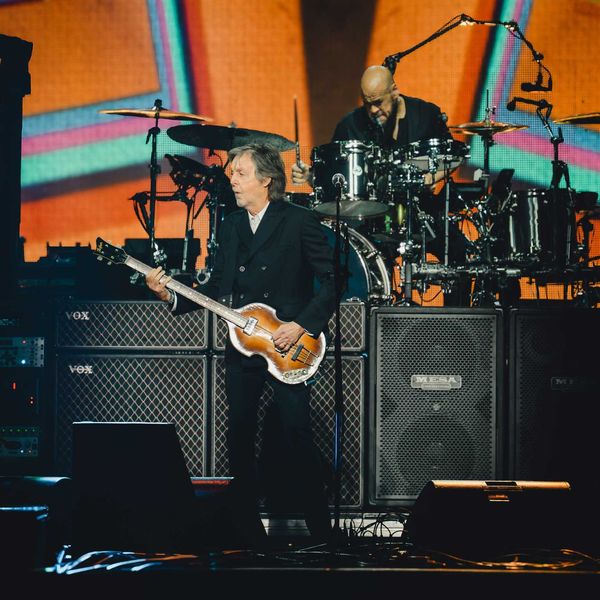

As each Marley album arrives, our house rattled and rolled back in forth under the influence of reggae rhythms. Then one day the announcement came – Bob Marley would be playing the second stop on his first North American concert in Toronto, June 8, 1975, at Massey Hall. This would be a homecoming of momentous proportions.

The band that night consisted of; Bob Marley (vocals, rhythm guitar), Aston Barrett (bass), Carlton Barrett (drums), Al Anderson (lead guitar), Tyrone Downie (keyboards), Alvin Patterson (percussion), and The I-Threes (backing vocals; Marcia Griffiths, Judy Mowatt and Rita Marley).

That memorable night, righteous vibes blanketed Massey Hall. There were kids as young as three and up and seniors in their eighties fanning away the humidity. The event was akin to a Sunday morning revival. Women dressed in their finest while the kids wore their Sunday best. Obviously, Marley’s music was something way beyond the pop ditties that temporarily sparked the brain then flittered away. These were songs that connected – songs that had an eternal feel to them -- songs with a soul, a message and a language all their own. People don’t memorize and cling to novelty numbers much longer than the latest ‘must-have’ gadget. They identify with greatness and embrace if there is purpose and principle behind the art and will remain loyal for years to come.

This was the Natty Dread Tour, in support of the new Bob Marley & Wailers album Natty Dread released in 1974 and later celebrated in Rolling Stone Magazine’s top 500 albums of all time. The album was a mash-up of writers, from the I-Threes to the rhythm section joining in.

Marley set the tone for the grand occasion by making a surprise appearance in the aisles leading to the main stage. He paused, kissed and hugged, shook hands and sported a broad contagious smile that imprinted itself on every one of the 2,500 faithful in the room. Ticket prices that night? $7.50!

From the downbeat, the band played with the precision of a well-drilled military ensemble. They ‘skanked, skaed’, and ‘reggaed’ to a relentless groove, with guitarist Al Anderson applying the precise number of blues-coloured fills. The sound system couldn’t handle the bottom-weight of Aston Barrett’s thunderous bass lines. It was a night mostly buried under a blown sound system and persistent distortion. The saving grace – Bob Marley and his charismatic stage presence and arresting dance moves. "You rock so, you rock so, you dip so, you dip so, you skank so, you skank so, and don't be no drag! You come so, you come so, for reggae is another bag!" - "Lively Up Yourself."

Marley and band played their eventual hits: “Trenchtown Rock," "Slave Driver," "Concrete Jungle," "Rebel Music," "I Shot the Sheriff," "No Woman, No Cry," "Natty Dread," finishing with "Get Up, Stand Up.” It was if an earthquake struck Massey Hall. The aftershocks continued until the last person was evacuated. Seats vibrate, and feet stomp. Everyone screamed for more. Then Marley struck one last time.

“Long time we no have no nice time. Do you, do you, do yah, think about that! Long time we no have no nice time, do you, do you, do yah, think about that! This is my heart, to rock you steady, I'll give you love, The Time you're ready, this little heart in me, Just won't let me be. I'm rockin.' Won't you rock with me?”

Tears, tears, tears. Everywhere you looked there were broad smiles and tears. The song is one of Marley’s earliest singles - one remembered by a nation of immigrants and held close to the heart. It was the best of humanity on display. Mothers and fathers, grandparents and children embraced and swayed to the easy reggae beat and sang along. The prodigal son had come home!

