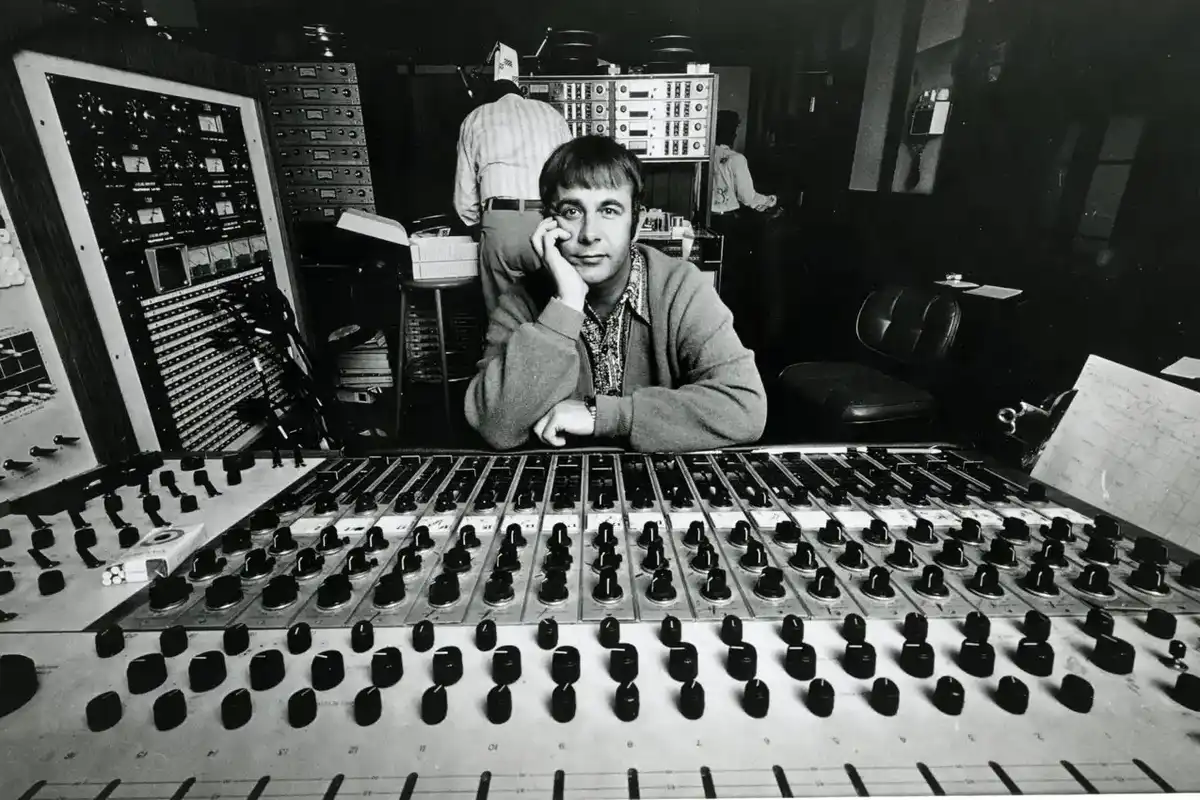

The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever - A 1992 Interview With Drummer Max Roach

He developed and shaped the very essence of jazz and the role of the drummer, and was onstage at Massey Hall for a star-studded concert termed the greatest ever. From the archives, here is an illuminating interview with Max Roach.

By Bill King

The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever - Massey Hall - May 15, 1953.

Max Roach personifies jazz music. From his early accomplishments as a leader, drummer, and composer for a variety of bands with Clifford Brown, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie to his later theatre, film, TV and orchestral work, Roach continued to develop and shape the very essence of jazz and the role of the drummer. Along with performing, composing, arranging and recording, he was a professor in the Department of Music and Dance at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. This interview took place in 1992. Roach passed away August 2007.

There is much debate between those who were there and those who said they were. Max actually played that night!

Here he talks about his music, the players and that grand night at Massey Hall.

“When we did the historic concert with Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Dizzy Gillespie, Mingus and me at Massey Hall in Toronto, Mingus was the one who brought the engineer and tapes up there. Mingus and I put together a company called Debut and brought the engineer up, but we had to do it silently. Bird was signed with Norman Granz. The first record we put out on our label we couldn’t use Charlie Parker’s name on it. We called him Charlie Chan. Later on, we made deals with other people and it was released another way. You have to create your own opportunities.”

BK: Jazz was born on the wrong side of the tracks, yet it has triumphed over all obstacles from its unpretentious birth and rejection by its homeland. Do you see a change in the nation’s attitude towards the idiom?

Max: Yes! I have a lot of respect for guys like George Wein and Norman Granz. They were able to take this music out of the club scene and put it on the concert stage around the world. Jazz at The Philharmonic was the first, of course. We started working in concert halls around the world. George Wein has been able to continue it with his JVC and Newport Festivals among other things.

It’s a team effort that takes everybody, producers, entrepreneurs, public relations, and so on. You need one of those Drink Milk or Take Tea campaigns. Recording companies, musicians, and entrepreneurs are starting to realize, if we don’t get into this thing together none of us is going to make money from it. That’s what they call the bottom line. They ask you what’s your track record, and that’s how they ascertain how much money they’re going to invest in you. “Listen, you only sold 10,000 records last year. You made the nut, but we can’t invest any more than we gave you last year. You can’t make any moves upward until you exceed those numbers.”

You can do experimental things like To the Max, but it costs a lot of personal money. Thank god I got that MacArthur grant. It helped me do a little bit more. If I have an idea, I’ll take it into the studio myself. With a record company like Mesa/Bluemoon, I know they’ll usually support it and invest some money in the recording expenses.

BK: Education plays a leading role in bringing a greater understanding of the art form. For many young musicians there needs to be a clearly defined entry into o the jazz field. What kind of organizations can offer this service?

Max: We now have the International Association of Jazz Educators. When we met in Washington D.C. early last January, there were over 2,000 people who were involved in jazz. Musicians even came from Russia. The International Association of Jazz Educators is made up of professors and teachers from colleges and universities around the world. Many are here in the U.S.

For example, I’m with the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in the department of music and dance. We offer a bachelor’s degree in music with a heavy concentration of jazz. The New England Conservatory offers a master’s degree. That’s just two. There are now many ways to get an education.

In my opinion, it’s much healthier than the way Charlie Parker and all of us who came up through that 52nd Street scene, on the other side of the tracks, as you put it. We had to play in an environment where there were terrible instruments, pianos out of tune, and places crawling with all kinds of underworld activities. You were working in places where alcohol was the staple for keeping the place alive and drugs were everywhere. You couldn’t really blame the club owner; he was just trying to keep his thing alive.

You can get caught up in those kinds of things; it’s not a healthy atmosphere to survive in. I look at Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, all these great people. Monk, and the whole crowd; they all gave us something of great beauty in spite of the conditions they had to work in. That environment still exists.

We listened and practised on the gig but lost many a person who got hooked up with the environment; Fats Navarro, Bud Powell, and before them, Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday. All these kinds of things were working against us. These folks gave us things of great beauty in spite of the situations they found themselves in, but now we have a clean environment on the campuses. The best example of that is the group of young lions headed by the Marsalis crowd. They are doing some marvelous things.

BK: Some fear if jazz isn’t constantly moving forward it will stagnate and lose its purpose. Is this a legitimate fear?

Max: No, I’ll tell you why. This music, contrary to the music of other cultures, is very fluid. Even though we have a Louis Armstrong, it doesn’t stop there; we have a Roy Eldridge, it doesn’t stop there; we have a Dizzy Gillespie, it doesn’t stop there; we have a Miles Davis, and it doesn’t stop there; we have a Wynton Marsalis. Every generation is allowed the luxury as long as they are within that continuum to add to what’s going on. The only difference between John Coltrane, Lester Young, and Coleman Hawkins is the individuality. They all approach it with the kind of virtuosity and creativeness with the continuum of the music itself. So, this is fluid, and it’s not the kind of musical culture that stands on ceremony.

