A Musician’s Guide to Ed Bickert

Ed Bickert was born in rural Hochfeld, Manitoba, November 1932 and grew up in Vernon, British Columbia.

By Bill King

Ed Bickert was born in rural Hochfeld, Manitoba, November 1932 and grew up in Vernon, British Columbia. Mom and dad were both musicians – piano and fiddle players who performed at country dances off hours and when not engaged with family farming and orchard picking. Bickert’s first learned movements along the fretboard of the guitar came through his older brother who taught him basic chords. Ed would eventually join his parents on stage.

Bickert began his professional career as a radio engineer and at the age of 20 made a cross country move to Toronto. This was when week-long club bookings and frequent recording sessions became a natural part of Bickert’s musical evolution as he quickly earned “first-call” status and a regular member of reed player Moe Koffman’s quintet. It was also a time of cross border interaction as American jazz men toured Canada and would often spend a week or two in residence at one of Toronto’s prime jazz venues. Bickert was on or near the bandstand.

Ed recorded a dozen or so sides as bandleader and 50 as a sideman for key artists: Paul Desmond, Rosemary Clooney, Peter Appleyard, Moe Koffman, Rob McConnell – in fact, he was a charter member of McConnell’s Boss Brass. He toured or shared the stage with Oscar Peterson, Ruby Braff, Frank Rosolino, Milt Jackson, Buddy Tate, Ernestine Anderson, Benny Carter and the Concord Records All-Stars.

It was the passing of his wife Madeline in 2000 that sent Bickert into retreat. Madeline was at the centre of most all Bickert’s activities – fielding personal requests and scheduling dates. Not long after a hard fall on perilous ice and two broken arms - Bickert took a prolonged absence from the performance arena and out of the public’s eye. There were more questions than answers to his whereabouts. Several operations and encroaching arthritis compelled Bickert to leave the past in place and prized Telecaster in its case. No more public performances, no private tutoring, only the rare occasion when Ed would step into view as either a gracious bystander or supportive music fan.

Bickert had this to say in a Globe & Mail article six years ago; "I haven't played for 12 years, and I don't know if I could even remember how to hold the instrument right now," Bickert says with a laugh. "No, I just packed it up completely. Maybe I'd had enough … My wife passed away, and at the time, I was having some problems with arthritis, and I was starting to drink quite heavily, and those things combined sort of finished me off. I just never tried to get back to it. I envy or admire people who keep going until they drop. But it just wasn't for me."

His final days battling cancer were as much a reflection of the man’s understated persona and playing as his resolute character to the end. It was out of view and only known by a certain few. Bickert passed away recently at the age of 86.

I thought how wonderful and purposeful it would be to gather the thoughts and impressions of those closely associated with the extraordinary man. I’m indebted to those who shared with me their personal remembrances and the clarity of their words. A couple were posted on Facebook, and to those who said yes, we at FYI Music are truly grateful!

"A lot of the ideas I got for chords come from listening to bands. Well, Duke Ellington has always been one of my favourites, but there's a whole bunch of others over the years. Like Gil Evans, and people like that. They were making harmony much richer. And sometimes, we hear whole areas sounding dissonant for a nice change of colour."

Ed Bickert - Jazz Guitar Lessons

Bill King - The Radioland Jazz Session

The stage had been set and microphones strategically placed. This would be the setting for a significant undertaking between me and my Jazz Report Magazine/Radioland Records partner Greg Sutherland. From 1995 – 1997 we recorded three tributes to giants of jazz: Oscar Peterson, Wes Montgomery and Stan Getz. This began as a wish list and cause to bring together some of Canada’s finest jazz musicians to a specific project. In every sense, the projects succeeded beyond expectation.

The Wes Montgomery tribute – Portraits in Jazz in its own universe, is consequential. Over two sessions the east side of Canada was represented by six distinctive stylists: Peter Leitch, Reg Schwager, Rob Piltch, Ted Quinlan, Sonny Greenwich, and Ed Bickert. Each artist came with a rhythm section of their choosing; an original or standard with Wes in mind and a reinterpretation of a Montgomery classic.

