Down The Road Apiece

Our intrepid correspondent reflects upon the pandemic blues faced by musicians, life on the road, and gigs from long ago, and offers an excerpt from his upcoming book about the ‘60s.

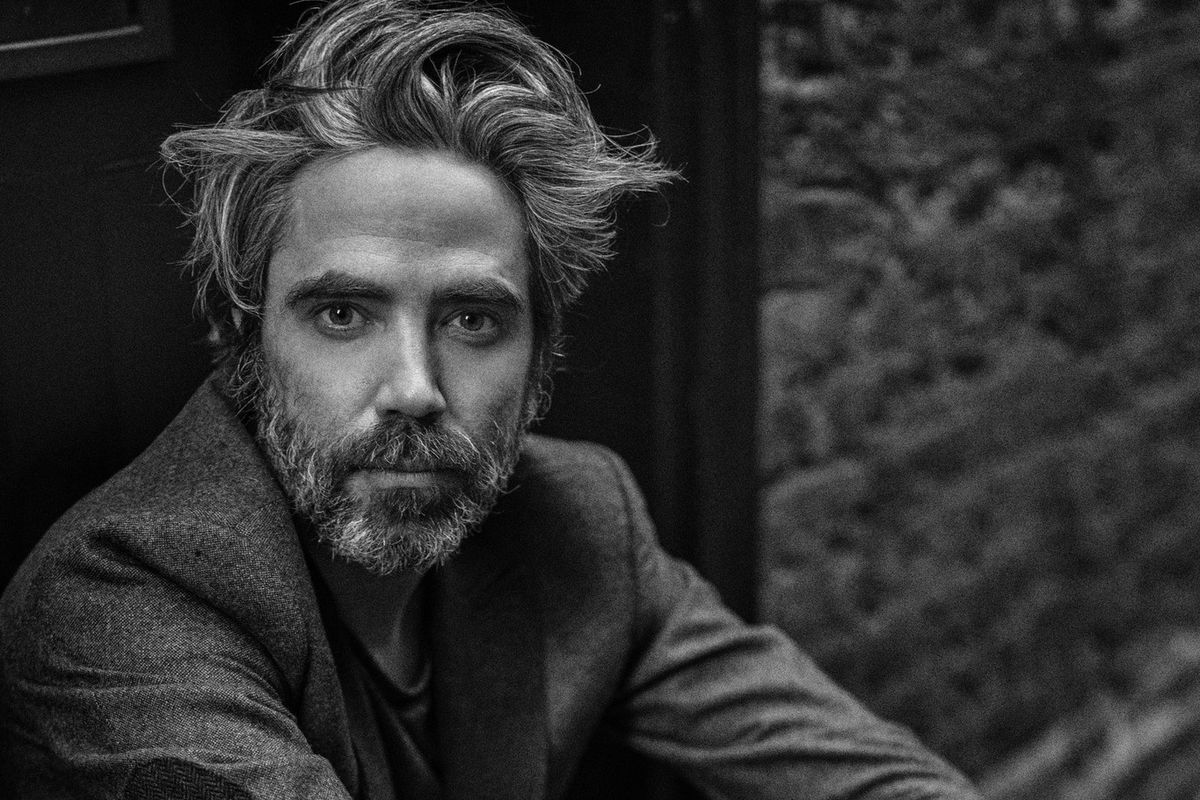

By Bill King

At this moment, nobody’s going anywhere, especially players. From interview to interview, it’s evident a good many earn their living from touring and for the foreseeable future that's out of the question. Those of us who work on both sides of the music industry had to adjust and figure out ways to keep both sides in play. With 32 years behind us at the Beaches International Jazz Festival, it’s been imperative we move with the times, which speaks to this year's virtual streaming festival that is pieced together from the content that the musicians sent in.

