Tom Jackson Discusses His 'Almighty Voices' Series

It's not often I've engaged in philosophical exchanges during the era of Trump. It's as if the most lethal weapon we can bring to combat is utter disdain.

By Bill King

It's not often I've engaged in philosophical exchanges during the era of Trump. It's as if the most lethal weapon we can bring to combat is utter disdain. It's an impotent view of democracy as it's shredded, mangled, and dismembered in front of our eyes.

When we discovered the fascist generals of Central and South America were dropping dissidents from helicopters and executing in stadiums, we were appalled and demanded inquiries. The Vietnam War was levelling as we suffered footage of the front lines. The Iraq War witnessed the press embedded with political operatives and manipulated at every turn.

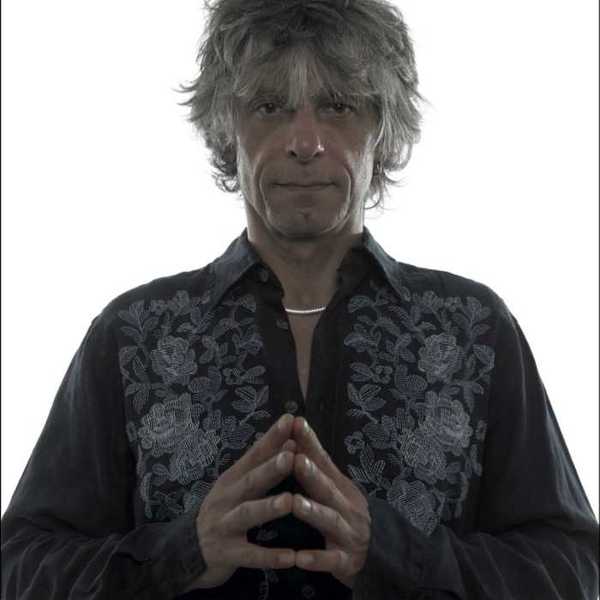

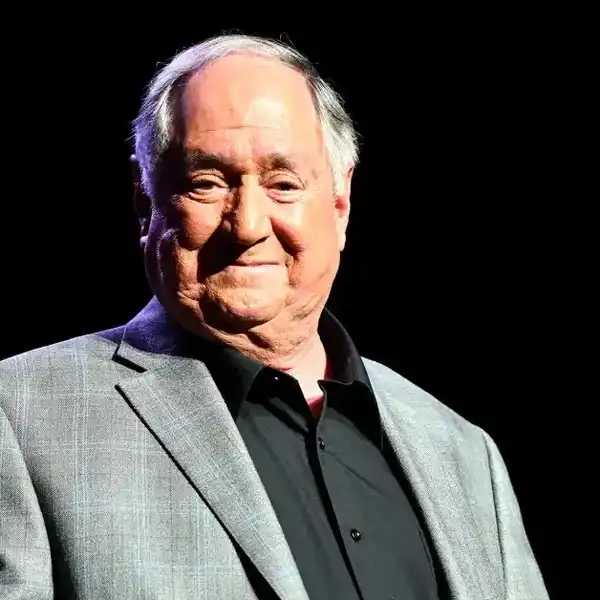

Leading up to my conversation with the much-decorated Tom Jackson – Officer of the Order of Canada 2000, Queen's Jubilee Medals 2020 and 2020, CCMA Humanitarian Award 1996, I thought to myself – what would Mr. Jackson do?

1972 I'm attending the birth of my son Jesse at Mt. Sinai Hospital. Kristine's in labour and then the news comes – it's a boy. Sitting next to me in the waiting room is actor/musician Don Francks. He recognizes me from promo photos and hearing my singles on CHUM AM. Don is wearing a cross between Indigenous styles and outdoorsman chic. A feather in the hat and rainbow colours were all there. Francks asks to draw with colour markers in the empty sketchbook occupied by one line about the birth of our son. Don filled the pages with art and colour and spread a rainbow across the pages. He also spoke of the Earth and life on a reserve in Saskatchewan and lessons learned. That moment sealed our friendship which endured for decades. Don was spiritual. He saw beneath the veneer and spoke to the better angels in our lives. I couldn't help but think about Don as Tom, and I paused and listened, talked, and observed. We are in uncharted territory. How we navigate our way is up to us.