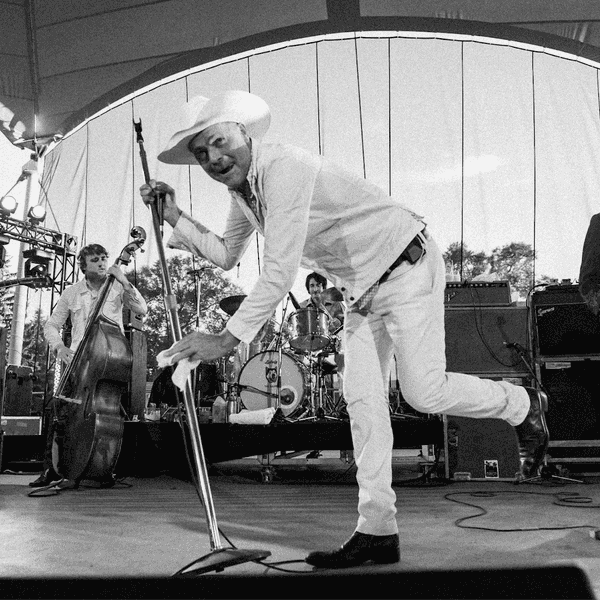

Every musician has a routine, and at times a peculiar set of rituals that play out before the audio engineer is set to press record. On this evening in 1996, Ed Bickert was “game on.” We worked 6-midnight – two songs in three-hour segments. Ed was slotted in the middle. With amp in place and his “living/breathing” Fender Telecaster perfectly situated on a chair next to him, we anticipated it would only be “punch the button and roll.”

Not the case!

Ed may have physically been in the room, but elsewhere in thought. A good portion of time passes when Ed returns to his seat, lifts the guitar and fiddles with the dials to his amp. While listening, we notice Ed’s sound growing darker and darker – more bass colouring and less treble – nothing that matched the previous players. Rather than interfere, Greg and I decided we’d leave all production fixes to mixdown sessions.

With rhythm section in place, two songs were chosen – “September Song” and Wes Montgomery’s “Twisted Blues,” we were ready to roll. Then comes the lighting of the Marlboro. Ed smoked the hard stuff – not those chemically enhanced menthol types or cigarette “lites.” Bickert gently places the Telecaster aside, steps in front of the wood paneling then raises the glorious pleasure stick to the lips, lights and drifts out of reach of the session at hand. Meanwhile, Greg and I begin to estimate the length of time this journey will require.

Both of us lose track.

Ed was now on “planet Ed”, and Greg was more than willing to enlist a search party to rescue. I cautioned and suggested we wait, knowing the recording will most likely be a “one take” situation. That it was! Ed eventually found his comfort zone and delivered two remarkable responses. To this day, I can’t help but marvel at the ingenuity in those tracks. The chordal patterns and sweet, sweet improvised patches are note-to-note perfection.

Before playback, we tinkered with Ed’s sound. Oh man, were we setting ourselves up for the “misplay of the century.” I asked the engineer “can we get a sound something closer to Pat Metheny”- and that he did. Ed arrives with Marlboro burning, listens, then nods his approval. Fuck me! He went for it. To this day, those two tracks are crystalline in their sound and utterly brilliant.

Don Thompson (bass/piano/vibraphonist/composer/educator)

The last time I saw Ed was a couple of years ago at Jazz.Fm91.1. He was interviewed, and Reg Schwager and I played. Ed seemed pretty good. He was in good spirits, and we had nice conversations, and then we left. My year was turned upside down and went right out the tubes for me, and I didn’t do anything that year. I lost track of everything and didn’t know there was anything wrong with Ed until Guido Basso told me a couple of days ago.

Ed and I go back to 1969 when I first came here. He was one of the first people I worked with, and we did everything we could do together for a long time. We played with everybody even before Bourbon Street started. We played with Moe Koffman’s band and did a record together in 1970, and I’m sure Terry Clarke was on it - Terry had just arrived here. Gary Binstead played bass, Terry drums and it was a beautiful record we did for the CBC. We did those records for Gene Perla and spent a lot of time together. That’s before we did the Garden Party record. The record for CBC was done as part of the transcription recordings and never sold in stores.

When I listen to those recordings now, I wish I played differently. I thought I knew what I was doing, but as I listen to them now, I wasn’t what I wished I could have been. I wish I knew then what I know now. I imagine it’s the same for most musicians. We played well together because Ed’s harmony was so logical and perfect. I never wondered about anything he did and knew exactly what it was, and it was perfection all the time.

Here’s what I always say about Ed.

I always considered him to be the George Shearing of the guitar because it was that smooth perfection in every chord. He never played anything that wasn’t beautiful, absolutely logical and perfect. When he reharmonized a tune he’d present to us, and you’d think, that’s the way it should have been written in the first place. It was different than anybody else too. It wasn’t that he was playing what Bill Evans played or anybody else; it was what he played. He kept coming up with new ways to play tunes you’d played a thousand times, and you’d think – this is better and what it should have been all along.

I don’t think he studied or anything like that. I think this is what he figured out on his own. It was just the way he could move the notes and the chords and the inside notes. It was amazing. Jim Hall, Barney Kessel or any of those guys didn’t play like him.

I was regularly playing with Lenny Breau, Ed Bickert and Sonny Greenwich. As far as I was concerned, they were the three greatest guitar players I’d ever heard. They all played completely differently. Lenny Breau musically was amazing but still when Lenny played it was about the guitar.

When Ed played, it was about the music. You never thought about the fact whether Ed Bickert had chops or not. It never occurred to you because it just didn’t matter. Lenny did all those amazing things on the guitar that nobody could do except him. Ed was perfect with the time thing, always relaxed. He could swing like mad, and there was never any tension or sense of urgency, much like George Shearing.

The Telecaster was his instrument, and I don’t think he could have done it on another guitar. It had a lot to do with that sound. It was so dark, giving the illusion the chords were way bigger than they were. It was that sustain, and he was so in tune that set him apart. He’d just tune up without asking for a note or anything. We’d tune to him. Lenny Breau and Ed were similar in that way. I’d ask Ed, “do you have a (tuning) note and he would say, I’ve just got what was leftover from last night.”

He has this great big Standel amp that weighed about a hundred pounds. During winters he’d leave it in the garage because it was so heavy. He’d get to the gig, plug in and it would take fifteen or twenty minutes before it would warm up enough to even work.

We did a really beautiful record with Buddy Tate and a guy that we knew came in with an amp and wanted Ed to try it out, and it was a nice amp but not exactly the same. Ed used it for the record date, but it wasn’t exactly the sound. Everything had to be perfect for Ed. The sound had to be perfect, and if anyone in the band was too loud it would drive him up the wall. I remember one night on the gig with Rob McConnell we were playing the Montreal Bistro – me and Ed and Rob, a trio gig and Rob counted off a tune and Ed was just sitting there. So, we stop, and this is on the stage, and Rob says, “what’s a matter, Ed?” Ed says, “too fast.”

We spent a lot of time driving to gigs and talked all the time. He also was really funny and sarcastic at times if somebody was being a nuisance. There was a trumpet player in the Boss Brass who used to warm up and play really, really loud and really high. It would be screeching and as loud as he could play. We were setting up for a television show, and the guy came in and it was kind of quiet and I’m taking the bag off my bass and suddenly we hear this screeching blast on the trumpet and Ed comes around me and says, “I guess you’ve got to let everybody know you’re here.”

Terry Clarke (drums/member of the order of Canada 2002)

I remember we did two weeks at Bourbon Street and the first week was so good. Don Thompson brought his trusty four-track down, and we recorded from Monday to Saturday three sets a night and let’s say four tunes a set – that’s twelve tunes a night times six – seventy-two tunes and never repeated a song. Frank Rosolino, Ed Bickert, Don and me. We had so much fun with Frank Rosolino - Ed chewed more gum and laughed more than I’d ever seen Ed laugh and he played two choruses and wiped us out. One chorus playing with Ed was intense enough. Rosolino would play fourteen choruses. He was the best damn trombone player. Him and J.J. Johnson and that’s it. John Norris put the recording on Sackville Records. It’s some of the best Ed Bickert out there.

We were playing with Moe Koffman and Mr. Ed was kind of languishing in a super sideman world and Don Thompson, and I went downtown to Bourbon Street one night and we had decided between the two of us we were going to make Ed the leader and we were going to be part of the Ed Bickert Trio.

We cornered him on a break and told him he was going to be the leader, and we would organize everything. The trio didn’t exist until we forced him to do it. That’s when we decided to record whenever we did and recorded live at George’s and a lot of CBC stuff too at Studio 4S. We somehow ended up with some Ed Bickert Trio records. He wasn’t going to get a band himself. Some of the recordings are from Don’s basement eight-track studio. I’m hearing things that have recently come out I don’t know quite where they are from.

Gene Perla put out PM Records, and those were CBC radio shows. We did a series of recordings later in the 70s’ and somehow Gene Perla got a hold of them and about to release on his label and CBC caught wind of it and busted him, so the only thing we had was a “live” thing at George’s Don had recorded we forgot about. Gene said he had it in his car and was listening non-stop. It was good but not as good as in the studio. He released a Doug Riley record and a Pat LaBarbara record from tapes he somehow got.

I knew nothing of Ed’s health issues until my wife Leslie saw on Facebook. I didn’t know he was at Bridgepoint – nobody told me anything. I think I saw a picture of Neil Swainson, Reg Schwager and Ed and it looked like he lost his hair. I think he must have gone through chemo. He sort of disappeared off the face of the map and I never spoke to him.

With Ed, it was always something in the process we never quite got to or played enough together. The Rosolino thing was the highpoint because Ed was having so much fun. If you just isolated the guitar solos he played, they were fantastic. The fact that Rosolino played with so much conviction, and we were having so much fun the whole thing got a little deeper.

The first time I played with Ed in 1970; we’d been watching Ed on television from Vancouver and everything that came down from Toronto that was jazz. The first time I got to play with him, I realized just the way he played made me cut out any bullshit that I was doing. If you played any bullshit, it stuck out like a sore thumb. It was a weird sort of thing. Without doing a thing he made me play what I was supposed to be playing. It was a very subtle message that anything you’d do that’s not going to be in context is going to stick out like a sore thumb more than it would normally. Ed made everything so clear you fell in line. You didn’t waste notes because he didn’t waste them.

My brother was a guitarist and tried to find the right guitar so he could get the Ed Bickert sound. We’re in Vancouver watching him on television, and my brother is a rock n’ roll guitar player and went out and got a Gibson ES 175, he got a Stratocaster, a Jazzmaster – he got every “master” guitar he could find and different amps to get the Ed Bickert sound. Flash forward 1969 and my brother moves to Toronto, he was a radio announcer and as soon as he gets here, he goes down to George’s Spaghetti House to finally get to see Ed Bickert live. He walks in and sees him playing that piece of shit Telecaster and that horrible amp and getting that damn sound he gets. Ken quit the guitar the next day. I think the amp had two little arms and it leaned back.

On the bandstand, if things weren’t going right, the left eyebrow would go up if you were flat and the right eyebrow if you were sharp. You know when Ed walked into a club everybody froze. You knew that the ears were here. The big ears. Rob wanted to know a certain chord we’d done, maybe in a Boss Brass recording and called up Mr. Ed and says, “Ed, you know in the bridge of this particular tune, you know the last part of the bridge, there’s some “grip” going on in there. Can you tell me what that “grip” was in this tune?” Ed says, “well Rob you know, in order to do that I’d have to get my guitar, and it’s down by the furnace in the basement and I’m not about to do that.”

Mark Miller (writer-journalist, critic, author, historian—and photographer)

It’s quite wonderful to see the respect and affection expressed on Facebook since news of his death. Few musicians on the Canadian jazz scene have been as influential, few as modest.

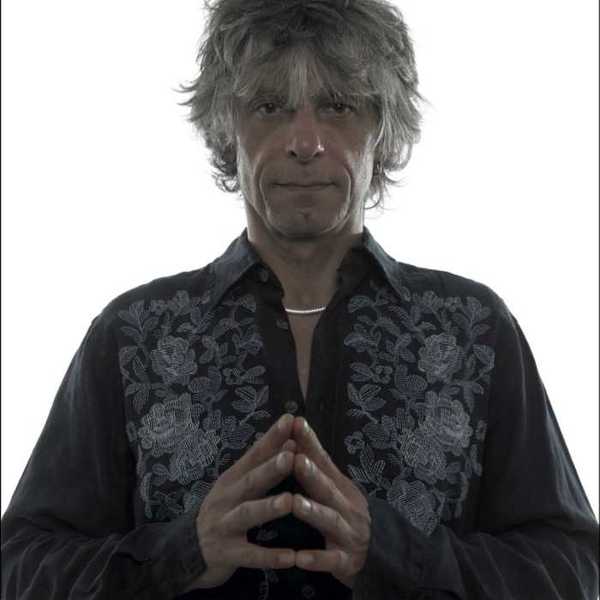

I wrote what follows back in the mid-1980s — around the time I took the accompanying photograph — and, with a little tweaking, it still seems to stand up.

His timing might have been a little better — generally it is impeccable — but Ed Bickert captured the essence of his own artistry one night late in 1981. The occasion was a Stéphane Grappelli concert. The place, Massey Hall.

Bickert and bassist Dave Young were opening the evening for the great French violinist. Pausing between tunes, Bickert started in on the usual introductions.

‘Can’t hear you,’ interrupted a voice from the hall.

‘Well,’ he replied, cooly and without apology, ‘you’ll just have to listen, because I don’t talk loud.’

It has probably been noted too many times before: Bickert’s is an artist of understatement. ‘He’s had to live with that word,’ observed a Toronto critic, ‘the way Raquel Welch has had to live with the stares of men.’

Not that it is inaccurate — this, after all, is a musician who would, in an already quiet set by the vibraphonist Red Norvo, take the ballad Emily as his own feature and make it the quietest piece of all.

No, ‘understatement’ is merely incomplete. It reduces to a single quality — a single attitude, really — a complex, personal approach to jazz.

It does not accommodate the kind of vivid harmonic colour that Bickert finds in the traditionally limited palette of the guitar — the kind of chordal extensions that, by judicious selection and elimination, he creates with just three or four notes and that, given a gentle pull, take on a soft, pulsing glow.

It does not accommodate the supremely melodic qualities of his solos; their harmonic sophistication notwithstanding, their direction is essentially linear — or rather, naturally linear, full of graceful movement and bluesy inflection.

Nor does it accommodate his sensitivity to changing situations. It is a different Ed Bickert who swings freely behind Milt Jackson than the one who nudges Red Norvo along, a gentler spirit who accompanied the late Paul Desmond than the one who pushes Rick Wilkins.

Ultimately, it may speak only to the fact that all of these qualities together form a dynamic of their own, one that — subtle though it may be — needs no further emphasis. Far be it for Bickert to add what is unnecessary. Still talking softly, now in conversation and ever in character, he backs into the admission that, yes, he has what has become ‘a recognizable way of playing… a style, I suppose you could call it.’”

Ted Quinlan (Head of the Guitar Department at Humber College)

“It’s impossible to overstate what a towering figure Ed Bickert has been in the Canadian jazz world and beyond. Years after his retirement from playing he has remained a constant source of inspiration as well as a favourite topic of conversation among musicians. The stories of his dry wit are legendary and point to the incredible economy, precision and boundless creativity of his playing.

I remember how flabbergasted I was the first time I heard him on Pure Desmond! I went to hear him play as often as I could and always marveled at the way he could spontaneously rewrite a tune, complete with the most sophisticated and beautiful harmonic accompaniment imaginable. His playing was free of clichés and fiercely improvisational while always retaining the common touch. The blues ran deeply in everything he played, and he set a standard for musicianship that not many people achieve.

I had an opportunity to be on a recording session with Ed where he had to overdub a solo on a particularly tricky set of changes. I had a look at the chords and imagined what I might do with them which probably involved connecting a series of lines and patterns that might fit with the harmony. Ed went into the studio and in one take played a perfect, simple and beautiful melody that made complete sense out of the accompaniment. I was totally blown away and told him how great I thought his solo sounded. Ed replied, “Some people seem to have good luck with recording, but I never have.” I thought of all the sublime solos I’d heard him take on recordings and live and realized then that his own standard, which already seemed unattainable, was even higher than I had imagined!

We’ve all been so fortunate in having an artist and a gentleman of this magnitude in our midst. Thanks, Ed, for your beautiful music and my deepest condolences to the Bickert family.”

Pat Collins (bassist, performer, clinician and educator)

I've been trying all weekend to think of something appropriate to write as a tribute to Ed Bickert but am struggling to come up with anything that is worthy. Ed was, without a doubt, the greatest musician I have ever played with. Ed taught me what's important about music, and my biggest takeaway from playing with him many times over the years is accountability. Whenever you played with Ed, you always felt that you couldn't "get away" with things, and really had to play something that mattered. This of course, is something that should always be considered, but with Ed it felt different.

Ed had the ability to bring out the best in your playing. Things never felt forced, but inevitably you'd play something that you knew you'd never played before, because of something he played.

I was lucky enough to start playing with Ed soon after I moved to Toronto. One of my fondest memories was playing for quite a few years at the Elora Mill Inn, west of Toronto. Rick Wilkins was also on the gig, and I certainly felt like I had died and gone to heaven. Both Ed and Rick never talked down to me, although they certainly could have, given my age and lack of experience. It was some of the finest playing I have ever been a part of.

Ed and I played together many times at the Mezetta Cafe in Toronto. Typically, Ed would have scribbled some tune titles down before he left the house and we would briefly discuss what we going to play that particular set. Often times at the end of his lists, he would write, "SOS". I let this go a couple of times, but finally got up the nerve to admit that I didn't know the tune, "SOS" and asked who recorded it. Ed just laughed and said, "That just means same old shit!"

Ed's musicianship, generosity and humour will never be forgotten by me, or by anyone else who knew, or played with him. I am a better musician today because of him. Thank you Ed.

Listen to Ed and various other guitar masters pay tribute to Wes Montgomery on Spotify and watch the tribute on YouTube below.

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey  Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey