Ralph Murphy: The Songwriter Who Became An Ambassador Of Songs

Now in his '70s, he remains optimistic about life — and about music. “The industry will survive,” he insists. “Music is still on the street — it’s still a vehicle for poor kids to get heard and get ahead, the same as it always was.”

By Richard Flohil

Years ago — well, if you insist, in the late ‘80s, when I worked for CAPAC, one of the two organizations that eventually merged to become SOCAN — I would always recommend that songwriters who were seeking advice and practical help should get in touch with Ralph Murphy. Thirty years later, I still do. “Take him a six-pack of Heineken,” I’d tell them, and one or two actually did.

Generous with his time and his knowledge, Murphy is a Canadian lighthouse on Nashville’s Music Row, offering a welcoming beacon of encouragement and support.

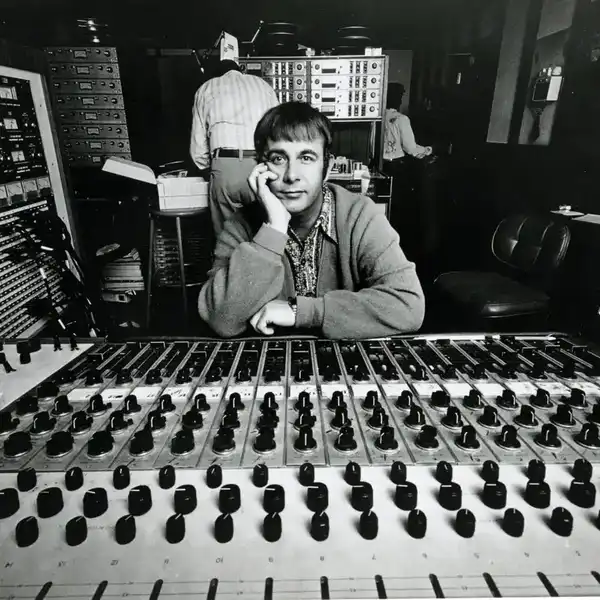

Born in Britain, schooled in Canada, Murphy moved to New York in 1969, moving to Nashville eight years later, and later to a prestigious job with ASCAP — Vice-President of International Membership.

He always retained his links with Canada, and, with old friend Randy Bachman making the presentation, he was recently given SOCAN’s Special Achievement Award.

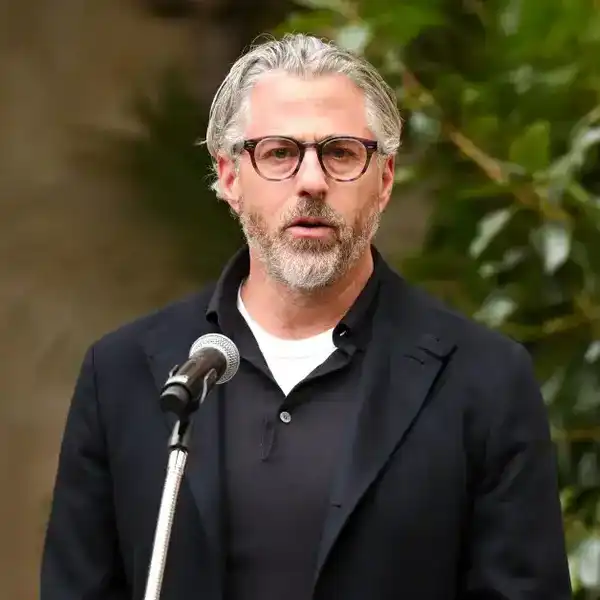

Now 75 and recovering from a bout of prostate cancer, he’s a familiar figure at every major music industry event in Canada — his lanky figure and white hair are visible at Canadian Music Week, the Junos, the Canadian Country Music Association awards, SOCAN events, and regional conferences and awards from one side of Canada to the other. Coming up: A trip to Dublin with ASCAP president Paul Williams.

