Major Music Streaming Companies Push Back Against Canadian Content Payments: Inside Canada's 'Streaming Tax' Battle

Spotify, Apple, Amazon and others are challenging the CRTC's mandated fee payments to Canadian content funds like FACTOR and the Indigenous Music Office, both in courts and in the court of public opinion. Here's what's at stake.

Some of the biggest streaming services in music are banding together to fight against a major piece of Canadian arts legislation – in court and in the court of public opinion.

Spotify, Apple, Amazon and others are taking action against the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC)’s 2024 decision that major foreign-owned streamers with Canadian revenues over $25 million will have to pay 5% of those revenues into Canadian content funds – what the streamers have termed a “Streaming Tax.”

Those funds will go towards established organizations like the non-profits FACTOR Canada and Musicaction, which financially support thousands of musicians and music companies across the country, and which have seen their own resources dramatically drop due to reduced contributions from private broadcasters. It will also go to funds supporting radio and local news.

The CRTC decision was one of the biggest Canadian music stories of last year, and legal challenges from those services, as well as the Motion Picture Association – Canada (which includes Netflix, Disney, Prime Video and the major U.S. producers and distributors of movies and TV), have pushed it into 2025. The courts have paused the payments until the appeal is heard by the Federal Court of Appeal in June of this year.

That pause has already put at least one fund under immediate duress. The Indigenous Music Office had been directed by the CRTC to launch an Indigenous Music Fund with resources from the streamers’ base contributions, but the delay impedes the IMO’s ability to start the new fund.

The conflict over the regulation is turning into a major struggle, one that illustrates the massive changes and challenges that Canadian music is facing in an increasingly digital landscape. It’s a modern wrinkle to a debate that has spanned decades in Canadian music and media.

“At the base of it, the streamers are questioning the validity of CanCon policies,” says Leela Gilday, musician and Board Chair of the Indigenous Music Office.

The Battle Over the “Streaming Tax”

The battle isn’t only happening in court, but in online petitions, political speeches and in Instagram posts from one of Canada’s most successful musicians.

“The Canadian government’s new music streaming tax is going to cost you more to listen to the music you love,” says Bryan Adams in a video shared on Instagram.

The “Summer of ‘69” singer, also a noted critic of Canadian Content regulations, has joined a lobby group called DIMA (the Digital Media Association) in publicly arguing against the regulation. DIMA, which represents Amazon, Apple, Spotify and YouTube, launched a campaign last fall titled “Scrap the Streaming Tax.” The campaign warns consumers that the mandated payments “could lead to higher prices for Canadians and fewer content choices” as a result of increased subscription fees.

Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has also publicly criticized the base contributions.

But many within the industry have welcomed the regulation, including the membership at CIMA, the Canadian Independent Music Association.

“The question for tech companies who are making money in Canada is: is it appropriate for them to contribute to the Canadian music ecosystem?” asks Andrew Cash, President of CIMA.

The answer from CIMA’s membership is a clear yes.

CIMA participated in the lengthy legislative and consultation process that led up to and followed the 2023 passing of the Online Streaming Act, which marked the first major update of Canada’s broadcasting regulation in a generation. Organizations like Spotify and Music Canada, which advocates for the major labels in Canada, also participated.

(Consultations related to other parts of the legislation continue, with implementation of the Online Streaming Act ongoing.)

“Canadians, through their democratic institutions, have made a decision about this,” Cash says. “And we can continue to debate it, for sure, continue to push back in the regulatory process which we are now in. But to come now with Bryan Adams in tow and try to dismantle the legislation, I don’t have much time for that kind of conversation.”

Is It Really a Tax?

Streaming services don’t need to be mandated to contribute to the Canadian music ecosystem, argues DIMA’s President and CEO Graham Davies. They already do.

“There is an apparent lack of desire to understand how music streaming services are currently investing into Canada,” he says. “For every dollar collected by the streaming services from the Canadian consumer, around 70% of that is paid through to the music industry to support Canadian music.”

That number includes payments to rightsholders, which Cash argues are the cost of doing business for streaming services, not a special support for Canadian music.

“That’s what you do to run your business,” he says.

Davies' reasoning reflects what Spotify argued to the Federal Court of Appeal as grounds for judicial review last July.

“The decision… is predicated on a misapprehension by the CRTC that Spotify, as an online undertaking, does not in any manner contribute to the creation and success of Canadian content,” the Application stated.

A subsequent filing argues that the definition of Canadian content is unclear. It also argues that the mandated fees qualify as a tax, not a levy, which the CRTC doesn’t have the legal authority to impose.

Cash, though, says calling this a tax is inaccurate and argues that the name of DIMA’s “Scrap The Streaming Tax” campaign is disingenuous. It’s not technically a tax at all, he says, since the money goes to independent content funds and not government coffers. The regulation also does not require streamers to raise their subscription fees – though at least one, Spotify, already has, following a fee increase in the U.S. last summer.

“It’s not really clear to the average Canadian that the biggest most powerful corporations in the history of capitalism are behind this campaign,” says Cash.

That’s not how Davies would characterize DIMA’s members’ operations. He says the streamers are already operating on a slim margin, and the mandated payments make those operations more difficult. “The pressure that they are being put under is something that the consumer needs to be aware of,” he says.

Streaming services are investing from their profit margin into on-the-ground teams in Canada that promote new Canadian music and support cultural events and activities in the country, he says.

That includes initiatives like Amazon Music Canada’s Breakthrough Artists to Watch program and partnership with the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame or Apple Music’s support of the Canadian Country Music Association’s Songwriters Unplugged Series. Spotify has had partnerships with Canadian festivals like Boots & Hearts and Montreal Jazz Fest and offers support to artists through masterclasses and other programs.

“We would absolutely say that the services’ current approach is really successful,” Davies adds. “What is the problem that is wanting to be fixed here?”

Why Canadian Content?

In certain ways, the debate goes back to the 1970s when CanCon regulations were first developed.

At a time when Canadian radio was dominated by American and British acts, broadcasters were mandated to devote a percentage of their airplay to music deemed Canadian. The massive size and influence of the United States just south of the border birthed a wider industry strategy of funds and grants to foster Canadian music and art.

Now that music is so dominated by digital platforms, Cash argues that the investments already made by streaming services are not enough on their own to build careers, let alone foster a whole industry.

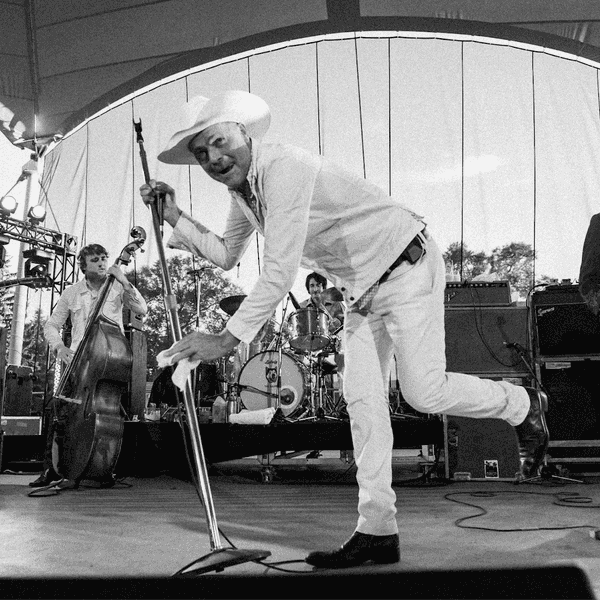

“Over the last five years, FACTOR has supported over 6,500 artists across the country,” he says. He points to artists like Charlotte Cardin and The Weeknd as just two musicians who received key early investment from FACTOR and now have thriving international music careers.

FACTOR CEO Meg Symsyk says the organization is adapting to rapid changes in the global music landscape, helping Canadian talent stay competitive while global companies enter the country’s marketplace.

“There are many recordings, wider marketing efforts and artists playing live in many more places to develop and grow their audiences that would not have happened without extra financial support from key sources such as FACTOR,” she writes.

Gilday, of the Indigenous Music Office (IMO), is excited about the idea of potentially working with streamers in directing the mandated payments.

The IMO has plans to launch a new Indigenous Music Fund in Canada, with 0.15% of the audio payments earmarked for its launch. This fund which would distribute finances directly to Indigenous creators. Another 0.35% of the funds are designated for “direct expenditures targeting the development of Canadian and Indigenous content.”

Those resources are an important step in the context of colonial policies that have suppressed Indigenous arts and culture throughout Canada’s history.

A new organization, the IMO is focused on building relationships with Indigenous musicians and music industry members across the country, with a governance model and mandate informed by traditional principles from nations like the Dene Laws, the Two-Rowed Wampum and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit.

While Gilday says she has seen the streamers show interest in investing in Indigenous music, organizations like the IMO have put the time and resources into community relationships and know best how to support Indigenous artists.

“Many of our people are still struggling with the legacy of colonial trauma. And so for an Indigenous artist to make steps towards creating or recording or releasing or touring their music, those steps are much more difficult than a non-Indigenous artist,” Gilday says.

Streaming Service or Radio Station?

“Radio and audio streaming are not the same,” wrote DIMA and Music Canada in an open letter this past fall to the CRTC.

Following a series of workshops on implementing the new legislation, the groups concluded that the CRTC was approaching streaming services too similarly to traditional broadcasters.

“The product and the business model that exists for music streaming is very different from radio,” says Davies.

Radio is curated by one to many, he points out, while streaming is oriented around listener selection.

“The services are making available millions of recordings and access to the world wide repertoire of music,” Davies says. “This is not a local, national radio station. These are global services.”

That means that artists on streaming services have a potentially larger and broader reach, as DIMA and Music Canada write in their letter.

“Three of the top 10 songs streamed in India in 2022 were by Canadian artists,” they state, “a fact that would be inconceivable to the founders of our terrestrial broadcasting system.”

Streaming services are certainly generating revenues for the Canadian music industry. But the distribution of those revenues is a thornier subject. Spotify has faced criticism in the last year for de-monetizing any songs under 1,000 plays, making it harder for emerging artists to get revenues from the platform.

Brian Fauteux, Associate Professor of Popular Music at the University of Alberta, tells Billboard Canada that the top three artists in the country – Drake, The Weeknd and Justin Bieber – occupy a bigger share of the pie than in previous eras.

A study co-authored by Fauteux found that in the ‘90s, the top three musicians controlled only 5-10% of the market share. In the 2010s, the top three reached as high as 46%.

The number of Canadian artists reaching the charts also seems to have shrunk: in the ‘90s, 306 distinct Canadian artists had songs in the Top 100 Singles Charts, compared to 246 in the 2010s (2009-2018).

A report by Music Canada last year revealed that roughly 10% of the most-streamed artists and songs in Canada are Canadian – and that includes artists beyond the big three, like Cardin, Josh Ross and Karan Aujla. Streaming can also allow artists to bypass the institutional white male bias of radio – like with the success of Punjabi Canadian music.

But streaming alone doesn’t provide the infrastructure necessary for a healthy music ecosystem – particularly one that exists on the American border, Cash notes.

“We need to confront that reality,” Cash says. “One of the ways we do that is by trying to find ways for the sector that’s benefitting [from it] to contribute to it.”

That’s become trickier as radio contributions have declined, with radio ad revenue dropping as advertisers flock to digital platforms.

“There’s history here of those sorts of media institutions paying into Canadian content development,” Fauteux says. “The point is more about putting measures in place that continue that legacy, as opposed to trying to regulate them just as radio.”

Opportunity for Collaboration

This isn’t a zero sum game.

If organizations like FACTOR and the IMO successfully invest in Canadian music, that should mean more revenues for streaming services, too.

But the payment pause makes it harder for those investments to go to plan. The IMO was scheduled to undertake a series of consultations with community members in 2025 to begin development of the Indigenous Music Fund, and now Gilday says they’re working to find alternate resources in order to fulfill their legal and community obligations.

As the case makes its way through the court system, Canadian and Indigenous music organizations will plan as best they can for the future – including for collaborations with the streaming services directly.

Gilday mentions SOCAN’s Indigenous Song Camp, which is supported by Amazon Music, as an example of the ways streamers have already shown their willingness to engage.

“I don’t see this as an adversarial situation,” she adds. “I think we can all work together towards our goal.”

FACTOR has previously provided funding to Billboard Canada and to the musical project associated with this article's author.

- Spotify Raising Prices in Canada While Challenging Proposed 'Streaming Tax' ›

- Canadian Court Pauses So-Called 'Streaming Tax' on Companies Like Spotify, Amazon and Apple ›

- Music Canada Files to Join Court Battle Over 'Streaming Tax' | Billboard Canada ›

- Music Canada demande à intervenir dans la bataille judiciaire autour de la « taxe sur le streaming » | Billboard Canada ›

- U.S. Congress Republicans Pressure Canadian Government to Suspend ‘Discriminatory’ Online Streaming Act | Billboard Canada ›

- Les républicains du Congrès américain pressent le gouvernement canadien de suspendre la loi sur la diffusion continue en ligne jugée « discriminatoire » | Billboard Canada ›

- Canadian Music Industry Weighs in on How to Support Canadian Audio Content at CRTC Public Hearings | Billboard Canada ›

- L’industrie musicale canadienne s’exprime sur le soutien au contenu audio national lors des audiences publiques du CRTC | Billboard Canada ›

- CRTC Removes Radio Licensing Terms, Instates New Administrative Changes to ‘Reduce Regulatory Burden’ | Billboard Canada ›

- Le CRTC supprime les dates d’expiration des licences radio pour « réduire le fardeau réglementaire » | Billboard Canada ›

- New National Report Calls for Boost to Indigenous Music 'Discoverability' in Canada’s Streaming Era | Billboard Canada ›

- Un nouveau rapport national appelle à renforcer la visibilité de la musique autochtone sur les plateformes d’écoute en continu au Canada | Billboard Canada ›