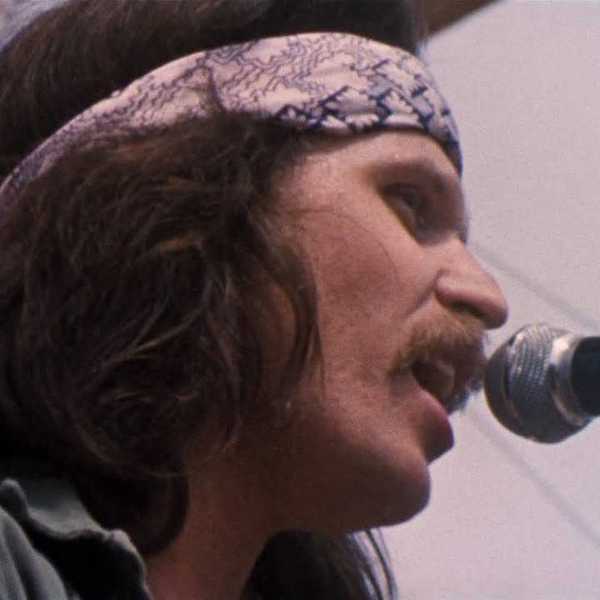

Five Questions With… Chilly Gonzales

The iconoclastic Grammy-winning pianist and composer is about to release the final album of his Solo Piano trilogy. In this typically entertaining interview, he describes the making of the record, his love of the underdog, and his satisfaction with the current state of the music biz.

By Jason Schneider

Grammy-winning Canadian pianist, entertainer and composer Chilly Gonzales will release the final album of his Solo Piano trilogy, Solo Piano III, on Sept. 7 through his Gentle Threat label. The set comes six years after Solo Piano II and features more dissonance, tension and ambiguity as a reflection of our current state.

It’s being preceded by the single “Pretenderness,” a piece dedicated to the 19th century German female pianist and composer Fanny Mendelssohn whose body of musical work was mostly hidden in her brother Felix Mendelssohn’s shadow, since, at the time, she was not allowed to have a profession just because she was a woman. It follows the pattern of Gonzales’ other dedications to other cult heroes who never reached their full potential due to social restrictions that held them back.

For Gonzales, born Jason Beck in Montreal, rebelling against music industry norms has been his mission for the past two decades since he left the North American pop world behind and reinvented himself in Berlin. Known as much for his intimate piano performances as for his showmanship and composition for award-winning stars, “Gonzo,” as he is known to close collaborators, aims to be a man of his time, utilizing his classical and jazz training but with the attitude of a rapper.

He holds the Guinness world record for the longest solo concert at over 27 hours and has performed with and written songs for the likes of Jarvis Cocker, Feist and Drake, among others. In 2014 he won a Grammy for his contributions to Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories and composed the best-selling book of easy piano pieces, Re-Introduction Etudes. It’s all part of his over-arching goal to offer a new perspective on “serious” music, which now also includes his recently established music school in Paris, the “Gonzervatory.”

A career retrospective documentary directed by Philipp Jedicke called Shut Up And Play The Piano will be released this fall, and Gonzales returns to Canada in October for concerts in Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Quebec City. For more information go to chillygonzales.com.

What was your approach to creating the pieces for Solo Piano III?

I took a sabbatical year and let myself drift creatively without any deadlines or plans. I started composing, and I wasn’t sure where these pieces would end up. Even though every song I compose begins at the piano, I’ll often hear strings, or I may imagine the piece as a collaboration with a rapper or electronic producer. By the end of the sabbatical year, the pieces were stubbornly refusing to be anything other than pure instrumental pieces. That’s when I knew I was ready to close the solo piano trilogy.

You’ve stated that a lot of your work is inspired by underdogs, like the current single “Pretenderness.” Is that something you relate to personally?

It’s inspiring to think about the people who came before me who didn’t conform to existing tropes and roles. Anyone who imagines creating something original is an underdog. Some have life circumstances that make the struggle especially difficult and admirable, as is the case with many of my dedications.

You’ve collaborated with a wide range of high profile artists. How do those collaborations generally come about?

Evil record company bribes. Or total serendipity and coincidence.

You also have dedicated yourself to making classical music relatable to the current generation. It reminds me of Frank Zappa's famous credo—via Varese—“the present day composer refuses to die.” Do you subscribe to that belief?

I’m not trying to make classical music relatable, in that I find it’s not relevant to today’s musical landscape. I simply use the tools and some of the aesthetics of this trove of European music to make my kind of pop music. I’m not consciously trying to be a gateway drug to classical music. Perhaps I’m trying to show how classical music isn’t so different in its underlying philosophy as any other kind of music. Music is storytelling and involves tension and release, repetition and surprise. That’s pretty much universal in Western music at least.

If you could fix anything about the music industry, what would it be?

It’s great like it is! The internet made it possible for me to find an audience, and for an audience to find me. Imagine trying to convince a major label to sign a rapping pianist in a bathrobe when there were so few gatekeepers to get past. Also, the implosion of the recorded music business model has put the emphasis back on performing, so I’m in an excellent position to thrive in this environment.