A Conversation With ... The Orbit Room's Tim Notter

It's midway through the afternoon and you are loading in gear, pause, then glance across your new surroundings.

By Bill King

It's midway through the afternoon and you are loading in gear, pause, then glance across your new surroundings. The room is brightly lit and, just out of view, a cleanup crew is sweeping away the rubbish from partygoers the night before.

The sign out front grins history, a room where the legends of the past cut the competition down to size. Yet, there is something amiss in all this nostalgia beyond the awareness you are about to open tonight. It's the mustiness of the location; the grit and blemishes daylight exposes before the sun recuses itself and the lights are lowered. You tell yourself, 'man, this is just another shabby-looking joint,' not one you've read about in books, newsprint and magazines where countless upshots have performed on an undersized stage.

Oh, how the tales and rumours of glorified edifices latch to memory and test the veracity of the moment.

Night rolls in, and the crowds gather. You're now ten feet from the stage, turn, then inspect the amber-lit room and recognize the celebrated faces staring back from dimly lit posters. To one side, wall-mounted neon signs advertise beer on tap. Down front, tables crammed with socially willing patrons and back of the room a bartender attending regulars and waitresses pouring and delivering at a furious pace. You've seen the photographs, heard the recordings, and read the reviews. Suddenly, you realize the room has a genuine pulse and a purpose and has righteously earned its place in music lore. As nighttime comes, the room transforms into a thing of austere beauty, and it's everything you've imagined, and now you are about to write your first chapter.

Before I began interviewing The Orbit Room's Tim Notter, I thought back to the many small venues I've visited over the past sixty music years: The Village Vanguard, The Village Gate, The Night Owl in NYC, The Whisky a Go Go, the Blue Note, Café Wha, Steve Paul's Scene, Café Au Go Go, The Bottom Line in NYC, Ciro's on Sunset Strip, Shelly's Manne Hole, and the history behind these well-regarded establishments.

In nearly every situation, it's the bands that write the story and are the draw, and in daytime, the rooms look mostly uniform as the mop hits the floor. In Notter's and Rush's Alex Lifeson's space, the Orbit Room, music certainly was the calling card and the key to the room's 25-year run, and yes, the Orbit earned a place amongst those mentioned above. We talked.

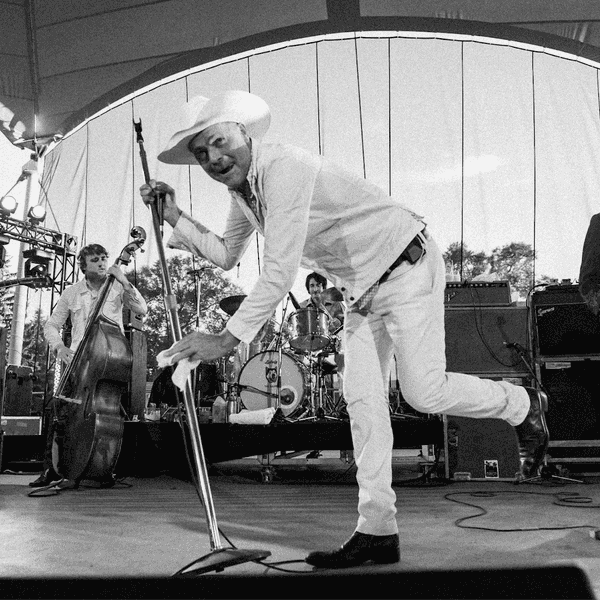

Bill King/Stacey Kay/John Finley/Collin Barrett/Mark Kelso at Orbit Room, 2011

Bill King: There is still a sign out front on College Street advertising the Orbit Room.

Tim Notter: I had to let it go and I’m incredibly lucky. I got to weather the first three and a half months of the pandemic without having to pay the rent because I was about to sign a new lease, the lease was up. I already had the papers but hadn’t signed them. A year ago, in March I got together with my landlord and for most of the time I had been there he had been incredibly unreasonable. If I was to write a book about opening a restaurant the first thing I would say is, meet and talk to your landlord because that connection is crucial to how well you are going to do. Mine treated me horribly for twenty-five years. I’d already signed a lease, spent my money and owned the place and couldn’t get out of it. If I had known how horrible it was going to be dealing with him for twenty-five years, I would have never signed that lease.

B.K: How long was the first lease agreement?

T.N: I was in the third year when I signed up for seven more years – ten years. The rent was only $1,200. Alex Lifeson and I looked at it and thought, how bad can this be? The guy before me had spent a lot of money renovating the building; we thought it was a tremendous deal.

