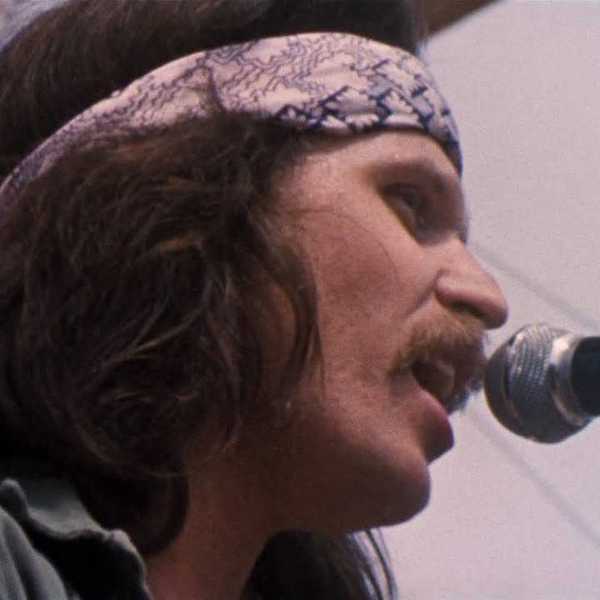

Canadian Music Hall of Fame Profile 2: Andy Kim

“I'm in town and I'm just putting together my 15th annual Andy Kim Christmas [on December 4 at Queen Elizabeth Theatre at Exhibition Place in Toronto]. I can't believe it's 15 years already.

By Bill King

“I'm in town and I'm just putting together my 15th annual Andy Kim Christmas [on December 4 at Queen Elizabeth Theatre at Exhibition Place in Toronto]. I can't believe it's 15 years already. It's a one-off every year. I feel like I'm starting over. I don't know if you were there last year, but last year it was mind-boggling. You get these dream teams.

We had Bif Naked, Mary Margaret O'Hara and then you get a surprise guest with Chris Hadfield. We had Alex Lifeson and Kim Mitchell. They both got together and played Battle Scar for the first time since the '70s. Tom Cochrane, Billy Talent, Broken Social Scene, Ron Sexsmith. I'm in the throes of that right now and I'm excited beyond anything to be part of this year's induction.”

I love Andy Kim. I love the hang, I love the conversations and the man. In-person conversations are eye to eye and brimming with enthusiasm - over the phone, electric. When asked to do this series on Canadian Music Hall of Fame inductees I thought about what I should and what I would ask each individual.

With Andy it had to be about the Brill Building in NYC. I’d visited a couple times and knew of its significance but in reality I would have been just as happy visiting the Village Vanguard where I caught jazz pianist Bill Evans playing Happy Hour. Andy lets go in this interview and takes us to a place we all have dreamed and walks us back to when a young man from Montreal hitches a ride to his dream and what a ride it’s been.

Bill King: How does the Canadian Music Hall of Fame differentiate from other awards?

Andy Kim: Well, you know what? I'll tell you something. It’s the iconic award, because it's all about the music. It's all about the songwriters. It's all about the artists that have had a dream that kind of broke through on radio and had a life outside of the life you would have had if your dream didn't kind of catch on. And to me, to be part of that tapestry of all those artists that came before me and even the artists that came after me, who got in before me. It's all incredible. People come to me and they say, oh, well, you know you should have been there, it's too late. Forget about it. What took them so long?

I come from another place. I turned to the person who said, it's about time. And I said, You know what? Here's how I've always lived my life as a kid and growing up in the tenements of Montreal. Somehow or other, I believed that I could to this. But I also felt something more significant, that God is always on time, not my time, not someone else's time, but his time. And I just figured, you know what? Thank you. Thank you, God, for this. At this time in my life, it's beautiful. It's just a total honour, as I'm sure everyone feels that, you know, hey, man, I'm lucky to be part of this playground because that's all I ever wanted.

We are living in times with politicians railing against immigrants. You're from a Lebanese family of immigrants. And anybody that immigrated here is susceptible to how times have changed and cling to their beginnings.

You know what I think, it’s the same for all of us. Even if your parents and grandparents were born here. That dream to become something is a universal vocation because my family came from the mountains of Lebanon and was completely blindsided by the fact that their third of four sons wanted to do this. And I can understand their anxiety because I didn't know if I had any talent. I just didn't know. I didn't know anything about the business. But I knew I saw this, and I think every kid, every kid at 10 or 11, 12 or 13 has some vision. They've been accepted at Juilliard so they could learn their craft. I learned my craft at the Brill Building. I was lucky enough to be around Gerry (Goffin) and Mike (Stoller) and Jeff (Barry) and Ellie (Greenwich) and Carole (King) and Jerry (Leiber).

B.K: How did you get past the front door?

First of all, we go back to the kid that I grew up with. The kid in me always was a great student. I loved going to school. I loved homework. I loved the whole aspect of learning. I would see music magazines in my two older brothers' room and I would always check the lyrics out. I would always check who is the songwriter for some reason or other. And my transistor radio would never really explain how it all works or what the essence of a record was. That inspiration I got from disc jockeys. You know what’s cool? Last week I spent like a good 40 minutes interviewed by Cousin Brucie (Morrow Sirius/XM). I don't know how many people remember Cousin Brucie, but he's iconic. And I remember listening to him on radio because my transistor would get WABC and WKPW in Buffalo - Joey Reynolds at night. And the way they talked about the artists and the way they talked about music, it just promoted this fantasy. So I would see Jeff Barry's name. Growing up, listening to the explosion of Be My Baby was like from another world. I never understood how those things got made but I'd always see Jeff Barry's name first. Jeff, Ellie and Phil (Spector), whatever Phil's participation was then he was there.

I think the fact that it was always Jeff and the fact that he and Ellie discovered other artists and produced Neil Diamond and all of that stuff. It was swirling around where you eventually think, you know that person. It’s like you've been watching a soap opera for many years and you finally bump into the actor or actress or I guess it's probably more polite or correct to say actor these days, and it's like, you know them, but you don't know them.

I knew the Brill Building and I didn’t have any map to get anywhere, but I knew the ballpark where I was going, and the great thing about GPS, I ask two questions: Where are you and where are you going? What's your destination? I knew both. I didn't know how to get there. You had to take a bus, get off on 42nd and Eighth, and then you walk and look at the names on the index and then you would see. What people don't remember or some people do if they lived it - when you walked into the Brill Building on the right, there was a Jack Dempsey restaurant. Dempsey would stand there and say hi to people as they walked into his restaurant. It was another time, another place. New York City is filled with people going everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

I went to the ninth floor and asked for Jeff and said I was in town for a little while and I have meetings at Columbia. I packaged a good story. And I still remember her name, Bonnie. She said, “I don't know because he's very busy” and I said, “well, can I wait?” I didn't know where else to go. What do they say? Ignorance and confidence will get you everywhere. And that was me. So I waited. And then she says, “he's got a couple of minutes and I’ll walk you into his office” and I sit down and he's on the phone. Five minutes go by, then ten minutes. I feel like maybe I'm in the wrong place because I don't know what Jeff Barry looks like. He finally gets off the phone and says, “So you've got a song to play me?” I say, “Yeah and I'm from Canada and my….. ”

He says, “So what's it like - the song that is?He loved the first two verses – “How Did We Ever Get This Way?” I got past the first two verses and the bah, lah, lahs and there'll be words here, and la la, la, la and words here. I didn’t know I was a songwriter. You have to understand that. I'm like cut and pasting what I think works. He listens, and says, “OK, you know, I'm running late, I gotta be in the studio. I love the first two verses the bah, lah lahs are the choruses but I don't like the third and fourth verse. So write them and get back to me.” I say to myself, Oh, my God. Okay. I don't know what to do. Barry looked at his watch again and says, “I’m late for the studio.” And I said, “can I ask you a quick question,” and he looked at me and I said, “you know, I've never been into a studio before. Can I come with you? I'll only stay a couple of minutes, I've never seen one before.” He looked at me and he said, “have you had lunch?” I said, “Yes," but I hadn't. He continues, “I usually get a sandwich and only eat half of it. I'll give you the other half.”

I have my guitar. I have a shirt and tie on and the jacket that was the uniform at the parochial school I attended. I'm now walking on Broadway with Jeff Barry. I'm eating the sandwich – he’s not talking to me, he's not even looking at me and we go into a hotel and downstairs into Mira Sound Studios. He waves to me to sit down on the couch, which I do. He enters the studio and I can't see him. Now, Jeff is like 6’ 4.” I’m like oh, my God. I'm here just a minute in a studio and it's Jeff Barry. There's a great saying that says you are what you eat. I think you are what you think all day long. I thought about this and not that I knew how it existed and how it unfolds.

I got up to leave and he waved me down. I stayed another two minutes and then I left and went to Bonnie to get all the information and phone numbers and everything. I was lucky that I had relatives in New Jersey. My parents worried, but they allowed me to do this. I then learned something that holds true today. I started writing three verses for every verse I wrote. And I finished How Did We Ever Get This Way and went into the studio with Chuck Rainey, Hugh McCracken and Buddy Saltzman and the engineer was Brooks Arthur, who went on to do Laura Nyro and Janis Ian. It was one of those moments to be brave and the mighty warriors will come to your aid.

B.K: I was in the Brill Building a couple of times – once with producer Paul Lekka with this band from Brooklyn I was playing with led by singer Vic Bonadona.

Not Green Tambourine?

B.K: How did you know that?

Oh my God, I remember meeting Paul Leka later on and him talking to me about, Green Tambourine and what he did in the whole thing, which was like really wild. I know he’s passed on now, but I always remembered. Maybe I'm just so interested and so excited about the dream that we all have.

We sat down, and he played a cassette tape of Green Tambourine. We looked at each other and I'm thinking, this is kind of like something I produced in the mid-60s’ when I arranged The Bells of Rhymney for the Chateaus - that Bob Dylan sort of thing. I'm thinking this is much the same thing and great for us. The track was already recorded. I think the studio band was the Trade Winds. Off we go with the track absent vocals and a gig out of town up in Maine. Leka keeps calling Vic – “I need you here now.” We were out for a month- just long enough for him to pull this group in from Cincinnati – The Lemon Pipers and they killed. I also remember after meeting with Paul and me, Victor, going down the elevator, there's Jackie Wilson in a yellow suit. Fuck me!

More about the Brill Building.

There's a book coming out on Jackie Wilson. Andrew Loog Oldham (Rolling Stones producer) has a friend in L.A. who's a writer, and at this moment his name escapes me, but he's writing a book on Jackie Wilson. We bumped into each other and he wanted to know about me seeing Jackie Wilson and Tina Turner. There was always someone iconic in that elevator only because, you know what it’s like? At that time, everything was iconic to me. Everybody was like they were there already. And for me to be able to, you know, take the elevator all the way up to to the ninth floor and eventually, have Jeff's office when he wasn't there. I could play and write stuff. At that point it became a walk-in room. I’m there and then Jeff would come later and then he’d say, “so what do you got? So what do you got? What do you got?” It became kind of a hook in my head. I’d keep writing. I've got to keep playing and you're only as good as your last two minutes and 30 seconds.

B.K: Sugar Sugar - How did you tailor this between the two of you?

First of all, Jeff became producer. He produced some of the Monkees stuff, in his relationship with Don Kirshner. I'm in Jeff's office and Kirshner had called, looking for songs. I think there was a cattle call probably, I don't know that for sure. Rumour had it Kirshner wanted me because he loved the sound of my voice on my records. He wanted me to be a part of the vocals for The Archies and stuff. I was Jeff's artist on his label. Not that he shot it down, but it was like, okay, but no. I'm in the office and I'm strumming my guitar and something comes out of my mouth that has no relation to anything. Ten minutes go by and the song is done. It's kind of the wildest, strangest thing in the world. Everybody will always hear me say, I never take a bow for inspiration. It was done.

I thought the percussion stuff was always the part of it that came easy. The hooks came easier for me than the verses. With all the hits I've ever had those hooks came out of nowhere. I was excited to be in a room with the iconic Jeff Barry, who's in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. That excitement opened up the barriers of being free just to say and sing what you want to sing, because there was never a bad idea. There was only an idea that didn't work. There's a better one here. There's a better way. Let's keep playing. I think playing the guitar - the rhythm and saying things out loud really helped. I don't know where it is now, but it's somewhere in Montreal- an incredible cassette player that Barry bought for me early on - How Did We Ever Get This Way time. I think I sounded like the greatest rhythm guitar player ever.

The condenser microphone made me sound incredible. And everything that we played - because when I'd be playing acoustic and singing and Jeff would be coming in there's like percussion stuff going on and he’d be banging on a filing cabinet and singing and coming up with stuff. It was a template for how well we worked together. And for me, I will never forget the fact that in the embryonic stage of my life there is a guy who took me under his wing. I became his co-writer. He was my mentor, but it became like we wrote songs together. I talk to him like at least a few times a month. And it's mind-boggling. I'm still that kid.

B.K: Rock Me Gently in 1974 became a number one charting record. When it hit the top of the charts, and you heard it play day and night on the radio, what went through your mind?

I put the record out myself because no one wanted to put it out. I wrote it and ended up having to produce it. When no one put it out, I came back home and called my mom. Everybody turned me down. It was like Andy Kim had had his run. Thank you see you. I remember I picked up the phone and called her and I said, “mom, I'm coming home.” She started crying because that's all she ever wanted was for me to come back home. But what she didn't hear was, I'm starting my new record company, my own record company. It's called ICE; long before beer companies and hip hop artists started using it.

I said I’m going to put out my record and I'm going to be my own promotion man. It's gonna be number one all over the world cause you're dreaming, right? As I look back, if you freeze-frame that conversation, you'll feel sorry for that guy. He went everywhere, not knowing what to do, then decided to put it all together because of the people that he loved and admired.

I’ve got to tell you one thing; there's a guy named Al Corey. He was the president of promotion for Capital. Do you know him at all? Well, you should look him up because the truth is when the Beatles broke up and they resigned and even when Lennon signed with Geffen, the first line in the contract, I may be exaggerating that point because I don't know what line it was, Al Corey did their promotion. Yes, the Beatles. Every one of them.

I got a phone call from Al Corey and he said, 'Andy Kim, you know you have a hit now in Detroit? I say, 'I hear and I have a truck driver that I'm talking to about bringing some units into the Detroit market because CKLW is playing it. He says, 'you need 20,000 records in the Detroit market by Monday.' This is a Wednesday. And I say, 'well, I don't know if I can do this. I can do it for you,' he says. 'I want to take your master over to Wally. I'm in L.A. at the time. This is Wally at Capitol Records mastering. He said, 'take your master over and I'll have 20,000 units in the Detroit market in no time. I say, 'do you want to speak to my attorney about a deal? I don't want to make a deal with you. I don't want you to lose this hit record. It's a number one record. It's one of the best records of the year,' he says. He continues, I don't want a memo from you, I don't want any deal. I want to save this record.'

Fuck, I had taken this song all over and over and over again everywhere and nobody wanted to put it out. I wanted to be on the charts again. I wanted to be in that playground and they were telling me, no. I went to Wally and I just let it go. It was bigger than me and it hit #88 with a bullet the following week on Billboard Magazine. Then the attorneys from Capitol and my attorneys made a licensing deal and all that kind of stuff. But at the end of the day, the issue is, what is your dream and how powerful is your dream that you will give everything up to follow that dream?I think it's so important there was a time when there was no auto-tune. Not everybody could make a record every day. There was no Facebook. There was no Twitter. There was nothing. You either had it or you didn't have it.

Rock Me Gently was on the charts for four months. I cried. Then a night I remember - Al Corey called me at midnight on a Tuesday, because Tuesday is when Billboard changed their charts. By the time you've got the print, it was the weekend. He told me it hit #1 on Billboard Hot 100. I cried like a baby. It was like an athlete or someone who just worked so hard to climb up that hill and, once they got there, not only are you exhausted, and you've given every ounce of your body and intellect and emotions into something, it really was so sweet. Then John Lennon gives me my gold record a couple of weeks later and I get to hang with him. So much that's been given to me was because I was brave enough to dream.