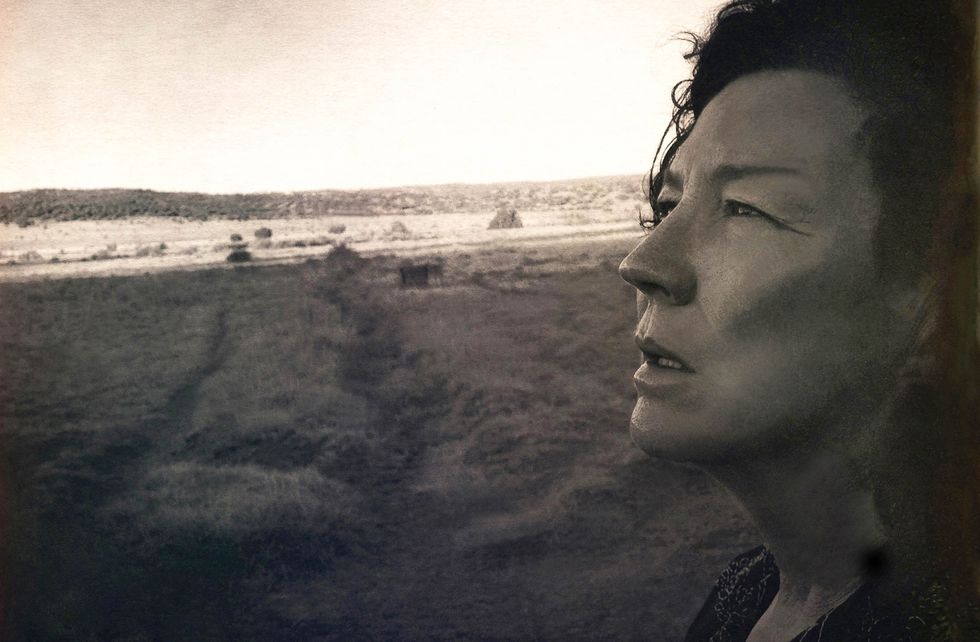

A Conversation With... Deborah Samuel

The noted photographer and music video director was a crucial figure on the ‘80s and ‘90s Canadian music scene. Now a resident of Prince Edward County and focused on her deep love of animals, she has published a series of photo books - Dog & Pup and The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds. She recalls a fascinating career here.

By Bill King

It was the early '80s, and Toronto was in transition - newly aware of an inventive group of emerging artists: Kurt Swinghammer, Lorraine Segato, the Parachute Club, Leroy Sibbles, the BamBoo Club and Queen Street West the centre of activity and young photographer/videographer Deborah Samuel, a noteworthy participant in that scene. Samuels was behind the lens to capture portraits and album covers for Leonard Cohen, Margaret Atwood, Rush, Alannah Myles, Queen Noor of Jordan, Alanis Morissette, Tim Burton and saw her superb imagery appear in the pages of intercontinental magazines: GQ, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Spin, Zapata, Images Magazine and Entertainment Daily.

Samuels eventually abandoned the LA scene and relocated for a long stretch in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Now a resident of Prince Edward County and focused on her deep love of animals, Samuel has published a series of photo books - Dog & Pup and The Extraordinary Beauty of Birds. We talk!

Bill King: We go back to nineteen eighty-four. I was determined to finance my first jazz album. I toured a record pressing plant, recorded the album then went in search of artwork. I think it was artist Heather Brown who said get with Deborah Samuel. She's right for you.

Deborah Samuel: I remember the faces.

B.K: The cover shots of bassist Dave Young, saxophonist Pat LaBarbera and myself. I remember walking into your studio and thinking; this is something completely different. Are you a graduate of Sheridan College?

D.S: Yes, in 1977. The fascinating thing is I had a good friend who had been through the photography course at Sheridan - he wasn't actually in my year, he was a member of what became the band The Kings. And that's how I started in music. They needed promo shots done. I was in college, and I had no idea I was even going to be a photographer when I left because I didn't want to be a photographer. I love photography, but I didn't know how to become one. Then the band got a record deal, so I did their album cover. And that's really how it happened. The opening was there, and what I saw was it afforded me a creativity that I couldn't imagine anywhere else in any other part of photography at the time.

B.K: Everybody sees differently. To come up with something unique, you must have a clear idea - a vision and consider your surroundings in a way others don't.

