Peter Goddard's Life in Music

The dean of pop culture criticism faces off with Bill King in a wide-ranging Q&A that includes a bit about the latest work in progress that's part memoir and part a sociology of modern culture.

By Bill King

The Oxford Companion to Music defines music criticism as "the intellectual activity of formulating judgments on the value and degree of excellence of individual works of music, or whole groups or genres."

Any musician who has been scrutinized in the public arena on a particular night or recording knows the upside of receiving a favourable review and the sting of indifference or caustic words.

“I had another dream the other day about music critics. They were small and rodent-like with padlocked ears as if they had stepped out of a painting by Goya.” - Igor Stravinsky.

Historically, when criticism came from a source most knowledgeable and well-respected the world paid attention. I like so many anticipated the musings of the most trusted. It was through insightful prose I either purchased a recording or attended a concert. It is fair to say if we both witnessed the same concert it was imperative to read the scribe’s review early morning and compare notes. There were instances when the writer heard something out of reach of my understanding or missed the action entirely.

DownBeat Magazine associate editor John Tynan, on Nov. 23, 1961, wrote, “At Hollywood’s Renaissance Club recently, I listened to a horrifying demonstration of what appears to be a growing anti-jazz trend exemplified by these foremost proponents [John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy] of what is termed avant-garde music.

“I heard a good rhythm section… go to waste behind the nihilistic exercises of the two horns.… Coltrane and Dolphy seem intent on deliberately destroying [swing].… They seem bent on pursuing an anarchistic course in their music that can but be termed anti-jazz.”

I read those reviews and Blindfold Tests and was tortured by the short-sightedness of some reviewers. Decades later, when I began publishing The Jazz Report Magazine with partner Greg Sutherland, I determined I best steer clear of record reviews knowing the survival of the magazine and my sanity depended on it.

Three voices spoke honestly to me about the local music scene in Toronto; Mark Miller of The Globe and Mail, Geoff Chapman of The Toronto Star and Peter Goddard who bounced between the two.

“I always think I'm the Tom Cruise of music - a lot of success and fans, but no critics, darling.” - Jon Bon Jovi.

Goddard was a force in music during the sharpest decades of trendy culture at The Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail. Beyond the daily columns, there were the books, Frank Sinatra – The Man, The Myth and The Music 1973, The Rolling Stones: The Last Tour 1982, The Who – The Farewell Tour 1983, David Bowie – Out of the Cool 1983, Springsteen Live 1984 – The Police Chronicles 1984, and ten others all at the centre of the developing popular music. Goddard is still very much active today and still a disciple of the vanishing art of music criticism. Trained as an ethnomusicologist, he has played piano for rock and blues bands and, when possible, divides his time between Toronto and the Limousin area of France.

You have a new book, a memoir, in the works?

It won't appear for well over a year, as I understand it. Some chapters are mostly finished but I'm sure changes will be brought to them. I generally don't like talking about things until they're there. It covers the 50 years I've been writing about the arts - music mainly but not exclusively - and yes, that makes it sound like a memoir. But my life is not entirely/really what it's about: it is about Keith Richards, and lots of rock stars make appearances, as do visual artists (Jeff Koons, Michael Snow), classical musicians (Pierre Boulez, Angela Hewitt) movie stars (John Wayne), theatre (Kenneth Tynan), and dance (Karen Kain). This life happens to have coincided with a remarkable, somewhat unfathomable, period of history the shape of which is only now becoming visible. I'm a fan of Julian Barnes' Flaubert's Parrot and Geoff Dyer's Out of Sheer Rage: These are studies/histories/whatever you want to call them, which become aspects of a narrative in a life. Dyer's subtitle is, Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence which is the snappiest way of understanding what he's doing. And there - I've said too much.

B.K.: I'm curious: with decades of music journalism and numerous books, I thought it imperative to check in with you and see what the pandemic has pinched from you.

P.G.: More writing. Indoor work, no? I've signed with House of Anansi to do a book which, at this point, is called My Secret Rock' n Roll.

B.K.: And the book captures what?

