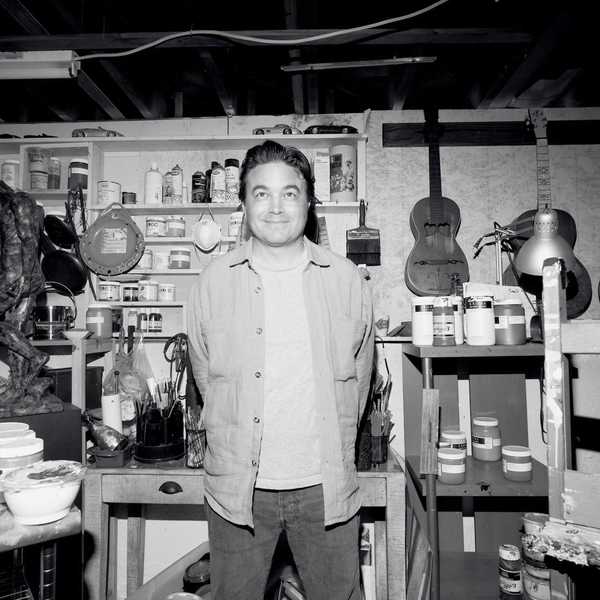

Five Questions With... Eamon McGrath

The hard-working Toronto troubadour is hoping his brand new album, Tantramar, will help him shake the punk-folk label. In this interview, he discusses that, his love of collaboration, and his desire for more communication amongst his peers.

By Jason Schneider

On his new album Tantramar, Toronto-based singer-songwriter Eamon McGrath couldn’t avoid capturing a specific time and place. The record—his sixth, available now from Saved By Vinyl—grew out of the year he spent as songwriter-in-residence at Sappyfest, the indie rock institution based in Sackville, New Brunswick. McGrath has been a part of Sappyfest since 2012, when he performed with members of local legends Eric’s Trip, leading him to later join Julie Doiron & The Wrong Guys, which further strengthened his ties to the scene.

Taking his Sappyfest gig extremely seriously, McGrath set a goal for Tantramar to create, in his words, a musical instrument out of the city, using its geography, stories, people, sounds and textures to make an indelible imprint on the recordings. Sessions were held at the condemned Sackville Music Hall, but audio snippets of a train whistle heading through town, and a family of racoons living under the ruins of George’s Roadhouse also found their way onto the album.

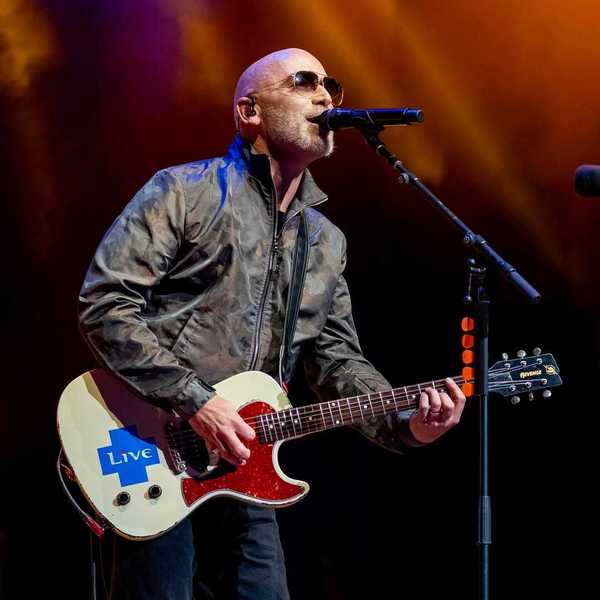

As well, McGrath called upon several of his regular collaborators to join him, such as Jose Contreras of By Divine Right, and Leah Fay and Peter Dreimanis of July Talk. That’s Dreimanis on background vocals and piano on the album’s first single “Power,” the video for which was made by Guadalajara-based filmmaker Fernando Castanier.

