Three Radio Insiders on the State of Canadian Radio

To get a fix on the volatile situation, Bill King speaks with three veteran insiders with unique insights.

In early February, Bell Canada Enterprises (BCE) announced a substantial workforce reduction, initiating the elimination of 4,800 jobs, equivalent to approximately nine percent of its workforce. This significant downsizing, coupled with plans to divest 45 radio stations nationwide, underscores one of the most extensive layoffs in recent Canadian history.

The decision continues to reverberate through an industry already grappling with diminished revenues and persistent losses in BCE's news division. The move reflects the company's strategic imperative to streamline operations and navigate the challenging terrain of the contemporary market.

This development unfolds against the backdrop of an industry facing broader economic uncertainties.

Across the media landscape, adjustments are being made, and the voices in opposition are growing louder. The upside is yet to be felt, but there remains real optimism. That view originates from outside the corporate conglomerate purview and within the hearts and minds of those who prioritize art over commerce — the broad picture — the wide playlist.

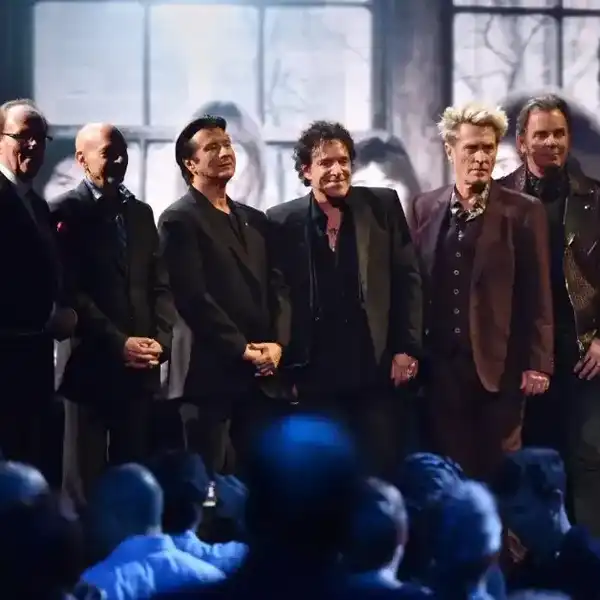

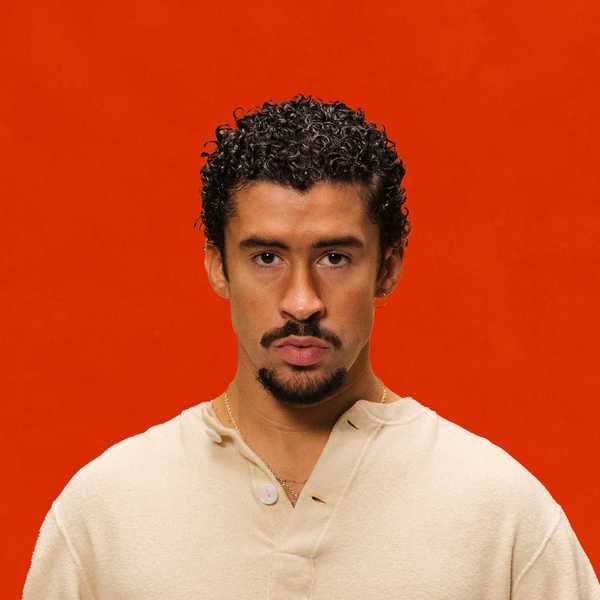

I spoke with three insiders with unique insights. Ken Stowar is a station manager and programmer at leading campus radio station, CIUT 89.5 FM, the University of Toronto. Retired GM and radioman, Pat Holiday was voted Canadian Program Director of the Year twice and Canadian Station Manager of the Year three times. Durham Radio's Doug Kirk recently acquired three stations outside Toronto from Bell, which brings the family total to ten small market entities.

I began by asking Stowar a simple starter question. What's right with the radio?

"From my perspective, there isn't much right about radio at all," he says. "I'm talking about the commercial radio environment. Suppose I consider the campus and community radio sector, which lacks the financial or human resources of the retail radio sector. In that case, a lot is going on.

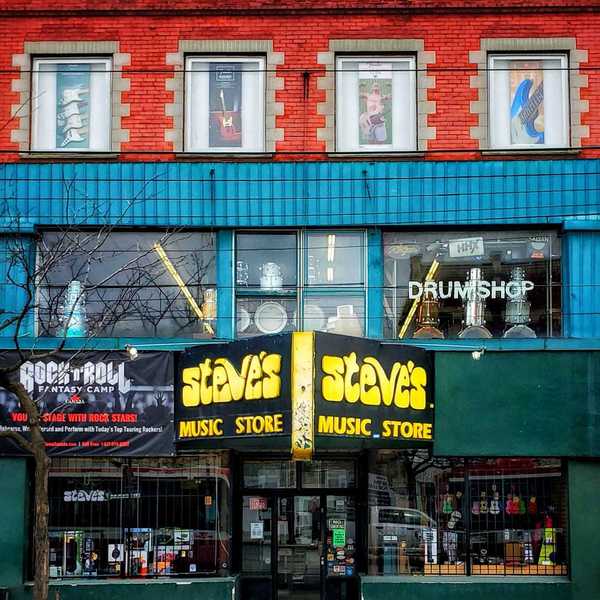

"Campus radio is essential to people, and it should be more critical. The campus community radio sector does an excellent job of tying into diverse, inclusive and varied communities. It takes on local and topical stories and delivers on the air. The music presented is distinct, as you would find in the campus community radio sector over a broadcast week. Any station could play 1,200 or 1,300 individual tracks a week. That truly separates the campus radio sector from what goes on in the commercial radio sector."

For Holiday, despite recent news, success in radio is as simple as it used to be.

"From my view, being out of radio [now], success with a radio station is the same as 50 years ago," he says." If it survives, it'll be the same 50 years down the road. You had better hire great air talent, let them loose, care about the music and product, and do anything that makes people passionately love your station and tell others. Yeah, it's just that simple. Truly.

"But a few things are in the way. In Canada, the government has outdated rules. That ship sailed in the '90s with the net coming in. Everywhere else, hedge funds pay stupid multiples (prices) for stations and then squeeze them to death for a return. The only 'save' now is to restructure debt like iHeart pulled off or go bankrupt with a fire sale on assets so others can pick up the baton and build something that matters. Luckily, that's happening now and will likely escalate because of today's interest rates. Trust me, it's a good thing, assuming the new owners pay reasonable prices."

Kirk has a strategy to revitalize and look to the future: Relocalization.

"We bought the three stations from Bell," he says. "CKPT and CKQM in Peterborough and CKLY in Lindsay. These are historical stations. For at least 40 years, they have been in the market. They're bedrock there. Our job is to take those stations and run them. We're independent operators. Our strategy is to be distinctly local, do as much local programming as possible, and do as much ancillary work, covering and promoting community events. You know, [that can be] as corny as the Santa Claus parade, showing up for everything.

"We are getting behind causes, promoting community service work. We do that. We have a program on all our stations where we do community events. Coverage will include a cruiser vehicle with a personality on the weekends out doing reports —from 4 to 6 community events. That's key to us, and it's been successful in other markets."

Stowar worries about those graduating with journalism degrees into a diminishing job market.

"We still have institutions pumping out hundreds of radio and television broadcast students. I'd like to know where they're going to go. I speak to many radio students who're discouraged because they're being taught to fit in the cookie-cutter mold. That's what they're being trained for. But when I spoke with them, I said, if you dislike what's happening, you need to get into the state of authority, decision-making, and affect change. Radio will be around for a long time. It has survived an onslaught of other challenges throughout its huge decades-old history. And what radio is up against right now is certainly yet another challenge. But radio is still the best medium."

Is there a middle ground solution? "Develop some new formats," suggests Stowar. "When I look at CIUT as a campus radio station, I look at some shows we do that are based around funk or psychedelic rock or whatever it is. There's this unique, ongoing audience. There's a thirst for all kinds of music to be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

"Why are they running and playing 300 songs, of which 15 or 20 get played 60 or 70 times a week? It does nothing for the Canadian music industry. What the commercial radio stations do is no secret: they take maybe ten artists and play their songs 35 times a week. You've got your 35% Canadian content. That's got to change."

Passion for radio flows thick through each person's attachment to the medium.

"I first got into radio when I was about five," says Kirk. "I was a kid looking at the radio over the kitchen table. The draw was the magic of the radio. This little box carried you all around the world, and you got information. What worked as a teenager, of course, was the music. Getting into music radio at that point was the channel into the world of top 40, music, and all the things you like as a teenager. After I grew up, had a career, and made a bit of money, I stopped being a fan and actually put my money where my mouth was."