A Conversation with Leroy Emmanuel of LMT Connection

Since forming in 1989, the trio has crafted a distinct blend of R&B, funk and jazz, aptly termed “Universal Soul.”

LMT Connection

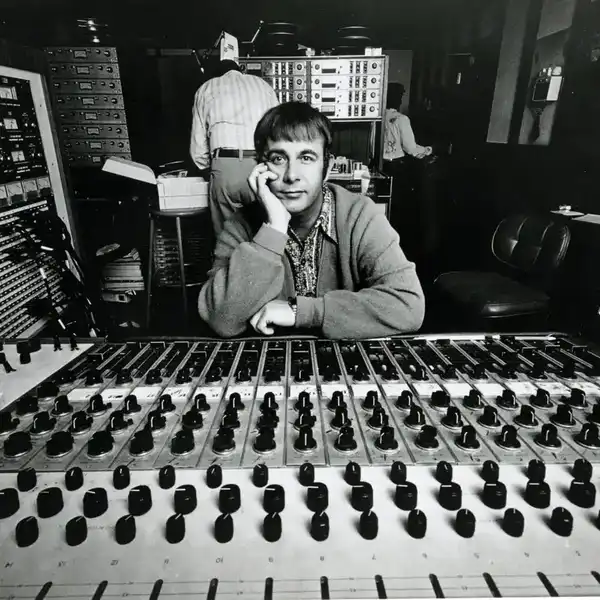

Leroy Emmanuel and LMT Connection recently played a riotous December Friday gig in Toronto. It was a chance to hear the band at the Redwood Theatre in the East End in peak funk form, in magnificent audio and in front of an appreciative audience. What strikes you about the trio is the fatness of the sound, tight and edgy. The centrepiece was 77-year-old Detroit native Leroy Emmanuel’s punching guitar, that cross between jazz and hard funk. It's not that Toronto jazz guitar resonance that alludes to the late Ed Bickert, a genius in his own right, but one that intersects with the likes of George Benson, John Scofield and Pat Metheny.

Emmanuel honed his style in the studios of Detroit during the ‘60s. His folks planted roots in 1953 as Billboard's Rhythm & Blues chart was plying the neighbourhoods with top 10 fare: Ruth Brown, “(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean,” Fay Adams, “Shake a Hand,” “Hound Dog” before Elvis snatched with Big Mama Thornton, The Orioles, “Crying in the Chapel,” The Clovers, “Good Lovin’.”

Throughout our conversation, Leroy speaks with authority. I get that. I’ve heard him play live and agree with his assuredness. There’s no stop and start. No looping and editing. Virtuosity lies at the heart. It's much the same with the two stellar players at his side.

In 1984, the roots of LMT Connection were planted as Mark Rogers, attending a club show in Niagara Falls, approached Leroy Emmanuel, the featured band’s guitarist. Their musical chemistry sparked, and a year later, Emmanuel returned to Niagara Falls, reuniting with Rogers. The duo embarked on a four-year journey across North America with a 10-piece Motown band. As the tour concluded in 1989, they welcomed Ottawa native bassist John Irvine into the mix, solidifying the trio that became LMT Connection.

Since their formation, LMT Connection has been a force in the music scene, crafting a distinct blend of R&B, funk, and jazz, aptly termed “Universal Soul.” With a musical journey spanning over four decades, the trio has recorded four studio albums, with their third, Universal Soul, released in the fall of 2003. Over the years, they’ve mesmerized audiences with over 6,400 live shows and embarked on six European tours in the past two years alone. Notably, they were honoured to open for the legendary B.B. King, marking another milestone in their illustrious career.

A few years back, I asked Orbit Room co-owner Tim Notter about LMT Connection, knowing the hot spot had a solid 25-year history before closing.

"I asked Prakash John. I told him I’m looking for bands that play soul music. He said I should check out LMT Connection who never play in Toronto because their entire world is Buffalo, Niagara, Niagara Falls area, Hamilton. I didn’t know they lived in Niagara Falls and were going to drive up from there.

