I Can See Canada from the Rainbow Bridge Pt. 2

In 1968, Bill King left his job as MD with Janis Joplin's band to serve ten months in a military uniform, then hitchhiked to Canada with partner Kris to find refuge from the American War. Part two of his epic story.

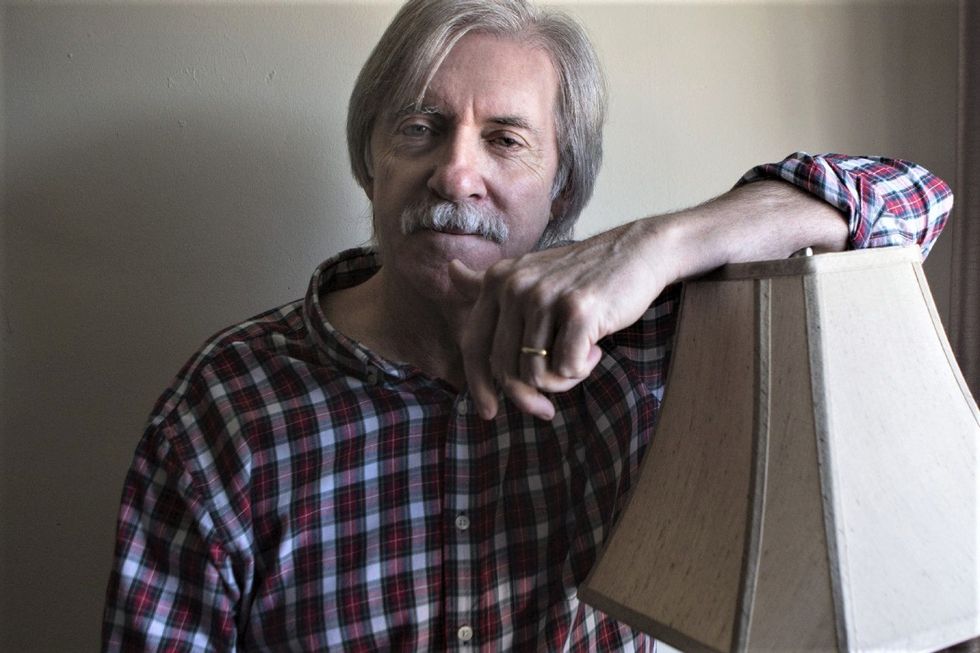

By Bill King

In 1968, Bill King left his job as MD with Janis Joplin's band to serve ten months in a military uniform, then hitchhiked to Canada with partner Kris to find refuge from the American War. "Some hated us, others cheered," he writes, but "through it all, we’ve never wavered in our resolve and willingness to address our beliefs head-on." This is the second of his epic two-part story; the first installment can be read here.

Pops was raised on a small patch of soil dividing Kentucky and Tennessee. As kids, we would straddle the imaginary line between the two states and guess which side was which.

Our early education in American history was a visit to Abraham Lincoln’s first home; a small log cabin on Knob Creek Farm in Hodgenville, Kentucky.

In 1811, the Lincolns worked thirty acres of land from when young Abe was age two and a half to eight years of age. It was here Lincoln first witnessed African Americans being transported along the old Cumberland Road to be sold as slaves, along with the birth and death of his brother.

That land connected every doorstep throughout the south, right to our ancestors' fields. While running the backwoods of my Aunt Margorie's digs in Hazel, Kentucky pops birthplace; I felt as if there were hands beneath the ground pulling me along. Each visit south was a three-day event. One locked in time and steeped in history.

Margorie Parrott Hankins could trace her and dad’s roots to South Wales, then, onto Ireland, and eventually, in the 17th century, our ancestors immigrated to Virginia, and then on to North Carolina, Kentucky, and tobacco farming. Margorie’s sister, Era, dad’s birth mother, was a tough puritan woman. You could mistake the sisters for the costume women at Black Creek Pioneer Village in Toronto who practiced life in a bygone era.

Pops said we had some Native American blood in us and even encouraged me to do some research. But I couldn’t find evidence of that. As for dad’s mom, she cared for us early on as the parents worked. I’d sit at the far end of her well-worn upright piano and listen to her sing hymns. Over time, she began to encourage me to slip my tiny fingers under hers and mimic the chordal movement.

Era passed away in 1959 from cancer. Back then, more than a few resourceful souls relied on ‘cure recipes’ from questionable medical encyclopedias over qualified professional diagnosis. It cost her dearly.

Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, was only a three-hour drive from Lincoln’s cabin and had much in common with its proximity to the Tennessee border. It wasn’t like I was entering unfamiliar territory.

On May 2, 1966, Third Army General Order 161 directed the activation of a Basic Combat Training Center at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The post was built in 1941.

Moments after my arrival I’m escorted to my new housing in the 81st Army Band; a far cry more welcoming than the intimidating atmosphere of boot camp at Ft. Knox, Ky.

The centrepiece in the main room of our barracks was a Coca-Cola machine that served up ice-cold refrigerated 12 oz. bottles of Coca-Cola at $.05 a snap. A television blaring in the background rotated between games of chance and mini soap-operas. A game of competitive pool played out like a round of musical chairs as one soldier after another took a turn at sinking the surviving eight ball. Others sat around smoking everything from Camels to Winstons; dodging the escalating temperatures outside.

I’m the new guy in motion; shaking hands and soaking up the warm reception. Then a voice from the wilderness shouts, “You’re that draft dodger, ain’t you?” I pause, then reply, “I’m a soldier like everyone in this room.” The voice responds. “No offense man, that’s cool, Sergeant Rowe says you are a celebrity of a sort. You played with all of those stars.”

There’s no way to suppress or escape your past when your history is registered and transported in your files.

First up. A meet and greet with staff Sergeant Rowe; second in command, and his band of merry men.

I assumed Rowe was well-oiled the moment I caught a view of his closely cropped, brush cut hair, swollen face, colored “heart attack red," possibly a victim of one too many forty ouncers. Rowe was all smiles as he extended a big mitt handshake. “I guess you know what your job is,” he asks. I hesitate and then respond. “Not exactly.” Rowe shuffles a few papers. “It says here of your MOS; military occupational specialty; you’re the new post pianist. That’s one coveted occupation, don’t you think?” I’m thinking how cool is this. No marching or concert band, a few gigs here and there, then back to civilian life.

“So, what does the post pianist do,” I ask. “Whatever the man in charge decides.” The man in charge happens to be Chief Warrant Officer “Iggy” Ignacio, from Honolulu, Hawaii, a former bandmaster at the Naval School of Music, and one shrewd/cunning survivor. “He’ll see you now,” says Rowe.

On the first meet, Ignacio lays the “hard-ass” no-nonsense bullshit talk on me, then asks. “Have you ever played for bigwigs?” I tell him there have been plenty. “If you keep your nose clean, you’ll be playing in the homes of the most important people on this base; generals, colonels and majors, and all I have to say to you is, don’t fuck up.”

Minutes in, Ignacio pauses, then looks directly at me, “get rid of those civilian glasses and switch to army issue. You hear me?”

I wore aviator glasses all through basic training and drew a fair amount of grief for doing so. It was my only physical connection with my diminished rebel self.

I’d be ordered to a post optometrist to have eyes examined, and within a week or so, a new pair of geeky looking glasses would arrive. It did nothing to enhance my look. My best defense, “sir, the prescription is fucked up. Can’t even see my hands.” This scenario played out the entire time I was in the military. Ignacio would catch a glimpse of me coming and going and yell “Kingggggggg,” and his bellowing howl would rattle the building. I’d be herded in and then interrogated. “Didn’t I tell you to change those glasses? Are you ignoring me, soldier?” I eventually won this stand-off.

I kept in mind the role television played in stoking the flames of animosity. We watched actress Lucille Ball from the ‘day room’ mock those with a few days of hair growth and perform some mindless skit about hippies. Vice president Spiro Agnew stamped us the enemy of America, subversives, every moment he sucked up screen time. Not far behind, evangelical Christians took the lead in condemning and playing the patriot card. A far different mindset than the antiwar Catholics. Life was unreasonably complicated. You were either a draft dodger, unrepentant radical, or possibly a commie. Whatever the case you were punched, spat on, denied your rights, and aggressively confronted by those who viewed you a troublemaker.

Down south, men were men; some ‘good ole boys.’ Others; children born of neighbors; uncles and aunts; others dirt poor, who spent hours collecting hubcaps, snoozing in lawn chairs, locked to the bleachers of a ball diamond, lost in a backroom card game, or inside a pick-up truck cramped with gun-toting crazies planning to shoot something for fun. Men were simple with desires as basic as the contents of a can of soup, and easy prey for “flim-flam” politicians. Most just liked to hear someone say they looked good, and to be recognized as being the bread-winner in the household.