P.G.: Captures? I don't know about that. It's after the elusive: our memories, the outlines of an entire generation now becoming murky. In part, it's saying that the period that we call the rock' n roll era was part of something much bigger, broader, deeper. It was a lot of other things, one of which was jazz - and things associated with jazz. In the late '70s and early '80s, I got to meet Ellington and Satchmo. How many people have had the chance to meet Louis Armstrong? But then it was possible. What we call rock 'n roll was much more complex and much more interesting back then. A hugely important breakout of music foreshadowed a massive explosion in visual arts, video, and all kinds of other media. Roughly 40 years and two generations of people back, popular music in all its forms took over our imagination and shifted our interests.

B.K.: Does it still have a hold over us?

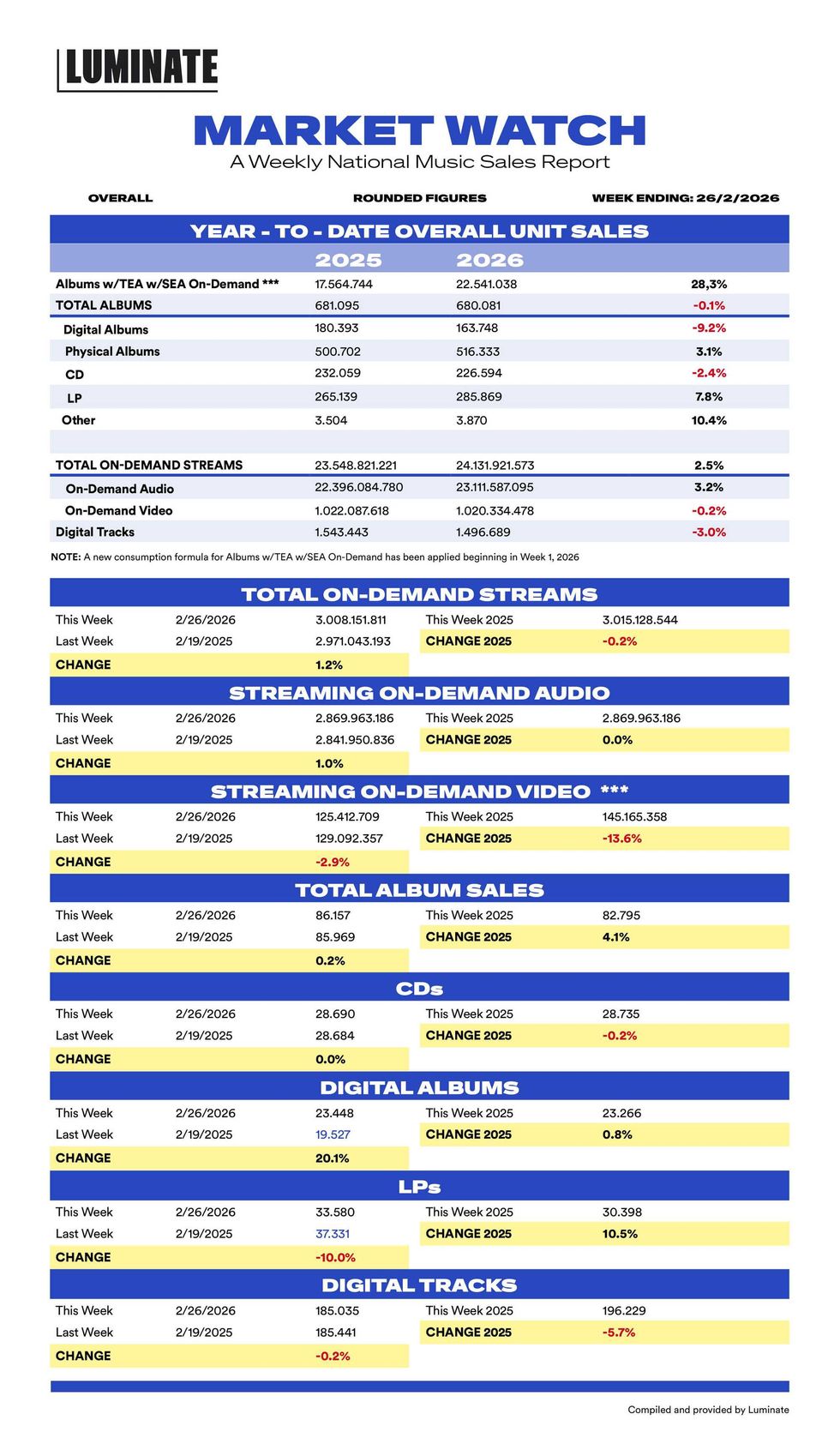

P.G.: No! The classical period morphed into another period. J.S Bach's sons led to (Ludwig Van) Beethoven, then (Richard) Wagner. It is not a bad thing, but a good thing. There is - was - a grand, almost cosmic rhythm to the ebb-and-flow of artistic periods. Impressionism to Expressionism. (Claudio) Monteverdi to (Wolfgang Amadeus) Mozart. But that evolution has been disrupted by downloading and Spotify. Algorithms rule the day. I talked recently with Sam Feldman, the influential West Cost music manager, and he told me that there is no gut instinct anymore. No one goes by their gut to find the hits.

There are many things to discuss. One of them is that the algorithms used today to identify tomorrow's hits have weakened the (A&R) process. Four months ago, Daniel Ek, who directs Spotify, headed into a controversy because he said that rather than taking money away from musicians, Spotify allows musicians to act like any other craftsman. Go home, go to your room, make a song, put it on Spotify, and we will sell it and you'll make money. As hyperbole, it sounds good, except that's not how people work. It's certainly not how classical composers and musicians work. There are those kinds of musicians that are likely to be craftsmen, the kind that can do a great ad spot, but they do not know how to put together a symphony?

For instance, jazz and classical music have disappeared as coherent forms, but even understanding what they were will disappear in the next 30 or 40 years. People will hear it and think it's great, and another soloist will come along who may be the next Miles Davis, and he will be great. But in fact, the idea that there is a thing called jazz or classical music is gone. It was a period. It was about a time in passing.

B.K.: We will not see the stages of the early development of a music form like jazz, the process, the growth, and many offshoots developed in private or on the bandstand. With gospel, blues, classical, pop, hip-hop, rap, country all at a crossroads – I don't know if there's that much more to say.

P.G.: Do you remember a guy named Gene Lees?

B.K.: Yes, I knew him through photographer John Reeves.

