The Canada Black Music Archives Launches Searchable Database of Musicians

Executive Director Phil Vassell says he wants to show how artists like Drake and The Weeknd "are standing on the shoulders of people who came before them."

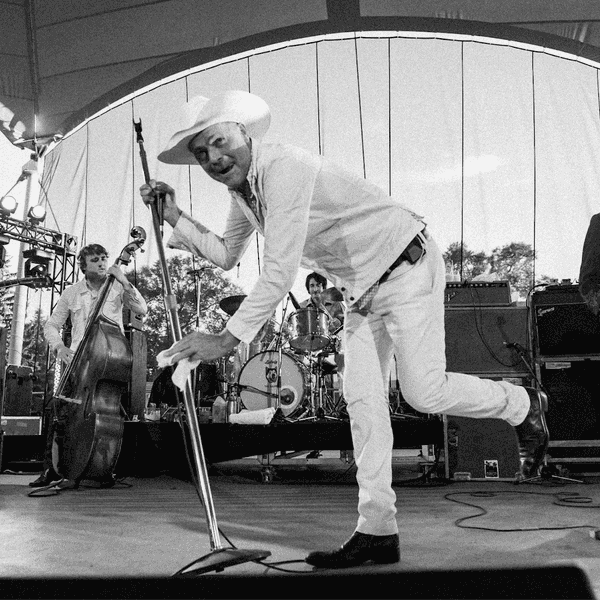

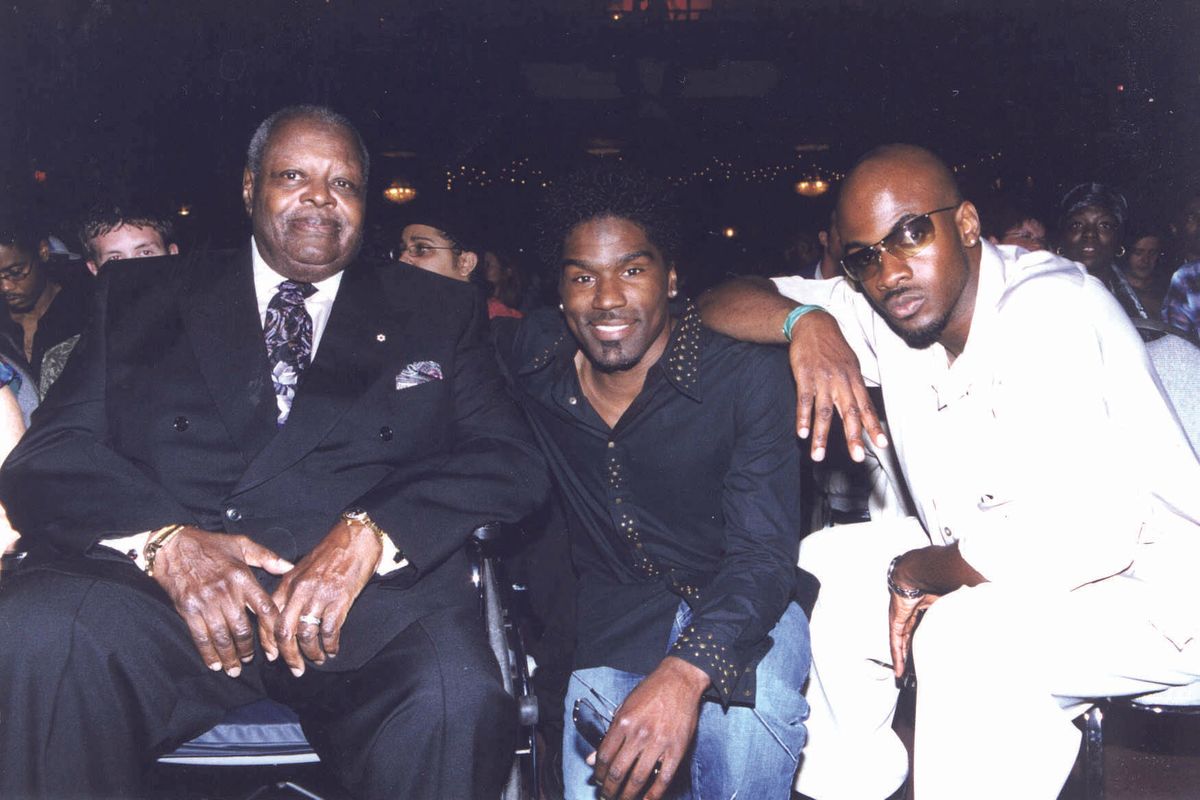

A photo from the archive: Oscar Peterson, Glenn Lewis and Maestro at the UMAC Awards, 2002

How many Canadians have heard the name Daisy Peterson Sweeney? Many will know her brother, legendary jazz pianist Oscar Peterson, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award recipient and Companion of the Order of Canada. Sweeney, who taught and mentored artists like organist Joe Sealy and pianist Oliver Jones, is less recognized.

“She’s an unsung hero,” says Phil Vassell, Executive Director of the Canada Black Music Archives (CBMA). On Nov. 23, the CBMA launched their digital archive, which works to address the under-representation of Black contributions to Canadian music by telling stories like Daisy’s.

Vassell says the idea for the archive came out of the pandemic. Vassell has spent decades championing Black artists in the Canadian music industry. In 1991 he founded WORD, a Black culture magazine, with his wife Donna McCurvin, which also later spawned two music festivals: the Toronto Urban Music Festival and the Caribbean and African music festival IRIE. When the pandemic hit in 2020, Vassell explains, they started thinking about what they could do with the immense archives they had built through these ventures. At the same time, museums and physical archive spaces were largely closed to the public.

“That led us to landing on the idea that we needed to make this archive digital and therefore accessible, and a little bit more foolproof in terms of people accessing it without having to go into a physical building,” Vassell says. As the concept of a digital archive started to take shape, they began working with advisors including Much VJ Master T, writer Klive Walker, and DJ Andy Williams.

“As we started speaking to some advisors that we had pulled together we realized that there was a huge hole to fill in the national narrative about Canadian music,” Vassell says. The CBMA was founded in 2020 and has spent the last three years building their digital repository, with the goal of emphasizing Black contributions to Canadian music culture.

There's a searchable database of artist pages, complete with biographies, photos and videos, press clippings and discographies. Users can sort the artists by genre, region or decade, to find what they’re looking for — or just scroll through and explore. Spending some time with the archive, it also becomes clear how early artists laid the groundwork for others over generations: a search for Sweeney, for example, also brings up the artist pages of Sealy, Jones, and the Juno Award-winning Montreal Jubilation Gospel Choir.

“First and foremost this is an educational project,” Vassell says. “This information is not readily accessible anywhere.” He imagines the archive’s applications for students at all levels, from elementary to post-graduate. Schools like the University of Toronto and York University have already listed the archive as an information source for students.

Before the CBMA, there was no place where all these stories were collected and housed. “We’re trying to change that,” Vassell says, “and to make sure that these people are part of the Canadian narrative in terms of music.”

He points out that in genres like hip-hop, a lot of Canadian artists have historically released music at the independent level, meaning there is often less attention paid to their impact. With more Black Canadian artists getting global recognition, however, he thinks the time is ripe to shed light on the artists who came before them.

“Drake and The Weeknd — they became world superstars — and all the sudden people wanted to hear more about who else is in Canada,” Vassell says.

Accessibility is a priority for the archive, meaning it will remain primarily digital. But the CBMA celebrated their launch with a pop-up event in Toronto, featuring banners highlighting some of the artists in the archive. They hope to hold pop-ups in other cities around the country, and are eyeing a potential event in Halifax next year, to coincide with the 2024 Juno Awards.

The Toronto pop-up also had performances from reggae artist Jay Douglas and Liberty Silver, who in 1985 became the first Black woman to win a Juno Award. In fact, she won two in the same year, in different genres: Best R&B/Soul Recording of the Year for “Lost Somewhere Inside Your Love,” and Best Reggae/Calypso Recording for “Heaven Must Have Sent You” with Otis Gayle.

“These are some of the stories that are lost, if you will,” Vassell says of Silver. “And we want to recapture that information in a way that people can know that all these internationally famous artists now, the Drakes and the Deborah Cox’s of this world, that those people were and are standing on the shoulders of people who came before them.”