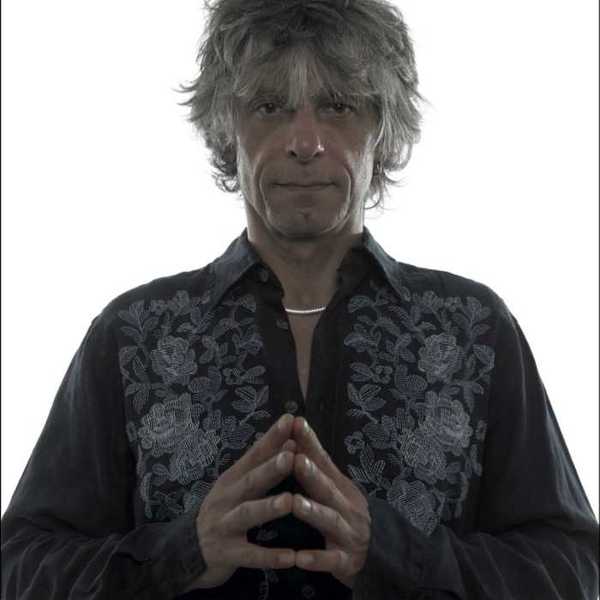

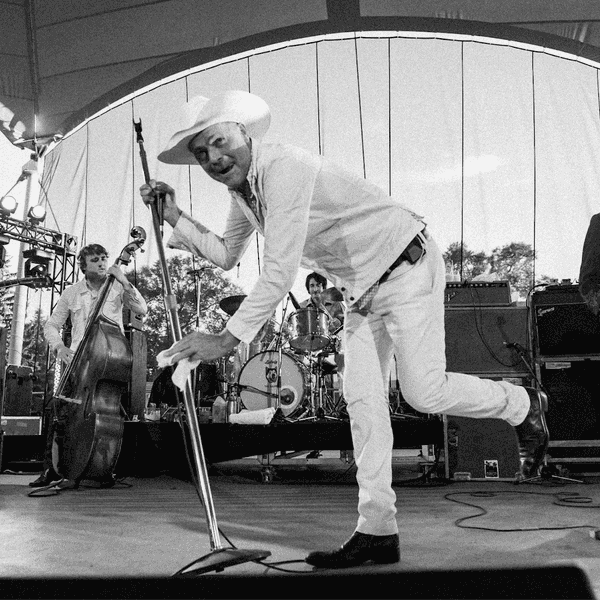

Five Questions With… Paul Kelly

The ace Aussie songsmith shifts direction with a new album that draws inspiration from the classic work of Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett. Here he discusses the project, the rapport with his collaborator Paul Grabowsky, his love of Sinatra, and working amidst a pandemic.

By Jason Schneider

Australia’s Paul Kelly has long been regarded as one of the greatest singer/songwriters his country has ever produced, with his ability to reflect the soul of the nation often compared to Bruce Springsteen’s vision of America. However, Kelly’s latest album Please Leave Your Light On, a collaboration with Australian jazz pianist and composer Paul Grabowsky, takes his sound in an entirely new direction by drawing inspiration from the classic work of Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett.

The pairing grew out of a series of concerts Grabowsky curated in which he worked in duo settings with various singers. Having known Paul Kelly since 1995, Grabowsky asked him to collaborate, and from the outset the music clicked. The 11 songs by Kelly they recorded (plus a version of Cole Porter’s Every Time We Say Goodbye) were transcribed and adapted by Grabowsky with the aim of giving Please Leave Your Light On a classic fireside feel.

As Grabowsky says, “Paul is driven by a similar impulse to my own, namely an ongoing fascination with music in its many forms. This deep curiosity has in recent years seen him explore different genres, introduce his love of poetry to his wide and receptive fan base, and record with me. The reason I love working with Paul is that he always surprises me. It’s as if we are acrobats together. We have to pay serious attention to one another to pull the songs off. I like that.”

Please Leave Your Light On is officially released July 31 via Cooking Vinyl, and Paul Kelly was able to share his thoughts on the album with us in a Canadian exclusive.

Please Leave Your Light On sounds like it came together pretty organically. What was the process like for you?

The record developed from a couple of concerts we did last year. It was part of a series that Paul Grabowsky was doing with various singers in a chamber music setting, just piano and voice. We chose songs of mine that we thought would suit that format. Intimate, tender, confessional. We booked a studio some time after the shows and went in for three days. Played the songs live, hunted them down until we had the right take. It was intense, concentrated work but very enjoyable. A good glass of red wine at the end of each day listening to the record take shape was a good way to knock off.

Were there any songs in particular that perhaps took on new significance for you in these new arrangements?

Why I like working with Paul G is that he reveals new things in the songs, which makes me sing them differently. That’s all a writer or performer ever wants—to be surprised. Sonnet 138 in particular was a big transformation from when I first wrote it. Paul gave it a heavy left-hand stomp which I had to match vocally while still keeping to the slyness of the lyric. It was a fun dance. Young Lovers turned into a late-night bar room blues, which really made the song pop for me.

It seems a lot of contemporary songwriters—I’m thinking of people like Bob Dylan and Elvis Costello—eventually acknowledge the greatness of those who created the Great American Songbook. What draws you to that music?

Frank Sinatra has long been one of my favourite singers. I know I’m not alone in this. He’s such a singer’s singer, but at the same time, he sounds like he’s talking directly to you. It’s a mystery how he does that. He’s tough and tender at the same time. Two records he made, In the Wee Small Hours and Only The Lonely, were touchstones for us on this project. They are great collaborations with Nelson Riddle who arranged them so beautifully. Of course, I’m no Frank and we chose to go minimal without orchestration. But we were aiming to occupy the same emotional terrain. Songs of loneliness, heartbreak, regret and undying love. Nothing upbeat. A real turn-your-lamp-down-low record.

What's it like for you to perform live in that setting?

It’s exciting to perform with Paul. I have to be on my toes. We set the songs up to be a three-way conversation between the voice, the piano and the lyric. There’s a fourth element as well: Silence. Working inside that silence, that space, we both have to trust each other. Like tightrope walkers.

How have you been adapting to releasing music during the pandemic, and what plans might you have when things start getting back to normal?

I had shows lined up when we first went into lockdown, which we had to cancel so, like many others, I started doing occasional posts of songs and poems on socials. After a while I collected them into a record, for streaming only, called Forty Days. ‘Forty days’ in Italian is ‘quaranta giorni,’ the origin of our word ‘quarantine.’ During the Black Death in Europe from the 14th century onwards, ships were required to be isolated for forty days before passengers and crew could go ashore.

The songs are mostly covers and you could say the record is topical in the sense that it documents things on my mind during that first lockdown, which lasted approximately forty days. I live in Melbourne, Victoria, and we’re now back into a second lockdown after an all too fleeting re-emergence. So it’s hard to say what normal will look like in the future. My plans are to take it easy for a while. Try and learn some new things on the piano. Two records out in a year are enough, anyway.

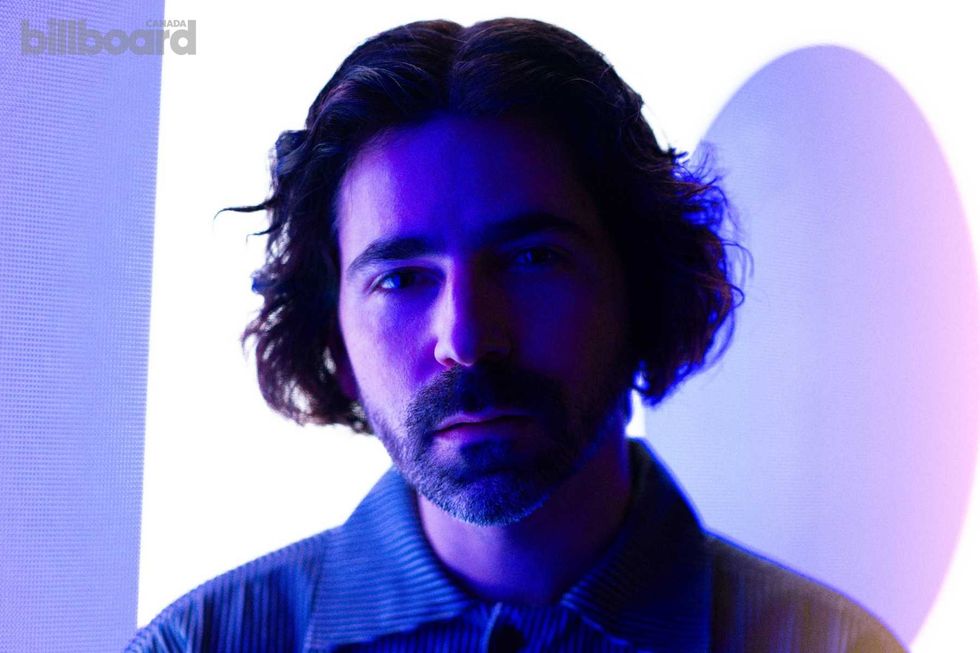

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey  Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey