A Conversation With .. Patrick Harbron

The Toronto music scribe turned photographer now does A-list set work in the US while also reprising his work from the glory days of the rock scene. This extensive interview chronicles his journey.

By Bill King

Look across the '60s/'70s/'80s and those near and behind the rock scene who captured musicians in various situations, you see photographers Jim Marshall, Linda McCartney, Barrie Wentzell, Annie Leibovitz, Bob Gruen, Christopher Angeloglou, among others, come in focus. Many linked to magazines and record labels. Some boarded a bus, a plane, or had an in with venues and managers and record labels and secured full access and the confidence of bands to shoot at will.

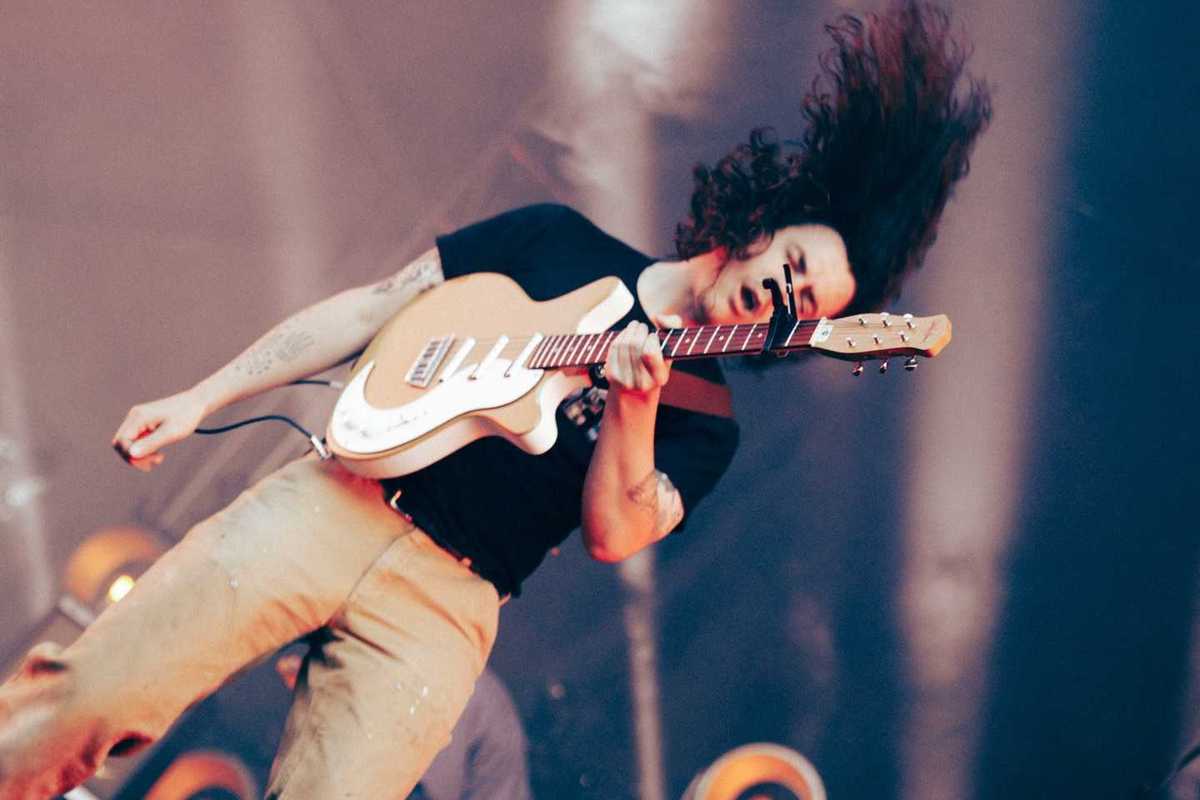

Following in their footsteps, Toronto photographer Patrick Harbron was one of those shooters, creating an impressive catalog of epochal musicians. Some are portraits, many photographed “in the pit” - that predetermined area where shooters stand shoulder-to-shoulder and jockey for position. The shutter snaps, forever sealing the action.

The industry underwent a massive shift as technology made it possible for anyone with a smartphone to snap a likeness of their favorite artist. Technology has its limitations, and the demand for vintage photographs of artists from the past remains strong. Before the tech wave, Harbron retooled and created another career of shooting portraits for magazines and advertising after relocating to New York City. In 2006, taking a page from his varied career, he returned to “set work” - shooting for television and movies.

Bill King: I’m thinking you would've enjoyed being on the set of The Irishman since you’ve already photographed many compelling moments in film and TV - including the award-winning television series The Veep and House of Cards. As a photographer, you’ve got to appreciate “set lighting.”

Patrick Harbron: I do. Many don’t know what an onset photographer does. I have to wait until everything's ready. Then I cover it, and all the crew who are doing the hard physical work are looking at me like I’m on a busman's holiday, which of course, is true (laughing). But it's good work.

B.K.: I'm looking at the Julia Louis-Dreyfus images from the set, and you capture her expressions precisely as seen on The Veep.

P.H.: Thanks. The actors and actresses I've worked with are excellent. Julia is among the best and amazing to work with. She created an environment where everybody wanted to be more productive and positive. On that show, sometimes we had to cut the taping because we were laughing so hard.

B.K.: House of Cards. That must have been a strange set?

P.H.: It was a creative set. I only did season one and that was incredible because of the high production level and what it was saying. After a while, if you didn't want to watch later work like season five, you just picked up a newspaper to see it unfolding for real. It was something else.

B.K.: How long is a workday?

P.H.: When I go out of town, I'm on set a lot, often daily. With film and movies, it's usually every day. And with TV, they pick scenes or episodes they want you to cover. Maybe it's a guest star or a particular turn in the script they want “visualized.” And now with social media, it's not just the picture in The New York Times, it's stuff everywhere. It lives all through the Internet. There's demand for a lot of photographs.

B.K.: And it's immediate, and I imagine you have to clear everything before it leaves the room.

P.H.: Certain artists have approval - their photos aren’t released until they've seen them. Many of the people I work with are like that, and it's all done through the network. I'm hired by networks to do the photography.

B.K.: I was thinking that last night, while watching The Irishman, the significant physical alterations courtesy digital technology and regeneration of De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Al Pacino. It looks a bit strange.

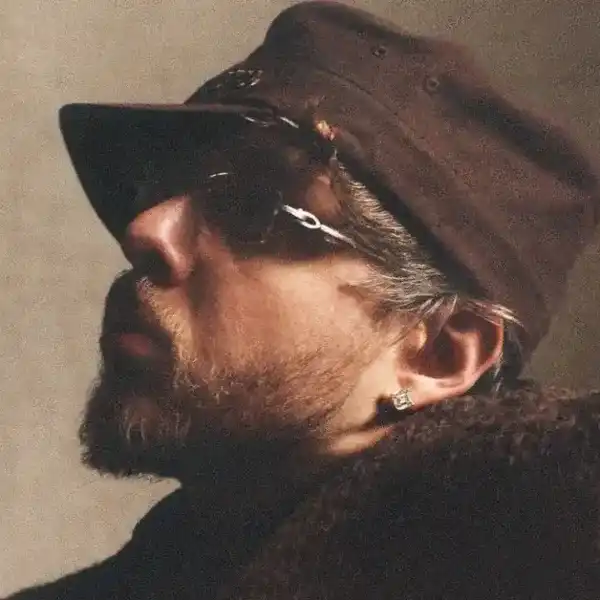

P.H.: It’s on Netflix, I want to see it too. I haven't had a chance. A lot of my friends worked on it. I photographed De Niro for another movie. I was doing a portrait of him, and I had a list of things I had to do. I'd never photographed De Niro before. There was a list of photos to capture, a distinct look for the usage.

I said to him, “I have this list to complete.” He said, “Fine, then just direct me, and we'll go." And then, “What's the matter?” I said, “Nothing. I’ve been doing this for thirty-five years and never imagined the day when I'd be directing Robert De Niro.” He said, “Well, today's the day; let's go.” He was very gracious.

B.K.: Recently, Stephen Colbert goaded – calling him “Mr. Tough Guy.” I’m curious where you got your start Patrick.

P.H.: I’m from here, Toronto. I grew up in the west end - Islington. I was telling someone in England this, and they said, “Islington?” I said, “Yeah, I lived on Elstree.” They went, “That's the studio.” Everything in Toronto; Anglesey, Kingsway, Wimbledon, Swansea, Runnymede, everything in English. All the street names from way back when.

B.K.: Your childhood; you and the camera?

P.H.: My father was a journalist, and he often shot photographs to accompany his articles. And from that, I guess I picked it up. I was a writer first in the early ‘70s. It took a while for me to become a photographer. It wasn't something I gave much thought. I was always involved in music. I was a drummer in a band, and then I became a writer, and, all through that, I was associating myself with music, so when I found photography, I was thinking visually, but until then, I wasn't.

B.K.: You wrote for a few local music papers?

P.H.: I wrote for Record World as a stringer, with an editor here. I worked for Beetle Magazine, RPM, Sound and Pop, I think. I never did work for Guerilla newspaper, although they published within a block of here - I think they might have originated out of Rochdale College. It had an edge to it. Downtown was the music center of Toronto. Well, people in Scarborough might argue with that.

I saw all these shows that I never photographed because it didn’t occur to me. I was a writer. I was thinking of describing it with the printed word. But the idea of visually capturing something and seeing the light and shape and color - I was aware of it. We all were - that's what turned us on to a show, plus the music. I became a photographer in the mid-‘70s and had to make a choice. The choice was photography.

B.K.: What was the first concert you photographed?

P.H.: I was interviewing Black Sabbath for Music Canada Quarterly in 1971. The band was here on their fourth album and the first time in Toronto. Humble Pie, which was always a favorite band of mine, was there too. I picked up my friend's camera. He was photographing the article, and I was doing the interview. I photographed Humble Pie’s drummer, Jerry Shirley. My first rock and roll photograph.

The first camera I bought was in 1975, and I took it to a Who concert. I was told how to do everything with the camera by the salesman, but he never explained shutter speed. So I shot it all at a 1/8 of a second. Everything was very blurry. I had no clue.

The first gig I was hired to shoot was for A&M Records. I was self-taught and at a Supertramp concert I met their photographer. We became friends. He had a studio, working as a fashion photographer and doing some music stuff on the side. I apprenticed in that studio, staying there for three years. That was what got me everything that came afterward, frankly.

B.K.: Were you shooting medium format?

P.H.: Both. I shot on 2 1/4 for about 20 years. Now that I'm working on film sets, I use 35 mm, and it's all digital. There's no film anymore. The three words I thought I would never say; “better than film.” I shot all the landscape and portraiture for exhibitions on 2 1/4 Hasselblad. That was from the mid-‘80s. I bought that gear in 1983; the real stuff. The images to this day are beautiful.

B.K.: Recently, several images were shown at Analogue Gallery in Toronto. Are a good many of them medium-format?

P.H.: Yes. It's a mix. Portraits of people like Ray Charles – that is medium format stuff. Robbie Robertson; both shot on 2 1/4 Hasselblad. Most of my music portraits are on 2 1/4. For a while, I didn't even shoot 35 mm unless I was at a concert or on holiday.

B.K.: Freddie Mercury from Queen?

P.H.: That was 35 mm, and that was for Queen’s video, Body Language, from the Hot Space album. WEA Music called me after Queen’s management asked them, “Do you know a photographer? Bring him along.” I went to this video session, and they let me shoot whatever I wanted. I was pulling them off the set throughout the day.

The portraiture that I did was all 35mm, even the lit portrait that I shot of the group. I was at Magdor Film Studios, where A Christmas Story was shot - a movie I had to turn down because I wasn't in the union. The time with Queen made quite a day.

B.K.: Your live presentation, An Evening of Rock and Roll?

P.H.: It’s a spirited stroll through almost 20 years of rock and roll - through my eyes and my camera. I tell stories that can be repeated of all of the bands — everybody from Eric Clapton, Madonna, Blondie, Led Zeppelin, Bob Marley, Grateful Dead, Van Halen, David Bowie. There's lots of Canadian artists too: Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, k.d. lang. It really crosses a lot of ground. It's a fun talk and goes on for about an hour. Q & A follows. Then it’s off to the pub.

B.K.: What was the first photo you showed your dad?

P.H.: Oh, that's interesting. He was a better writer than a photographer. He would probably agree with that. I apparently showed him something. I’m guessing when our band rehearsed in the basement he was already up to speed with what was going on with his son’s and rock and roll. I think probably a photo of The Who.

I was going to Eddie Black’s because I had no way to print photos. I’d take the slides in to have quick photos made. Little 5x7’ prints. They would ask – “What band do you have today?” I’d disappoint the guy behind the counter because I never had The Carpenters. I occasionally had great shots, and I would probably show those to my folks and my friends as they popped out from Eddie Black's lab.

B.K.: What are some of your favorite concerts or sessions?

P.H: There are many. That’s tough. I remember several shows I didn’t photograph that informed me visually - Genesis, Bowie and Pink Floyd from the early-70’s. My favorite shows to photograph were of groups that understood how a visual experience would make the concert a memorable event. Kiss and Van Halen shows in 1979, Springsteen, 1978, Pink Floyd, 1987, Tangerine Dream, 1986, Nektar, 1976, The Tubes, 1978, The Jacksons 1984 Victory tour and any RUSH show, immediately come to mind. I loved shooting Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen too. Dates at the El Mocambo with Blondie, Boomtown Rats, and George Thorogood were amazing. My portraits of and time spent with Ray Charles, Les Paul, k.d. Lang, Carlos Santana, Deborah Harry, Lyle Lovett, and Queen are among my favorites.

B.K.: Any stories or observations?

P.H: How much time do you have? (laughing). There were several situations that reminded me of how insular a rock band could be. One concert displayed many of these elements in a single go. The Scorpions, the German hard rock band, performed in Toronto in mid-August, 1984. The concert was at the CNE Grandstand. As soon as the show started, following rumbling sound effects and plumes of effect smoke, a large pod slowly rose from beneath the stage. I began to laugh as soon as I spotted the stage prop. It was very familiar.

The tour photographer glanced over at me. He was puzzled. “Why are you laughing,” he asked? I said, “Look at the pod with the smoke gushing out. This is Spinal Tap!” “No, he insisted,” not making the connection, “This is Scorpions!” Maybe, but this show’s opening looked like an out-take from the famous mockumentary that made solid fun of the life of a hard rock band. Apparently, the members of Scorpions were unaware of the film.

As the story goes, when a Mercury Records promotions rep in Chicago took them to see it, they walked out of the theater in disgust. The promo guy almost lost his job. True? Who knows, but the episode in Toronto happened, and I will never forget it.

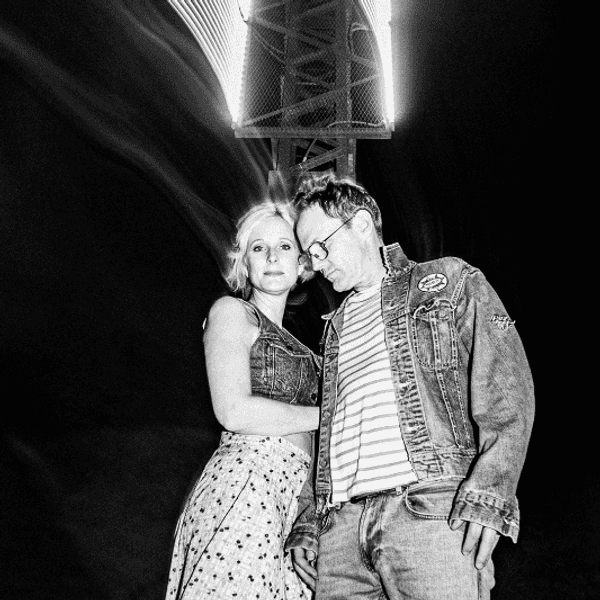

My portrait of Lyle Lovett was a perfect example of collaboration and creativity. When I got the assignment from Southpoint Magazine, the concept for the portrait came to my mind even as I was on the phone with the art director. The idea was to shoot the singer in profile matched by the profile of his guitar. The portrait was scheduled to take place on tour at Atlanta’s Fox Theater. I would have 30 minutes.

Lyle was opening for Bonnie Raitt, and the session would take place after his set was done. When he came into the room and saw the setup, he frowned. “Everything OK,” I asked? “Oh yeah,” Lyle said, “This is great, but I can't be photographed from the left-hand side. It’s just the way I am.” I agreed, “No problem. My assistant and l will have to dismantle the set and build it again. Is that OK?” It was, and Lyle sat until we were both happy with what we had. He apologized because he knew I wouldn’t be able to see Bonnie’s show. Amazing guy. It was one of my best sessions. Later in the year, he invited me to his concert in New York, where I gave him a large print of the photograph.

B.K.: Shooting from the pit can be fun.

