A Conversation With ... Joshua Redman

This renowned jazz tenor saxophonist was just emerging as a bandleader when he played Toronto’s du Maurier Jazz Festival in 1994. Bill King’s revealing interview with him there has been retrieved from the archives.

By Bill King

It was May 1993, and I was invited down to the tropics to cover the St. Lucia Jazz Festival. This was my fourth year of exploring the Caribbean, all courtesy of local tourism.

The hotel we were staying in featured a jazz band on the back veranda. This was no ordinary band of weekend warriors, but one chosen and arranged by the festival of the brightest new faces in American jazz. Bassist Christian McBride, New Orleans, Donald Harrison on alto sax, trombonist Steve Turre – a wicked front line also featuring a young tenor saxophonist I’d never heard of before, Joshua Redman.

As great as each soloist was at picking up where the other left off, it was Redman who astonished the audience. It was as if the other players were playing the overture and acting as background players to Redman. We anticipated Redman’s every solo. But, as with jazz, it’s guesswork. Who goes first, and when does our guy return.

A year later, I pulled Redman aside at Toronto’s du Maurier Jazz Festival for a sit-down. What struck me about this conversation was how universal his responses were and how he spoke to every young, gifted, dedicated newcomer and musician, no matter the style or the genre of music.

Redman was 25 at the time of this interview, graduating from Harvard University in 1991 summa cum laude in social studies. The years in between have been remarkable. Now at 52, Redman is the artistic director of roots, jazz and American music at the San Franciso Conservatory.

It’s 1994!

Tenor saxophonist Joshua Redman blew on to the jazz scene a couple of years ago with his self-titled album. His second Warner Brothers effort, Wish, featured Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins and solidified his position as one of the most exciting new players in the genre. But Redman has taken an unlikely;y route as a jazzman. The son of tenor great Dewey Redman had no intentions of becoming a professional musician. Instead, he enrolled and graduated from Harvard and then applied to Yale law school. Deciding to explore music for a year, he deferred his admission and won the Thelonious Monk Institute’s prestigious jazz saxophone competition. Since there’s been no looking back. Redman’s latest Warner Brothers release is entitled MoodSwing.

Bill King: Has it been a smooth transition from sideman to leader?

Joshua Redman: It’s been very smooth. It hasn’t been a complete transition because I’ve integrated my sidemen appearances with leader appearances over the past year. Granted, what I’m primarily doing now is leading my group, but even as recently as April of this year, I did a week with Clark Terry. Before that, five weeks with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra. Last year, I was working with Pat Metheny. So it isn’t as though I was a sideman and suddenly a leader.

Being a sideman is something very important to me. I’ve held off on many leadership opportunities to maximize my experience as a sideman. I’m very proud that I have been able to balance both aspects of my career so far.

B.K: I’m always impressed by the young players who come up through Betty Carter. She schools them.

J.R: You’re right. Unfortunately, there isn’t the same thing for horn players. Betty Carter is a great training ground for rhythm section players, but the school of Art Blakey was it for horn players. I regret never having played with him, although I have played with people like Charlie Haden, Jack DeJohnette, Paul Motian, Elvin Jones, Clark Terry and Milt Jackson.

I’m trying to continue those experiences. If one of those guys calls me, I’ll do anything to make it. They will not be around forever, and the knowledge they have you can’t get anywhere else.

B.K: Did anyone ever say, “Joshua, hold it there a minute?”

J.R: Most of the older musicians I’ve played with have nothing specific to say about the music. With all the masters, I’ve learned through the act of playing, not from them sitting me down and explaining things.

Music is a very intuitive thing. I’m not saying you can’t express the ideas literally or verbally, but most brilliant musicians rely on their intuition, and to learn from them, rely on yours.

They teach you about the broad things, the intangibles, communication, sharing your soul with other musicians, playing from the spirit.

I haven’t had the experience of someone saying you need to do this or that. Of course, if someone were to tell me, I’d be happy to take their advice, but most of the musicians I play with share musical wisdom that transcends words.

B.K: Are you feeling an undercurrent of pressure from all the exposure?

J.R: No, I don’t feel any pressure because it doesn’t really matter to me. I’m happy to have the opportunity to be out there playing music and making a living. I pressure myself. I was putting pressure on myself when I was sitting at home with no gigs. I couldn’t stand the way I played back then and still can’t stand the way I play now. The surrounding hype isn’t that important. It could never set standards higher than those I set for myself.

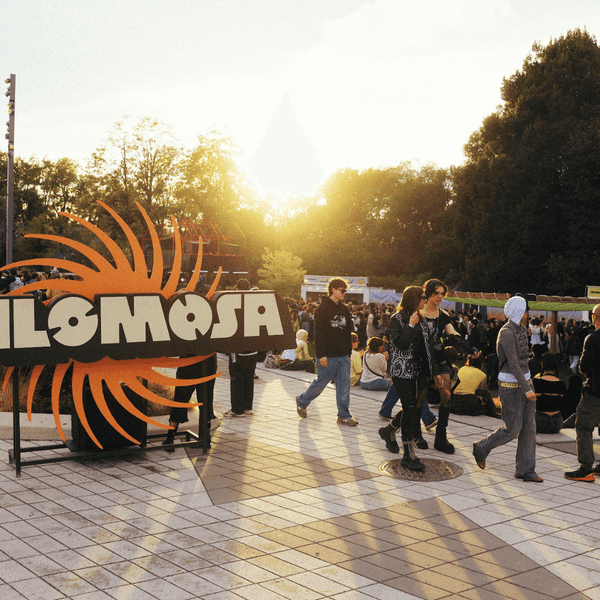

There is a certain amount of physical pressure from having to perform so often. This situation with du Maurier is ridiculous. They’ve got us playing three times in about 36 hours. Today, we’ve just played an hour-and-a-half show and then we have to play three hour-long sets. That’s overkill. I’m very honoured to be part of the Toronto Jazz Festival, and I love this city, but if you demand too much from a musician, there has to be a drop in quality. It’s physically draining.

I think few promoters, agents, or managers clearly understand the spiritual and emotional energy it takes every time you get up there on the bandstand. Granted, jazz musicians don’t hold down nine-to-five office jobs, but promoters sometimes think an hour-and-a-half on stage is equivalent to, say, an hour-and-a-half of sitting in an office answering telephones.

The emotional and spiritual energy that goes into that hour-and-a-half of performing can only be done twice a day at most. But, ultimately, I take responsibility because I agreed to this.

B.K: It’s been said that a musician will expend an equal amount of energy in performance as football players banging heads on the playing field.

J.R: Oh, definitely. I’m striving to play an hour-and-a-half show entirely concentrated on every aspect of my music and to have my musical soul totally focused. That’s something I’ve never been able to achieve. To be that tuned in when I’m playing and to what the band is doing. That total concentration is very complicated to achieve.

B.K: This band must give you plenty to think about.

J.R: We have a great rapport. I can’t wait to stop soloing, so I can get to the side of the stage and listen to them. I get an education just hearing them play. I’m lucky to have three of the greatest young musicians playing today in my band.

With jazz, you should be tuned in all of the time. Also, with the amount of predetermined music being less than five percent, it demands a lot of improvisation.

B.K: There are critics who have jumped on your bandwagon who may abandon you as you expand your horizons. Does that bother you?

Everyone won’t like what you do. I’ve been fortunate to have very few negative comments about what I do. That can’t continue. A lot of what happens to you in the world of criticism has nothing to do with what you’re doing musically.

I think when you reach a certain level, some critics feel an obligation to start trashing you. There’s an inevitable backlash against any artist who has reached a certain level. It doesn’t worry me. I’m prepared for it. Sometimes it worries me that I’ve received so many favourable reviews, yet I don’t want them to stop.

B.K: Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul and Miles Davis invested in popular culture, cultivating a new sound. Herbie dug deeper into the idiom, yet some radio programmers see their roles as curators in a jazz museum and downplay his later works.

J.R: Anyone who would say Herbie Hancock’s stature as a jazz musician has been diminished because of the distinct music he’s done actually diminishes the stature of themselves in my eyes.

Jazz, by nature, is expansive music. It is about improvisation, originality and personal expression. There is a need to get out whatever you hear inside of you. Jazz has always been outward looking.

B.K: Do you think the media actually hear what’s being played or are they more influenced by the promotional hype?

J.R: There are very few Herbie Hancock records where I say there is a drop in the musical standard. Everything he’s done is first-rate in whatever idiom he’s explored.

B.K: Miles always moved on.

J.R: But that also doesn’t mean every jazz musician is required to experiment with pop styles. A great jazz musician is someone who remains true to their musical soul and vision and plays music with honesty, integrity and expressiveness. From different musicians, there are going to be different answers.

For someone like Herbie, it means experimenting with as many styles as possible. For me, it means that too. For someone like Wynton, it means working within a certain acoustic framework. He’s taken a lot of chances and really pushed the limits. I don’t think he’ll ever experiment with pop styles, but he won’t be a lesser musician for it. It’s all about you, what you have to say and how you define the parameters.

B.K: Wynton’s composing and arranging have become a central component of his arsenal.

J.R: I think he’s the greatest composer to come along in a decade. People have listened too much to things he says and pay too much lip service to his image. That’s one tragedy of the jazz world. There is too much attention to images, theories and intellectual arguments about the values of jazz and what makes up jazz, and not enough attention is paid to the music. If people only close their eyes and listen to Wynton, they’ll find that he is incredibly innovative.

B.K: For a segment of players jazz, it’s about deconstructing the form.

J.R: Jazz is about improvisation and it can take many forms. Since Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor and Anthony Braxton got rid of harmonies, chord changes, set meters and some forms in the ‘60s, some think there is no looking back.

I like some of it, but jazz isn’t like a road race going down a path, never looking back. Jazz is being conscious of tradition and the music of the day. For some, it means pushing the limits in a theoretical sense, but for me, it means experimenting with a lot of different styles.