P.G.: I knew him a bit. He said this: "Jazz is a group of people, and when they have gone, it's dead." I think that's true and also true of rock. It's not true of classical music because it became the teaching device for all music. Jazz became part of the curriculum way too late, and rock crept in and out at the very end.

B.K.: I see us now as being in the era of sound architecture.

P.G.: Yes, I agree. Good words.

B.K.: Still, I find so much good music resides on the perimeter. Today, it's D.J.s, sometimes collaborations from a distance. With the successful ones, it's a team of six-to-eight writers and producers—and the death of the band.

P.G.: It begs the question, what happens to the art of improvisation in all of this? I think being a student right now is a challenge.

B.K.: Something is missing: That neighbourhood 'hang' with older players who lived and battled on the bandstand, who played nightly and gained from that experience far outside a practice facility is a big part of it. That's where you found your voice?

P.G.: The University of Toronto Faculty of Music is going to explore, as one of their subjects, the car and popular music. I think that's terrific; I really do. But it's like 50 years too late. As an undergraduate, I forced the Faculty to let me study with Marshall McLuhan and Geoffrey Payzant. These days, not having this background would be a detriment.

B.K.: The car is still in play. To me, it's a remarkable amphitheatre and listening room. You can have a private moment with music.

P.G.: The return of radio is another, different, thing, the podcast etc. It has to do with our ability to turn it off. "Turn-offs" are the new frontier…the new media buzz. Create the biggest "Turn-Off." We don't turn off TVs anymore; they are just on all the time. We just change channels, flip between the two or three we like and stay on them. With audio, we are very selective: we buy into this podcast and listen to that person who knows the things we are interested in, and that's it. We stop it and go silent.

B.K.: What was the first newspaper you wrote for?

P.G.: I wrote for The Varsity at U. of T. My father was a musician - and of course - I didn't want to go anywhere near the music. I ended up going into music and writing about it, and there were many reasons for that. John Beckwith told me that what made me unusual was that I was the only person he knew who wanted to write about it. I was into criticism. I love the art of criticism, and it still turns my crank—Pauline Kael in movies; Kenneth Tynan in theatre.

I wanted to apply that to music so early on I wrote in The Varsity, and then The Globe and Mail's John MacFarlane hired me – who I'm forever in debt to. The Globe wanted to update itself, so they hired Urjo Kareda and me to do theatre. After that, The Telegram hired me. The reason I'm mentioning this is that the book I'm writing covers 50 years of this. I came across my first professional review written in 1966 about singer Tom Paxton for The Globe. Just last year, I was writing for The Globe again and now The Star, again.