P.H.: It depended on the show. I was recently asked what it was like to shoot the Stones during their Steel Wheels visit to Toronto. There was a lot of excitement at the beginning of the 1989 tour. Photographers pushing and elbowing, and we were all made to line up. It was like the last helicopter out of Saigon. “Hey, it's a rock show – can you give me a little space? Relax. I need some space. You'll get out of here soon enough.”

Pit shooting at a concert is controlled chaos. Photographers are kept waiting in the front for the longest time, then limited to the number of songs we could shoot at the concert.

When I shot that work, I was trying to capture the essence of the performance. I wanted you to hear the music in the photograph. I wanted that photograph to tell you what that show was about. I didn't have the luxury of an entire performance. It was usually three songs. A lot of artists would make you work like that. If you had a deep stage and your guy was back behind the drum kit for the first three songs, you hated him.

This was a very different situation than a portrait session, where you control the environment and hopefully, the outcome of your time with the artist.

The successful portrait, the result of an idea and collaboration, is very satisfying. It is your creativity and point of view of the subject on display. It is no less pressure, just a different kind.

B.K.: Then there's B.B. King, who would give you everything in the first 30 seconds.

P.H.: He's shown in my photograph with his guitar, Lucille. Number 17. Yeah. The real deal. He gave the guitar a hug for me, and I made the image of that. He was a gentleman from a different generation.

B.K.: But he knows what photographers are all about and what they're doing.

P.H.: I photographed Ray Charles, and Ray understood that - he understood the visual, even though he was print disabled. I mean, it was terrific how prescient he was. Living in the present, he understood what it meant to put himself out there. When I did the session with him, he gave me a hundred percent.

Robert Fripp came to the Bathurst Theatre in 1979, and he wouldn't let me photograph him. He said, No, I don't think it's necessary. I said, “You know, you're just sitting on that bench - that's a solitary figure you're cutting visually? Oh, well, you don't want to…”

He says, “What do you mean?” “Well, I really, I think you look - just let me back up here…” “OK, just a couple," he said, "you know, just a bit.”

B.K.: So you have a technique. You've got to be smooth.

P.H.: You have to be trusted. The photos you take in the pit down front or in a controlled situation - it's what you do with them afterward that counts. When you make a portrait, that's you laying your vision out there. When you shoot a performance, you're recording what the artist is giving you, and you can choose your angle and later select the photograph. But the portrait is a construction, and the performance is reportage. They're entirely different kinds of photographs. How you present the artist depends on how you make the photograph and how you deal with it later.

B.K.: What about those smartphone snaps?

P.H.: I was at a King Crimson concert last year. Robert Fripp and his band have big signs at the front of the stage - “No Cell Phones.” Fripp would point like a stair monitor from his podium if he saw anybody with a phone, and if they didn't put it down, he’d have them removed from the concert. It was like, when you're buttoned-down, like Fripp, it works. There's nothing worse than the guy in front of you who’s not just taking everyone's picture; he's videoing it. “Tell me, when are you gonna watch this? Later? You can watch it for real right now. You know what? There's a DVD, dude. Why don't you go and get that? Stop filming in front of me!”

B.K.: What gear are you carry around?

P.H.: What I use now is a kit of three lenses. All Sony. I'm using the Sony A9. And I hope they're listening because when the A10 comes out, remember this interview Sony (laughing). The cameras are stunning. I switched to 35mm when I came back to doing a lot of television in the mid-2000s and stopped using the 2 ¼ because it was for a different kind of work. I was using Canon until 2016 because I always had, but the Sony cameras are a mirrorless system. They're lighter and incredibly efficient. Sony was the first manufacturer to get this kind of professional camera equipment to market.

I have a case that I carry on airplanes and hump around the subways of New York, which is just way more convenient. My primary gear is three lenses, two bodies, and a bunch of accessories - I'm self-contained. There was a time when I would be describing my drum kit; now it's my camera kit.

B.K.: It's great to cut down.

P.H.: Until I have to do a big photoshoot and I turn up with 14 cases of stuff to plug in and light up. That's when I get two assistants, and I say, “It's your back, not mine.”

“Can you help me with this, Pat?” “Nope!”

B.K.: What's coming up?

P.H.: I'm working on a couple of projects based on this work, and I'm continuing in TV and film. I also license my rock and roll work and sell limited edition prints to collectors through my website rockandrollicons.com and galleries like Analogue Gallery in Canada and Morrison Hotel Gallery in the U.S.