There’s nothing more painful than sitting around and waiting for the next gig, whether in a club, studio or concert setting. It was several years in between for me playing any location more than a night or two when I hooked up with Jo Jo Bowden and Collin Barrett at N'Awlins. The first months of three one hour sets a night nearly killed me. Not the sitting, but the singing. Then I remembered there was a time I played six hours a night in Vegas. I wondered, are we at a juncture when such things are more or less etched in the history books.

I love reading road stories, not from the stars which exist in a bubble, but those who drive the long miles, stop along the way at a roadside diner, sleep in a seedy hotel room fit for a vagrant. These are the places where tales are born and passed down generation to generation. I’ve spent the last six months writing a book about the ‘60s and poking the brain for memories and am blessed with a photo enhanced mind, not a photographic memory but one that registers and documents everything visually. I think that’s why photography found me. In doing so, I recalled what it was like as a teenager to have a few gigs under my belt and where I wanted to be after leaving home. It’s 1965, and I’m ready to rumble. I’m sure there were moments you’ve wished the same. Here’s a passage from the book.

I dreamt of breaking free; those long drives musicians reminisced about through the south, past fields of sprawling kudzu and fog-shrouded back-roads. The perfect way to decompress after a long night playing on the funk side of town. I was ready to climb on the band bus, back of a station wagon, and begin my journey.

The many one-nighters I’d already played were mostly local, no more than a hundred miles in all directions. I knew radio was the best company a carload of musicians could ask to free the mind of setlists and missed opportunities with local groupies. No time for a sleep-over or three-dollar T- bone steak. I’d already ridden in a crippled station wagon, taken on road grime and patches of red clay; the windshield a graveyard of suicidal beetles, palmetto bugs, wasp, and grasshoppers. Above me, the sleeping branches of tall pines, in the distance, weeping willows near where a mockingbird eye-balls and serenades all night-drivers.

I imagined my next gig would be with one of those southern touring bands, a 225-mile drive and arrival just past noon. I envisioned a stopover at one of those WLAC kinds of stations and a DJ yelping like he was riding an amphetamine high. Then there was the insomniac basement preacher with a 100-watt transmitter selling Jesus’ and recipes for warding off imagined demons. Preacher man sermonizing, “Satan will boil you in a pot of blood and snakes.” I could hear the radioman bark, “Don’t forget tonight at Round Hall, The Mob – big funky rhythm machine from Chicago. $2 off if you bring a date. During the ‘60s, nothing much happened after 7 p.m. in rural communities, other than those night creatures trolling the landscape for a good meal.

It’s three in the morning, Otis Redding in repeat cycle and a DJ storytelling long into the dark hours. I fantasize about what it would be like playing in a soul band and singing much like Ray Charles and Otis Redding. Curve those white notes into blue notes and “sweet sing” when expected. The DJ rambles on, “Did you know young Otis ran barefoot through these woods surrounded by copperheads, diamondbacks, and coral snakes and spiders the size of small animals, the son of a preacher man born of hard Georgia soil. There you have it, one solid hour of Dawson, Georgia’s own Otis Redding, born 1941 right down here where the smokehouse hams it up, and bird-hounds chase peasant for sport, this is Captain Ray Williams WXBX signing off. We’ll be back on the air in three hours with the farm report.”

Eventually, we pull into the next town, set up, then play four sets of Wilson Pickett, Willie Mitchell, Ike and Tina, some Little Richard, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, Lowell Fulsom, and Otis himself. After the gig and mostly sleep deprived, we laugh, eat shitty food and reclaim the same seats we came in. With trailer packed and all accounted and another a hundred and eleven miles to Tallahassee, we fall back into a radio trance; drummer mumbling some nonsense about some sweet honey left behind he’d marry if time permitted. The white noise of roadside cicadas’ alert us roll front and back windows tight. Through the hours I watch the miles click by like a late-night newsreel. I’m the boy in a band of men, and never sure of what they are laughing about, but I laugh along. I downed my first beer at sunset, the last after gear packed. Good Lord, I’ve got to piss. Can I get a witness?