I’m sure this is the story for most everybody on College Street because we all went there, twenty-five years ago when the rent was nothing and then when I left, the rent was $6000 a month. The property taxes were $22,000 a year instead of $8000 and my insurance had just gone to $26,000 a year. This is something nobody seems to be talking about. Everybody’s insurance doubled depending on where you were in your year and when everybody comes back one of the biggest problems will be how are they going to pay for their insurance. It tripled.

B.K: Before the pandemic, you had been doing events at Revival. Were you responsible for paying insurance for those events?

T.N: I had nothing to do with the selling of booze, so I had nothing to do with the insurance. The only time you must do is if you get an off-sale license, a special party license. Most people who get licenses now have an amendment on their license that allows them to sell booze at weddings or outdoors and in all kinds of other situations. When you do that, you must have insurance. They will probably send a guy from the AGCO to make sure everybody has their smart serve and selling at a price that makes sense. They are prickly about that kind of thing.

B.K: People are nostalgic about the loss of these clubs yet clueless about the difficulties keeping them afloat.

T.N: I can’t tell you how many people would be there on a Friday night and Lou (Pomanti) and the Dexters would be rocking, and Alex would get up and play guitar with them and the place is packed. People would see this and think, wow, you must be making a fortune. I then tell everybody, be here ten o’clock Monday night and watch as the band plays and only three people are watching.

I’ve had people say to me, “Tim, you’ve got to get a bigger place – don’t you wish this was bigger?” I’d say, “No! From Monday to Thursday, I wish it were smaller.”

B.K: Was there a decade when it was impossible to get into the room?

T.N: Yes. What happened was, I never, never had any intention of the place being a live music venue. It was a cocktail lounge with appetizers, a kind of hip place where people came to have a drink and we’d play music on the stereo. There weren’t many places like that especially when you had kind of an international menu of appetizers. It wasn’t a place to come for dinner. Alex Lifeson was my partner, so I needed something for Alex to do. I told him, how about I put together a band that plays on the weekends – plays on Saturdays and you get to play with them. He said, perfect, great!

I phoned up the only other musician I knew and that was Lou Pomanti. I phoned him up because people thought we looked alike, and we became friends. I said to Lou, 'here’s what I want. I want a Booker T & the MGs kind of band, so we need a Hammond organ.' I then asked him could if he play the Hammond organ? He laughed and said, “Are you kidding, I toured the world with Blood Sweat and Tears when I was nineteen and of course I own an organ. We dragged his organ over and he phoned The Dexters. I didn’t know these guys. I didn’t know they were the premiere musicians in Toronto at the time. I’d never heard of Peter Cardinali. I didn’t know he was an amazing musician and famous session guy. And the same with Bernie LaBarge and Mike Sloski. I thought they were some really nice guys who had nothing to do on a Saturday.

They formed The Dexters and within six or seven months we realized we were quite busy on Saturdays and not doing that well the rest of the week. In year two, I started adding other bands. I realized in no time all that the greatest musicians in Toronto wanted to play the Orbit Room because we had a Hammond organ there. The second band I hired was Michael Fonfara who I had been a huge fan of since I saw Jon and Lee & The Checkmates at my high school in 1964. I’d been revering this guy my whole life and here he is coming in and saying he’d be happy to play my club. The same with Doug Riley and Tim Tickner and Gordie Johnson. All I had to do was ask these guys and they’d say they would love to play.

We opened in 1994, so let’s call it the end of ’95 and for the next ten years The Dexters played Fridays and Saturdays for about seven of those ten years. The other nights of the week I had Kevin Breit on Mondays. I asked Kevin to play, and he invented the Sisters Euclid. They played there for seventeen years. I talked to Fergus Hambleton, who is like a revered guy in Toronto and asked him if he’d like to reform The Sattalites and play some reggae as they did at the Bamboo. I gave them Tuesdays and they played there for seventeen years. Even the LMT Connection.

I phoned up Prakash John who had a tremendous band there on Thursdays called The Hiptonics. That was him and Michael Dunston and Jorn Andersen and often Fonfara playing the organ. It was the full-blown Lincolns. He didn’t want to call it The Lincolns because they weren't making any money there and nobody cared. You could have seen something quite spectacular every night of the week.

B.K: How did you get the LMT Connection locked in?