The unpopular war was all-consuming and an affront to the poverty-stricken masses hidden in the hills near the coal mines. There were plenty places to hide out. No need to look north to Canada or across the Atlantic to Sweden when you could hide in the backwoods of Arkansas, Kentucky, Georgia, or Tennessee under the protective eye of a close-knit family.

After settling in and being assigned a bunk, room, and locker, I began meeting my fellow bandmates. One who called himself “Gettier,” from San Diego, took an interest in me. Steve played trumpet and was sitting out his last days hanging with the concert band until wholly processed and released. Steve spent a year in Vietnam.

You want to know about war, what it was like on the ground and all around, just hang with someone only days back from the theatre of war.

Gettier was somewhat crazy. Sometimes in a good way, and at others in need of psychiatric assistance. He hated Ignacio – called him “pineapple.” At first, I thought he meant that as a term of affection but decades later when we re-connected on Facebook, I surmised he was an avowed racist who had a terrible habit of calling the Obamas “monkeys.” That’s when the block feature came in handy.

Gettier took me everywhere. He’d laugh insanely whenever the urge was impossible to contain. He played trumpet and talked Miles Davis, but he was more of a fan than player. Gettier also spoke endlessly of his own experiences in Vietnam where he found himself in perpetual conflict with his commanding officers. For a brief period, he was a driver for those designing offensive strategies and was there to escort them from place to place. After being shot at he managed to purposely ingratiate himself with everyone and was then unceremoniously dropped in rice patties or tall grass for up to six weeks at a time with a collection of paperback books, a rifle, supplies and surrounded by fields of “get high” pot. Gettier saw the war mostly stoned. He was also a Kung Fu student that became a lifelong passion.

My closest pal, was draftee Ron Sullivan, a high school teacher from Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. Ron played sax and had a monster sense of humour and high intellect. We talked a bit of music, but the heart of our conversations were about current affairs: Lyndon Johnson, Kissinger, Nixon and, the most pressing issue – war!

Ron and I theorized how and when the end game would be played out. Would the North Vietnamese come to the table and engage and trust Kissinger and call it quits, or would the war carry on another decade or so? We’d heard rumors of peace treaties in play, yet we recognized the manipulative games politicians practice for political gain.

The politics of war is very much a sinister chess game and, for most, ends in a stalemate. An uninformed public follows orders. Playing with the lives of the very poor, the draftees and committed men and women in uniform was, from where we stood, a privately negotiated scam between the well-heeled and the well-connected. Ron and I, and those around us with life experience and acquired knowledge of the charade debated the course we should take to protect our own lives.

We knew the politicians serving in Washington and throughout the country, in statehouses, and on Capitol Hill could easily protect a son or relative and place a call to someone connected up the food chain and have them either assigned a sweet desk job in Germany or deleted from the draft. Big money deferments were the game.

Vietnam was a numbers game. General Westmoreland, who commanded American forces in Vietnam from 1964-1968, talked bodies – body count. It was as if there was this neon scoreboard tabulating death that played out every day, designed for news-hungry Americans. There was always this confusion about whether we were fighting to discourage the Vietnamese from surfacing in America and turning Rhode Island into a communist foothold or purposely choose to blaze a killing path through Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam to scare the Chinese.

One fellow I grew to know was an administrative assistant for our company commander who recalled his times in Vietnam to me. He said there were nine army bands deployed. Much of his duty time was spent hanging out cleaning his rifle, burying bodies, and fighting off a variety of jungle induced diseases. A good portion of time was spent getting high. The sergeant was living with a wound that wouldn’t heal. No matter the treatment; it leaked a pus-like substance.

Every month we’d rotate house-keeping duty, and part of that deal was mopping and waxing the front offices. I’m swabbing and sloshing near the gentlemen’s desk and happen to notice a trash can loaded with discarded Benylin containers. Only, inches from the receptacle, I slide open a drawer and observe a collection of thirty or more capped bottles of codeine cough syrup. This guy was hurting! He went on to say he’d served in a unit that was sent ahead of doctors and nurses under the guise of inoculating villagers from diseases.

When marching, the band was arranged with clarinets up front, saxophones, then trumpets, heavy brass; and far behind, percussion. The band would march in playing patriotic songs when, unexpectedly, all hell would break loose. Occasionally, the front line would be ambushed, leaving the clarinetists and others up front either dead or injured. He pretty much explained it as if it was like a scene out of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 movie, Apocalypse Now. Our band was connected to the 101st Calvary Airborne Division, and they expected results. More bodies to count.

The next while, music became my focus. I played private parties, slapped brass cymbals together in marching and concert band and copped a rare few paying gigs off the post. Near the end of my stay, it was revealed I played clarinet, an instrument I excelled at in high school – one on which I collected numerous awards in state and regional competitions. I purposely hid the fact, knowing I’d be called on to march; something I did with less skill than a man with two broken legs. When word leaked out, Ignacio listened and then awarded me the first chair within striking distance of his baton. The consolation prize? Playing the same arrangements of the Sound of Music I played in high school.

Outside the front gates was a long row of pawn shops and shady drinking holes. This was where Jimi Hendrix and bassist Bill Cobb jammed. Hendrix was part of the 101st Airborne Division and, from what was said on base, injured himself during a parachute jump. Hendrix supposedly snapped an ankle and was let go. The records say otherwise. Hendrix was forced to serve and was mostly incorrigible and then released. Hendrix’s played the row of bars and was a local favourite. He also left a trail of women awaiting his return.

There was a lifer; an older Afro-American named Frank who liked to talk jazz and blues with me. Frank played the bars and brought me in to play organ on occasion. He was comfortable with the routine and secure in his job with the military and staying until retirement. There was a lot of Lou Donaldson, the Crusaders, and old rhythm & blues in the set list. “Honky-Tonk” and “Kansas City”; crowd favorites.

On one occasion, I’m hanging near the front door chatting with this seemingly nine-foot-tall bouncer sporting a cowboy hat and menacing scowl. Moments pass before this brush-cut paratrooper blows past without showing ID. The legal age for drinking was still 21. Then the big guy shouts him down. The two converge in front of a table thick with empty beer bottles. Words were exchanged when, suddenly, the trooper takes a swipe at the big guy. In one move “big guy” picks him up and drops him on his head and stomps dead centre of the guy’s chest. Out cold! He then throws him over his right shoulder, carries him outside and tosses on a pile of gravel near a row of motorcycles. When the guy comes too, he then jumps a bike, accelerates into on-coming traffic and is hit dead-on, then thrown violently from the road. Dead by intoxication and miscalculation.

The Day Kristine Arrives, May 12, 1969!

It’s been near impossible to write this chapter. A beautiful woman; tanned, with blue eyes shining Kentucky sunlight with long hanging blond hair; lands in the middle of thousands of sex-starved men. This could be the makings of a World War 111, or maybe an Italian cinema classic.

Kristine arrives with intentions to stay. In fact, her appearance was so overwhelming the guy who drove us back from the airport refused to make full eye contact. Kristine and I had an agreement. Give it one year and see where this relationship finds itself.

Once on base, a posse of soldiers gather and follow her wherever she strides. From post library to PX. The best thing about this scenario, Kristine knew how to control and entertain the men, keeping them off guard and on good behavior. Soon after, they became protective of her. Most had never met a woman as liberated; one from New York who spoke frankly of anything that came to mind and would talk directly to them without being patronizing or demeaning. She would soon become one of the boys!

As the weeks and months pass Kristine assumed a position beyond rank. She was invited everywhere and expected to show. Southern women took a back seat to their spouses and usually agreed with whatever the man coughed up. Not Kristine! There was no debating her views on the Vietnam War. When you went face to face with her in those encounters; you’d better come equipped with answers.

You could sense it was a prelude to a long hot summer and Kristine and I were invited to share apartment #103 at 507 Greenwood Avenue in Clarksville, Tennessee with Gettier. At first, we occupied a cot stuffed in a far corner of a room where Kristine and I wildly entertained ourselves until Gettier offered to swap his bed for the cot. Our schedules were as such that Kristine and I would spend as many hours together as we could squeeze from a day.

I had PX (post exchange) privileges and could purchase most supplies at a discount. In that PX was the best collection of vinyl recordings, and up to date, I’d witnessed since robbing Tower Records in San Francisco of nearly every monaural, Blue Note jazz side. I bought a copy of Crosby, Stills and Nash, Blood Sweat and Tears, jazz man Gary Bartz, “Libra,” Richard Harris – McArthur’s Park – Kris brought several well-played Laura Nyro sides, a Jefferson Airplane record, The Temptations, Smokey Robinson and then the sounds roared.

The rustic house was shared with an odd group of servicemen who stayed mostly out of sight with their girl-friends. We had the upstairs mostly to ourselves. The walls were wall-papered in a floral design of vines and fading greens, extending from floor to ceiling. The bed? A wrought iron implement of torture. The room? Expansive, sunny, and inviting and just beyond the nearest window; trees thick with the leaves of summer, shading the sounds of children’s laughter from a nearby schoolyard.