A tireless road warrior, McGrath is back on tour now with dates in Ontario leading up to his North By Northeast showcase at Toronto’s Bovine Sex Club on June 14, before heading to Alberta for shows in the latter half of the month. You can keep tabs on his movements at eamonmcgrath.ca.

What makes Tantramar stand apart from your previous work?

This record was made with a very clear and distinct attempt to be distant from anything that could be easily categorized or associated as “punk rock.” I made a point of avoiding basic rock as much as possible and—although I might play the songs solo depending on the tour—I didn’t want to have any solo acoustic tracks on it to avoid any “folk/punk” or [Chuck] Ragan-esque comparisons. That’s something that’s both blessed and haunted me from the start of my career.

As I leave my 20s for a new decade, that youthful urgency and burning desire to be associated on some musical level with Discharge or Motörhead is definitely leaving my life with it. On my earlier records, like Young Canadians, there were some tracks that on one level tried to channel that more aggressive hardcore punk energy or production style, bridged with country or folk music. Now I’d just rather make more beautiful, ambient, esoteric music and pay more attention to the sound and feel of the songs rather than the urgent and ballistic energy you can capture live. The spirit will always be there, in the form of a fierce commitment to DIY and to the fact that somehow I always end up as an artistic outsider no matter how I get categorized. But I wanted to make a record that you couldn’t use the word “punk” to describe it whatsoever.

What songs on the album do you feel best capture your current musical vision?

“Chlorine” I think captures where my headspace is at. It’s dynamic, textural and weird, but it’s got a big chorus, and you can raise a pint glass to it. My friend Will Whitwham of The Wilderness of Manitoba and I were talking recently about how to describe my music, and he mentioned that it was really just “sad music you can party to.” A lot of my favourite all-time records are exactly that: Television’s Marquee Moon, The Replacements’ Tim, the first Smiths’ album. These are all records you can put on at a house party and they don’t feel strange and awkward or bring people down. People get wrapped up in the energy and feeling, and ride that emotion like a wave, but are also subconsciously attentive to the darkness and gloom. I love that paradox and I want to capture that dichotomy.

The album again features some high profile collaborators. What's the key to a good collaboration?

The key to collaborating is to completely trust in the other person and open all the doors to allowing them to play exactly what they’re hearing or feeling in the song. You didn’t ask someone to be a part of what you’re doing to have you explain it to them, you asked them because you value their perspective and outlook on the world and want them to share it with you as a listener, along with whoever’s going to be listening to the finished product of the record. Collaboration is about wanting to be one voice in a field of collective voices. Your role is only to facilitate and explain the situation.

What are some of your best touring tips, and your best touring story?

I think that Thor Harris from Swans said it best in a piece about touring from a few years ago: “Eat more oranges and drink less beer.” It really does kind of boil down to that. You’re going to have the experience that you and you alone allow yourself to have. Maybe you’ll have these incredible experiences after midnight every night, but you’ll pay for it with violent hangovers until soundcheck every day, and that’s totally fine, but that’s the way it is. There’s no one to blame for how you feel on the road other than yourself. You’re in control of your own fate one hundred percent of the time and it’s crucial to realize that.

As for touring stories, every tour you do supplies you with enough stories to fill a book and every single day is just another chapter. I recently did a tour of Newfoundland and the first show outside of St. John’s after the LawnyaVawnya festival was a gig in Pasadena at this garage-turned-venue that the owner created by taking a sledgehammer to a wall, just in time for the gig. I think that’s a pretty cool story.

If you could fix anything about the music industry, what would it be?

I think that there’s a toxic lack of communication—between bands, between promoters, between artists in different art forms, between festivals, between audience members. It doesn’t bode well for a microscopic music community like Canada when nobody is talking about how everyone can collectively benefit. For example, bands from Ontario who are touring out west should figure out their routes before there’s any kind of competition in cities of less than five hundred thousand people on Tuesday nights. It makes no sense. There’s more than one way to draw a line on a map. If there’s anything I want to take away from my career, it’s that I tried my hardest to create a sense of community in everything I do. There are political connotations to that that far exceed explanation and I think if musicians and artists all banded together you’d see real change in the world.