From Juneau To Junos: Part 3

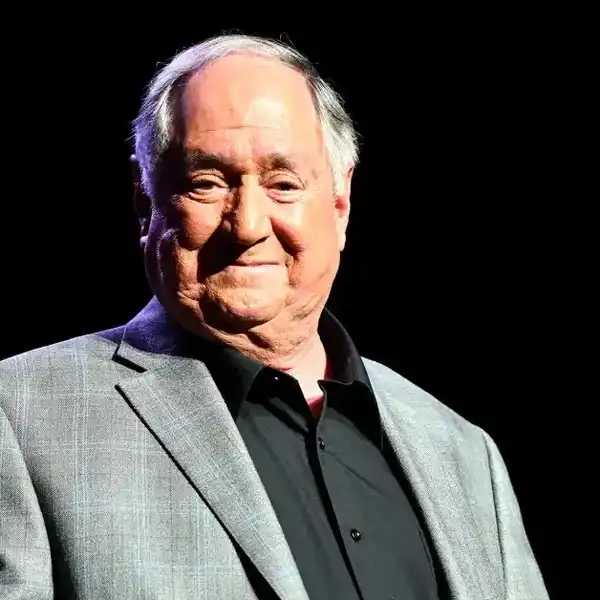

This is the third of three parts revisiting the colourful history of Juno Awards over the years, researched and compiled by noted author and music industry documentarian Martin Melhuish.

By Martin Melhuish

This is the third of three parts revisiting the colourful history of Juno Awards over the years, researched and compiled by noted author and music industry documentarian Martin Melhuish. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

The fact that the landmark 50th anniversary of the Juno Awards is being celebrated at all is remarkable. The fact that the ceremony will arrive with a fair measure of the pomp and circumstance it deserves, albeit online, is almost miraculous.

Allan Reid, President/CEO at the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (CARAS)/The Juno Awards and its associated charity, MusiCounts, along with his cohorts at the organization, have had to stay agile in reacting to the ever-changing rules and regulations of a pandemic that has had such a devastating effect on live performance and social gatherings.

This year’s celebrations follow a year when the emergence of Covid-19 resulted in the cancellation of the 2020 awards which were to have taken place at SaskTel Centre in Saskatoon as part of Juno Week in that city. The plug was pulled just three days before the March 15 planned date. It was the first time that the Junos had been cancelled since 1988 when the event was rescheduled from the late fall to the early spring. The 2020 Juno winners were eventually announced on June 29 as part of a virtual ceremony through CBC Gem, hosted by Odario Williams and Damhnait Doyle. Postponed until this year was the Canadian Hall of Fame induction of Jann Arden, who has hosted the Junos a couple of times herself: 1997 (Copps Coliseum/FirstOntario Centre, Hamilton) and 2016 (Scotiabank Saddledome, Calgary). It’s no doubt a proud moment for Allan Reid who had signed Arden to A&M Records during his time in the record biz.

Flexibility and nerves of steel have always been necessary attributes for anyone tasked with organizing this, the biggest night on the Canadian music industry calendar. It seems that there’s always an off-speed curve ball high in the pitch count. The 39th Junos were held at Mile One Centre in St. John’s in April of 2010 at a time when a cloud of ash from a volcanic eruption in Iceland had caused the closure of most of the airports in Europe. Bryan Adams was unable to fly in and made his Humanitarian Award acceptance speech by satellite.

The Junos have some historical precedent for operating by the seat of its pants. In 1975, the year the proceedings were first televised, host Paul Anka arrived just prior to the show having not read the script, yet winged it admirably with the help of some hastily assembled cue cards.

It has also operated without the seat of its pants, like in 1981 at Toronto’s O’Keefe Centre [Meridien Hall] when country singer Carroll Baker, who had launched her career at the 1976 Junos with a stunning live performance of the song, I’ve Never Been This Far Before, arrived on stage in a chauffeur driven Rolls Royce with Ronnie Hawkins who ripped his snug-fitting tuxedo pants from stem to stern as he clambered out of their loud luxury ride.

Not enough northern exposure to cause a controversy on this night, but over the years there have been a number of unexpected side shows surrounding the Junos which have caught the attention of the pundits in the media.

At the March 29, 1992, Junos at the O’Keefe Centre hosted by comedian Rick Moranis, Bryan Adams and Tom Cochrane, two of the hottest guitar slingers on the charts at the time, were going mano a mano in a number of the categories. The Globe & Mail dubbed it “The Shoot Out at the Juno Corral.” There was a feeling that there might be an industry backlash to the much-publicized comments Adams had made suggesting that the Canadian Content regulations are the breeding ground for mediocrity during his press conference in Sydney, Cape Breton prior to the start of his 13-date Canadian leg of his Waking Up the World tour earlier that year. The showdown was actually a bit of a dud. Cochrane’s album Mad Mad World, and his hit single, Life Is a Highway, earned him four Junos. Adams left with three awards, including the first-ever Special Achievement Award. The only surprise was that Cochrane took home the Single of the Year Juno when most people thought Adams’ global hit, (Everything I Do) I Do It For You, was a lock in that category.

