Miles Davis: The Birth of Cool

No artist has had a greater influence over jazz the past six decades than the trumpet titan. A new documentary look at the man is compelling viewing.

By Bill King

I can't think of an artist who has had greater influence over jazz the past six decades than Miles Davis.

For music, style, language and business, Davis was at the top of the game. Never one to step aside and let critics dissuade or impede his aspirations, Davis constantly retooled his band with the brightest most gifted young players of the moment.

There are those who will argue that Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Oscar Peterson were equals. But while these artists contributed mightily, Davis took note of what was happening outside the idiom and adapted his music to the world around him. He saw a useful role for electronics. He understood the potential of world rhythms, and he didn't react as a dilettante towards other musical genres. Instead, he embraced R&B, reggae, funk and hip-hop, enhancing the flavour of his own music. The late sixties he followed R&B band, The Electric Flag – early eighties – Prince!

There has been a wave of recent documentaries detailing the often-complicated lives of artists: The Two Killings of Sam Cooke and Devil at the Crossroads: blues legend Robert Johnson - yet Birth of Cool gains the edge for going the extra mile in using Cal Lumby impersonating Davis’ rasp - eloquent and at times eerie, raw street narrative. This gives us the impression we are always in the moment with Miles.

Davis’ early years were spent chasing the dream – from the Institute of Musical Arts (Julliard) after three semesters to Charlie Parker’s band replacing trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and on to singer Billy Eckstine’s swing band. Then heroin addiction and a decade under the influence and search for recovery. There were visits to the family farm and turbulent affairs.

None as compelling as his first muse and eventual wife and talented dancer Frances Taylor, whose recollections, both sweet and sour, paint a portrait of a man infatuated, deeply in love, controlling, brutal and a well of creativity.

Taylor, in her early '80s in these interviews, is as self-assured as that young dancer who auditioned for the Broadway run of West Side Story in her '20s and got the role only to have it taken from her by an often dominating and fiercely jealous Davis. Taylor would grace the cover of Davis’s seventh studio recording Someday My Prince Will Come in 1961.

Davis’ story was far different than most African Americans struggling to resist poverty. His father was a dentist, a farmer, and second wealthiest man in Illinois. He had the means to travel, to fail, to recover and reinvent himself.

Director Stanley Nelson assembled a remarkable cast – from side musicians Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and Jimmy Cobb, to writers Gerald Early, Greg Tate, Stanley Couch and Torontonian/historian Jack Chambers, who in 1989 authored the book Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis.

The grandest point the film centres on his art and creativity. As Miles' son would recall near the end of the doc, Davis never held on to the past – there were no copies of his previous recordings. He was always looking ahead. He’d met Sartre and Picasso. He sketched and painted himself, even more so in his final years.

There are also observations made by Hancock, and when listening to Davis play a ballad, he explains how the notes seem to skittle across water like stones being flipped. Miles at Newport Jazz Festival (1954) – trumpet with mute in bell of horn, caressing a microphone and the big ballad. A moment etched in history. A sound so sweet and near – empathic and personal.

The influence of singer Betty Davis, another muse, to get Miles with the times. That meant a radical departure from tailored suits to bright colors and shift to the urban clothing styles of the sixties a time when Miles became aware of the economic limitations of playing clubs and a populace more focused on rock acts where the pay was beyond boundaries. With that came experiments with funk, street rhythms, and electronics. Gone were the days of playing standards and portraying the ultra cool jazz life – in with the “love generation.”

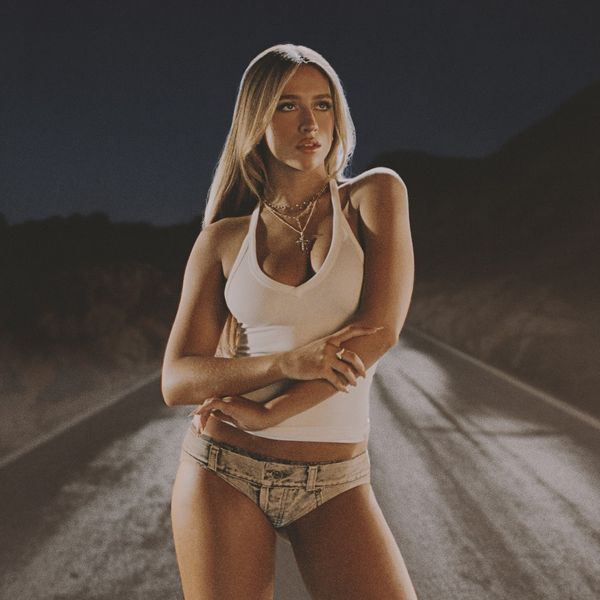

Davis understood image and projecting a mystique. Through the artwork bestowed on his recordings, he thought black. The covers were a statement and celebration of all things black - the beauty of Afro-American women.

Leaving the cinema, I thought back to the few times I caught Miles in action.

Miles came to my home area in 1963 (Louisville, Kentucky). Along with him were bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Jimmy Cobb, saxophonist George Coleman and pianist Wynton Kelly. Here was something to get worked up about. I'd been trying desperately to figure out the shifting sequence of chords over the pedal point at the beginning of Someday My Prince Will Come. Pianist Wynton Kelly was playing voicings I'd only heard Bill Evans structure. The intro seemed as if it covered the same distance as a normal solo. Kelly kept elevating the tension with each modified harmony. The right hand danced about lyrically, punctuating each tonal shift before segueing into Miles' muted trumpet. The effect was breathtaking. From that moment it was a play for the heart. The rest of the evening spun through an array of Miles' collectibles—So What, Green Dolphin Street, Joshua, All Blues, and on.

A year or so later Miles returned with an even more delectable unit, this one propelled by drummer Tony Williams. This concert was a sonic blast. People nearby commented on the seemingly radical personnel change and heated interplay. Even tunes like My Funny Valentine had a new-found tension. Herbie Hancock's keyboard harmonies were darkly dissonant textures that provided Davis with greater options. As the final cymbal crash faded, you could sense a feeling of both relief and contentment.

Every band I worked with over the following decade—whether rock, country, pop, rhythm and blues, hippie tie-died, or whatever—the players packed copies of Miles Davis' most recent recording. When Davis hit with Miles in the Sky in 1968, the transformation was underway. Drummer Williams began spinning hard rock rhythms, something unheard of in jazz circles. The next few recordings, In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew, would permanently alter the course of jazz, opening the gates to more experimental units like Michael White's Fourth Way, and others. Like nomads in a desert caravan, we waited until our point man signaled us forward.

Miles arrived at the now defunct Colonial Tavern in Toronto during the early seventies with a new band and a new sound: Jack DeJohnette, Chick Corea, Miroslav Vitous and company. The band played fierce, unrelenting fusion as Davis looked on from off-stage. Towards the set's conclusion Miles came forward, blew a few notes and retreated. All in a day’s work.

Miles never retreated musically. Star People, Decoy, Your Under Arrest, Amandla, Doo Bop, brought new faces and new sounds. During live performances, Davis began to sink into the background, giving players like John Scofield and Kenny Garrett greater latitude.

The last Davis concert I witnessed was in Toronto at Roy Thomson Hall. Scofield, Robert Irving III, Rodney Jones, Bob Berg and a percussionist whose name I can't recall were present. Davis, dressed in Zorro black attire, tucked himself in a crevice between the main stage speaker cabinets and the stage curtains. He'd occasionally bounce a few select notes from amplified trumpet into the brick wall. Most the evening he stayed buried in the shadows.

Near the end of the set, Miles arrived center stage to an outpouring of crowd adulation. The band continued pumping a mesmerizing backbeat interrupted at odd intervals by Irving's synthesizer. Davis was on the prowl. First, he replaced Irving behind the synthesizer for a few stabs at the keyboard. Then he crossed in front of the band. He belched a few notes, paused, and then looked at Berg. Berg received the eye contact as a cue to solo. As soon as Berg unleashed a sheaf of notes Davis placed a forearm on his mid-section, silencing the horn. It wasn't a hard chop but rather, notice to remain in position until otherwise notified.

As if that move wasn't strange enough, Davis then proceeded to lounge around the percussionist. The fellow sported a broad smile. Davis looked on approvingly then extended a hand in "low-five" position. The player kept smiling. Davis didn't flinch. Once again, he leveled the hand in front of the man. This time the guy accepted the bait. As the fellow slapped Mile's palm, Davis grabbed and locked it in, leaving him to play one-handed. The one hand solo went on an eternity until Davis decided to release it. The scene was weird, but for Davis, nothing out of the ordinary.

Miles Davis' music is just as popular as it was fifty years ago. With all of the advancements and innovations he brought to the idiom, not much has changed since his departure. How would Miles view the current state of jazz? I suspect he would have toyed with and reshaped and reinvented hip-hop; a music he had a hand in birthing, or he would have got into the sampling and that retro-funk thing.

That Miles turning his back on the audience thing? According to the doc, it was his way of communicating with the band – cueing transitions, etc. It was all about eye contact. Makes perfect sense!