Canadian Music Hall of Fame Profile 4: Cowboy Junkies

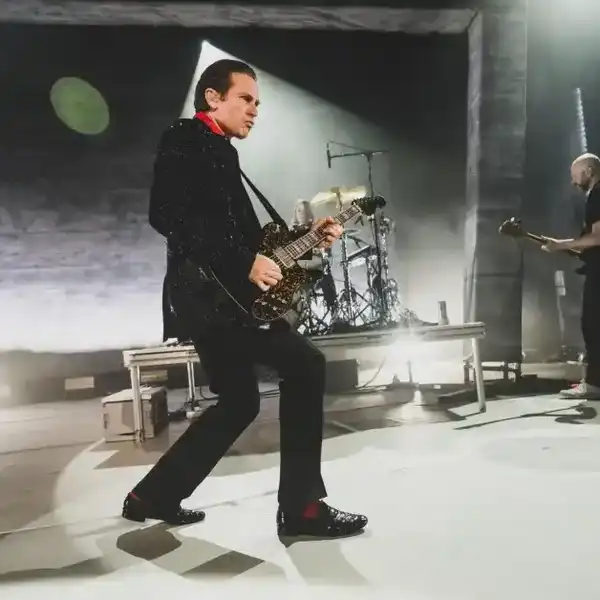

In the final instalment of our four-part series on HoF inductees, we talk to guitarist and producer Michael Timmins about the group's long career, his approach to recording, the halcyon days of Toronto's club scene, and his ongoing love of vinyl.

By Bill King

At Calgary's Studio Bell, home of the National Music Centre, on Oct. 27, The Canadian Music Hall of Fame inducted four legendary Canadian acts to its house: Andy Kim, Bobby Curtola (posthumously), Chilliwack, and Cowboy Junkies.

The Canadian Music Hall of Fame, established in 1978, recognizes Canadian artists who have manifested themselves here at home and or abroad, including Anne Murray, Joni Mitchell, k.d. lang, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Oscar Peterson, Rush, the Guess Who, The Tragically Hip, Shania Twain and others.

Cowboy Junkies, amongst the class of 2019, established themselves as one of Canada’s leading voices with the release of The Trinity Session, November 1987. I caught up with producer/musician/songwriter Michael Timmins and dug into the band’s storied past for this insightful interview.

Bill King: NYC has played a significant role in so many musicians lives. What was it about that music scene that pulled you in?

Michael Timmins: NYC and London were always our music Meccas growing up, especially during the punk days of the mid/late 70's. There were other cities with great scenes during that era (including Toronto and London, Ontario), but NYC was “the place to be” (RIP Keith). We would often take road trips there for the weekend to see as many bands as we could, pile into one room at The Iroquois then drive back the next day to T.O..

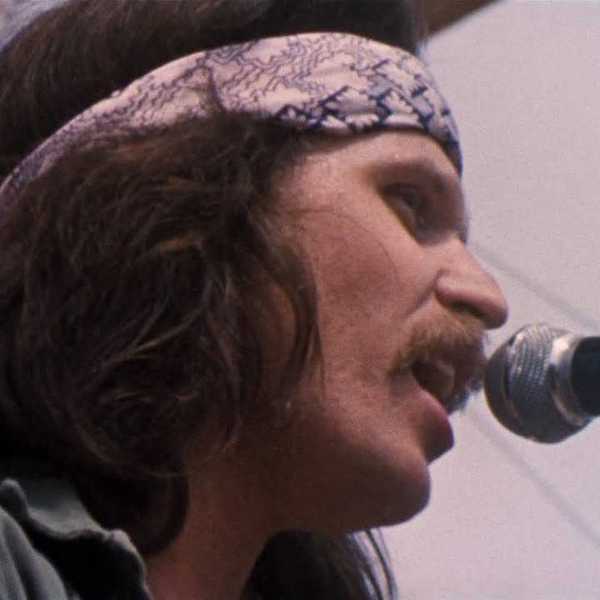

B.K: Each decade NYC rallied around a sound – something innovative and eclectic – 52nd Street and jazz during the 40’s and 50s – psychedelia, folk and experimental jazz during the 60s and 70s – punk during the 70s. Is there an era you would have preferred to have been a musician living there?

52nd Street in its heyday. My Dad has some fading memories of seeing Thelonious Monk and a few other titans. I would have given anything to see the full-on Basie Big Band doing its thing. But I wouldn't pass up a time travel opportunity to spend a weekend at the Fillmore East.... I was living there in 1980 so I at least have that notch in my belt.

B.K: Working in a record store was as close as one could get to the feel and excitement of holding an LP. Do you still buy vinyl? If so, what could we find in your library?

Vinyl is all I buy these days. As a music fan I'm so happy it's back. I love the tactile experience of playing vinyl and the way it forces you to slow down and pay attention. It's amazing to watch my kids get into vinyl and watch how their relationship to music has changed because of it. I worked in a record store in London for three years in the early 80's (at The Record and Tape Exchange), which was a great place to learn about all kinds of music. My collection has a pretty extensive range of rock, blues, jazz, folk, country and everything in-between yet I'm completely ignorant about classical music.

B.K: The Canadian Music Hall of Fame awards are celebrating four distinct legends – Bobby Curtola, Andy Kim, Chilliwack and Cowboy Junkies. Where does this award fit in with the others on the mantlepiece?

We haven't been granted very many awards in our career, so the mantle is pretty bare. The awards we do have are generally kept in our studio and usually in the studio bathroom where one can take some time to reflect on, and properly appreciate the honours bestowed.

B.K: It was all about the club scene in Toronto. What clubs made it possible for the band to sort out its direction and what was it about the vibe and atmosphere that endures in memory?

When we were starting, there was a pretty healthy live music scene in Toronto. A lot of it centered around Queen Street, with venues like The Rivoli, The Beverley, The Horseshoe, The Cameron, Ultrasound, The Bamboo, and all of them were very open to new bands trying to get a foothold in the scene. The Rivoli was always very generous to us and later on we moved north to Clinton's on Bloor Street which kind of became our home. I remember those days as being very liberating, with audiences willing to go along with the musicians on whatever ride they took them on. The sheer quantity of venues and the willing audiences allowed bands to figure out and develop their “sound “ in real-time. It was a great way to develop chemistry as a band and playing live every week acted as a great accelerator.

B.K: When the band was ready to record you met Peter Moore and that now-famous high-end Calrec Ambisonic microphone at the wholesale price of $9000 he had purchased. Do you remember that first recording session and what you heard that was sheer magic?

Our first recording session with Peter was at our band house/rehearsal space on Crawford Street in Toronto. This eventually turned into our first album, Whites Off Earth Now!! What we loved about it was that it sounded exactly the way we thought we sounded when we got together in our rehearsal space and played. There was no attempt, and no way of hiding the rough edges, because it was a live stereo recording. When we went to do our second album, which ended up being The Trinity Session, we teamed up with Peter again because we wanted to keep the same what-you-play-is what-you-hear aesthetic. The combination with the natural atmosphere of the church was magical.

B.K: Kitchens and music were made for each other. How often did you sit around and sort things out and let the room have a say?

Allowing the room to have a say is probably the secret (or not so secret) of our success. The Ambisonic stereo recording of Trinity Session is all about playing to the room and allowing it in as a participant in the music.

B.K: Rejection is the measure of a band’s grit and determination. How did you handle rejection?

I think we've been pretty good about handling rejection and, for that matter, acceptance and praise. We have tried, over the years, to keep our focus on our music and accepted that everything else that swarms around it (various forms of rejection and acceptance) is about “the biz”. We try and keep the two worlds separate when it comes to measuring our success and failures.

B.K: The Trinity Session was in many ways a push back at technology – the first wave of drums machines and MIDI. Using two or three mic’s in a church and natural reverb – this must have sounded like heaven had welcomed you in?

Yes, it did. When we walked out of the church that evening we had the finished album in our hands, since this was a stereo recording with no mixing. When we listened to it the next day, we were a little stunned and overwhelmed by what we heard. We didn't know if anyone else would care or hear what we heard, but we knew we had accomplished something exceptional.

B.K: What was it about simplicity that gave the band a sound unlike that of the hits-driven artists surrounding you?