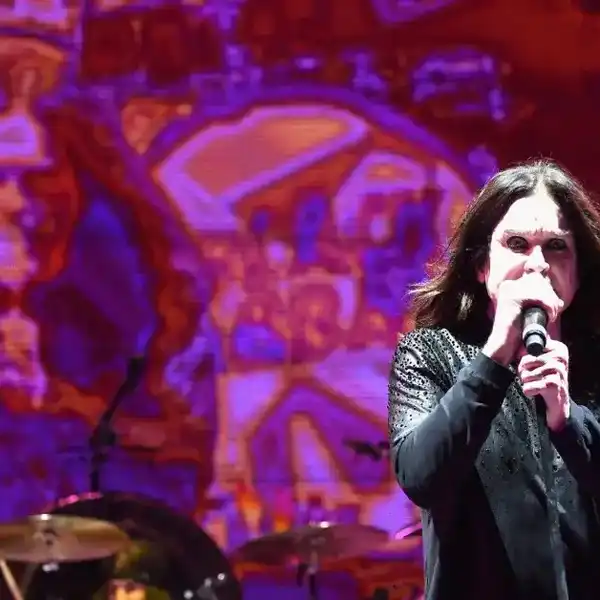

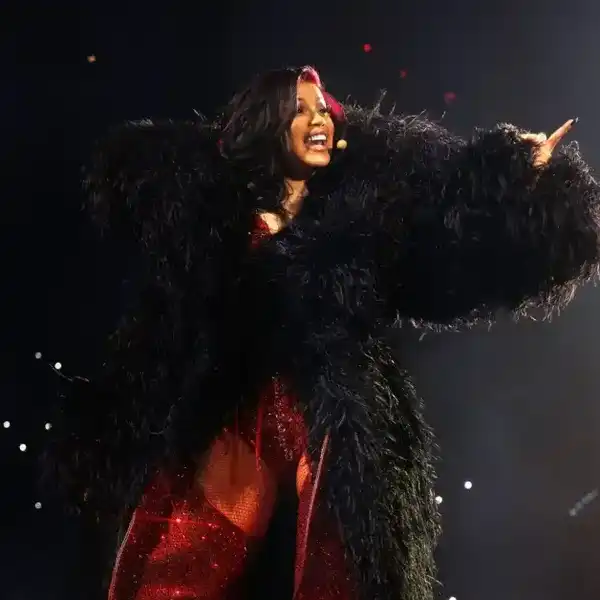

Jackson has launched a new artist-led series in Aid of Music Community Affected by Covid-19 – Almighty Voices: 12 concerts featuring Susan Aglukark, Chantal Kreviazuk, Cynthia Dale, Sarah Slean and others. We talk!

Bill King: Of great interest is Almighty Voices. What was the inspiration behind launching something like this?

Tom Jackson: When you feel helpless, you need to find a new mindset and realize that it's not about skill set. You're feeling powerless and feel like you can't do anything, and you don't know how to do something. I attribute the state of mind from where this came to the sheer weight and the force of this unprecedented circumstance; we're now in foreign territory, places that we never knew. Perhaps the other side of the dark and new reality is not something that we're familiar with.

When I was experiencing the same weight that the world was, I needed to go back to a place where I understood I could help myself, and it took me back about three decades and some. And the only thing that I could find at a time when I didn't seem to want to help myself was this prescription - a non-medical prescription, a non-chemical prescription, and that was called love. Not the word. The verb.

I found that I was able to claw my way back to the top, to the surface, by determining for myself that I simply had to change what I was thinking and help somebody. If I could help somebody else, that would change everything. I became "awake." I could breathe again. I could walk again. And ultimately, it sent me on a path that was a lot between there and here. I went back into my past vault to see what it was that allowed me to still be here on the planet. I don't know if you've ever had this circumstance, but let me just ask you. Have you almost get hit by a bus?

B.K: While biking downhill, I was forced off the road by a van of callous pranksters. I sailed above the handlebars and fell into traffic.