T.N: I asked Prakash. I told him I’m looking for bands that play soul music. He said I should check out the LMT Connection who never play in Toronto because their entire world is Buffalo, Niagara, Niagara Falls area, Hamilton where they are famous and had been around ten years before I heard them. I talked to drummer Mark Rogers on the phone and said the only night I have is Wednesday and he said they weren’t doing anything on a Wednesday. I didn’t know they lived in Niagara Falls and were going to drive up from there. They come up, we talk and I tell them what I can pay them and that I have an open Wednesday and they came and played. Of course, the first time we saw them, our jaws dropped. We thought it was the greatest thing we’d ever seen and there were only three of them. Leroy Emmanuel is an absolute bonafide real deal soul singer from Detroit and Mark is an amazing drummer. They also said Wednesday night was the only night they could play because they had house gigs all over the place. Six months from the start, you couldn’t get in the place. There are still people who say, “Tim, I never came on any other night than Wednesday and was there every Wednesday for ten years.”

If anything, people could go to a bar and see any band play Hotel California not very well yet come to the Orbit Room and see the LMT Connection and be part of this insane party.

B.K: You must have had nights when well-known players from the outside would drop in and say, “This is amazing. How is this happening here?”

T.N: All the time. The one that sticks in my mind the most was when Paul Shaffer was there. Prakash’s band The Hiptonics I’m guessing knew each other or maybe had something to do with the Blues Brothers 2000 movie and he came up to me and asked, “How are you doing this? How are you getting a tremendous band play in this tiny club?” I said, “I don’t really know other than these guys like to work, and they like to work for me.” Located in New York and playing clubs in New York I bet he thought, wow, this could never happen in New York because there is no way on earth the players in New York would work for $40 a night or so. What he was saying I’m thinking was, how could you afford to have these guys play here? I said, “I pay them what they ask and that’s how it works.

B.K: Even the most renowned and well-documented clubs were always cutting corners for survival. There was a long-distance between a Birdland which was essentially a lunch counter to a Café Society with high-end patrons who’d drop a hundred dollars for a table in a shaded corner or down the front.

T.N: I’m certain running a club for twenty-five years I had essentially the same problems as a Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club or a Blue Note Jazz Club had. How do we pay the bands if nobody shows up and pay them what they are worth? It’s unbelievably tough. Twenty-five years and I still had people argue with us at the door about paying the cover up to the very end. “Hey, there are seven of us, would you let us in for $50?” No, how can you not understand the place only holds a hundred people and there are ten guys in the band like an Oakland Stroke or Pretzel Logic? I want to pay each guy at least a hundred bucks and there’s no way I can let you in. They constantly argued with me.

B.K: I’m looking at the club scene after Covid with the rents and insurance and wondering how is anyone going to open a club?

T.N: I think every bar in Toronto is going to be up for sale or rent. I have no idea how or why everybody’s hanging on. The rent at the Horseshoe is $50,000 a month.

B.K: The rent at the Phoenix is $45,000 a month?

T.N: Yes. It’s been a year with zero income. Who is paying that and how are they paying that? If the federal government is paying half to the landlord and won’t give me one cent, I will be very angry.

I did this GoFundMe because I got tired of filling out the forms for the government’s small business money and being told I don’t qualify. After all, I was lucky and got out of my lease and didn't have an actual location anymore but was still doing my concerts. I still ended up with all the bills everyone else has but didn’t get any money from the government.

B.K: More on your GoFundMe.

T.N: My GoFundMe has stirred up a lot of interest and people wanting to be my partner and open a new live music bar. These are people who have tons of money. Many used to come to the club and say they have the money, the love of the music, and have me and my connections. I have five or six complete single guys and groups of people that want to help me open an Orbit Room. I’m considering it and I’m also 70 and wonder how badly I want to work that hard, but I still have to do something. There’s no way I can retire.

B.K: Just think of yourself as fighting Joe Biden, the club impresario.

T.N: I ask you. A year from now how badly are people going to want to go to a club and hear a band of tremendous musicians play Steely Dan covers? Is anybody going to care anymore? Or play songs that your dad liked?

B.K: Honestly, so many great new bands of multiple genres have surfaced this year. They are under the radar. I hear them all the time. It’s their game now. I also think back to what happened with my brother before he passed. His age group of music fans attached to the sixties found a venue to hang out, play live the music they love and socialize as older adults and packed the place. They will be there until the last dance.

T.N: This is what I’m terrified about telling my investors. Let's do this or that. I was 45 when I opened the Orbit Room and even a little long in the tooth then for that kind of effort. Those were 200-hour weeks. The 35-40-year-old who opened that club is now 70. Can I count on them at all? What are the chances?

B.K: Hire a young staff and put them to work and you buy a nice suit. Nod, smile and shake people’s hands.

T.N: I know I can get those folks out if I put two of those bands together; Oakland Stroke and Brass Transit in a place that holds 500 and have the show start at eight and finish at ten. To have one of those bands play at my club every week, not a chance.

Contributions to the Orbit Room's GoFundMe campaign can be made here