I know at the University of Massachusetts, where I’m teaching, some of the finest classical composers are teaching some of the finest classical composers are teaching because they can’t get their work played on stage because concert halls and orchestras constantly play baroque, Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart. They can’t get a word in edgewise. Louis Armstrong, God bless him, will always be here, but it doesn’t prevent us from having a young Roy Hargrove. Our music gives each generation an opportunity to say their piece.

BK: Jo Jones and Sid Catlett are swing drummers most frequently cited as influences on the bop generation. What did Jones and Catlett do to inspire you and Kenny Clarke to rethink the role of the drummer in a jazz unit?

Max: They were masters. I was listening to Baby Dodds today. He was amazing. They are the cornerstones. When I got here, the drum set was already put together. There were foot cymbals, snare drums and new techniques to deal with it. I just stepped right onto the gravy train, so to speak. In my teaching of the history of the music, it always amazes me when I put on Fletcher Henderson’s records compared to what was done by Gil Evans, Woody Herman or Count Basie. Fletcher Henderson’s music still stands up under any kind of test. That big band just roared.

BK: You’re credited with expanding the dynamic range of the drum kit. Your manner of time-keeping on the bass drum, your ability to propel the quick tempos of bebop, and your cymbal artistry were innovative. Was it your desire to advance the role of drummer in a group that brought about these changes?

Max: It all kind of happened organically. It’s a democratic art form, and in an orchestra or small group it depends on who is with you. When Miles had the band with Red Garland, it had a different personality with John Coltrane than with Wayne Shorter, or Herbie Hancock, or Tony Williams. Even though I had bands with Clifford Brown, Kenny Dorham, and Brooker Little, I created the bands around the personalities of the musicians. You didn’t tell them who you wanted them to play like; you allowed them the freedom to be themselves and my drumming would adapt to that. If I did a concert with Cecil Taylor, I wouldn’t deal with my instrument as I dealt with it when I worked with Bud Powell. That’s the wonderful thing about this music, you’re always challenged.

I remember when Bud Powell recorded "Un Poco Loco. " It was a piece that called for an Afro-Cuban beat and I played a standard six-eight beat. Actually, you can hear the transformation now. After they put out the first one, they put out all the takes we did. After the first take, Bud looked at me and said, “You’re Max Roach, can’t you think of something else to do?” I always tried to create new rhythms at home and remembered doing something in 8/4 time. He accepted that, and it was used on the record.

BK: After Clifford Brown’s sudden death was it difficult to rebuild the group and sound in the direction you originally intended.

Max: You accept the fact about that tragedy, but it was hard. Brownie, Richie Powell, and his wife were so young. They were so full of life and such wonderful people. That loss was tremendous regardless of whether we stayed together or not. We didn’t get to hear what they’d be doing today. You grow into this business and aren’t tied to anything. That was something I’ve never gotten over. They were good, wonderful people and very close friends who loved the same things.

BK: From the late ‘50s you rarely used a piano. What were your reasons for limiting its use?

Max: The piano is a complete orchestra unto itself. Most people are under the impression that you must have the piano. The piano doesn’t need anybody, witness Erroll Garner, Art Tatum, and so on. When you hear Count Basie and Duke Ellington use the piano in their music, they let the orchestra do the work. One of the greatest pianists ever was Earl Hines. He just filled in at the right times with his orchestra when there was a little slot. It isn’t necessary to the harmonic or rhythmic structure to create. It adds to the music.

If you take a player like Sonny Rollins, when he performs you hear all the harmonies. The piano doesn’t have to be there to double; it’s all implied in the melodic line. When Bach wrote those fugues, you heard the harmonies. When you hear Charlie Parker solo, you don’t listen to the piano, just Parker. Everything is implicit in what he plays.

BK: It’s been said your work "We Insist, Freedom Now Suite," a fearless, outspoken political statement, got you blacklisted from studio work in the ‘60s. Is that a true statement?

Max: You know what happened to that, it got into South Africa. It made the news because of Nat Hentoff’s notes. One of the pieces commemorated the massacre of students in Sharpesville. It was about man’s inhumanity towards man. When it got to South Africa, the South African government banned it. It made the United Press and international news service and sold more records than I’ve ever sold. I wasn’t really banned for my direct recording. I was asked not to make speeches.

I was so caught up in the fever of the movement like we all were. The hope was happening around us. Martin Luther King was here. When I would go to the microphone at the Village Vanguard, Max Gordon would say, “Max, no speeches tonight.” I’d talk about what was going on in Birmingham. I’d say have you seen the TV tonight? I also took an active role in it as a citizen. I went to all the marches, was in insurrections around the different cities. I know they had a dossier on me like they did everybody else.

BK: Here we are 30 years later. How do you relate to the massacre that is happening to children in America?

Max: The same way. It’s really painful. Actually, the centerpiece on To the Max speaks to that in a way, "Ghost Dance."

BK: The celebrated Massey Hall concert in Toronto in 1953 has taken on mythic proportions among those who were either in attendance or somehow identify with the event. The last time you appeared in Toronto at the Bermuda Onion you spoke to the audience about that night. Would you share some thoughts on the occasion?

Max: Even though Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and myself had worked together in various musical settings, we had never all been on the same stage until Massey Hall. We were considered at that time, the young Turks. We were a new group of young musicians on the scene, so to speak. Charles Mingus got involved because Oscar Pettiford broke his arm in a softball game while working with Woody Herman. Pettiford was our first choice. We were happy Mingus came in because we had formed a record company and wanted to record.

Bud Powell, of course, was in the hospital, so we had to get him out. An incident of police brutality had left Powell deeply disturbed. It happened to him while he was working with Cootie Williams Band. The brutality affected him the rest of his life. He slowly began to deteriorate. When you listen to Bud on the Massey Hall recordings, you can hear that his playing is brilliant. That’s the thing about this music. In any case, Massey Hall was that.

So there on stage; Mingus had just come from California, he came in town with Red Norvo. We had heard about Mingus’ work with Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington. He came to New York to live, so we hired him for his virtuosity. He wasn’t as familiar with the repertoire as we were. He came on stage and did a heroic job and everything. We hadn’t had time to rehearse, so Mingus was playing everything by ear.

Tunes like "Salt Peanuts" had funny arrangements. If you didn’t know them, you’d have a hard time playing them. He clued right in. We went to intermission after the first set and Mingus dragged his bass offstage and stormed into the dressing room. We went in and asked Mingus, “What’s wrong with you?” Mingus cussed us out. “You guys from the East coast…” This, that and the other.

The fight was also going on, Walcott was fighting. The rhythm section, Bud Powell, Mingus, and I had to sit on stage while Charlie and Dizzy were running in and out telling us what was going on. It was a hilarious night and great fun. Then, after that, the Canadian Club said to us that we would share all the profits from the concert after expenses and we could take all that money back to the States. Well, the Canadian government didn’t allow that. We met downstairs after the concert, and they said you can only take so much now, and later on we’ll mail the rest to you.

Charlie Parker was hilarious; he was always in a festive mood. We’re sitting around this long table listening to these customs people explain the law to us about taxes and so on. So, Charlie Parker stands up and says in that big voice of his, “Turn out all the lights.” Now, we said to ourselves, 'we wish Bird would sit down and let the man finish talking'. So he repeated it, “Turn out all the lights.”

You know, later we wondered what he meant by it. Do you remember those pictures of Charlie Chan where somebody always turned the lights out? That’s the only thing possible we thought he meant. Dizzy and I talk about it to this day. It must have been from them old pictures when the lights went out, and then came back on, and somebody usually turned up dead. He was saying let’s get rid of this customs guy.

BK: Do you ever run out of ideas, dreams, or energy?

Max: All the time. That’s why you keep going. When you’re involved in something you really enjoy, it’s so special. There have been plenty of times I have fallen flat on my face, but you pick yourself up, brush yourself off, and go on your merry way.

Editor’s Note: Jazz at Massey Hall is a live jazz album featuring a performance by "The Quintet" given on 15 May 1953 at Massey Hall in Toronto. The quintet was composed of several leading 'modern' players of the day: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. It was the only time that the five men recorded together as a unit, and it was the last recorded meeting of Parker and Gillespie.