By Nicholas Jennings

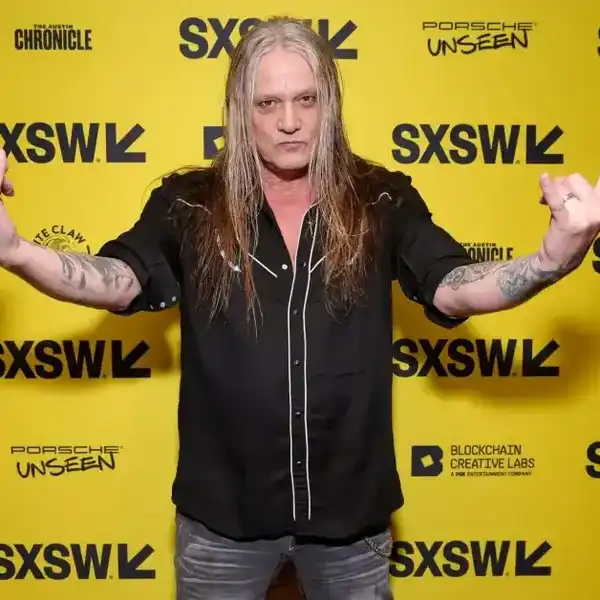

The story of rock and roll’s arrival in Canada has often been reduced to this: a good ol’ boy from Arkansas named Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins blew into Toronto with his Hawks in 1958 and cast a hypnotic spell on unsuspecting Canadian audiences.

While it’s true that Hawkins did much to popularize rock music north of the 49th parallel, there were other, often unsung pioneers here already laying the groundwork. And that’s the strength of Greig Stewart’s new book Hawkins, Hound Dog, Elvis and Red: How Rock and Roll Invaded Canada. Stewart pays tribute to performers like Bobby Dean (Blackburn) and the Gems, Frank Motley and his Motley Crew, Little Caesar and the Consuls, Les Vogt and the Prowlers and others who were all critical to Canadian rock’s early development.

Stewart also gives ample credit to the influential role played by radio disc jockeys in this country as well as booking agents and concert promoters, who introduced the first rock records and live shows to teenagers in Canada.

Importantly, Stewart delves into the years from 1951, when American DJ Alan Freed coined the term rock and roll, to 1963, when Richie Knight and the Midnights topped the charts with Charlena—the first Canadian band to do so. No book has previously focused on this crucial period (although those embryonic years were admirably covered in the three-part TV series Yonge Street: Toronto Rock & Roll Stories).

While drawing heavily on previously published histories of rock, Stewart supplements this research with fresh new interviews conducted with musicians from Hawkins, Blackburn and Vogt to Motley Crew pianist Curly Bridges, the Consuls’ Peter De Remigis and the Midnights’ George Semkiw. Other key figures interviewed include DJs Red Robinson, Duff Roman and David Marsden (formerly Dave Mickie) and Hamilton, Ont.-based booking agent Harold Kudlets, who teamed up with his London, Ont. counterpart Saul Holiff and Buffalo DJ George “Hound Dog” Lorenz to create a touring circuit for groundbreaking rock acts.

Out on Canada’s west coast, Robinson was a teenage radio DJ whose career launch coincided with the birth of rock and roll. “Bill Haley’s ‘Rock Around the Clock’ landed on my desk in July of 1955 and changed the music world,” Robinson told Stewart. “Radio would never be the same again.” Teenagers had found their sound, Robinson explained, and he was happy to provide it—even as the older generation scorned the music. “One columnist referred to me as ‘The Platter Prince of the Pimply Set,’” while another called him “The Pied Piper of Sin.”

An indefatigable Roman, meanwhile, teamed up with promoter Ron Scribner and organized summer sock hops for teenagers in cottage country north of Toronto. When he wasn’t on the air at CKEY or releasing the first recordings by David Clayton-Thomas, the Paupers and Levon & the Hawks, Roman was swooping into locations like Wasaga Beach and Port Carling and hosting dances before rushing back to the Toronto for his on-air duties. Said Roman: “I’d be in Bala on a Saturday night and be on the radio on Sunday morning welcoming everyone home from the cottage.”

Some of the book’s best stories are those connected to the Bluenote, the legendary club on Toronto’s Yonge Street. In interviews with Blackburn, singer Kay Taylor and sax player Steve Kennedy, Stewart paints a vivid picture of how the apartment-sized club, run by big city dreamers Al and Jerry Steiner, became the breeding ground for bands like the Gems, the Regents, the Silhouettes, the Five Rogues with Domenic Troiano and established itself as one of the city’s hottest night spots.

“Because the Bluenote was an after-hours club,” writes Stewart, “it attracted many out-of-town entertainers and local musicians after the bars along Yonge Street closed at midnight. Regulars still remember Stevie Wonder and the Supremes performing on the Bluenote stage to the delight of whoever was lucky to be there on those particular nights. Even Ronnie Hawkins would wander up from Le Coq d’Or on occasion.”

Through his interview with Bridges, Stewart reveals how bandleader and dual trumpeter Motley’s heavy drinking led to erratic behaviour and poor decisions that ultimately hurt the band, including turning down a lucrative film contract in Hollywood with MGM. Stewart also touches on what Bridges felt was the mixed blessing of having the cross-dressing (later transgendered) singer Jackie Shane in Motley’s band. “It didn’t bother Bridges or (King Herbert) Whittaker that Jackie was gay,” Stewart writes. “Shane was a big draw and big draws bring big money. What did bother them was that Shane was becoming increasingly flamboyant onstage.” He adds: “Also, the songs had become softer, melancholy almost, and that just wasn’t the Crew’s sound.”

Stewart packs in a plethora of fascinating historical details. Who knew, for instance, that ultra-cool one-hit wonder songs like “That Big Old Moon” and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” by Toronto’s Buddy Burke and Johnny Rhythm (a.k.a. John Rutter) respectively, were first propelled onto radio by Buffalo’s Hound Dog Lorenz, rather than a local DJ? Or that rapid-talking jock Dave Mickey was clocked at talking a dizzying 700 words per minute? “I was speaking at a speed even I couldn’t follow,” Marsden admits today.

By charting the roles of key radio and record personnel as well as the rise of pioneering bands like the Prowlers, Gems, Consuls and Midnights, Stewart has added important new layers of understanding to the history of how rock and roll first developed in Canada. And that makes Hawkins, Hound Dog, Elvis and Red essential reading for any fan or scholar of the music.

Hawkins, Hound Dog, Elvis and Red: How Rock and Roll Invaded Canada

By Greig Stewart

416 pages, including extensive bibliography and index

Published by Quick Red Fox Press