D.S: True. That's an interesting question. What do I draw from? That's interesting because that's very complex for me, that question, only because I work in so many areas. The reason I started to work in so many areas was that I always want to push my work creatively. So if I stayed just doing album covers, I wouldn't be able to express what I wanted to do. So I went into fashion, which helped the album cover. Then I went into editorial portraiture, which is all connected. It allowed me to creatively do my best work in all fields because I wasn't wedged into one field. What did I draw from? If I was working commercially on a project, I listened to what people were looking for. And then I trust my intuition. I let it rip in my head - the ideas they flow, and then I start to see what it is I should be doing. And then I trust that's what I should be doing.

B.K: I think you kind of borrow from everything.

D.S: I do.

B.K: I was thinking the early days of Annie Leibovitz and Rolling Stone Magazine, she had freedom.

D.S: Yes, absolutely. That's what I was doing was giving myself freedom. At the time, I think Canada had 24 million people. You had Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, the three major cities. There are always new people coming on the scene, so it keeps you fresh in all of those areas if you're moving in lots of areas. A lot of people can't do that or don't want to do it. They like to be categorized - they only do product or only, rock and roll or whatever, and that's fine, but for me, creatively, I had to move between a lot of areas to feel the freedom to do what I had to do.

B.K: When requested to do portraiture, would you reference the work of other photographers? Someone like a Richard Avedon?

D.S: A past agent of mine told me a story where somebody came in, and they'd hired me to do something, and then they called her back, and said, can she shoot like Ansel Adams? And twice at the time, I said, don't you dare ever ask that question. You know that I'm not Ansel Adams. If you want Ansel Adams, get Ansel Adams. I'm a little unexpected in my work. The thing that I find interesting when there are a lot of budgets and things are just flying, like in the 80s and the 90s, what ends up happening is people feel more empowered to be creative and to be different and do different things. I was in the right place at the right time for sure with that. When budgets get tighter, and economics and policy and world policy and politics and people are starting to feel all of that, they start playing it safe. I did a lot of hand painting, but, you know, that goes in and out of style. That's for sure. I just enjoy making the picture that I see in my head.

B.K: Black and white versus colour?

D.S: I'm more known as black and white, but I cross all mediums.

B.K: When young, did you study those bold black and whites in Life Magazine?

D.S: I used to as a child. Interestingly, I collected, and there were no photographers in my family. I had a Kodak Instamatic, and I would do crazy things. I'd run up to the drugstore in the little village I grew up in. They'd process, and it would come back, and it was like, wow.

I was living in Ireland at the time. My family had moved to Ireland, and I did the art school foundation year. You'd do a little bit of sculpture and painting and drawing and things like that. There was a three-day course in photography, and they did darkroom, and that was it. I went, wow, I love this.

B.K: You processed film?

D.S: Yes. But it was so short. I wanted to come back to Canada, so I applied to Sheridan College because somebody told me to apply, and they were offering a lot of different art courses, and one was a creative art course. And that was again, sculpture, ceramics, cause I thought I wanted to be in ceramics and I applied to that, and they canned the course and wrote back. I was then an international student, and they said, do you have a second choice? I said I'll try photography. I did the two-year program and came out of the two-year program, graduated and still didn't want to be a photographer. And then basically I had to find a job. A friend of mine introduced me to Larry Miller and Greg Lawson, who were photographers who needed a printer. And that's how it started for me because I could see how they were making a living doing photography and printing.

I loved the darkroom, but I must admit that after 40 years of a darkroom, I started to feel health stuff going on. When I say that, I did always have adequate ventilation, but you can't have enough good quality ventilation. I then became proficient at Photoshop and more digital work. I still work in both. I still shoot film on specific jobs, certain projects - the dog work is always film, and then I shoot digitally on other things. So I work both ends of it.

B.K: Do you use Lightroom?

D.S: No, I use Photoshop. You know, the thing that's interesting about Photoshop and what I always say about Photoshop is the problem is people don't know when to stop. They go over the cliff. I know when I'm going over the cliff, and I have to start backing up, I've done enough. That's an intuition thing, too. That's the issue with staying creative, and that's why I moved between a lot of different subject matters. And I still do. I like that I can do it. What ends up happening is people follow a particular trend that becomes less acceptable and wanted.

I found that in my work, like when I was doing fashion, I shot a lot of grainy work. I loved shooting that. It was very stylistically what I was doing. But I also found that people were coming to me saying, we want your grainy work. I became like the "grain queen" of Canada in fashion. And I said, got to stop it and I moved into another area. And then I took all those people that had liked to work with and tried to get them over here. I just kept moving in different techniques so that I stayed fresh. In creativity, it is the key.

B.K: With live rock concert photography especially photographing heavy metal bands – the images are oversaturated, intense clarity and most depict artificial over the top stage antics. It's what pop magazines want.

D.S: You have to be a little careful that your audience still recognizes who you are. You know, it's always a gentle move into a new direction that's never entirely, 180 degrees.

B.K: What was the first 8X10 you printed?

D.S: To be honest, it probably would have been an elderly couple who lived down the road from where I lived in Ireland. Jack and Jamie. They were old and lived in a little cottage - brother and sister who'd lived together all their lives. And that was my first.

I loved taking pictures of people, yet I never thought of it ever as a career or as something important. I just enjoyed it.

B.K: Were you ever apprehensive about approaching people?

Well, no, not really. I did do that when I started at Sheridan College. I don't do it so much now, but I'm so fast at it now the pictures taken before they even realize it.

Back to printing. I just started not to feel well, and I'm OK from all of it. I didn't make that jump into digital, and I have to tell you that sitting in the sunlight, being able to do this stuff and using Photoshop the same way I would have printed, burning, dodging and spotting was it. I don't do the complicated stuff, you know, moving pictures and people around, things like that. That's not who I am. I can sit in bright sunlight in the fresh air. But there was something magical about the darkroom, going in and nobody could come in, and it was dark, and you could play your music with headphones and print away.

B.K: Dogs & Pups. What is it about dogs?

D.S: I've always had dogs. I love dogs. My parents were horse people, and we at all times grew up with horses. We constantly lived in the country. We always had five dogs and cats and, you know, ten horses - three horses, four horses, whatever. They're an integral part of my life, for sure. I love dogs.

B.K: I was working in my office yesterday, and I happened to look down and see both of our dogs staring at me. I thought about that and then asked, "Do you two have something to do?" It was obvious it was me.

D.S: I've always been close to dogs and then started the dog project. I stopped working commercially in 2000 because I'd always run dual careers of my artwork and shows and galleries and then my commercial work. The difference with me is the commercial work was never really that commercial. It was always more thought-provoking, creative work. That's why people would come to me. They wouldn't come to me to do the straight work. And I wasn't good at straight work. I was better at, you know, more cerebral.

What ended up happening was I had three dogs. I had a rat terrier, a yellow lab, and a boxer. I started to notice that every time something was going on in the house, all three reacted differently because of their breed. I then initiated this project where every dog I saw I wanted to photograph, and I wanted to try to figure out the breed differences, the emotional breed differences between dogs. It's not you know, the breed group. It's also the breed within a breed group. And, you have hunting dogs. You have guard dogs. But they all are bred for a specific purpose, and they all react differently. And this whole thing just started. And I've been shooting dogs for 20 years now.

I had a little Jack Russell, and what I found interesting was Jack Russells are bred with a black or brown ring around the bottom of their tail at the base. It's really for when they go down holes to grab rabbits or whatever it is; they're going to go down to capture – so the owner, the farmer, the hunter, whatever, doesn't shoot at their dog thinking it's a rabbit. Every breed is explicitly bred for a function.

B.K: You made the transition from photography to video as a part of the MTV generation. Tell me something about that.

D.S: It was a natural progression, I think because I was shooting so many album covers. When videos came in, music videos, I knew a lot of the people. A company came to me and said we'd like to develop our music video department within our company - would you like to do it? We'll help you get started, which was Schultz's Productions at that time. I knew a lot of people and people were transitioning into music videos. Every artist I was doing an album cover for needed music videos. It only made sense because, in a lot of cases, I was helping sort of look at an artist. So they wanted that same look in a video - they wanted to follow through.

B.K: Who were some of the artists you worked with?

D.S: Parachute Club, Alannah Myles and Luba. This goes way back also to Michael Damien. I did a lot of artists at the time, and it was mostly in the 80s and 90s.

B.K: You live out east?

D.S: I am in Prince Edward County. I love the country, but a lot of that comes from me living on a ranch in New Mexico for fourteen years.

B.K: Why did you pick New Mexico?

D.S: I lived in California for twelve years before that and L.A. for almost three years, working in entertainment. I got married and lived in Santa Barbara for about ten years. And then we decided to move out of California, and we moved to Santa Fe, not knowing anybody. We went there for a holiday and liked it and went, OK, we're moving. And that's how most people end up in Galisteo near Santa Fe.

I just loved the light. I loved the landscape. I loved how alone you could be. Last three years, I was living on a thousand-acre ranch and helping look after twenty-six Spanish mustangs that ran free on the ranch. It was something, and I could do my work, my artwork. I was alone with all of it.