I certainly wasn't the hippest person out there and never have been, but I love the world of journalism – a musician-turned-journalist. A nod to Bob Dylan, I guess.

B.K.: The early years of Downbeat, Rolling Stone, Esquire magazines were about music criticism. But then advertisers became influential, and writers backed off from upsetting these money sources.

P.G.: In the history of journalism, The Spectator of London in the mid-18th century was all about music criticism. People were opera and (George) Handel passionate. What made everyone seethe and talk was music. The day that the single movie critic, a Clyde Gilmour, or maybe a Peter Howell at The Star, the last who said something, you either thought, 'Right on, bro!' or 'You are always wrong'... those days are gone. Today it's about Rotten Tomatoes and a zillion sites reviewing movies. Pauline Kael reviewed Last Tango in Paris and compared it to (Igor) Stravinsky's Rite of Spring. It was an over-the-top comparison - but she got it.

B.K.: My favourite collection of music-related writing was that of Whitney Balliett–the true poet of jazz, in The Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz 1954-2000, first published in The New Yorker.

P.G.: I have it at my place. That was The New Yorker and a special place that harboured some of the great critics. Balliett did many, many, wonderful things, including writing about Ray Charles. Ray Charles is an American success story: a blind, Black kid from Greenville, Florida, with no money who makes it. He could write like that. I never met him but knew people who knew him well and who would phone him up and ask, "What's up?" I never met him, and I regret that.

The point is, he was also the last of the jazz critics. Do you remember a journalist named Pat Scott?

B.K.: No.

P.G.: Patrick Scott was writing for The Globe in the late '60s and early '70s. Just one of the guys who would go in there. After his shift, he would go to the Colonial (Tavern), I guess. I am recreating the situation here. Anyway, he convinced somebody to allow him to come back and write a review. For about two-to-three years, Pat Scott was The Globe's unofficial jazz critic. Because of that, The Star hired him not to be the jazz critic - but the TV critic. He was very good at that too.

Pat Scott was the kind of guy who knew Bing Crosby was a great jazz singer. He was funny and trenchant, but he could also be scathing in his criticisms, but my God, put him in front of a decent piano player from the old school and he'd make your heart melt.

Scott retired from The Star. On occasion, he would write to me. I would refer to the Benny Goodman Sing, Sing, Sing concert at Carnegie Hall in 1938 – the very famous one with Gene Krupa and Jess Stacy soloing - which is one of the great moments in my life. I kept calling up the wrong date. It twisted my brain. Was it '39 or '38? I got it all backwards and always got it wrong. Scott sent me this note, "You dunce." Pat Scott nailed it.

B.K.: Do you see a future for clubs and live music?

P.G.: What was that bookstore on Front Street? Nicholas Hoare Ltd. It closed, and I happened to be on the phone with an MP or MPP about some other matters, and I said, "Why can't you guys get it together to offer tax breaks for cultural institutions?" There were a zillion different reasons why this was impossible for places like the Nicholas Hoare bookstore. It was a great place to visit. It made the selling and buying, and reading of books a magical thing. Then think about the clubs you could put in this list that are gone or just hanging on by a thread.

I hope to show people in the book that Toronto has been at the forefront of the live music scene, just behind Chicago and Memphis. The big cities in the U.S. have not been equal. Not New York. Not Los Angeles. I'm not saying they haven't had the great recording studios, and great music that has sprung from them.

New York is still one of the central recording scenes for jazz. But it wasn't the same when it came to clubs. If you wanted to go to clubs in Toronto, you'd just walk up and down Yonge Street. I've seen the lists of venues, and they showcased the history of jazz. There would be an Art Tatum or a Dexter Gordon opening on a Tuesday, and they'd be there for a week. One of the reasons was that Toronto was considered by musicians, the Black ones in particular, as a haven of sorts. They could play a week and not get hassled, as might so often have happened in the States.

Some stayed. American pioneering jazz and blues guitarist Lonnie Johnson had a club on Yorkville called Home of the Blues. On Yonge Street, we had The Colonial, The Savarin. Clubs I would visit at least once a week. Not because I'm a bar guy. I'm not, but because of the musicians playing there.