RIP: Rock 'n Roll Pioneer Little Richard

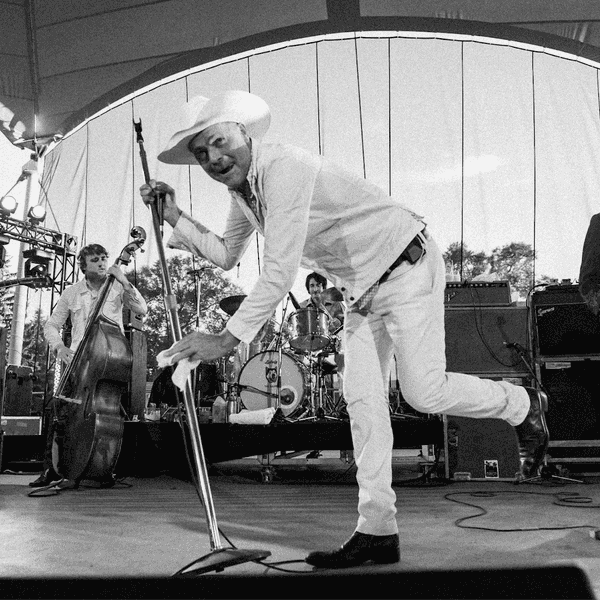

Between 1956 and 1958, Little Richard delivered a series of hits that helped establish rock ‘n roll as a vital new force.

By FYI Staff

Little Richard (born Richard Wayne Penniman), considered a founding father of rock ‘n roll, passed away on May 9, at age 87. His death, reportedly of cancer, was confirmed by his son, Danny Penniman.

Between 1956 and 1958, Little Richard delivered a series of hits that helped establish rock ‘n roll as a vital new force. Beginning with Tutti Frutti in 1956, he continued with Long Tall Sally, Rip It Up, Lucille, and Good Golly Miss Molly, all songs fuelled by his high-energy piano playing and signature vocal exclamations.

He never hit the top 10 again after 1958, but these songs and his flamboyant performing style would have a huge impact upon artists ranging from the Beatles and Elton John to Prince.

“I heard Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, and that was it,” Elton John told Rolling Stone in 1973. “I didn’t ever want to be anything else. I’m more of a Little Richard stylist than a Jerry Lee Lewis, I think."

The Beatles recorded several of his songs, including Long Tall Sally, while other artists covering his songs included the Everly Brothers, the Kinks, and Creedence Clearwater Revival to Elvis Costello and the Scorpions.

Little Richard was born in Macon, Georgia, one of 12 children, and he grew up around uncles who were preachers. Although he sang in a nearby church, his music didn't impress his bootlegger father Bud, who also accused him of being gay, resulting in Penniman leaving home at 13 and moving in with a white family in Macon.

After performing at the Tick Tock Club in Macon and winning a local talent show, Penniman landed his first record deal, with RCA, in 1951. He adopted the stage name of Little Richard shortly after.

The early singles he cut for RCA and other labels didn’t chart. His big break came when, while working as a dishwasher in Macon, he wrote Tutti Frutti and sent a rough version to Specialty Records in Chicago. He came up with the song’s famed chorus — “a wop bob alu bob a wop bam boom” — while bored washing dishes (he also wrote Long Tall Sally and Good Golly Miss Molly while working that same job).

In September 1955, Little Richard cut a lyrically cleaned-up version of Tutti Frutti which became his first hit, peaking at 17 on the pop chart. “Tutti Frutti really started the races being together,” he told Rolling Stone in 1990. “From the git-go, my music was accepted by whites.” Its follow-up, Long Tall Sally, hit Number Six, becoming the highest-placing hit of his career.

Little Richard’s sound fused boogie, gospel, jump blues, and rock ‘n roll, and it quickly propelled him to the popularity level of peers and fellow pioneers Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis.

As with Presley and Lewis, Little Richard also was cast in early rock and roll movies like Don’t Knock the Rock (1956) and The Girl Can’t Help It (1957).

But then the hits stopped, by his own choice. After what he interpreted as signs – including a dream about the end of the world and his own damnation – Little Richard gave up music in 1957 and began attending the Alabama Bible school Oakwood College, where he was eventually ordained a minister. When he finally cut another album, in 1959, the result was a gospel set called God Is Real.

Little Richard returned to secular rock in 1962. Although none of the albums and singles he cut over the next decade for a variety of labels sold well, he was welcomed back by a new generation of rockers like the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan and was especially popular in England, Germany and France.

When Little Richard played the Star-Club in Hamburg in 1964, the opening act was none other than the Beatles. “We used to stand backstage and watch Little Richard play,” John Lennon said later. “He used to read from the Bible backstage and just to hear him talk we’d sit around and listen. I still love him and he’s one of the greatest.”

He went on to tour relentlessly in the United States, with a band that at one time included Jimi Hendrix on guitar. By the end of the 1960s, sold-out performances in Las Vegas and triumphant appearances at rock festivals in Atlantic City and Toronto were sending a clear message: Little Richard was back to stay, though that would not last.

He was popular on the rock oldies circuit, as showcased by his sizzling performance in the 1973 documentary Let the Good Times Roll. During this time, he became addicted to cocaine while also returning to his gospel roots.

Little Richard's mystique or legend remained in the following decades. In the 1980s, he appeared in movies like Down and Out in Beverly Hills and in TV shows like Full House and Miami Vice.

His last known recording was in 2010 when he cut a song for a tribute album to gospel singer Dottie Rambo.

In the years before his death, Little Richard, who was by then based in Los Angeles, still performed periodically. Thanks to hip replacement surgery in 2009, he could only perform sitting down at his piano.

He retired after suffering a heart attack during a fundraising event in 2013 and was said to have spent much of his final days in a penthouse suite at the Hilton hotel in downtown Nashville, according to the Oxford American.

Speculation on his sexuality often followed Little Richard. He never publicly announced he was out, and in a 1984 biography, The Life and Times of Little Richard, written with his cooperation, he denounced homosexuality as “contagious … It’s not something you’re born with.” In 1995, he told Penthouse that he had been “gay all my life," then later claimed to be attracted to both men and women.

As a minister, Richard officiated at weddings for Bruce Springsteen, Demi Moore, Bruce Willis, Cyndi Lauper and other celebrities.

By the time he stopped performing, Little Richard was in both the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (he was inducted in the Hall’s first year, 1986) and the Songwriters Hall of Fame and was the recipient of lifetime achievement awards from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (in 1993) and the Rhythm and Blues Foundation. Tutti Frutti was added to the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry in 2010.

Sources: Rolling Stone, Ultimate Classic Rock, New York Times, Reuters

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey  Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey