advertisement

Billboard is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2023 Billboard Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

advertisement

Latest News

advertisement

BILLBOARD CANADA FYI

A weekly briefing on what matters in the music industry

By signing up you agree to Billboard Canada’s privacy policy.

advertisement

advertisement

Concerts

Kingston, Ontario's RoadTrip Music Festival Launches in September 2026

Polaris Music Prize founder Steve Jordan has teamed with Wolfe Island Music Festival co-founder Virginia Clark and the Kingston Downtown BIA to present the event featuring Peach Pit, Kasador, Katie Tupper, Mariel Buckley and more.

7h

Are you ready for a Road Trip?

RoadTrip Music Festival is heading to downtown Kingston on Sept. 12, presenting an all-Canadian lineup of musically diverse artists.

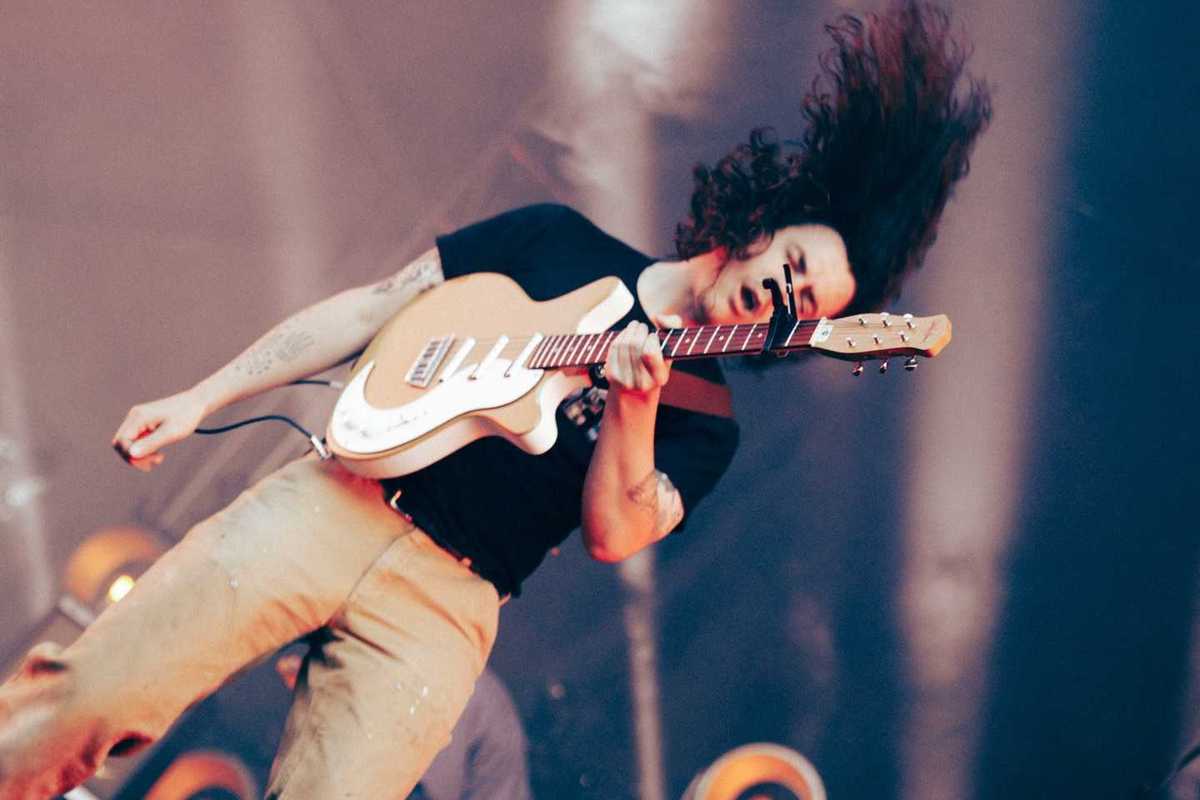

Heading the bill are Vancouver indie-pop favourites Peach Pit, Kingston alt-rockers Kasador, soul-pop artist Katie Tupper and alt-country songwriter Mariel Buckley, alongside Toronto dream-pop outfit Absolute Treat, singer-songwriter Gabriel Jacoby and hometown acts Tiny Horse, Piner, and O Green, performing on four different stages in the city's downtown core.

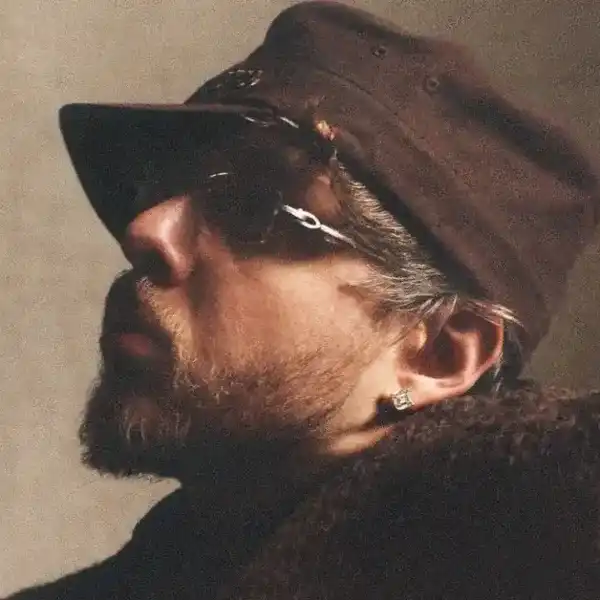

The event may be new, but one of the key players behind its launch is a very prominent Canadian music industry veteran, Steve Jordan. He is known as the founder and executive director of the Polaris Music Prize, a role he assumed for 15 years, prior to leaving to become the senior director of CBC Music in 2020.

advertisement

In a post on his LinkedIn a week ago, Jordan reported that "My longtime friend Virginia Clark and I have been working with the Kingston Downtown BIA on a new music festival, and it's called RoadTrip Music Festival. The name implies the activity, so fasten your seatbelts."

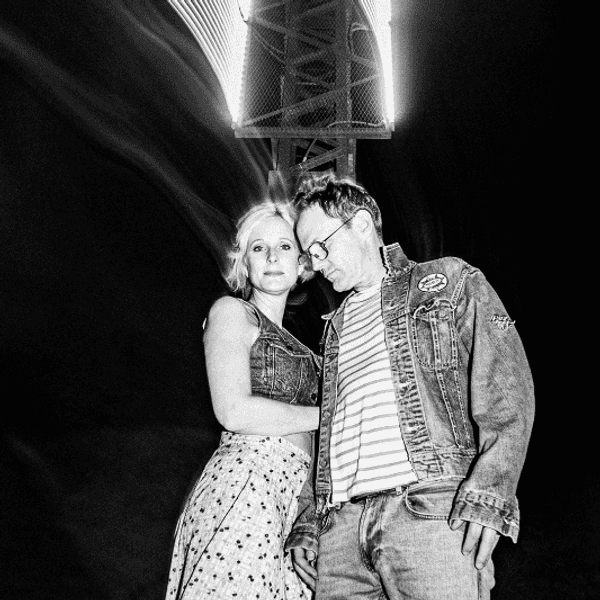

Jordan has teamed with Wolfe Island Music Festival co-founder Virginia Clark of Flying V Productions and the Kingston Downtown Business Improvement Area

"We’ve invited artists we deeply believe are exceptional," says Clark. "RoadTrip is about welcoming people to Kingston to spend the day with us — to walk our streets, discover new music, and celebrate together. It’s incredibly meaningful to create something like this in my hometown.'"

RoadTrip will feature daytime performances along Princess Street prior to main stage action in the evening. Check out the full schedule here. Tickets go on sale here on March 19 at 10 am ET>

Jordan's involvement with the festival represents a return to his hometown roots. He got his start in the business at Kingston radio station, CKLC, as a teenaged intern and eventually became music director before moving to Toronto and working in promotion for indie label Kinetic Records. He joined Warner Music Canada’s A&R department for a three year stint, prior to being hired as a talent scout for True North Records in 2002. He then devoted his energies to the Polaris Music Prize, one he launched in 2006.

advertisement

After joining CBC Music in March 2020, Jordan exited two years later. Broadcast Dialogue reported that "During Jordan’s tenure, he brought shows like The Block, Frequencies, Canada Listens, The Intro, and About Time to life, while parting ways with long-running programs, including Randy Bachman’s Vinyl Tap."

Based on the name of the festival, it sounds like the city hopes to show itself off to people driving in for the festival from nearby areas. Kingston has a rich musical heritage, most notably the hometown of Canadian rock heroes The Tragically Hip.

keep reading

Show less

advertisement

Popular

advertisement

Published by ARTSHOUSE MEDIA GROUP (AMG) under license from Billboard Media, LLC, a subsidiary of Penske Media Corporation.

advertisement