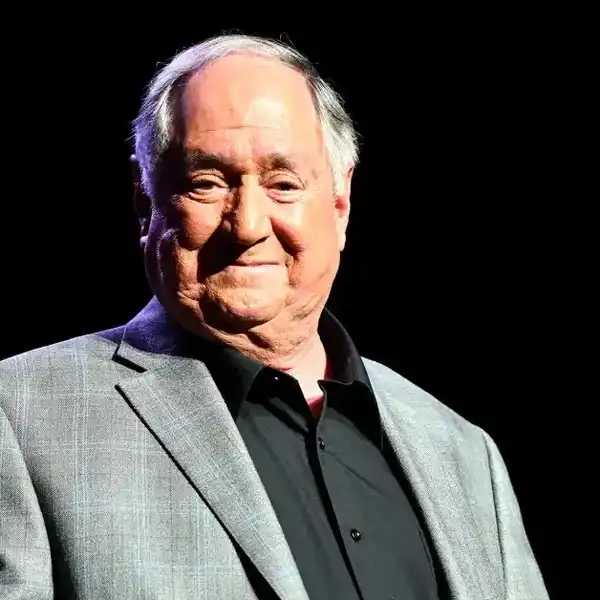

Jodie Ferneyhough's CCS Rights Mgmt Celebrates 10th Anniversary

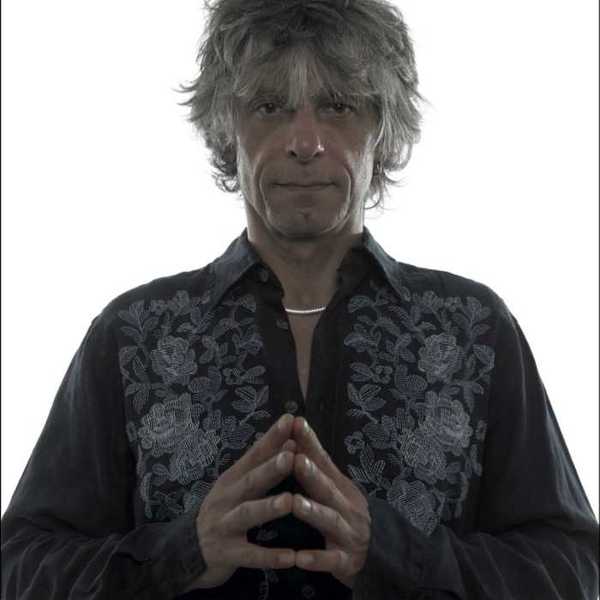

Jodie Ferneyhough’s CCS Rights Management turns 10 at the end of the summer.

By Karen Bliss

Jodie Ferneyhough’s CCS Rights Management turns 10 at the end of the summer. Usually, he’d throw a party, have some of his songwriters perform, but (like us all) he will have to be content with celebrating “in here,” and pat himself on the back for steadily building a company from the ground up that handles publishing administration, royalty collections, synchronization and licensing.

The first big announcement is the launch of a new neighbouring rights division, headed by Lee-Anne Wielonda, formerly of ACTRA RACs, concluding deals with Tate McRae, Spin Master Ltd, and Higher Reign Music Group, and bringing his full-time staff count to seven.

However, during covid-19, Ferneyhough is the only one who goes into the office.

“I come in everyday by myself because I pay the rent and I can't justify it staying at home,” he tells FYI over the phone. “We actually may have to go to a bigger office by the end of the year because there may be two more employees.”

Born in Welland, Ontario, Ferneyhough moved to Toronto in the early 80s and started eking out a living as an artist manager (Monoxides, Pigfarm). In the 90s, he earned extra income by working with Neill Dixon, sorting through the demo submissions and booking the 400-plus acts for Canadian Music Week, which he did for five years.

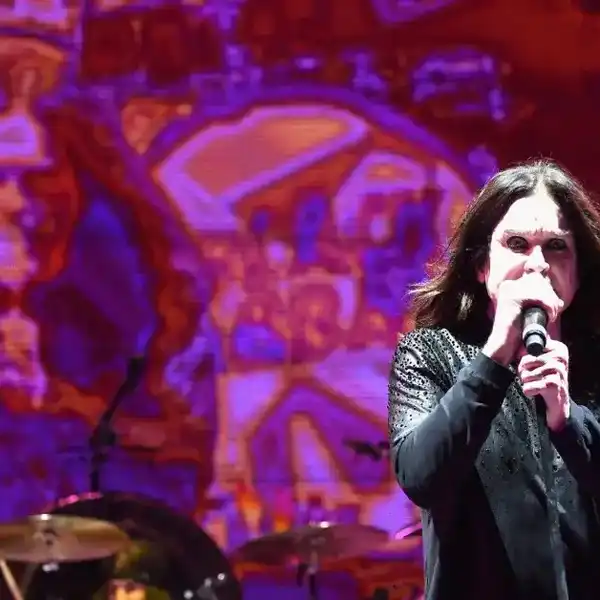

In 1997, he was offered his first publishing position, as creative director of peermusic, where he rose to general manager. In 2001, Universal Music Publishing Canada lured him away. He remained there for almost a decade, serving as managing director, and adding such acts as Sam Roberts, k-os, and Theory of a Deadman to the roster.

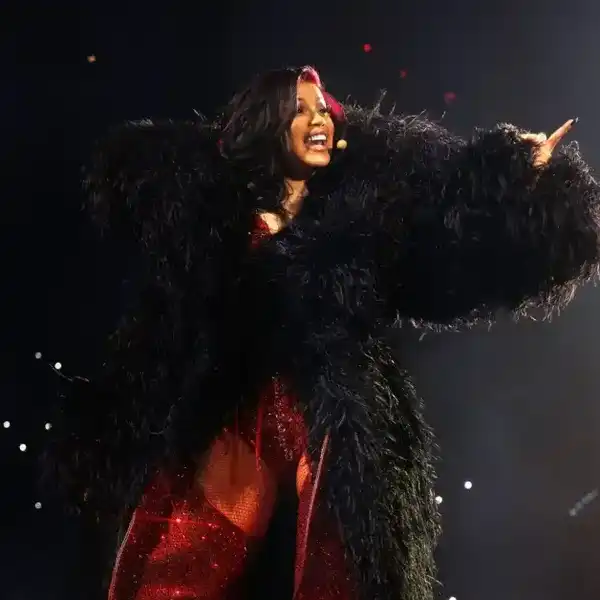

In 2011, after taking a loan on his mortgage, Ferneyhough bit the bullet and launched CCS, which now manages more than 150,000 copyrights. His direct signings include (the late) Glenn Gould, Carys, Yukon Blonde, Nuela Charles, and Poesy.

Also, of note, Ferneyhough sits on the board of the Brussels-based International Confederation of Music Publishers (ICMP), as well as Music Publishers Canada (MPC), SX Works, and steering committee of the CMRRA/SoundExchange. He is also a founding patron of the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame, and co-founder of the Unison Benevolent Fund.

FYI spoke to Ferneyhough about his 10-year milestone and plans for the future.

How much of your business is dependent on travel?

Yes, it is very much dependent on travel because as you have many contacts all over the world, you need to keep those relationships up, and you need to build new ones, and you need to nurture the ones that you have and find new opportunities for your artists and writers. So, yes, the business is predicated on travel.

Obviously, I haven't been in a plane for now over a year. I got home from Australia on March 14 of last year. What we've been able to do instead is take the time from all the travelling and we just hunkered down, cleaned up some systems, signed a bunch of artists, and made an excellent game plan for 2022. This year, it's all set up, co-writes and recording, and getting ready for next year with the hope that we're back in planes at the end of the year, top of next year, and rekindling those relationships.

You had a lot of years with a major and an independent publishing company. When you left Universal, what was the hole that you felt you could fill at that time with CCS?

It's the same hole that I believe that we can and are starting to fill now. My thought was that a lot of artists were missing money. One of the ideas that I had — and we do a bit of this — is a lot of older artists and estate artists were missing money completely or not managing their money properly or not finding all of their money. So, the goal of starting a rights management company was to be able to collect and monitor and administer all of a writer’s and artist’s rights. There are digital rights, there are neighbouring rights. We collect retransmission rights — that's for a film and TV company. There’s other income that is out there that can be collected. It was 10 years ago, but it wasn't a thing that a lot of companies were doing at the time.

With publishers and investors buying these catalogues from legacy artists, where does that leave artist development, and how does that landscape affect you?

We’re all hearing about all these multi-million-dollar, billion-dollar purchases. Everybody's out there buying up all these big [catalogues]. I started this company with a loan on my mortgage and we've built up over time. And because we flew under the radar, we do do development. We're working with a bunch of artists where all we've ever done is developed them, got [them] to the next level, getting co-writes happening, taking them around the world to get record deals or to do co-writes. The big deals just make everybody else's deals more expensive when they're bigger artists, but we're not buying a catalogue like that. We are in more of the development game and more in the middle game, if you will, with not those kinds of dollars.

Are you looking for investors? Developing songwriters will eventually, decades from now, be the legacy artists.

Absolutely. We'd like to continue signing bigger and bigger artists. I don't want to do the hundred-million-dollar deal. That's not what we're going to be built for, even with an investor. Yes, we are looking for investors at this point. But we're looking for that to build a very solid base catalogue, not going out and trying to just buy a hundred-million-dollar Neil Young catalogue. I can't compete with that; I don't want to compete with that.

You mentioned neighbouring rights earlier, but you've now started a division. Does that mean you weren't collecting neighbouring rights royalties before?

No, we were collecting for the artists that were directly signed to the roster. There are two separate rights, so we had to do two separate deals. We had a number of our artists — and still do — that we published that we offered neighbouring rights deals and did those deals for them. The neighbouring rights' division now is much more focused. It has outside writers and outside companies that we don't work publishing with, and we do direct deals with all the neighbouring rights associations around the world.

Publishing is probably the most complicated part of our industry. Do you want to explain in a nutshell what neighbouring rights is? Nothing to do with our neighbours (laughs).

(Laughs). It has nothing to do with neighbours and has everything to do with the performer or the performance. It’s the money that's paid to the artists, when a song is played at radio or other place, just the same as the money that's paid to the writer of a song.

And potentially the record label.

Yeah. Record label or the maker.

You always have big parties around Canadian Music Week. What are your plans for the 10th anniversary?

(Laughs). Nothing. We don't really know because of obvious reasons. We would’ve loved very much to have had a party or something. I think what you're going to see for the 10th anniversary is a bunch of announcements that will be made over the coming months. You’ll probably see some advertising; you’ll probably see some branding. And then, hopefully, in 2022, we'll do another party at CMW.

What's your involvement still with Unison?

Nothing really. I'm the co-founder with Catharine [Saxberg] and they are gracious enough to bring us into some high-level strategy meetings and told us early when the [Ontario government] gave them $2.5 million, but the day-to-day operation is being taken care of by Amanda [Power] and a great board. And I get the privilege of watching it continue to grow.