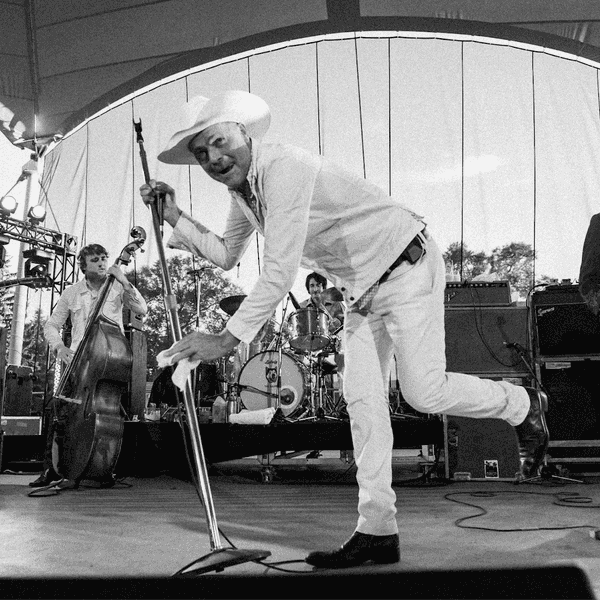

Tracing Murphy’s long career — now in its sixth decade — reveals a story of constant movement. He emigrated to Canada with his parents when he was six, and by the time he was 14 he was playing gigs in his hometown of Wallaceburg and starting to write songs. “I was floored by the Beatles,” he recalls now — and, working as a cook on a lake steamer for a summer to raise the money, he and a mate formed a duo and landed in Liverpool where they played in local clubs.

Finally discovering that the northern city was actually not “where it was at,” they got a lift down to London in a van with the road crew of a well-known band, who dropped them off at 5 a.m. in a snowstorm in Trafalgar Square. As Ralph tells the story: “My mate was so happy. ‘We’ve made it,’ he shouted in the early morning cold. ‘You’re an asshole,’ was my response.”

In a sense, they had made it. The duo got a record deal and a publishing deal with Mills Music; he moved in and out of a variety of bands, and — using his stage name James Royal—had his first hit at 19 years old. By the mid-60s was producing records for a variety of labels, and as the decade drew to a close, he moved to New York, in part to be closer to his family in Ontario — and was soon producing records for a variety of Canadian bands, April Wine, Brutus and Mashmakhan among them.

The songwriting never stopped — and his introduction to Nashville came after he had a #2 hit with Jeannie C. Riley called “Good Enough to be Your Wife.” “I liked Nashville when I started to visit. It seemed more open, you could walk everywhere, it seemed more friendly, and the weather was better.”

Permanently moving there in 1978, the songs kept coming. There were major hits for Crystal Gayle and Ronnie Milsap, and cuts for a who’s-who of Nashville nobility — Randy Travis, Kathy Mattea, Don Williams, Ray Price, and Shania Twain among them. And, of course, the on-going gig with ASCAP, which has helped make him one of the most familiar figures in the music community there.

But back in his Nashville office, there’s still a welcome for visitors from Canada. “That said, I drink Guinness now,” he laughs. “I tried to quit ASCAP four years ago, but they wouldn’t let me go. Now I’m a special consultant.”

Toronto-based singer-songwriter Jay Aymar recalls a visit.

“So I gave him the Heineken, and he told me to pick the best three songs off the record I had at the time, so I did. I played, and he listened. I guess I didn’t follow his rules of songwriting — he said, well, you’re like my pal Guy Clark; he writes great songs, but they’re not hits. If he had followed the rules, his life — and your life — would have been a lot easier.”

Murphy’s rules of songwriting?

Well, he’s written a whole book of them and Murphy’s Laws of Songwriting: How to Write a Hit Song is an essential text. And his laws — based on his studies of the successful charted songs in both the pop and country fields — are based on fact.

“Quick outline,” he says (as he has a hundred times before in interviews, articles, and seminars): “Keep the intro short — ten seconds. Use the word ‘you’ as soon as you can — the hits take an average of 27 seconds to get to that one three-letter word that engages the listener. Use basic song structures and mix them if you can. Use the title of the song within the first minute…”

Today, tall-framed and silver hair still parted in the middle, he remains a striking, vital figure. The radiation treatments have been positive; “The only problem is that I can’t sing anymore,” he tells you. “I can manage a croak, but I always loved to sing.”

His speech is now a little slower, but he remains optimistic about life — and about music. “The industry will survive,” he insists. “Music is still on the street — it’s still a vehicle for poor kids to get heard and get ahead, the same as it always was.”

There are changes, though. In his international travels, he’s become familiar with Berlin, which he sees as a relatively new music centre — “It’s what London was in the ‘50s and ’70s,” he says.

He knows that new forms of pop music — new structures, new vocabulary — are part of the changing world. “That’s cool,” he says. “But maybe it’s time I revised my book a little.”