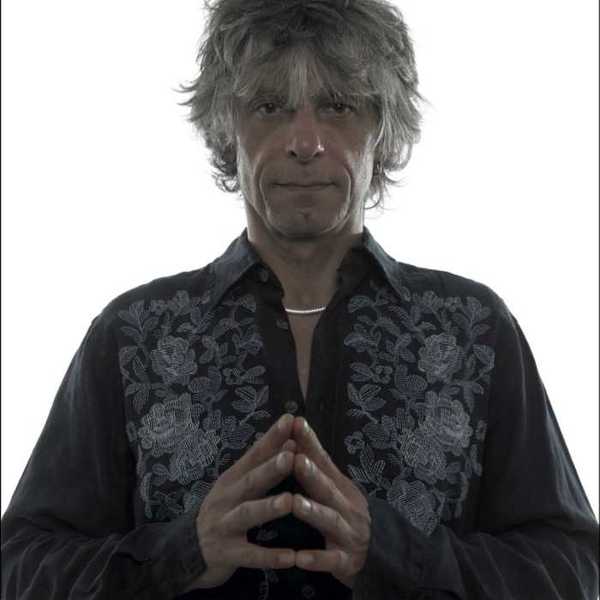

A Conversation With.. Terry Wilkins

It has been a fascinating musical journey for this veteran Toronto bassist, from Australian band Flying Circus to Lighthouse, Rough Trade and now Sinners Choir. He's a musical lifer still working hard at his craft and loving every minute of it.

By Bill King

The vibe inside is what you would expect from a British corner pub. There’s a celebratory force at play. Faces in the crowd look oh so familiar as if Saturday afternoons were meant to be a collective gathering of souls firmly planted in place for an afternoon a far distance from the usual business-like commotion of downtown Toronto and lost in the surreal confines of an ageing hotel given over to music and good times.

After packing my piano away at Newstalk 1010, on occasion I try to slip into the Rex Hotel only yards away from Bell Media radio studios and catch the last couple of numbers. This is when the band is cruising to a finale and the crowd, jammed from door to door, is in a receptive celebratory mood. The room is alive and electric!

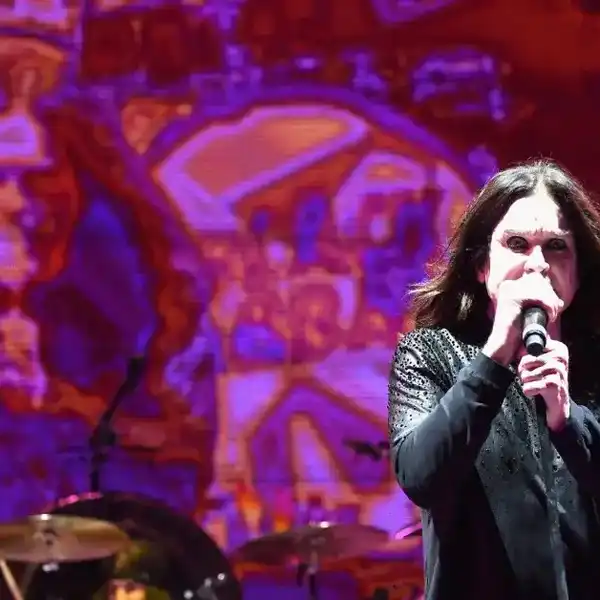

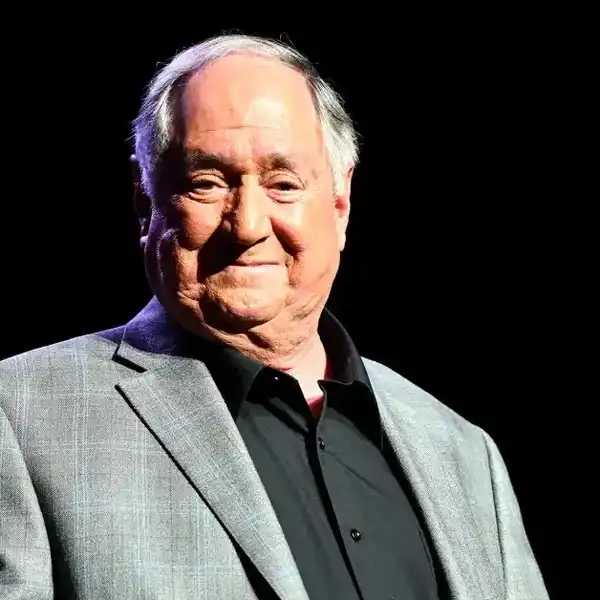

The band on stage and charged with keeping the energy high and the crowd engaged is led by the man with more activities scheduled in a week than most musician’s over a two-month period, bassist/vocalist Terry Wilkins.

Wilkins turned 70 a few months in the rear, and I made a point of dropping by to congratulate. Seventy is a milestone in any profession and deserves recognition.

I catch the rousing 2:45 p.m. closer and close in on Wilkins who by 3:01 is applying the outer skin to his acoustic bass and clearing the stage. Wilkins looks panicked yet pauses long enough to embrace a moment between two ageing music loyalists before jetting out a side door. Wilkins was on to the next gig.

Through the years, this is how I’ve got to see Terry Wilkins. Not long ago I trapped him early morning for an interview and here’s a portion of that conversation.

We first met in 1971 when you arrived from Australia. Why did you centre on Canada?

Actually, there was a sequence to it in 1970. McKenna Mendelson Mainline went to Australia. We played some shows with them. Personally, I loved McKenna Mendelson Mainline. They were an amazing live act and at one point we were playing in Melbourne and the bass player was a guy named Zeke Shepherd. He was actually a world-class harmonica player, and he was the bass player in Mainline for a little while. He was a very simple player, but fantastic. I thought the guy was amazing. We got to chatting backstage and he started talking about Toronto. At that point I knew nothing about Toronto other than the fact that all our schoolbooks were made by a publisher who published out of London, Toronto and Sydney. When I was at school I’d see the word Toronto which always reminded me of Tonto. He gave me a business card which I gave to our agent.

In 1971, that band, Flying Circus, moved to San Francisco. We were negotiating a deal with Capitol U.S., but couldn't work. We were just chilling and going to the Fillmore West, which was pretty amazing. Interestingly, Toronto band, James and the Good Brothers were living in San Francisco and managed by Bill Graham at the same time.

While in San Francisco our agent from Australia went to New York to do some business. He had a green card and decided to check out Toronto. He met with the Music Factory which was an agency at 80 Scarlett Rd. He saw that people worked a lot. And what people did work a lot at was high school dances. The drinking age was 21. Even when kids left school, they still went back for the school dances because it was the only action there was.

He called us up and said, ‘as long as you're waiting out your deal, why don’t you wait in Toronto,’ and we said great, we'd love to play. We were getting a little Jonesy at that point. The band took a bus to Vancouver, then on by train. We saw a good chunk of Canada right off and spent a few months in Toronto, and we decided that we'd rather be here. We got signed to a management deal with HP & Bell, Lighthouse's management. That was March of 1971. I’ve just had my forty-sixth anniversary of arriving in this country.

We were in the same package deal. It was me, Bob McBride and Flying Circus, a three-way deal with Capitol Records. Every time I went to visit Paul Hoffert, Scientologists would stop me on the street in front of HP & Bell - harass and ask to evaluate my personality.

What was the name of that restaurant across the street? Plato's Symposium, right? Cool. And that was full of them too. I used to watch them berate each other. That was very interesting.

You got a foothold. Made that record. Got out to play and stayed in place in Toronto.

It did happen organically. I'm not much of a planner. I don't really like plans because they spoil life. We were winging it. It didn't take me long to realize I liked being here. I went from Flying Circus to Lighthouse and then I began feeling like I was deeply involved in the Canadian music scene at that point.

This was with Skip Prokop and Lighthouse, and they certainly did tour a lot.

One thing about touring is we did the first ever beer sponsored tour, with Labatt‘s which was interesting because they sent along a young rep who travelled on the bus with us. Frankly, I think we destroyed his life.

You took care of him, ‘real good’?

I think he never got over it. It was just too wild for him. I think we did sixty-eight concerts in seventy-five days, with some insane bus rides from Victoria to St. John's.

Were you comfortable driving a great distance between gigs?

I haven’t done much since that.

Leave that to the 20-year olds?

I don't have anything against that and don't try to do it. When I became a parent, which is thirty years ago, instead of being in one band that did a lot of things, I ended up being in a lot of groups doing a few things. Then I could be home all of the time.

I felt the same way when my son was born. I remember being in a club; it must have been in Belleville or somewhere. I'm in a hotel room with a band member and booked for a week. First night away I look around my hotel room and see another musician rolling up a pillow, and thought, ‘damn, that's not my family’. I’ve got to get back home. I realize it’s imperative for young bands, but rarely profitable.

It’s expensive to do. I don’t know of a situation where I would want to be that hardcore and on the road again. But that said, who knows. If anything, it would be with the Sinner’s Choir. I could get into that.

That’s your current project.

Yeah, we made an EP last year. We're currently mixing twelve new tunes; originals etc. The past EP has helped pay for new recording. We sell it off stage. I like that low overhead.

It sounds like the first days of the record business, doesn't it?

I think that these days aren’t that dissimilar from the early days. In the early days, there was no industry. Right? Especially, for rock ‘n’ roll. I think there was like the ‘bright lights’, the A&R guys who were going out on the street and finding cool people. That was the record business. And then it became what it became, which is a bloated cocaine-filled behemoth.

The music industry in some ways has fallen apart, and it makes young musicians and just in general musicians not want to tailor what they do to the music industry but do what they think.

Subsequently, I think the demise of the music industry has made for better music.

There’s something reassuring about sticking with what you know.

I refer to it as the no alternative music. Just play what you play. How it falls is how it falls.

You’ve been playing the Rex Jazz Bar with Sinners Choir the past two years from noon to three every Saturday afternoon.

That's right. We've been there for a couple of years now. Indeed, the audience has grown.

Playing original music at noon was a little tricky at the beginning because people were a little befuddled. A couple of things happened. We realized that playing rock ‘n’ roll at noon is a little jarring. So, for the first of our three sets, we got ourselves a bluegrass mic and set that up in the middle of the stage. We do the first set with string bass, acoustic guitar, and washboard and three voices around one mic. Which is a nice gentle way to start the day. But it has also opened this up to a whole other way of presenting yourself. Especially, when you're playing what's basically a bluegrass instrumentation and bluegrass approach to playing, and the music isn't bluegrass. It's whatever we play and often we'll be playing in that format and will be counting off a tune and I realize I've never played this actual tune in this format before. I have no idea how I'm going to approach it, but I also have to sing. You know what I mean?

You‘ve said the more time you get in the recording studio, the easier it gets. You used the term ‘red light’ fever. What does that mean?

Well, sweaty palms. Let me just preface this by saying. In the [Toronto blues club] Albert’s Hall days, drummer Bucky Berger and I worked with Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson and became very good friends because he came up here quite a lot of times He took us under his wing and gave us some good advice and all kinds of things. And one of the things he said to us was, ‘you realize it's a 30 -year partnership,’ and I was in year twelve at the time. I thought that seems unreasonable. That's too long, and it only made sense when I got to thirty years.

I think that the ‘red-light fever business’, which is where a musician’s brain starts to seize up when the red light goes on in that recording studio, and he gets overly cautious. The music’s not as flowing. Now I don't care. I just go and play. I don't even think about it because I don't care about mistakes particularly. What's a mistake anyway? Who's to say what a mistake is?

Regarding how we initially viewed the recording studio, going back to let’s say a Sun Records - players showed up and played. They played what they knew and with big emotion. You didn’t overthink. Once music went corporate, it became a factory product. I think that's what kind of stressed everybody out – especially young musicians new to the process. It began limiting the creative process.

I think so. Even though in theory, as we both lived through the 24-track explosion and the thing about that was, …… I did Eddie Schwartz’s first record in the Catskills many years ago. The studio they used was the Record Plant - the remote set-up. They rented a house in the Catskills, a twenty-room mansion and, during the process of making that record, there was a huge kerfuffle with Bruce Springsteen who was recording at the Record Plant. It was with senior management of 3M, because Bruce had overdubbed so many times he wore out the two-inch tape before they got to mix. I think they lost tracks. They wore out the files or whatever the technical thing is.

Didn’t the same thing happen to Fleetwood Mac with Tusk? They spent a million making the record.

That was the first million-dollar recording.

They ran the tapes nearly every-day and overdubbed until the iron oxide had worn down. I’m with you – it’s still about the moment.

Perfection is overrated. And I think that multi-track recording, when it came in, did play to people's desire and ability to be perfect, which of course turned out to be a waste of time.

Are you still a fan of recorded music in its rawest form?

Think about it. Before there was the ability to overdub, the only people who could go into the studio were people who could play freely live. After multitrack, legions of people who couldn't do it were taken into the studio and overdubbed until they got it right.

When Sinners Choir went into the Rex, I sent Tom the boss a YouTube video of us playing live at the Gladstone. As crude and straightforward as you can get. Later, I was talking to him, and he said, ‘Well you know I could see what you guys do, and that was exactly what I was going to get.’ He then said, ‘sometimes people bring me in their recordings, and I put it on, and I think, I wonder if that's take fifty-six?’ That's the advantage and the disadvantage of modern recording. People can fix, so they will.

I like to play Sarah Vaughan for aspiring singers. Vaughan in the studio at nineteen or twenty. She just stands in in front of the band with one mic and sings ‘absolute’ perfection.

It's interesting you should pick Sarah Vaughan because in my run-throughs with young musicians and most especially with young female musicians, I always send them to Sarah Vaughan. Sarah was the perfect melody singer. She knew why those guys or gals, whoever wrote the music, why they chose that sequence of notes. They're lovely and then you realize so many people learn jazz songs that are interpretations of originals without actually learning the notes.

It’s the affectations that murder a song.

I blame Stevie Wonder. I would often say to the youngish about the standard format of jazz tunes, ‘A-A-B-A’ and I remind them the first ‘A-A-B-A’ is by the book. And what you do after the solo is; feel free. The other thing is, I encourage people to make the first line of improvisation about phrasing, rather than about note changing. You can take a perfect rendition of a Duke Ellington melody, and you can phrase it dozens of different ways that define an original approach to the song without ever altering one single note that Duke wrote. Whereas, you know yourself, how many times do you hear jazz singers who have changed a melody by bar three of the song? Not that I'm against improvising, don't get me wrong.

You’ve weathered and aged well with your music.

When we were in our early 30s, we worked at Albert’s Hall a lot and played with ‘Cleanhead’ and Sunnyland Slim and lots of those old guys. The first one we worked with was Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson. Bucky and I spent 6 a.m. until 9 p.m. on a sound stage doing one of the first ever videos, ‘All Touch and No Contact,’ for Rough Trade. At 9 p.m. we left the set and went to Albert’s Hall to play our first of six nights with ‘Cleanhead’. I don't know what we thought we were going to be doing but, I guess it was something like there was this old man and he needed a rhythm section. We were going to go in there and prop him up because he was a fossil. He was 68 at the time.

‘Cleanhead’ and Sunnyland and all of those old guys we played with were better than anyone we’d ever played with. No fat on the bone. Everything meant something. There was no waste. Amazing, amazing. It cured me of getting ‘old itis’.

A lot of people, especially from our era who grew up playing rock 'n' roll, the first thing was, you can't play rock ‘n’ roll after you're 30 if you recall that. Right? And then it was 40 and 50 and whatever. Those guys, as I say were better than anyone that I’d ever played with, and it changed my perspective on ageing as a musician to a much more tempered one because I was looking forward to a lot of it. That's the truth. After you've played a certain number of notes, things get easier in your brain, and you stop panicking. That may not be for everyone, but it certainly is for me because I'm essentially an autodidactic musician. I never had any lessons. Everything I’ve learned is by the seat of my pants, and I’m frankly still doing it that way. The ageing thing is not as bad as I expected.

Before the Beatles, it’s all about Elvis, and I look at the both of us and how fortunate we were to be at the front end of rock ‘n’ roll. The fifty years that follows is an amazing era of music. Being in the recording studio when it was monaural - the first time we hear stereo played through speakers, then 4 tracks, 8 tracks, 16 tracks, 24 tracks, 32 and to where we are now. You must think to yourself, WTF just happened?

It seems like 100 years. It did go way too fast. But the essence hasn't changed. The bottom line is, if you can do it, you can do it. If you can't do it, you can fix it, and it will never be the same.

You've taken good care of yourself. Sometimes you do three gigs a day. That's insane. You say you’ve conditioned yourself to play until four in the morning and then up by noon.

I’m a night owl.

You don’t run low on energy?

I never run out of energy. I think that with ageing, as long as your body doesn't fall apart, touch wood, and the mind is holding up pretty good, your ability to meter your energy becomes way more refined. Even though you don't have as much explosive energy as you had when you were young, messy energy as I call it, it's reliable and consistent.

Being a bass player, both my instruments are raised for high action and hard to play. I like that. I like the resistance. It means you’ve got to be in top shape all the time or you run out of energy. I've learned to stay below the red line. In other words, don't play too hard or you'll run out of steam. Nudging that line below playing too hard, which means you’re kicking it pretty hard, but you're not wearing yourself out. So that's how I get through nine sets in a day.

Where did you grow up in Australia, and what was being a kid like?

I grew up in Sydney, Australia, Irish Catholic. I started playing music pretty late compared to most everyone I knew. I think I was seventeen when I first started playing music and everyone I knew had started when they were eleven or thirteen or something like that. So, I was kind of behind the ball, but I made up ground fast and think I turned pro in about a year and a half. As a matter of fact, the third of June of this year is my fiftieth anniversary since I've become a professional musician.

Let’s go back before that. What was the young kid running around the neighbourhood up to?

I lived in the city. Sydney is a big city. Have you ever been there? It's huge. It had a million people in 1948. I was a city boy educated by Irish nuns who grew up on farms. Whose approach to education was similar to their brother’s approach to breaking horses.

Did you get hand-slapped with a ruler?

I think I probably got hit every day from four years till sixteen years of age. I went through a conventional upbringing, and of course, in those days there was the beach. We were surfers. Nobody even thought about not being a surfer. I did own a surfboard.

Were you a smart kid in school?

I did well in school. But I always got into trouble a lot. I guess I was a smart mouth and they never liked that. There was a lot of music in my family, but it was all amateur. My mother was conservatory-trained but could only play with sheet music. My father knew nothing about music but would attempt everything, and he was a good singer.

There was an artist in the 50s’ who was huge in Australia named Winifred Atwell. Do you know who that is? That's very interesting you've never heard of Winifred. She was very big in Australia, and she was very big in England and came from Tunapuna in Trinidad and played boogie-woogie piano. And serious. I went and dug up some of her recordings lately. She was ‘intense’ fantastic. The only thing that my mother could play without sheet music was her rendition of a boogie-woogie by Winifred Atwell, and I loved that. I was five and I used to say, ‘play boogie-woogie’, and I would reach up and grab my mother’s right hand, so she couldn't use it. All I wanted was to hear the left hand and I was five. I think I was born into being a spy.

Did you ever get bit by anything lethal?

Nothing serious, but you know what, that's only luck. There's a spider called the ‘funnel web spider’ - and it's poisonous. The epicentre in Australia for the ‘funnel web spider’ is downtown Sydney. There are a couple of others; red backs that will bite through a leather shoe. There are also snakes.

I often wonder why all these things thrive in Australia. I mean there were other countries they could've picked.

I know. And as well as that, there's the weather. Right now, in Australia, there’s hurricanes and flooding. Australia is either flooding or burning. That's life. That's how it goes. It's no place for white people. It’s way too harsh.