"Of course, the first time we saw them, our jaws dropped. We were amazed by the three of them, thinking it was the most incredible thing we had ever witnessed. Leroy Emmanuel is an absolute bona fide real deal soul singer from Detroit and Mark is an amazing drummer. They said Wednesdays night [were] the only nights they could play because they had house gigs all over the place. Six months from the start, you couldn’t get in the place. Some people still insist, 'Tim, I only attended on Wednesdays for ten years.'

"People could go to a bar and see any band play 'Hotel California' not very well [or] come to the Orbit Room and see the LMT Connection and be part of this insane party."

In this Q&A, Emmanuel talks about their rich history from Detroit to Ontario.

Let’s go back in time. You likely arrived in Detroit, what, around 1953?

Leroy: Something like that.

In neighbourhoods like Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, the last years saw significant changes. Those were the home of the blues singers and the big bands.

That’s when I met everybody: Marvin Gaye, I met the Pips, Tammi Terrell, Stevie Wonder, everybody. Stevie was a little younger.

I started working with Bettye LaVette when I was about 15 and did some stuff with her. She recorded “My Man” and hit the charts. Then, in motion and running, the early years spent at Motown. Johnnie Mae Matthews, people from the Four Tops, oh man, just everybody in Motown. I ran into [them] growing up before they started getting big hit records.

Eddie Kirkland was there, the guitar player, who played with John Lee Hooker? Who did you study guitar with?

I played with John Lee, and I can’t remember who the keyboard player, or the drummer, was. I think Motown bassist James Jamerson did some gigs with us. Matter of fact, me, Jamerson, a guy named Spider Rice, we had a little trio doing some different gigs around town. I met him at a nightclub through Bettye LaVette. I was playing with her, and the union president of the musician’s federation, a guy named Jim Lewis, was her manager. We got in and out of many places because he was the union president. We didn’t have problems playing anywhere.

What was your guitar style based on? What were you listening to?

I never had a teacher. Many guys were running around, playing. I was at the barbershop getting a haircut when I was about 14 and the barber asked me, “what do you do, son?” I said, “well, I play music.” He said, “what do you play?” I said, “I play guitar.” He then asked me if you had ever heard of Wes Montgomery? I said, “no.” He had a little record shop in the back of his place. He sold me an album for five bucks. I took it home and listened to it. It blew my mind. I thought, what in the world is this? I grew up listening to that album, and then I started finding other albums by him. [When I was] 19, 20 years old, Wes came to town and played at Baker’s Keyboard Lounge and I went down and waited until he got there during the day for rehearsal. I met him and we sat and talked for a while. He’s from Indianapolis, Indiana. I told him I once lived in Indiana. I was around seven years old, something like that and I went to school there for a couple of years and then moved into the Michigan area. I met the guitarist, Kenny Burrell. Those are the guys I was into, Wes, then Kenny Burrell and George Benson. That was the style, guitarist that catches my ear.

When I was 17, I did this record with Timmy Shaw, “I’m Gonna Send You Back to Georgia,” and it hit the Billboard charts. He went to the Apollo Theatre, and I was the only guy who knew how to play the guitar part. I was only 17, so he took me with him. I met Dionne Warwick, Chuck Jackson, Ruby & The Romantics. I started working with Dionne Warwick. I did a few concerts with her. One in Detroit with the James Brown Orchestra. That’s how I grew up. Working with various artists on their way to the top.

It opened the door to Motown studios.

I was playing with Bettye LaVette, it was Phelps Lounge on the east side of Detroit, and the house band was the Funk Brothers. Earl Van Dyke, Jamerson, Uriel Jones, Robert White, Eddie Willis, those guys. It was kind of a shock to them hear me play. How could I play at such a young age? I’m playing hardcore blues. One thing led to another, and I ended up getting called to do some Motown sessions. I guess the guys put a good word in for me, or somebody did.

Do you remember what sessions they were?

Not exactly. I was doing session work for various small home studios like Golden World Records. I was all over the place. I was getting called to do all kinds of stuff. And then I put together the Fabulous Counts. And we put out our first record, “Jan Jan” and blew Detroit off the map. We became the number-one band in Michigan, gigging somewhere every week. They started this battle of the bands and had a lot of impressive bands all around, young guys. There was Mad Dog and the Pups, Leonard King and the Soul Messages, all kinds of bands. We did some battles and the Counts always destroyed everybody with venues filled with people. A couple of thousand people, and about five, six bands, come on and play about three or four songs each. The Counts come on, and we would always win.

I was in the newspaper all the time, Detroit News. They sponsored us. We did all the big gigs around Detroit.

Another deep local label was Fortune Records.

I did so many sessions, I can’t remember half of them. I’m familiar with that label. Detroit housed a studio named Magic City. Whenever Ike and Tina Turner came to Detroit, they would call me. We would do demos with Tina Turner. They would take whatever they like, whatever they had in Chicago or California, and go back into the studio and record the tunes they like. They would always come to Detroit. Ike always had something going on. Well, I was looking at the list of musicians now.

Detroit was home to Reverend C. L. Franklin, Aretha’s father, the big gospel presence. There’s the jazz thing with Elvin Jones, Tommy Flanagan, Burrell, Ron Carter, Betty Carter, Joe Henderson. The blues thing, Big Maceo Merriweather, was the biggest star I would imagine coming out of Detroit. Everybody from Bessie Smith to Ma Rainey played there.

I saw Miles Davis with John Coltrane. I would stand outside a jazz club and listen to them play. I didn’t know who they were. I was just a kid. But all I know about the music was fantastic. That’s how I grew up.

Bootsy Collins.

Bootsy is still a good friend of mine. His brother Catfish and I were very close. I talked to Catfish about two hours on the phone before he passed away. The following year, I went to the NAMM show in Anaheim, California. I ran into Bootsy. I ran into everybody. I’m going this January; I go every year. I hooked up with Bootsy and we talked. Catfish had told him I had called. I met Bootsy when he played with George Clinton.

They must have had an enormous influence on your sound, Parliament-Funkadelic.

I influenced their sound. Because the Counts destroyed those guys. We toured with them, with the Counts and Parliament Funkadelic across the United States, in what we call the “funk invasion.” We did most of California across the United States, and all the way back to Detroit. There were only two bands. We were both on Westbound Records. We were good friends.

The Counts were an extremely polished group. I was the leader of the band, and when I put the Counts together, I’d make them rehearse about six, seven hours a day, every day. No playing sports such as basketball or hockey. We didn’t allow any of that stuff. I said, if you want to play that stuff, I’ll throw you out of the band. I was something else.

But that’s the same way James Brown was.

Yeah, I was worse than James Brown. James Brown was my man. James Brown had things in order.

You played on Marvin Gaye records.

I did some recordings at Golden World with Marvin. We did the You’re The Man album. Hamilton Bohannon was on it, James Jamerson, some of the Funk Brothers. I did some rhythm guitar, some lead guitar. They put the album on hold, as it had too much political content. We did that album in ‘72, I believe. They didn’t release it until 2019.

Marvin was a genius. Me and him were friends. He told me I was a genius. That’s what he used to tell me, he said, “Leroy, you’re a genius, man.” I said, “I’m not a genius, Marvin.” We’d sit there and smoke a joint in the studio when all the musicians were in place, just sitting there in complete silence. Marvin and I would laugh and talk. I’m sitting at the piano with him and rolling joints.

You came to Canada when?

Growing up in Detroit, I was always back and forth, as a kid, to Windsor. I knew all about Canada. Upon leaving Detroit, my intention was to determinedly reside in Canada. I got permanent residence here in 1986. I had a visa to play at the Sheraton Foxhead with a ten-piece band, a show band, at the Foxhead Hotel here in Niagara Falls. I believe the district manager of all the Hilton hotels was from Texas. He was a hardcore guy and had people taking care of business. He ran the places around here like crazy and knew how to run his business. He didn’t like anybody in my band, the Power Play show band. The only guy he wanted in the band was me. His name was Ray Ferringer.

I stayed at the Sheraton when I played at the Penthouse six nights a week for the entire summer season. I would run into Ferringer in the lobby and say, “Well, good morning or good afternoon, Mr. Ferringer, how are you doing today?” I would speak to him. Most of the people working feared him. He was a big guy, a big Texan. But I’m from Georgia and worked in Texas. I worked all over the place. You know he didn’t phase me one way or another. After a few times of that, he stopped me one day. He said, “where have I seen you?” I said, “I play in the band upstairs with the Power Play.” He asked, “you stay here.” I said, “yes, I do.” And he said, “It’s a good band but I don’t like those guys.” He was straight ahead. They’re all from Toronto. They had the Toronto attitude. I had a few run-ins with Toronto musicians and had to straighten them out.

How did you end up playing Orbit Room in Toronto?

One night, Alex Lifeson from Rush showed up. He used to check whatever band was playing at the Orbit. He’d come in for maybe a set or 10 or 15 minutes, then gone. And one night when we started playing on Wednesday, he came up, sat down, and talked to co-owner Tim Notter and a few other people. Then the LMT Connection went on. I just started playing a little bit of jazz at first, just to kick the night off. I do that just to warm up. Then I took off on some stuff. I don’t know what I was playing. The place started rocking. I noticed he was there for the whole first set. Then for the second set. He was there until the night was over. Tim said Alex never stayed in the bar that long. He’d come in, check things out, and leave. He sat there all night until I came downstairs. I asked who that was. Tim said that’s Alex Lifeson. I said, “Alex Lifeson from the band Rush?”

I introduced myself. Lifeson stood up and shook my hand, looked at me and said, “Man, I ain’t never seen anybody play guitar like that. That’s the best.” He continued, “I don’t have a clue — how do you play guitar like that? You don’t use a pick. You’re all over the place — you know, and you’re singing — and you don’t miss a note. I know some great guitarists and some great singers, but guys that can do it seamlessly, it’s a handful, you know.” I’d sing something and run a harmony with myself on guitar, while sometimes singing on certain things. He said, “how the world do you do that?” I taught myself how to do it, and I’m self-taught. It comes naturally.

You and drummer Mark Rogers, what a team. I guess you first met in 1984 and formed LMT Connection in ’89. The first time I heard him, I went, where is this guy from? He’s a hard pocket player.

He was born in Oakville, but went to school in Chippewa in Niagara Falls. Basically, that’s his stomping ground. He grew up here.

I was playing in the Penthouse, and Mark was a kid just coming out of high school. He was running all over the place, checking out everybody playing. Somebody said, man, you got to go there and listen to this band — and this guy from Detroit, on guitar. They said you got to check that guy out. That guy is the funkiest guy I ever heard in my life. He knew people working in the show and came up one night while I was playing with the band. He walked up to me and said, “Wow, I play drums, man, I would love to play with you.” He was just a kid. He was like 18 years old. I said, I got to go back to Detroit, I got some concerts I got to do. I got to do some stuff with Marvin Gaye. He said, “what?” I said I got to do a concert in Atlanta at the Fox Theatre. And I was recording with Bohannon and Sheila E. was on some Funkadelics and Ray Parker Jr., Wah Wah Watson. Funk, disco, dance album. It was something else. It’s still out there. I said, I’ll be back in a year. I got some stuff I got to do in the states.

I came back the following year to Niagara Falls. I had Mark’s number. I promised, “I’ll call you when I come back”. He didn’t think I would. So, I called him. He was in a state of shock. He said, man, “I can’t believe it, man, you remember me?” I said, “yeah, I told you I would call you.”

We got together. I wanted to hear what he sounded like on the drums. I didn’t know what this kid sounds like. We started jamming. That’s when I first heard him play. He was kicking like others I played with in Detroit. Some bad dudes. I played with undoubtedly some of the best in the world, on drums. I taught Ricky Lawson. He ended up playing on the album with Michael Jackson, “Bad,” started touring with Michael Jackson. When Ricky Lawson was young, his uncle and I did a lot of producing together.

Then you got with bassist John Irvine.

I mean, then it’s complete. John came down from Pembroke. He was born somewhere in Ottawa and worked as a bartender. He was telling people, “I’m searching for a musical endeavour. I play bass.” A friend of mine said, “Man, I know the gu,y he’s teaching at the music store, go over and talk to him.” John came over and said, “I play bass.” Okay, man, let’s see what you got. He said, “I never played blues, I never played funk, I never played R&B, I played in progressive rock bands. I played with a group called Mindstorm and White Frost.” Some names I never heard of, but John could play that progressive rock stuff. He knew nothing about slap bass and none of that stuff.

I grew up playing with James Jamerson and the guys. I grew up playing with some of the best bass players in history. I’m sitting and listening to him. He played all this progressive rock stuff, and I like what he was doing ─ and I said, you heard of Stanley Clarke, Victor Wooten, and I named some names, he said no. I had some tapes, and I made him a tape of James Jamerson, Clarke and a few other names. I put it on a tape 90-minute cassette. That’s it. Study this. I said, these are bass players playing here. I said, listen to these guys. I said these guys are the best in the world. And he went like, oh? He sat and listened to that stuff day and night and started picking up on some stuff. I told Mark, I think we got a bass player, a guy named John Irvine. John felt apprehensive because he had never played funk in the pocket before. Then he started playing some crazy licks and some things I said play that again. He started playing and developing his own his style. Mark and John started getting together, and I wrote all these songs. The first album he did a fantastic job. John studied that stuff; it pulled it together.

It’s 35 years, 6,400 gigs later. You guys must be the hardest working band in Canada.

We don’t stop. We work two, three, four, or five gigs a week, year-round. That’s just out of Niagara Falls. That’s wild.

I bet many Toronto bands don’t even exist anymore because they hated us at first. Toronto bands hated LMT. We learned how to play music and be professional. I said, there’s no band in Canada that can stand up against us. I ask if you can find them, bring them on, and I’ll show them what being a real entertainer is about.

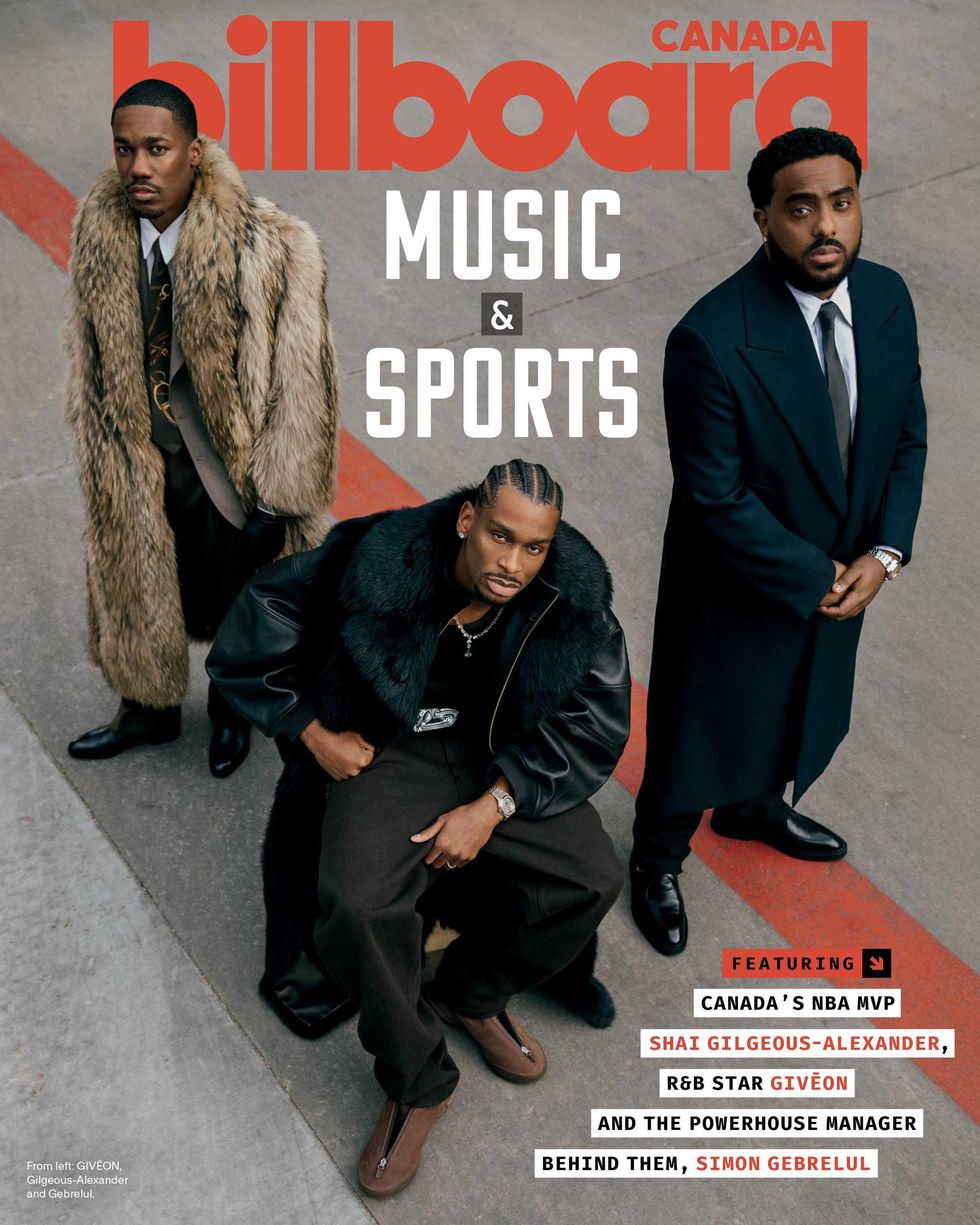

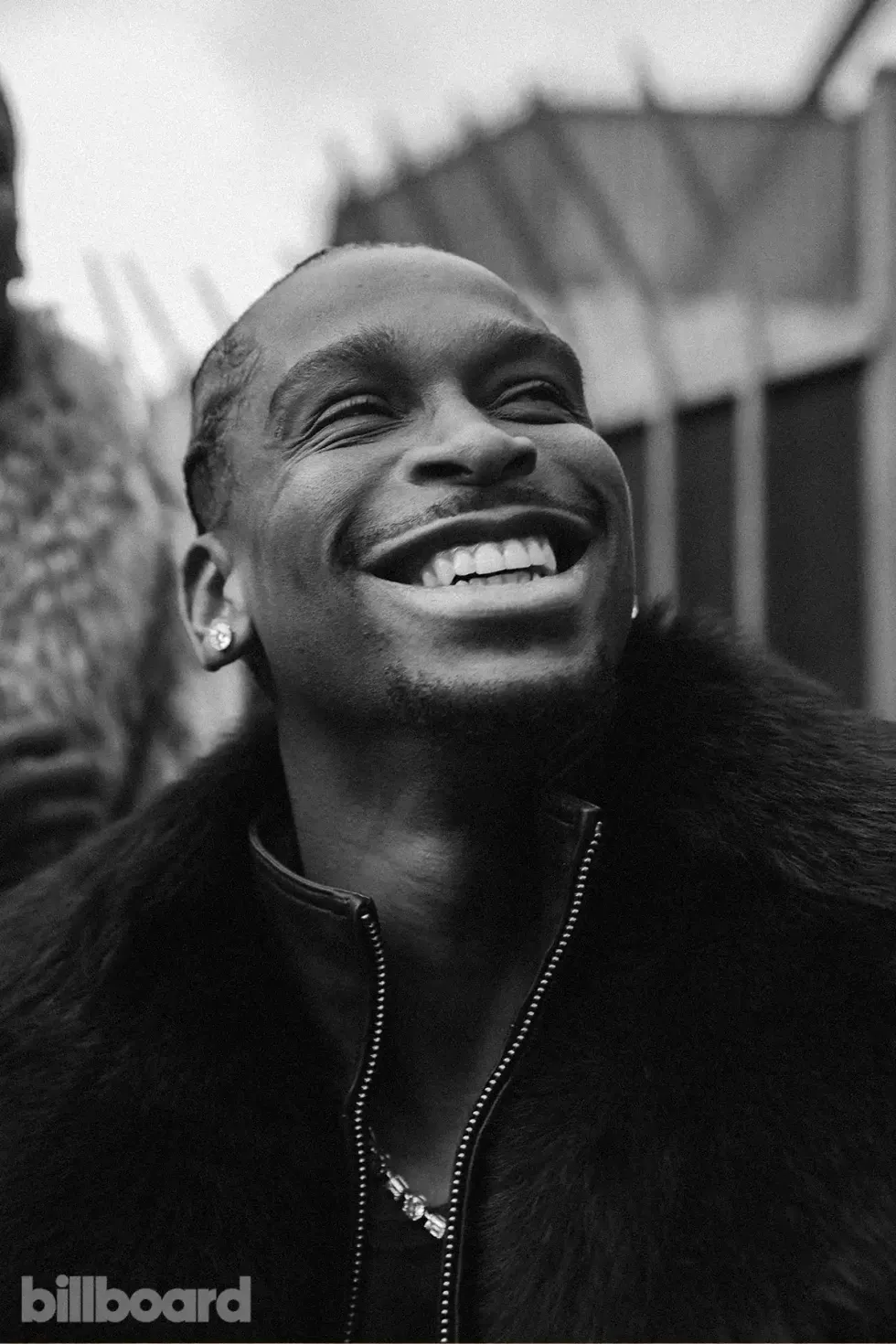

Simon GebrelulDiwang Valdez

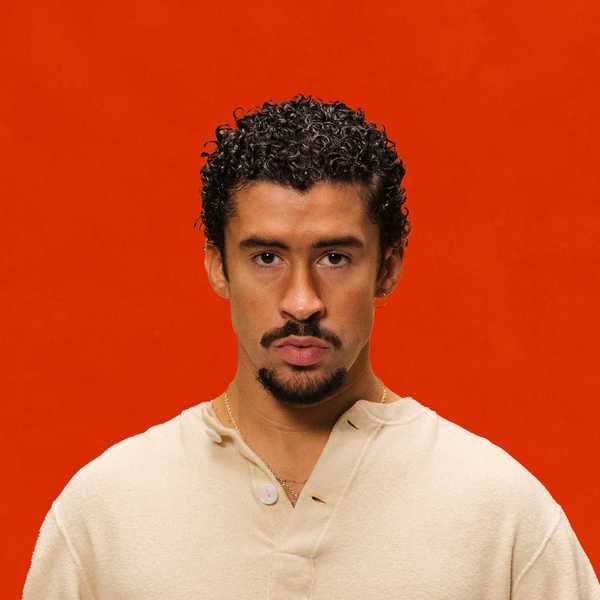

Simon GebrelulDiwang Valdez Shai Gilgeous-AlexanderDiwang Valdez

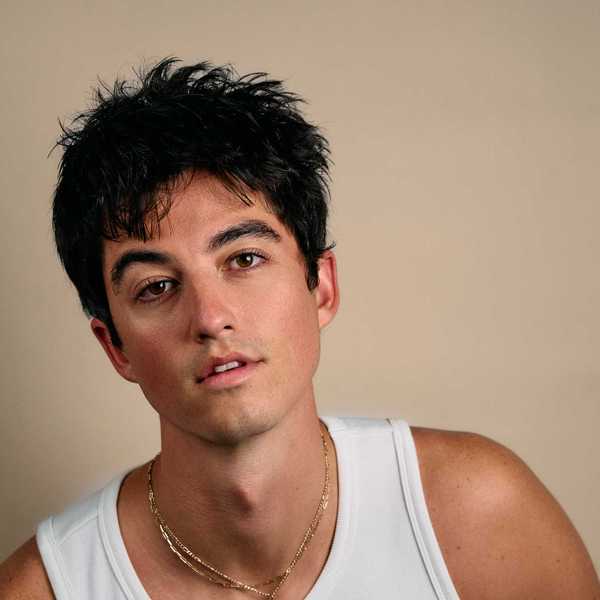

Shai Gilgeous-AlexanderDiwang Valdez GIVĒONDiwang Valdez

GIVĒONDiwang Valdez