Why This Remote Quebec Festival is One of Canada's Most Unique Music Festivals

The new documentary 'It Could Only Happen Here' tells the story of the FME, the Festival de Musique Émergente, which takes place every year in remote Rouyn-Noranda.

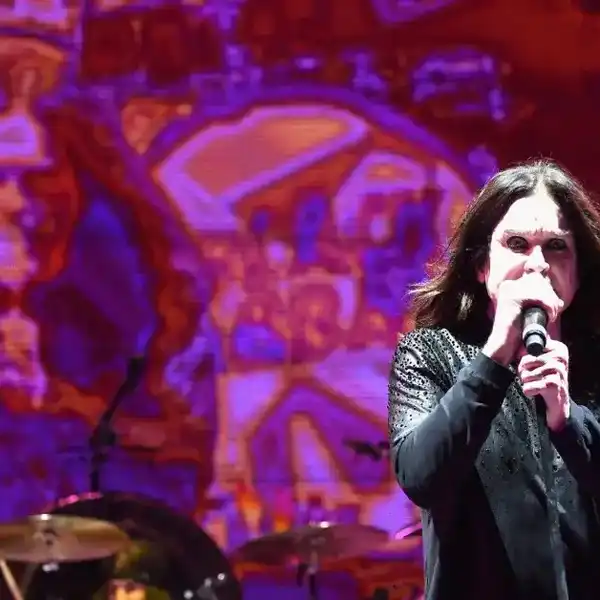

Elisabete Balčus performing at FME

A new documentary is showcasing the wild and unique spirit of an alternative music festival that borders Quebec and Ontario.

Eight hours north of Montreal, in the city of Rouyn-Noranda, residents and visitors gather every Labour Day weekend for a twenty-year tradition: the Festival de Musique Émergente, which brings rising Canadian and international acts to the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region.

In It Could Only Happen Here, director Stephan Boissonneault captures the festival's raucous energy via interviews with artists and organizers and lots of performance footage from the 2022 edition, featuring Canadian musicians like Rich Aucoin, Ombiigizi, Bonnie Trash, Fernie and Chad VanGaalen, as well as international acts like Latvian artist Elizabete Balčus.

The documentary screened at Montreal's Cinematheque Quebecoise this week, and Boissonneault is hoping to bring it to film festivals this year.

Boissonneault first attended the festival in 2021, and recalls how much more welcoming the environment felt than other festivals he'd been to. He went alone to cover the festival as press, and within hours, found himself part of a group.

“We were our own little community hopping from show to show," Boissonneault says.

The documentary opens with footage of post-rock experimentalists Yoo Doo Right performing a secret alley show in 2021, with voiceover from Boissonneault explaining that he climbed a shaking ladder just so he could capture the moment. "This could only happen here," he told himself.

Throughout It Could Only Happen Here, artists and community members reiterate the sentiment. Boissonneault highlights festival volunteer Oussama Affane, who moved from Morocco to Quebec City, and after attending FME, was so taken by the local community that he decided to move to Rouyn-Noranda.

Boissonneault suspects that the festival's magic has something to do with Rouyn-Noranda's remote location. Co-founder Jenny Thibault explains in the documentary that she and her friends were tired of always driving to Montreal to see music, so they decided to bring the music to them. With fewer entertainment options than in major cities, Rouyn-Noranda locals — the city has a population of roughly 40,000 — are loyal supporters of FME, showing up in droves every year to check out the festival's eclectic lineup.

FME bookers Mothland work to select acts that are left-field and up-and-coming, which means attendees are always in for something new. Boissonneault recalls seeing 70-somethings in the crowd at a high-volume Yoo Doo Right show (hopefully, they had their earplugs in).

The festival also has a reputation for throwing a pretty good party. Boissonneault provides a brief overview of Rouyn-Noranda's history as a mining city in the early 20th century: Noranda was the company town, and Rouyn, across Lac Osisko, became the party town, with hotels, bars and theatres.

That nightlife culture translates into a festival where there's a sense that anything can happen. Thibault tells the story of how in 2009, Montreal band Random Recipe played a spontaneous late night show at a poutine spot called Chez Morasse — Boissonneault includes footage of the packed diner performance — beginning a tradition of bands taking it upon themselves to plan secret shows at the festival. Eventually, the festival folded the secret shows into their programming, working with the chaos rather than squashing it out.

This kind of DIY attitude is reflected in Boissonneault's approach to filming — much of the concert footage is shot on GoPro or iPhone, placing the viewer in the middle of the action, trying to catch a glimpse of Gus Englehorn's playful punk or gazing up at Ombiigizi's Daniel Monkman and Adam Sturgeon as they trade-off vocals.

Boissonneault's artist interviews, meanwhile, provide an inside perspective on what makes the festival meaningful for them. Noise rock band Gloin emphasize the festival's artist-centric approach, with hospitality services that help artists feel welcomed and wanted. Rock duo Bonnie Trash appreciate how the festival brings together Anglophone and Francophone artists, something they say they haven't encountered elsewhere.

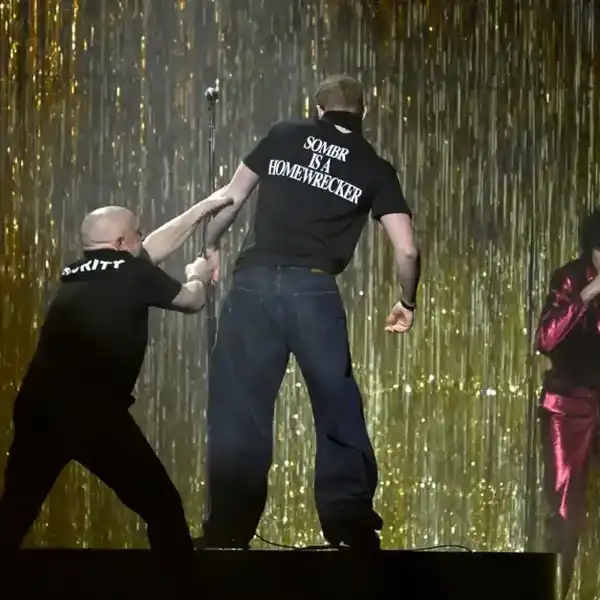

"The one thing that FME does better than probably any other festival is it gives so many opportunities to these bands to play," Boissonneault adds. "Smaller bar shows, outdoor shows, some of them are on the main stage even though they’re not huge yet,” he continues. Boissonneault points to a band like La Securité, who played one of their earliest shows on a rooftop at the festival in 2022, and have since gone on to build a strong profile for themselves with the release of 2023's Stay Safe! The festival also brings in industry members from France, England and elsewhere, connecting them with Canadian artists.

There are many Canadian music festivals located far from major urban centres, but FME's particular mix of location, curation and spirit has earned it an impressive stature and a special place in the hearts of artists and attendees. Boissonneault encourages all music fans to give the festival a shot, even if they don't recognize any names on the lineup — chances are many of those names will be playing bigger stages in years to come.

"Just check it out," he says. "It is a pretty far drive, but honestly it’s worth it.”