By 1976, Pablo, Wayne and I parted ways until congregating at Axis Studios in Atlanta, Georgia late 1978. We recorded two instrumental sides, one being the ever-popular “Summerheat (Symphonic Reggae),” the other an album cut, “After the Rain.”

We sensed then all was not well with Wayne. He’d spent a month living in the suburbs with us but stayed mostly secluded in the guest bedroom. As the years pass, Wayne would be diagnosed with schizophrenia. McGhie became homeless, drifting from neighbourhood to neighbourhood – porch to porch; and then he vanished. Some thirty years later Seattle based record company Light in the Attic began a search for McGhie, locating him the following year. A compilation of his early sides from 1969 that included musicians Jo-Jo Bennett, Everton Paul, Alton Ellis, Ike Bennett, Jackie Mittoo and Lloyd Delratt was released to worldwide critical success. McGhie lived under the loving care of his sister until passing away July 20, 2017, in her home.

By early 2004, and after years formulating a sound and experimenting, Jesse debuted his independent recording Campion Sound Clash and a rebranding; Jesse “Dubmatix” King. That would be followed by Atomic Subsonic in 2006, Renegade Rocker 2008, Juno award-winning System Shakedown 2010, a fifth Juno nomination for Rebel Massive in 2013. The music remained rooted in the historical tradition, Trenchtown rawness and vibrant cultural landscape of Jamaica. The albums include such eminent artists and practitioners as the late Alton Ellis, Michael Rose of Black Uhuru, The Mighty Diamonds, Horace Andy, Eek-A-Mouse, Linval Thompson, Sugar Minott, Ranking Joe, the late Wayne Smith and others.

Jesse would also contribute music to two films; the documentary RasTa: A Soul’s Journey produced by Marley’s granddaughter Donisha Prendergast and full-length feature Home Again, detailing the abuse and sordid treatment of Jamaicans deported back to their homeland.

Our big reggae family came together in 2013 with the formation of the Rhythm Express. Jesse, Pablo and I assembled a collective focused on classic ska and reggae. A band with big voices like Selena Evangeline, Gavin Hope, Michael Dunston and Stacey Kay; bold horns; Chris Butcher trombone and Bobby Hsu alto saxophone. Everton ‘Pablo’ Paul- drums, Dubmatix, bass, Jorge ‘Luis’ Papiosco, percussion, and ‘pops’ King on keyboards. Twenty-four singles and two albums were released over a two-year period and found their way into the mainstream of alternative radio.

That set of drums that put all of this in motion in 1974, loaned to Jesse by Pablo, stayed in the family sixteen years until Pablo formed the band Jamaica to Toronto and returned to playing publicly. Jesse had the set overhauled and restored to prime shape. To this day, it’s the sound of roots reggae on many a family recorded side. Much like the drum set that familiarized the planet to that Stax Records, Memphis soul sound. Pablo’s kit still packs plenty of history.

Marley left a profound mark not only on the commercial entities that use his music to lure sunbathers; the street-hawkers and merchants who capitalize on his legacy; but also, on those who seriously took his music and message to heart and share a reverence for the innovative rhythms and words that still resonate with the masses. We, as an extended musical family, celebrate 45 years of organ riffs, bass patterns, beats that sustain, and plenty of easy-skanking. We all still live on the Isle of Marley.

The accolades for Jesse King continue - honoured by Billboard Magazine (September 2016 issue), which crowned Dubmatix "Is This Love" rendition as the #1 Bob Marley Remix of all time! To date, the track has garnered over 14 million streams and growing!

2017 was another big year for Dubmatix' fans (2.8 million followers on Soundcloud and 270,000 on Facebook) as the prolific composer completed a remix for 2016 Grammy winners Morgan Heritage. Dubmatix also released a two-disc deluxe edition of Strictly Roots – which contained the Dubmatix Blaze Up Remix of "Light It Up”, which received rave reviews from outlets like:

Big Shot DJ Magazine - "On his interpretation, the Juno award-winning mix-master maintains the original's infectious quality while managing to turn up the heat a few more degrees for maximum dancefloor enjoyment.".

2018 saw the release of Overdubbed - Dubmatix meets Sly & Robbie with Grammy-nominated artists Sly & Robbie. Overdubbed hit #1 on the international reggae radio charts and was supported by over 1200 radio stations and media including Rolling Stone, The Wire, BBC and more.