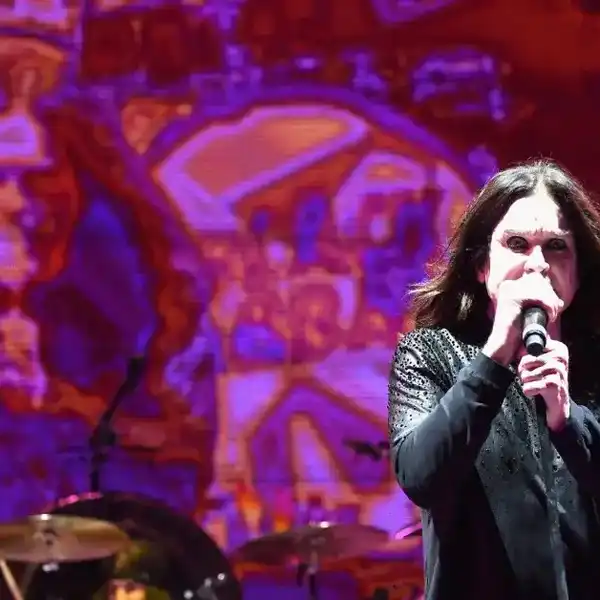

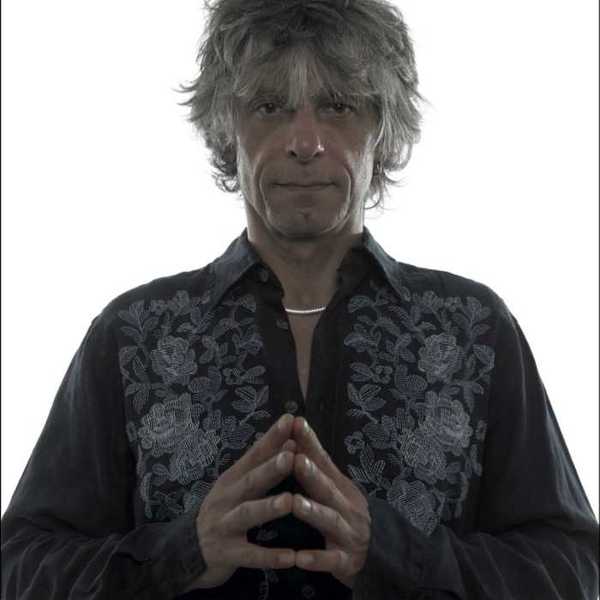

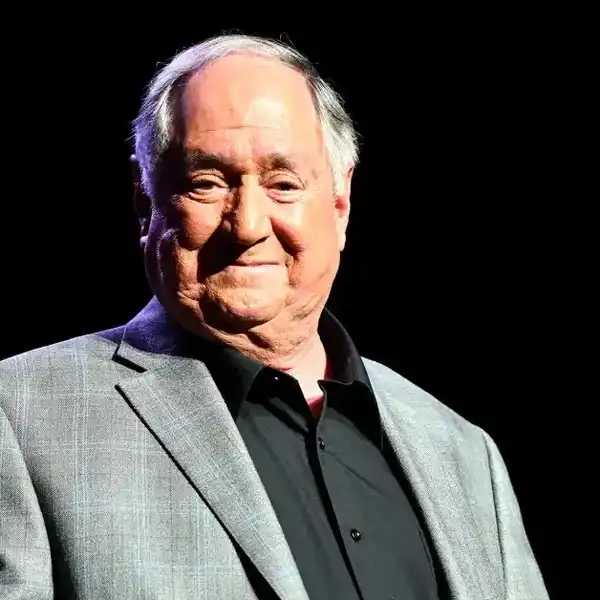

A Conversation With ...Danny Weis

The veteran guitarist reminisces about his musical upbringing, his earlier bands Iron Butterfly and Rhinoceros, and work with Bette Midler and Lou Reed.

By Bill King

In the mid-seventies, I hired guitarist Danny Weis and drummer Pentti Glan to play a few gigs up north with my band. These guys were already rock stars, and there's nothing glamorous or redemptive about driving untold hours in sleet, rain and blinding snow for a handful of dollars. It was all about the players I had assembled - in fact, on stage, they were "force-ten" energy.

After gigs, Pentti insists we stop along the way for drinks and laughs - most times, a dining room in one of the many small-town hotels doting the landscape just before closing time. It's one in the morning, and we're facing the long haul back to Toronto. Pentti holds court, narrates road stories, pours drinks then turns the after-hours sessions into an additional gig. We arrive home somewhere past five in the morning.

I recently connected with Danny on Facebook and caught a series of at-home videos he's been producing and posting and then it hit me, this guy is crazy good. I remembered the slashing rhythmic style, the cutting lines and polished tone of his playing, all steeped in R&B and country, from those gigs.

Dan then turned my attention to a recording he made with a stellar group of Toronto players in 2006, Sweet Spot. The late Richard Bell, Lou Pomanti and former bandmate Michael Fonfara keyboards, Rich Brown bass, Jorn Anderson drums, Vern Dorge sax and others. It's jazz, funk, blues, fusion jazz and a bit of country. Above all, the playing is brilliant. I cornered Danny this week, and we talked.

Bill King: How's life, Danny?

Danny Weis: We are good and blessed. We live in the woods literally in a small town named Markdale, which is about a half-hour south of Owen Sound. We moved here in November 2016.

I'd been back and forth from California to Canada over the years, the last time I went down was 2009. I hadn't planned coming back at all, but things changed, and we looked at our lives, our age, the future, finances, homes, but mainly because we have some family here. My uncle passed away – we'd gone down there to take care of him – we started talking about it, and it made more sense to come back up here. It took us about six months to find a house. It's quite beautiful, living in the country.

B.K: You grew up in San Diego county.

D.W: I lived in El Cajon twenty miles inland.

B.K: Our fathers have much in common – both played guitar and had friends who were elite jazz guitarists. My dad Jimmy Raney – yours, Barney Kessell.

D.W: Barney Kessell used to come to the home, and I'd sit there in awe watching Kessell trade licks with my dad Johnny Weis, a country/western swing player. My dad was no slouch and every bit as good as Barney. They'd trade licks because they had the stuff to share. They were friends. I got to watch that.

My dad was certainly a mentor and a friend, more of a musician friend than father – a teacher. He used to come to my gigs whenever he could. He'd be in the audience, giving me a thumbs up and a nod. A couple of times, I sat in with his band. I used to watch him at the Bostonia Ballroom in El Cajon, California. That's where I saw him back people from the Grand Ole Opry. People like Tex Ritter, the Collins Kids, Joe and Rose Mathis, even Johnny Cash.

From age nine to twelve, I didn't play guitar. I took drum lessons for a while, just wasn't sure of what I wanted to do. At twelve, I picked up a guitar and thirteen making money at it. I worked every week all through school and bought my car and all my equipment.

If you see pictures of my dad, his hands look identical to mine - the way I hold a pick, the way I hold a guitar, it's my dad. He showed me some important things. He didn't think it necessary to show me a whole lot because he didn't want me to end up sounding just like him. He told me, "I want you to sound like your self and have your sound, and I'll always be there if you need anything," and he was right.

He taught me the basics, and we learned a few songs together. We learned East of the Sun by Johnny Smith – a beautiful jazz tune, and the chords were really hard to play. I could barely stretch my fingers across five frets. We had trouble catching this really fast lick, so we slowed it down from 33rpm on the record player and sounded like" Rrrrrrh" really hard to get, but we got it. His record collection was Johnny Smith, Tal Farlow, Herb Ellis – all the jazz guitar players.

B.K: You co-founded Iron Butterfly.

D.W: I put it together with Doug Ingle. I was seventeen and Doug and I had a band that started as The Progressives, then Jeri & The Jeritones because the lead singer was named Jeri, of course, the Palace Pages. Together Doug and I got a couple of new players and put together Iron Butterfly. We were playing a place called the Palace in San Diego then decided we were moving to Hollywood. We got another singer Darryl Deloach who has since passed away. Darryl had a big ole hearse, and the band got in the back of and drove to Hollywood. When we first started, we were playing a place called Bido Lido's on Cosmo Street in Hollywood. We had no money, so we figured we'd let the music be our food. We stayed in the manager's office – it was pretty slim living sleeping on the floor. That's where it started.

Iron Butterfly got pretty big quickly. I really enjoyed myself; it was a change and suddenly in Hollywood I shared the stage and partied with the bands on Sunset Strip. Gazzari's, I played the Galaxy a lot, the Sea Witch, the Troubadour, the Roxy.

B.K: I saw your band Rhinoceros play the Kaleidoscope initially the Moulin Rouge, then Hullabaloo Club. They had this weekend series that ran late evening. I caught the Chicago Transit Authority's Hollywood debut and following the set a feature film – on this occasion The Chase with Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda and Robert Redford. Your night, I can't recall the film, but I do remember how much I was impressed with you and your band. And then you played Apricot Brandy.

D.W: That tune has got a lot of mileage to this day. I still get checks in the mail. It reached #45 on Billboard and Cashbox and for an instrumental – that was pretty good back in that day. They used it a lot for commercials - come to the racetrack Saturday night, and it would be playing in the background.

B.K: We knew the distinctive sound of Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, and Jimmy Page, then you come along with this new guitar sound and that opening riff cuts, much the same language and thoroughly refreshing.

D.W: Like my dad wanted me to do, I didn't take that from anybody, it just happened. To go from Iron Butterfly to Rhinoceros - I did play a lot of R&B in my teens. There were a lot of big bands, 10-12 pieces in the San Diego County – Mexicans and black. I thought it was so cool and wanted to be in bands like that – The Centurys, the Nomads. They had four or five horns, big full bands and wore overcoats and stuff. I played James Brown all through high school as well as standards at private parties. The "chicken pickin'" thing came from watching all the pedal steel players when I was a little kid, and it stuck.

B.K: My side of the world it was Lonnie Mack. It was about the region of the country you lived that determined the sound.

D.W: I wasn't influenced by guitar players that much, and it may sound strange to say – I am one. I listened to saxophone players a lot for phrasing. I used to listen to King Curtis and keyboard players like Billy Preston, who I listened to all of the time. I also listen to drummers. I didn't have that many albums of guitar players. I would take what I got from other instruments and apply that to the guitar. I'd play rhythm on the guitar and copy a clavinet riff. Or I might be playing a drum rhythm on the guitar with the chords. It sounds strange, but I don't have a lot of guitar players I can say I learned from other than Joaquin Murphey who was one of the best pedal steel players in the world. Another guy, Al Gordon, who was a phenomenal jazz pedal steel player. James Burton sticks out. Wait, the Ventures!

When I was thirteen and Walk Don't Run came out I was proud I learned all of these albums. I was happy I got a typewriter for Christmas and was so proud of all the songs I learned and typed them out, but that didn't last long as I turned from fourteen to fifteen and playing more ballads. I listen to more guitars players now than back then.

I also want to learn – to keep growing. I play every day of my life. I have to; I'm miserable if I don't. At 71, I get stiff if I don't play.

B.K: More on Iron Butterfly.

D.W: I left the band before In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida happened. I was on the first album called Heavy. I co-wrote or wrote half of the album. There was some internal nonsense that happens in every band, and I decided to leave. Then Rhinoceros. They regrouped. I still have old posters from back in the day. I've got one from the Galaxy.

B.K: Wasn't that great – all of the great artwork.

D.W: And a great time musically. The 60s' and 70s' you didn't have to sound like anybody. There were so many different styles that were all OK.

B.K: I remember your times with Alice Cooper.

D.W: Welcome to My Nightmare.

B.K: Then, The Rose. You and Pentti Glan – that was a big story around here.

D.W: That was huge in my life. I got a call in early 1978 from Paul Rothchild, who has since passed on. He was the producer of Rhinoceros. He also produced the Doors and Janis Joplin. He called me one day and said, "I'm doing a movie with Bette Midler. Do you want to be in it?" I said, "No, sorry." Of course, I want to be in it." He wanted me to be the bandleader and musical director for the movie. He said he had a few players and asked if I had some. That took a year for my life to film that thing. I really enjoyed it because I'd never been in a movie before. It was a big learning curve, and I had to work hard.

B.K: She's an amazing woman.

D.W: She was really terrific and such a sweetheart. She was always concerned that she wasn't able to sing that genre because she did cabaret. It was so different for her that when she finally did it, she understood she could do this. She did a hell of a job and hell of a job acting too. When I saw the movie after it was finished, I was so proud to have been in it. I thought it was a good movie and it was then nominated for five or six Academy Awards.

Right after that, Prakash John called me and wanted me to move to Toronto and join The Lincolns. And I did.

B.K: Lou Reed?

D.W: 1974 – I was the bandleader for that project. The album we did was called Sally Can't Dance.

Interesting tour. When we first got together, Michael Fonfara and myself and Prakash had played together before. It was always R&B funk bands. We started taking a couple of Lou's songs and turning them into R&B songs just joking around and having fun with it, and he said, "What's that?" We were laughing and stuff, and he says, "No, no, no, I like that – let's do it that way." Honest to God, the whole album turned R&B/rock, and we toured that way too. We did every song with a bit of R&B funk flavour under the whole thing, and we had a ball with it, and he likes it. The only album he did with that style.