One of the earliest contretemps, which in hindsight worked out for the best for both sides, involved the recognition of the music and artists from Quebec at the 1975 Juno Awards, the first year they were televised by the CBC. It was pointed out that, though many of the top selling artists from Quebec received a number of nominations in all categories, they were almost totally ignored when it came time for the awards to be given out on nationwide TV, even though most top Quebecois acts often sell thousands more records than the top acts in the rest of Canada just in their own province. The lack of representation of those acts at the Junos angered most of the music community in Quebec. Following the 1974 Junos held in the Centennial Ballroom of Toronto’s Inn on the Park Hotel on March 25, David Freeston wrote in the Montreal Star, "The Quebec industry people I've spoken to have almost unanimously expressed emotions ranging from incredulity to indignation. It is, in short, a scandal: the feeling prevails that yet once more, the rest of Canada has snubbed, or at least overlooked, Quebec's achievements."

The feeling ran so high that eventually the Association quebecoise des producteurs de disques inc. (AQPD - the Quebec Association of Record Producers), headed by Yvan Dufresne, pulled out of the Junos and moved to set up its own awards program under the name Le Grand Prix de disques quebecois. Though CARAS was not happy with the split, they indicated their willingness to lend expertise and human resources to the Quebec association to help institute an equitable voting procedure for an awards system in Quebec.

In the late fall of 1977, the AQPD disbanded to become what is today’s Association quebecoise de l’industrie du disque, du spectacle et de la video (ADISQ), which produced its own gala, first held on September 23, 1979, at Montreal’s Expo-Theatre, to present the Felix Awards, named after Quebec’s, most celebrated singer/songwriter, Felix Leclerc. The Junos presented an award in the category of Best-Selling Francophone Album from 1992 to 2002 before changing the category name to Francophone Album of the Year. Notably, Montreal-based, songwriter Luc Plamondon, known for his early work with Celine Dion, and for co-writing popular French rock musicals like Starmania and La Legende de Jimmy with the late French composer Michel Berger, was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame at the 1999 Junos at Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum (FirstOntario Centre) at which Dion dominated the awards and performed twice.

Dion hosted the 22nd Junos at Toronto’s O’Keefe Centre on March 21, 1993 and brought a laugh from the crowd when she took to the stage and told them, “I’ve been very excited since I was asked to do this. I’ve been working hard on everything… polishing up my speeches and working on some very funny material and then, when I got here, they asked me to do it in English!”

Anne Murray, who leads the pack in the number of Junos received over the years with 25, spent some time away from the Junos in the early '80s which caused much handwringing and speculation. The clamour got so loud that at the 13th annual Juno Awards in April of 1983 at Toronto’s Hilton Harbour Castle, comedic actor Alan Thicke, a friend of Murray’s and co-host that evening with Burton Cummings, commented sarcastically, “Anne Murray is in Los Angeles conducting herself, as usual, in a manner that does honour to the Canadian recording industry.”

At the same venue in November of 1986, this time with comedian Howie Mandel hosting, Anne Murray returned to the fold. “So, this is where you hold this thing every year! Finally found it! As some of you know, I’ve won a great many of these. I just want you to know that I’m proud of every one.”

There have been times when Junos never quite made it to the trophy cabinet of the artists for whom they were originally intended.

At the 1998 Junos in Vancouver, hometown hip-hop trio Rascalz (Red 1, DJ Kemo, Misfit), who were nominated for Best Rap Recording (Cash Crop), first presented in 1991 to Maestro Fresh Wes (Symphony in Effect), got the word that the category was not one of those included in the TV broadcast and would be presented at the Gala the night before. They felt that it disrespected the genre, which was dominant at the time, and decided that, if they won the award, they would refuse it. They made their way to the Gala to learn they had won but were late in arriving. They missed their chance to officially refuse it on stage, but later in the media room their manager Sol Guy read the statement that they had prepared: “In view of the lack of real inclusion of black music in the ceremony, this feels like a real token gesture towards honouring the real impact of urban music in Canada. Urban music, reggae, R&B and rap, that’s all black music and it’s not represented at the Junos [on TV]. We decided that until it is, we are going to take a stance.”

Things changed the following year when urban music made its first appearance on the Juno broadcast from Hamilton as Rascalz took to the stage with their latest track, Northern Touch, featuring Choclair, Kardinal Offishall, Thrust and Checkmate, subsequently picking up a Juno for Best Rap Recording for the song.

At the 19th annual Junos on March 28, 1990 at Toronto’s O’Keefe Centre hosted by Rick Moranis, duo Milli Vanilli were destined to become the first artists to have their Junos disqualified after it is revealed that Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan didn’t sing on their International Album of the Year, Girl You Know It’s True.

Following the awards in 1978, country singer-songwriter Stompin’ Tom Connors held a press conference at which he boxed up his six Juno Awards – five of them for his consecutive wins from 1971 to 1975 as Country Male Vocalist – and returned them to Juno organizers, CARAS. He was protesting the recognition on the Junos of Canadian artists who live in the U.S. “They are taking opportunities away from the people who choose to be proud to live in this country and to do their work here,” he declared. He didn’t stop there. Before he died in early March of 2013, he left specific instructions that the Junos were not to celebrate him after he died.

When artists hit the podium to react to a Juno win in the excitement of the moment, their reactions are usually off the cuff and seldom boring or predictable. It was a member of the West Coast jazz scene who made arguably the pithiest of all Juno Awards acceptance speeches. Upon being notified in 1993 that he had won in the category of Best Jazz Album for his My Ideal album project, saxophonist/flautist P.J. Perry declared to an astonished audience during the televised awards show: “That’s some deep shit! Wow, this is too much! This is the first time I’ve ever won anything!”

Often there are patriotic thoughts:

Jim Cuddy of Blue Rodeo in 2012 [as the band is inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame]: "We have travelled a very long and beautiful road and this country has given us so much. We've met and played for amazing people, seen some beautiful things, and we've had so many unforgettable experiences. But the true measure of our success is in this room, all the friends I see out there, all the friends I know are watching. We've always, always from the beginning felt supported and appreciated in this country and we are extremely grateful to be able to make music together with all of you. Thank you."

Alanis Morissette in 2004 [the year she hosted and wore the flesh-coloured body suit with fake nipples and pubic hair to bring attention to what she felt was an over-reaction to the infamous nipple slip incident involving Janet Jackson during the Super Bowl half time show that year]: “My intention in taking part in this show with you tonight is to let you know how deeply grateful I am to have been born and raised in this blessed country and to honour the brilliance that is birthed from such a place.”

Neil Young in 1982 [on being inducted into the Hall of Fame by Francis Fox, Minister of Communications]: “I have this one feeling tonight. I’m proud to be a Canadian.”

Gordon Lightfoot in 1973: “I’ve been accepted in my native country on a scale I never dreamed possible. I’m going to sing the praises of Canada far and wide for as long as I can.”

Sometimes they think of dear old Mom:

Burton Cummings in 2016 [on his induction into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame]: “Thanks folks. That is just remarkable. I share this and dedicate this to my hometown of Winnipeg. I lost my mom two years ago and I think she is up there looking down… I have been so lucky. I have been surrounded by so many good people.”

The Weeknd in 2016: “I want to thank my mom. Thank you for putting up with all my bull for so long. I thank you.”

Drake in 2010 [on winning the New Artist of the Year award which he dedicates to his Mom]: “She’s responsible for not only the artist I am but the man that I am.”

Sometimes they are whimsical:

Nickelback (Ryan Peake) in 2009 [on the band receiving the Juno Fan Choice Award]: “This is a good one. This is why we didn’t get a real job. This is why we still don’t have a real job.”

Presenters Matt Dusk and Measha Brueggergosman in 2005 [on the category Adult Alternative won by Sarah Harmer]: “[Dusk] We both have no idea what it means to be an adult alternative act. [Brueggergosman] So, I looked up adult alternative on the Internet. Do not do that, especially in front of your kids or at work.”

Ron Sexsmith in 2005 [on accepting the Songwriter of the Year Juno]: “I knew if I kept showing up every year, they’d have to give me one of these things.”

Kim Mitchell in 1990 [on accepting the Male Vocalist award]: “I think of myself more as a white boy yelling.”

George Fox in 1990 [on accepting his Country Male Vocalist Juno]: “I’ll tell you folks, a couple of years ago it was a big deal for me to take the cow into the vet.”

Carole Pope in 1984 [on winning Female Vocalist award]: “I’d like to thank CBS and True North Records and my creator... Max Factor.”

Sometimes there is introspection:

k.d. lang in 1990 [while accepting her Country Female Vocalist award]: “I have to confess one thing to you people: for me, it has nothing to do with awards. It has nothing to do with record sales. It has nothing to do with what category I’m in. I just love to sing.”

In looking back over the 50-year history of the Juno Awards, I was reminded of an article written back in the 70s when the Canadian music industry was in its salad days. It was by an American music journalist by the name of Robert Weinstein and the headline read “Who’s Got the Bop in Beaver Land – Quick! Hum Some Canadian Music.” His basic premise in the article was that Canadian music doesn’t exist and for the most part Canadian artists push “an already well-entrenched American sound.”

A glance at the nominees for this year’s Junos reveal just how far the Canadian music industry and its artists have come since that first modest gathering at the St. Lawrence Hall in Toronto half a century ago. Canadian music, for the most part, draws sustenance from the wide expanse of the country, its cultural diversity and its unending struggle against change perpetrated by outside forces and cultures – usually American. Listen to the Guess Who’s American Woman from that early Juno era for comment.

A few years after that song became a number one hit on both sides of the border, its singer took note of a possible reason why the Canadian music industry seemed to be advancing at a brisk pace. Following his award wins at the Junos at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto in 1977, Burton Cummings quipped, “Don’t let anyone tell you that things don’t happen fast in Canada. In just 75 minutes, I went from Best New Male Vocalist to the Best Male Vocalist of the Year.”