Canadian Artists Respond To Pitchfork Restructuring And Layoffs

Condé Nast announced this week that the taste-making music site will be folded into men's magazine GQ. Some worry the transformation of the publication and others like it will make it harder for their music to break through.

An influential music publication is making major changes, and Canadian artists are concerned about what it could mean for the future of music.

Earlier this week, Anna Wintour, chief content officer of media company Condé Nast, announced that Pitchfork will become a vertical at men's magazine GQ and will undergo restructuring and layoffs. Many Pitchfork employees were laid off, including features editor Jillian Mapes, as well as longtime employee and executive editor Amy Phillips. Current editor-in-chief Puja Patel is also exiting the site, according to Wintour's memo to staff.

The news comes shortly after the sale of music platform Bandcamp, which saw the layoffs of several editorial staff at Bandcamp Daily, and amidst a climate in which music journalism jobs are disappearing. (At the same time digital media workers, like those at Pitchfork, are unionizing. Pitchfork Union condemned the layoffs in a statement this week.)

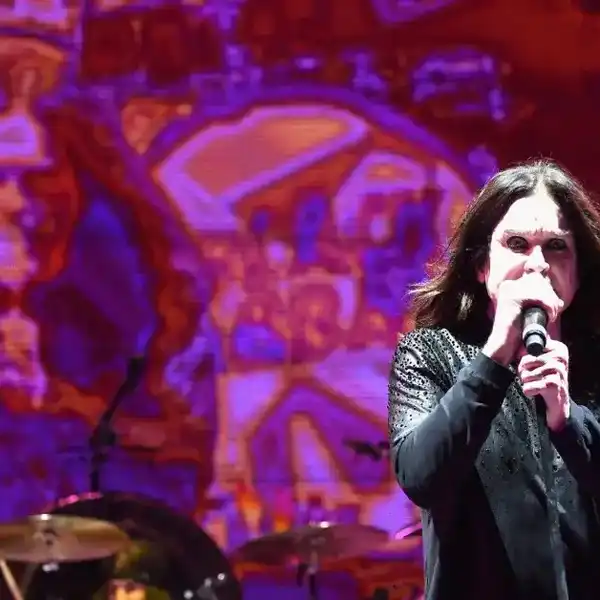

"Without Pitchfork, there will be fewer avenues for Canadian artists to reach a broad American audience," says Polaris Prize-winning musician Cadence Weapon — real name Rollie Pemberton — who received coverage from the site early in his career and began writing reviews for it as a teenager. Pemberton points to the site's immense influence as a taste-maker, particularly in the 2000s during the rise of indie rock, when a Best New Music designation from the site could make a band's career.

"When Broken Social Scene and Arcade Fire got boosted by the Pitchfork Effect in 2003 and 2004, it gave independent Canadian musicians hope," Pemberton tells Billboard Canada. "Back then, anything that wasn't on a major label was largely ignored by our own country. Getting outside attention from an American publication really added jet fuel to the Canadian music scene, bringing more credibility to Canadian music around the world. It led to Montreal being seen as the new Brooklyn."

In a blog post, Toronto punk band Fucked Up recall this period of Pitchfork's impact on Canadian artists. The post vividly describes how it felt to receive a Best New Music from the site — for Fucked Up's second LP, The Chemistry of Common Life, in 2008. The album later won the Polaris Prize, and they became a rare hardcore band to cross over into rock's mainstream.

"The score infected the room — we all knew that we couldn't barely address it, but we all knew what it meant, we had to," the post reads. "Looking back you could say that one review is why we still have a career."

Pitchfork and Breaking Into the U.S.

Founded in 1996 by Ryan Schreiber, the site has evolved in its 25-plus years. In addition to its decimal-point ratings system and emphasis on impassioned criticism (positive or negative), the site also gained a reputation as a boys' club during its 2000s run. Over the last decade, staff members like Patel have worked to expand the site's coverage and perspectives. Some have lamented the irony of the site now turning into a men's magazine vertical. (Popular music scholar Robin James explained that this decision follows a corporate wisdom where men are considered a more reliable readership by investors.)

Others have commented that Pitchfork has had less relevance since Schreiber sold it to Condé Nast in 2015. But many artists are attesting to the site's importance for their careers, even since the sale.

"Getting a thoughtful and favourable Pitchfork review for The Shape of Your Name in 2019 cracked open the door for me into the U.S., which ultimately led to American labels and my agents coming on board," says Canadian singer-songwriter Charlotte Cornfield. "I think that ultimately the changes at Pitchfork will create another barrier [to] entry for Canadian musicians when it comes to growing their careers outside of Canada."

Pemberton also attests to the site's importance for his career. "They gave a platform to the left-field outsider hip-hop I was making at a time when there were very few avenues in Canada for what I was doing. Pitchfork appreciated my work before pretty much anywhere else."

Tom McGreevy, of Toronto band Ducks Ltd., says that Pitchfork's coverage of their first EP in 2019 "shifted the horizons" of what was possible for the band. "It opened a bunch of doors and helped to connect us to the opportunities that have allowed us to make the records we've made and for those records to be heard," McGreevy explains.

American artists like Kara Jackson and Yasmin Williams have shared similar sentiments online.

A Contracting Media Landscape

The concerns extend beyond Pitchfork. Many artists, writers and music industry members see the layoffs as part of broader trends in the music and media industries.

"[This] feels like another piece in a larger winnowing away of possibility in independent music," says McGreevy. "There are fewer and fewer mechanisms that allow music that isn't mainstream to find an audience."

"I feel like most artists, especially those just starting out, or those without teams or support, don't know what to do with their work apart from throwing it into the DSP slot machine and seeing if it does something," says William Osiecki, part of Montreal duo Bas Relief and label manager for American independent label Topshelf Records.

Andrew McLeod, who releases music as Sunnsetter and performs in Zoon and Ombiigizi, agrees that it's harder for artists to plan a release campaign that will have a meaningful impact. "As an artist, even if you pay for PR and try hard as hell to market your music it simply doesn’t mean anything unless it’s picked up by the right influencers, or posted on the right forums by the right people who will actually start to spread it organically," McLeod says.

The only obvious way to make new fans, McLeod argues, is to go viral. While social media is often considered an example of the democratizing force of the internet, McGreevy adds that it's become harder to grow in a heavily corporatized online environment.

"In the phase of the internet that we're currently living through, it's much harder to create new mechanisms of any significant size that exist outside of the structures of these massively capitalized platforms like Spotify, Meta, TikTok," he explains. Major labels have the resources to mount massive social media campaigns, but for independent artists, it's challenging to break through.

What Pitchfork will look like as a GQ vertical remains unclear, but the response to Wintour's announcement indicates that artists, industry members and fans are already perceiving the restructuring as the end of a particular way of navigating the music industry.

That mode had faults, but it also helped some of the best-loved music of the last 25 years make its way out Toronto basements and Montreal warehouses to listeners around the world.