I think it was the first time in many years where, on a recording, you could hear musicians communicating with each other through their instruments. It's the most basic concept and the thing that makes pre-1967 recordings so exciting sounding and the thing that makes live music so vital. The advancement of studio technology was slowly leaching musical spontaneity out of recordings. The simplicity of Trinity Session made it sound so radical and original but, in truth, it was a very old school, conservative way of recording.

B.K: Once you became successful did you feel pressure from the majors to keep doing much the same?

No one knows what makes one thing successful. There are so many factors– timing, the music happening to fall on the right person’s desk at a convenient time. There are all sorts of criteria. To pretend you can replicate that on the next record - well, we have always thought that was a fool’s game. We just did what we wanted to do, made sure we were happy and the path we were following was a true one. We followed our gut even when there was external pressure.

B.K: Just recording in a different facility or circumstances will bring change.

We had a roots approach. The best way to capture the band was (live) off the floor. We still do lots of overdubs but as a producer I’ve always felt the energy of a band is best captured when they are playing live in the studio – at least for the bed tracks. The other side – where we record and how we do it – has always changed. That’s the evolutionary part of it.

B.K: Do you work with a core rhythm section on most projects or does that fluctuate?

It does fluctuate. There are players I use a lot. If I can bring them into a project I will, it’s nice to be with people you like and enjoy. It offers a high level of communication too.

B.K: How do you get new players who walk into your studio comfortable? Some younger players feel intimidated by the process?

I don’t know how I do it other than keeping things low key. The studio I have isn’t very intimidating. There’s no jelly beans in glass jars, no chrome, just lots of wood. I rarely do a project based on the clock, where you have to be out at a particular time or charging by the hour. There’s an understanding upfront that we are working together to make a great record and neither me or the band want something terrible to go out the door. I find people relax pretty quickly when there’s no pressure on them to produce. Recordings are easily erased. We can try again tomorrow - no big deal at all. The magic is in the playing and the actual session is what it is.

Are you a first, second, third-take guy?

Yes, that’s one of my jobs as a producer. I’m here to help guide the band through and let them know when it feels really good and point that out. I think I’m pretty good at doing that.

Trying to market music in a congested scene is difficult. How do you step around and get people to listen to all of this music?

These days there is a real choke-hold; that’s where things get stopped up. There’s lots of ways to get the music out there, but it can be tough to get people to listen. I haven’t figured that out yet. We try different things, all kinds of social media stuff. The old tried and true way is still the best, like getting the band on the road, getting them to play music. It’s hard for a young band to do that, most have other jobs. The key to success is to still have a good live performance and get out there and play.

B.K: Building a following is now a twenty-four hour a day grab for people’s social media attention. Do you think the band would have had the same impact in today’s climate?

Hard to say. I feel for any young musicians trying to get heard through all the noise these days.

B.K: Where there moments when you wanted to walk away?

In some ways we walked away around 2000 when we decided to not pursue another major label deal and instead decided to go back to releasing our music on our own Latent Recordings label.

B.K: What was the band’s big break?

It's hard to say if there was one “big break”. The re-release of Trinity Session internationally on RCA/BMG brought a series of breaks that allowed us to expand our reach around the globe. It was an exciting and perplexing time.

B.K: What concert remains the one you felt was that perfect moment – the one when everything roared beyond the expectation?

There isn't one specific concert that I can remember. Now and then you have a show where everything comes together and band and audience are in perfect synch. Musicians continue touring and killing themselves trying to recapture those perfect moments.

B.K: Are there recordings that stand above the rest in the deep catalog you return to and say this was us in our prime?

Not really. I think as a live band we are better now than we have ever been. Thirty years of playing together tends to do that.

B.K: Is there a place in the many travels the band was moved by the landscape and warmth of the people?

Brampton.

B.K: How often does the band get together socially?

That's a complicated question...three of us are siblings. But, as little as possible.

B.K: What’s up ahead?

More recording. More Touring. The actual road work gets wearing after a while and as you get older it’s harder from a physical standpoint – but playing live is still the best thing about everything. That’s what it’s all about!

B.K: What’s on the turntable?

It's waiting patiently for the release of Nick Cave's Ghosteen on vinyl.