T.J: That tells me something. That tells me that the creator put you here to do something exceptional. Otherwise, you'd have been hit, right? So the question is, what is that really special thing? Maybe today it's defined itself to be what that is. You and I are going to create change. People are going to read this. You're going to take my words and absorb them to make them your words and send a message out to people who really, really need help. In this instance, we're talking about musicians, brothers, and sisters who are in crisis.

There is no safety net. You might think there's a safety net, but all the people that brought you joy for all of these years, including yourself, and all the people you brought joy to, have no idea what kind of circumstance you might be in. And we have to find a way to change that. We need to communicate with people so that we can help our fellow musicians, which is what this project does. There is a path right now. I was trying to figure out what the path was last night, but that way is - I'm going to communicate and call friends, I want to help support them. So I don't want them just to contribute, I want to support them. I want to pay them.

I decided to start calling friends and pass this idea around and see if people would buy into it, so to speak. And everybody said, yeah, but everybody else is doing that. You can see that. Well, no, not quite. They're not doing what this is. They're doing something similar. Or maybe I'm doing something similar to them. Am I plagiarizing as writers often do? If so, I'm plagiarizing love, which is a pretty good thing.

I decided to talk to my friends and say, hey, listen, if I could pay you $500, you could present three or four "selfies." We could put it up and find a number - a tax system to collect money for the Unison Benevolent Fund, and Unison would distribute that money to brothers and sisters - I say again, family. We're family in trouble in crisis, would that interest you? So there is a path.

I called Unison fund and talked to Jeffrey Remedios over at Universal Music and asked if he'd be interested? And he said, "absolutely." We don't know what that is exactly, but there's a support system as much as an idea germinating, which still needs to be watered and nurtured and fed, and then it needs to be harvested, cared for, and a team to watch over it. Part of that is Jeffrey, and part of that is Shelly Ambrose, who's all that the Walrus magazine is. I live outside of Calgary and talked to Paul over at the CBO Philharmonic, and he said, "Yes - what are we going to do? How are we going to do this?" I said, "We have to get it out to the universe." He said, "You present this, and we will put it into our system and put it out to 1.3 million people."

We now have a YouTube channel – Almighty Voices. And you can see the first episode if you want, Almightyvoices.ca. It's going to sit there until October the 1st. We are producing a series that will have 12 episodes, one episode a week – right up to Canada Day, and then they'll sit there until October the 1st. One episode a week, and you can watch it at any time. I'm anticipating that - I wish I had another word, but kind of like a snowball effect, you know, that it'll grow and it'll grow, and it'll grow. And if we're any good at what we do, then the sheer force and weight with which we do it will encase itself and take space in our hearts occupied right now by negative tricksters, by toxic tricksters. It's affecting our families; it's affecting our community. It's affecting us, and it's preoccupied. It's taken everything. So much of every day we think about this. We have to repopulate that space with hope - with joy.

B.K: David Suzuki said the other day, in so many words - this is the Earth reclaiming itself. Does that strike a chord with you?

T.J: I thought about that one time in the last couple of weeks because somebody had observed there's less CO2 in the air. It's a fascinating observation. Why is that? Because people aren't driving. They're not going anywhere. And the balance of nature doesn't have a conscience. It just evolves. I would say if one took that perspective that this is Mother Earth reclaiming herself, it could be misinterpreted as a sword by somebody expressing that, or it can be interpreted as a shield. I think that the shield is much more powerful in this case. Yeah, that could be true, but at the same time, we are creating a new world. This is not a revolution. This is an evolution. We need to do what we do to protect ourselves and our families and all those other things, and we have to be conscious of all of that, but at the same time, in our "situation," we become a product of something. So my challenge is, what would we do if we became a producer? What would we produce? What could we produce? What would the tools be?

If you allow yourself the freedom to repopulate that space that I was talking about, where the tricksters, the negative tricksters occupy, we can fill that up with creating health versus managing the disease; we could leap, learn, and laugh out loud. That's my prescription. What if we learned how to dance? What if we danced? What if we sweat? What if we can't forgive and forget? That happens. Go dance. Go sweat. Do things that make you feel good that affects your body and your mind. Body, mind, and spirit, that's where we're assaulted - our bodies, our minds, and our spirits. But we can fight that and can change that by creating health. Dancing, leaping, read something positive, something that is entertaining and positive - learn something.