The weeks played out as Kristine accompanied me to every solo gig, most army functions, and even the most mundane military assignments.

Ignacio never missed an opportunity to send me anywhere he could score points. He was pushing for the rank of Chief Warrant Officer. Most of my evenings were reserved for army functions and a good portion without pay. Living off post, Kristine and I struggled with rent and food costs, and any dollars earned from gigging made the effort sustainable.

I was ordered to join the post-theatrical production of “A Funny Thing Happen on the Way to the Forum.” I’d never worked on a musical before and suddenly found myself trapped five nights a week in rehearsal. Kristine hung near the piano. I had already decided I was going to marry her, so I began a charismatic drop to one knee in the aisle and proposing. Kristine played along and reminded me we were taking a year to consider. Late May, I informed my unit I was marrying Kristine. I made the decision solo. Word got back to Kristine, and I was exposed. She did say yes! On June 30th, 1969 we were married at my parent’s home in Jeffersonville, Indiana.

Independence Day rolls around, July 4, 1969, when a knock comes at my parent’s door. While celebrating five days of marriage, a military officer inquires of my whereabouts and then passes an envelope masking orders for Vietnam. This was a sober, heart-wrenching reversal of emotions. My feelings towards war, especially this war hadn’t changed. The both of us were set in our opinions and learned much about the so-called enemy; the Vietnamese people, and took offense when we heard others call them “gooks” and “slant-eyes.” Kristine looks at me and immediately says, “let’s go to Canada.”

I thought back to the Thursday afternoons I played piano at the veteran’s hospital. It was there I had my first-hand experience with the casualties of the Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon fiasco. Men arrived in gowns; many missing limbs, others hooked up to IV machines, while others were focused on some distant thought. I walked the back lanes in the recovery barracks, where those who were thought to be untreatable lay for weeks and months in isolation. I’d play whatever was requested and listen to their experiences. This was where truth and reality intersected.

Kristine and I begin investigating other options - from “conscientious objector status” to “compassionate reassignment.” We applied through the right channels and were first interviewed by the post chaplain, then worked our way up the chain of command. All efforts were rebuffed. Meanwhile, there was no let up from Ignacio. The extra duty continued to flow, as my rank grew. I went from private 1st class on arrival to Specialist 4th grade in six months. Ignacio assured me I’d make Specialist E-5 on arrival in Vietnam.

The next two months Kristine and I hitchhiked far away from the base. We’d journey the back roads and towns of the south and engage the most interesting folks. Hitchhiking for us was much like summoning a taxi. Kristine would stand roadside with her thumb out, me, mostly out of sight. A car would stop, and Kristine would climb half in then ask whoever was steering to wait, and say, “my husband is just behind me.” Hilarious, but it worked.

I’d been awarded a three-day pass, so Kristine and I decide to visit Aunt Margorie, now married for the first time at age 63 to a blind man, 70 years of age. Margorie moves in with him in the small southern hamlet of Dresden, Tennessee; only eighty-three miles south of Clarksville, Tennessee.

Hitchhiking was a breeze. We caught a ride with a lovely woman decked in a sunbonnet who pleaded with us not to rob her. We agreed and laughed our way further south. The two of us were never prepared for the occasional hour or two between rides; never bringing water or wearing hats to protect us from the blazing, suffocating heat.

Marjorie bore the same stylized look I remember from my youth. She was polite and reserved.

Kristine and I first ‘quick-walk’ through town and observed everything is closed; then return. After a short chat around a kitchen table, and walk around the backyard frog pond, Marjorie feeds the two of us and orders us to bed – at 7 p.m. The same hours her and her partner kept. That bed was covered in plastic with only a sheet on top. The room, a boiling, stifling, vacuum. No air, no sound other than the movement of the two of us twisting one way or another atop crackling plastic. And yes, we had to pinch the lips of one other to choke-off the laughter. Next morning, Margorie mentions she had a difficult time sleeping with all that ruckus in the adjacent room.

The trip back was classic.

The backroad was barren of traffic. The sun a hideous, murderous constant. Then I spot something coming up the road partially hidden in a heat-spewing asphalt mirage. A duo-tone, blue and white 1958 Ford sedan.

As the car slows, I can see the driver’s side; the brim of a straw hat, the frame of an older man draped in denim overalls, suspenders strapped down to his waist. Next to him, a young woman. The closer they get I can make the outline of what looks like a boy of 12 years sitting tall in the back seat.

“Were you folks going?” she asks in a cordial tone. “Heading back to Clarksville, Tennessee and Ft. Campbell.” The woman looks up at us and says, “you all can sit backside with my children if you want. It’s plenty cramped back there”. This is when we spot three or four smaller beings. “I’m sure we can get you ‘a ways’ up the road.”

This was a classic!

As the tires slowly spin, she informs us her new husband was nearing 70 years of age, and they were in route to lay a reef at the grave of a dead son in Paducah, Kentucky. This was ‘Grapes of Wrath’ poor.

Kristine carried on a one-sided conversation with the older boy, sitting dead centre of a spare tire, and who could barely shape an intelligible response. The grieving woman went on to describe her hardships and recent marriage to this ‘good man.’ As I shuffle about in discomfort and lean forward, I catch a glimpse of her newborn. The sweet face was covered in flies exposing a series of bites across its forehead.

The old fellow never pushed the speedometer past twenty-miles an hour making the trip an excruciating affair. An hour or so in, we spotted a sign stating the mileage distance to Kentucky Lake and held tight. Eventually, the tree-lined roads gave way exposing the large body of water. Covered in sweat, grime and short on fresh air, we asked to be dropped at the side of the road. Seconds after waving goodbye the two of us sprint into the lake, clothes and all. Baptism and rebirth.

The Journey

Those officers I got to know from hanging out at nights with, filled me in on what to expect once in Vietnam. United in their opinion; they vowed never to return and swore they would leave the army first. They saw the war much the same as us, as a political struggle and us as pawns of corporate interests. They had encountered and known the Vietnamese first hand and found them humble, mostly an agrarian society; giving and most forgiving. They understood the U.S. had a long history of overthrowing governments they deemed hostile to its interests, and would not hesitate to assassinate a head of state or obliterate a nation that refused to abide.

September arrives, and I’m to be released for a month-long vacation and time to get matters in order, but Ignacio won’t sign papers releasing me from post duties. In fact, he robs me of a two-week vacation while trying to score more points, sending me on more bullshit gigs. I decide to file charges against him with the post Adjacent General. The two of us were interviewed, and I won my case and was gone by September 16, 1969. I also walk away with a Letter of Accommodation from the army in recognition of superior performance and service to my post.

Back in Indiana, we unload our possessions. Then spend time visiting friends and catch a bit of jazz. We pack what we need and plan the days ahead. Before exiting Louisville, Kentucky and on to Erie, Pennsylvania; we caught the Count Basie Orchestra on the 21st of September at Club 118 on Washington Street near the river. Music of this caliber was hard to come by in the military.

While in Erie, we visit both Kristine’s great-grandmother and grandmother then fly on to Manhattan and stay at the cockroach infested, Hotel Earle.

October 12th, we leave Manhattan for Fort Dix, New Jersey; me, committed to a year’s service in Vietnam. We board a train from Long Island to Manhattan then hitchhike on to New Jersey. Just beyond the front gates of Ft. Dix, we hail a taxi. It just so happens it’s the day 10, 000 antiwar protesters gather to protest the war and encourage soldiers like me to refuse Vietnam. This was the biggest moratorium against the war, and Kris and I had to navigate our way through the unruly crowd.

We momentarily pause at a military police booth where I’m questioned and then threatened. I sported two weeks growth of sideburns that somehow offended one officer who demands I shave. He then warns if he sees me again he will administer a beating on me. Bizarre, but true.

We drive on. Next up Kristine and I are again waved off the main road by a military police cruiser as we close in on my designated area. Again, I’m threatened with violence. I lose it and tell the man, “I’m being sent to die in some foreign land to possibly die, and you want to physically harm me over sideburns?” He then lets us go.

I make my way to orientation along with two hundred other soldiers all destined for Vietnam. A 1st lieutenant delivers the bad news. It’s been decided we are to be separated from our spouses and transported to the other side of the base and held until being flown to San Francisco, and on to Vietnam. Protestors had breached the secured gates and were now fanning out and running through the weeds and down side streets screaming for an end to war.

I can’t express the sickness that overcame me. It was comparable to the ride with the FBI agent to the courthouse in New Albany, Indiana. The body trembles, and the heart nearly cease as a wave of depression stills me. I could visualize what saying goodbye to Kristine was like, then never returning. A life wasted in a bullshit war. It’s then I decide to barter with the man in charge.

I approach and tell him I’d just married the young woman outside, and I really can’t get my head around saying goodbye and need a night to work this out. He could read my tears and then responds. “I’ll give you a pass for a night at a post guest house, but if fully occupied, I expect you back here.” I take the offer and rejoin Kristine and head towards the accommodations.

As we turn a corner near a military barracks, we are confronted by a platoon of returning veterans dressed in battle fatigues and sporting beards. A guy spots me and shouts – “hey asshole, you going to Vietnam”? Confused by the question, I watch him turn to his pals. He then yells, “you’re a fucking moron if you go.” The group looks away then slinks around the corner engrossed in laughter.

Kristine and I arrive at the post guest house and find it fully occupied. We now need to deal with this. Kristine asks, “what are we going to do?” In what would become the biggest decision of our lives, I pause then say, “we are doing what you suggested months back, going to Canada.” Done!

We returned to the orientation centre, place all my military apparel on a bunk. Grab a T-shirt, pants, and shoes and begin looking for a clear path off the post. We stride near tree-lined lanes leading toward the gates. On the horizon, I spot a military cruiser heading our way. We dash from the road and lay flat down in the tall weeds. Once clear, Kristine makes an appearance, like she has done so many times before, and begins thumbing a ride. Not long after, a car pulls up. Kristine explains what we are about to do to a young man who looked as if he was full-blown military. He tells us to climb into the back seat and hide beneath a blanket on the floor and he would smuggle us out the front gate.

During the exchange of conversation, he informs us he’s a son of a military officer and against the war. He easily breezes out the gates, past the military police, down the main highway to the first gas station in range. I change into civilian clothes and banish the last remnants of military apparel in a men’s room.

Close by, we spot a long-haired couple. Both, had been protesting outside the gates and ask us, “where are were going?" The answer? Canada, but first, New York City and our best friends Bob and Barbara. “Well, get in," he says.

We call ahead, and Bob informs us he has the best Lebanese hash known to man and once we arrive we are all getting stoned. I’d never smoked hash before, and Bob made it sound like cause for celebration, and most inviting.

We smoked up and got seriously stoned, ate some amazing soul food, laughed, and celebrated, then early next morning Kristine and I begin our journey to Canada.

We made our way to the Triborough Bridge in Brooklyn and did what we’ve always done; hitchhike. It was only minutes before a motorcycle-policemen intercepts and questions us, then cautions he’d arrest us if he caught us hitchhiking anywhere near the bridge.

Somehow, we were able to flag down what looked like a milk truck. It just happened to be a delivery truck loaded with sauerkraut. I sat below on the floorboards – Kristine high above on containers. The driver spoke few words, yet drives us to White Plains, New York and drops us on a side road.

A fair amount of time passes before we flag-down, “Mr. Straight”. A clean-cut gentleman invites us in and announces he was on his way to Springfield, Massachusetts, and the baseball hall of fame. Throughout the next few hours, he attempts to pull information from us. We resist and reveal little of our intentions. The two of us compromise and talk baseball – Ruth, Maris, Mays, and Mantle; the greats enshrined in the hallowed hall.

Not far outside Rochester, New York the guy drops us at the Rochester turn off in a heavy drizzle. We weren’t prepared for the change in temperatures and secured protective cover under an overpass and wait for the next ride.

This was no easy feat. An hour or two passes before an elderly gentleman wearing a tweed overcoat and brim hat pulls over and speaks with us. He questioned our purpose for being here and let it be known he wasn’t about to pick us up. He also wanted assurance we weren’t going to rob him. He then relents, invites us in, but seems uncomfortable with the gesture and quickly changes his mind and drops us near an off-ramp, not far from where we began. Then insists we exit the car.

With darkness approaching and no break in the unrelenting downpour, we decide to walk up an off ramp away from the highway. It was here we are intercepted by a state trooper, who then grills us about being stranded alone late at night and warned us to stay off the highway.

Parked on a side street, and not far from the off-ramp, stood a parked car with two occupants. Kristine walks up and taps a window and asks if the driver was going anywhere near the Canadian border. The couple says, “why not”? It seems the two had been living in the car and welcomed the diversion. They were in need of gas money.

The guy was a fair bit older, hair slicked back and with an edge to him, while the girl seemed to be in her mid-teens. Both could talk a streak.

With the gas tank filled, he agreed to drive us to Toronto. As we drew closer to the border we never felt threatened, but there was something about the guy that said he was more connected to the car than any outside address. He told us he had been to Toronto once and like the big city. The young girl, I doubt, had ever ventured beyond a few surrounding neighborhoods.

The Border

This was heart-pumping scary.

I knew once we began crossing Niagara Falls it was either no turning back or five years in prison. Customs and immigration loomed up ahead.

After stating our intentions to enter Canada to customs officers, we were waved aside and asked to wait in a holding area. The first to be questioned was our driver and his young companion.

Immigration separates the two. After they interrogate the guy he returns and approaches Kristine and asks if she had extra ID. Kristine had a photo of herself with dark hair of which she shows him. He grabs, says thanks, and hands to the girl. Next up, the girl.

The young one disappears and quickly returns. Then it’s Kristine and me.

We show ID and express our intent to visit Toronto and the fact I’ve been there before as a music student and want to show my new bride what a great place it is. All is quiet.

Next move. Border police arrive from New York State, cuff the guy and rescue the girl. Nothing is said to either Kris and I. The next three hours we sit in silence awaiting a verdict. That’s when I decide to make a play and approach the counter. Behind is a uniformed officer.

“Sir, what happened to the guy and girl who drove us here, “I ask. The officer says,” they are being transported back to New York. If you have any property with them, you should go now and retrieve.” Our only possessions were a few clothes and a Sony tape recorder.

After collecting our few items, I then ask. “What did they do?” He pauses, then says, “he’s a parole violator and she’s fourteen years of age – a minor.” My eyes drop, the heart sinks and beats double its allotted needs. Then a moment of clarity. “Sir, we didn’t know those people. They just gave us a ride.” Once again he pauses, then asks, “What are you doing here?” I then knew I had one shot at this. “Kristine and I were recently married and haven’t had a honeymoon yet, and we thought Niagara Falls was the most exciting trip we could afford. I’d been here with my parents, but Kristine has never seen the Canadian side of the falls”. He then abandons his position at the front desk and disappears.

Moments pass, when he returns and signals me down front and says, “We have no criminal record of you two; so, I’m assuming you’ve committed no crimes, and I see no reason to hold you here; but first, where are you staying in Niagara Falls? I look out a side window and point to a motel up the hill, the Rainbow Inn. “The Rainbow Inn, sir!” He smiles and says, “well you too young folks have a great time and remember you can only stay a short while in Canada. You understand”?

I can’t remember a time in my life like this. Kristine and I holed up a sleazy border-town motel, secure in a vibrating bed; a room resplendent in orange drapes, a blinking tv, and a shag carpet. And then the capper, Kristine pulls out a matchbox packed with some fine weed. Welcome to Canada!

On numerous occasions I’ve been questioned about our decision to leave the war and America in the rear-view mirror. Some hated us, others cheered. We were first abandoned by family, then loved. Through it all, we’ve never wavered in our resolve and willingness to address our beliefs head-on.

Any doubts about that decision were eradicated in 2002 when Kristine and I were invited to share a momentous occasion with the Napalm Girl in the epoch photo – Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the subject of the Pulitzer Prize-winning capture by Nick Ut; taken at Trang Bang, South Vietnam June 8, 1972. It was a World Press Photo event and Phuc the featured speaker. Phuc spoke of her ‘skin on fire’, the numerous crafts, operations; the unrelenting pain and her survival. And like us, she chose Canada her permanent home.

Kristine and I clutched hands throughout Phuc’s retelling of that horrific day and the courage to stand up against war and most of all, the well of forgiveness inside her. We were invited to meet and shake hands and relate our feelings. As Kristine and I clung to each other we attempt to subdue the uncontrollable flow of tears.

We sensed all the good Gods in heaven were present. Phuc was just one of the millions of children war has burned and disposed of through our times. Knowing I’d never pointed a firearm at another, or placed a child’s life in jeopardy, torched a village, or murdered the innocent was reassurance there are other ways to confront evil. Kristine and I were free to serve in our new country and give back in a way that will have a lasting effect.

A year or so later I wrote these lyrics:

“Oh, it always snows on the nicest of days there. A warm afternoon is something to live for, as the fire burns in the second stage of my life.

“People have talked of far away places, but none seem as close as my home in the spaces, I long to be, where my friends still wait up for me.”

“Canada, it’s been a hard-fought battle, and I long to be your friend. May we find happiness in your silent pride. May there be justice for those who live and die. Thank you for saving me and giving me a place to live.”

Amen!

+Canada – "Goodbye Superdad" – Capitol Records.