The last time you laughed two hundred times in a day was when you were most likely two years old. Laughter is the best medicine in the world, in the universe. Leap, learn, laugh, and love. It's a big part of life.

B.K: You live a generous life. There's the fundraising and looking after people, the support of artists. Was it like this from the downbeat of your life?

T.J: I took a lot of my teachings from my parents. A lot of my DNA is based on the things that we're talking about right now. When we're at home, those are things that surround us. It seems that we often wander and leave home, and we get too far from it all. We have to come back every once in a while. Maybe that's at Christmas time or birthdays or whatever. But when you come back, doesn't it make you feel great? Those are the kinds of things that I'm talking about.

The thought of me doing something substantial, something that I was going to plant my flag and say, OK, this is what I'm going to do - it's so cliche, but I'm going to tell it anyway, I became addicted to love. I threw away the needle because this was expensive – and this a better high, and it lasts forever.

B.K: Shouldn't we live everyday as art - whether it's the music, whether it's writing, whether you're acting or whatever you're doing, it's those small things that enrich the world and have a positive effect on the person next to you?

T.J: Are you writing this down? I hope so.

B.K: To me, each person is a work of art.

T.J: I'm with you. I'm joining your tribe.

B.K: What was your world growing up? I'm thoroughly fascinated by this.

T.J: Well, for me, I don't think that my life is any more unique than anybody else's experience. You just thought the stuff was normal, right - until you start getting into, having to decide right and wrong - your life is pretty good. Then all of a sudden, "wrong" comes into your space, and you have a choice to make. Up to that point in my world, it was enriched with wonderful memories. I will give you examples.

My dad was English, and my mom was Cree. When I was born, my dad lived on the reservation with my mom in a wood-sided canvas tent with a potbellied stove. I remember jumping off old oil barrels into the slew; you know, sliding with the mud between my toes. It's just so indelible - it's just kids. We didn't have any sense of where we were other than what was presented to us by our parents. My dad was a man of peace, and my mom was very gregarious. You could figure out what parts of me fit there. But when my dad and my mom decided to move from One Arrow, which is my reservation, my nation - they decided to move to Saskatoon. My dad was going to build a house, it was late in the year, and he started digging the foundation with the spade shovel, and before you know it, it snowed, and we had to take a canvas top and put it overtop the hole with the potbelly stove, and there I was.

My dad was a brakeman with the CNR at the time, and they still had coal trains, so my sister and I would go along the track and pick up coal and that's what we used for our fuel. Do you think that was a hard time? Not a chance.

The ice truck used to come by, and we got to be friends with the guy that brought the ice wagon, and he'd take an ice pick and break off pieces and give it to my sister and me. Do you think that was a hard time? Not a chance.

B.K: What were the hard times?

T.J: If there was a hard time, it was something that I might have brought on myself.

I lived on the streets of Winnipeg for a long time, but that was a choice. Yeah, I was homeless, but that was a choice, I left home. You're at home; you stay home. You leave home; you're homeless.

B.K: That's a tough place to exist.

T.J: But I had my family there, too. I had friends, and we took care of each other, and it was entertainment, the music that led me off the street. By chance, there was a guy, Graham Jones, who was at the Indian Metis Friendship Center, he was the program director and a counsellor there. He came to me one day and said, "why don't you do something different with your life?" I said, "like, what?" He said, "I don't know." He was a musician, just like you. And I asked him if he'd teach me how to play guitar. He said, "Yes," and my life changed. I bet you have a lot of these stories.

B.K: Briefly, I was homeless the day I arrived in Greenwich Village in 1967, slept in parks and on the streets, and depended on those living on the street, for my survival. I had too much pride to call home and ask for help, but I worked it out within myself.

T.J: My mind's eye was painting a picture of musicians who just lost their gigs. I just lost everything and have absolutely nothing in terms of a means of support. So how important is this? This is a huge opportunity for us to help them help themselves and to help others.

B.K: That's the challenge.

T.J: That's it!