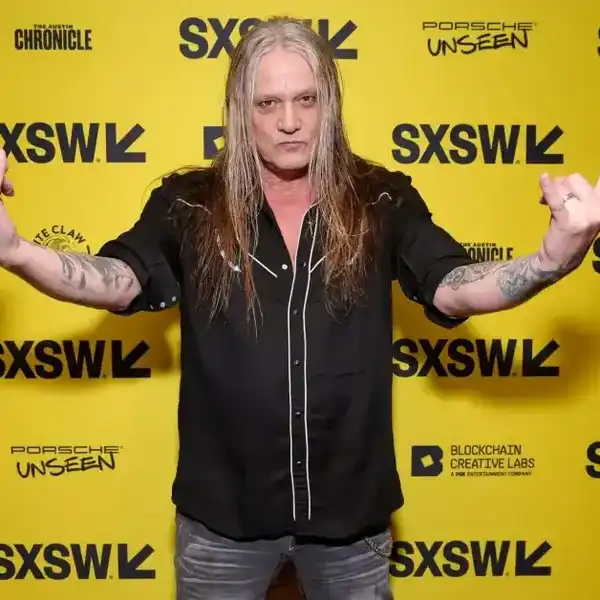

The Eric Mercury Interview, Conducted By Bill King

We'd known the past few months Eric was well on in his battle with cancer, and yet we hoped an intervention of some sort would have either stalled or rendered him whole once again.

By Bill King

We'd known the past few months Eric was well on in his battle with cancer, and yet we hoped an intervention of some sort would have either stalled or rendered him whole once again. To us, Eric was a man who wore dignity like a finely tailored suit. All class and well-spoken. Sadly, pancreatic cancer took him down, in Montreal, on March 14. He was 77. What follows is an interview Bill King did with Mercury three years ago.

Those thirty years backstage summers at the Beaches International Jazz Festival brought us all together. Publicist Martine Levy was close to the Mercury family and reserved seating in a sponsor's tent for Toronto's black singing history, the Jacksons, Jay Jackson and family, the Ellis family – Bobby and brothers. Those tables roared with laughter and shared stories. "You remember when?" Radioman Mark Ruffin would occasionally fly in from New York, Betty and Jerry from Kansas City, and the gang was complete. As the wine flowed, so did the soothing strains of a Sam Cooke classic, a Marvin Gaye anthem, a Betty Wright remembrance. It was a gathering of the doo-wops and soul men and lazy days hidden from the sun and music pounding only yards away on the main stage. At the centre of the gathering was Eric Mercury. Eric lived in Montreal and made the summer trek to be with old friends and talk about days when you played five sets a night, and the women loved a man at the centre of it all. Three years back, I cornered Eric for this interview. At once, out of curiosity, knowing his life was rich with events unknown by most Canadians and that of a long-time fan.

Electric Black Man stands as a milestone ‘60s recording and penetrating music document from a Canadian singer who should have been an international superstar.

Musicians Arthur Lee of the band Love, Jimi Hendrix, the Chambers Brothers, Black Merda, Ritchie Havens were all from a generation of black men who stepped off the “soul train” and forged a new direction talking brotherhood and immersed themselves in an emerging counterculture. The music they made was first stamped ‘soul psychedelia’ by white critics yet Toronto native and singer Eric Mercury had a different take on this new sound.

Bassist Stu Woods (Bob Dylan, Don McLean, Janis Ian) and I were roommates on 88th Street in Manhattan in late 1968. The two of us shared a mad passion for all genres of music. The Band’s Big Pink played endlessly as well as anything from Miles Davis, Jeff Beck, and organist Jimmy Smith. At times I would purchase a recording based solely on the cover art. Mercury’s Electric Black Man found its way straight to a Hi-Fi bought with few dollars on 42nd Street.

Stu and I repeatedly dropped the needle. There was something in those grooves that cracked with urgency and directness. It was the vocalizations of unknown singer Eric Mercury. It was the raw power, the seriousness, the brutal honesty of each shattered word that stuck in the head. It was a voice that sourced dozens of iconic singers from across the soul and blues spectrum - stashed in the heart, processed, and then let it go.

White folks embraced Paul Rodgers – a pure, blue-eyed-soul rock diamond. Black people didn’t know it, but they had Eric Mercury – a true roots man pushing the boundaries and waiting in the wings.

I cornered Eric and transported him back 50 years for a bit of reflection and understanding. That understanding – folks you missed a great recording now re-mastered and available. A side note, Eric went on to star in Jesus Christ Superstar, write and produce for Don Hathaway and Roberta Flack, write for theatre and on and on.

Bill King: It’s the late sixties. What made you decide to abandon the Toronto scene and travel to NYC?

Eric Mercury: The Soul Searchers featuring Diane Brooks and Eric Mercury became a very popular R& B / jazz organ quartet in the Canadian music scene. As time went on, Diane and I became restless with the rate of success or lack thereof. I suppose the pinnacle of our existence was getting booked into the hottest NYC club known as Steve Paul’s Scene. The members of the band were Steve Kennedy on tenor, baritone and background vocals, Terry Logan on guitar and vocals, William (Smitty) Smith on Hammond B3 organ and vocals and Eric (Mouse) Johnson on drums and vocals as well.

When we arrived in New York, we were well received, and the show was packing them in. Tiny Tim was the emcee, and on the bill: The Doors, The Chambers Brothers, and The Soul Searchers. I was confident that I was as good or better than anyone else singing in the show. The audience fed my opinion. We quickly became crowd favourites and were rebooked then opened at Scene East on New Year’s Eve in the Delmonico Hotel on Park Ave. I was sure we were going to get signed by a major label, but it was not to be. Shortly after and many other disappointments, Diane fell in love with a hairdresser who told her he’d take her to the moon (go figure) and she left the band, leaving me as the sole frontman. We took a booking up in Halifax Nova Scotia, and during that time, I heard a Richie Havens recording that made me hunger for life in NYC.

I wanted to try songwriting but was heavily discouraged by everyone except Smitty. I needed some instant soul replenishment and crushed by the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King. I promised myself I would be a part of the “black power movement” taking place in “Amerika.” I couldn’t wait to get out of Halifax and begin figuring out how I would pull off my exit from Canada, and my legal entry into the U.S. The straw that pushed me out was the band took a gig without me at a club on Victoria St. (The Mercury Club) Can you believe that? I left the city a few days later with C$52 and got a ride with two hookers to NYC.

B.K: Were you able to move quickly into that lively music scene?

E.M: I hit the ground running when I got there. I knew no one except some groupies that had assured me that “if I was ever in town and needed a place to crash” .......... turns out they didn’t have a place to crash for themselves and so, hanging in the West Village and East Village began. I always looked for places to jam, and places to live.

I met guitarist Elliott Randall during this time, and whenever I could, I’d introduce myself to club owners on Bleecker St. That was where the action was or St. Marks Place in the East Village. I found the bus station on 8th Ave to be handy if you could evade the cops all night and I could.

I needed sleep, and found an abandoned Studebaker under the Westside Highway (Henry Hudson Pkwy) and made that my official residence. Every day it was up and out into the street early trying to meet musicians willing to join me in forming a new band. Then one night I spotted a photo of a band that looked interesting – Blood Sweat & Tears and, of course, I recognized David Clayton-Thomas. I walked down the stairs of the Café Au Go Go and stood in the club’s doorway, David saw me and said, 'Over there stands a guy who's one of my favourite singers in the world.' I ran up on stage, and we did a sort of impromptu jam for a few brief minutes, and the managers, Bennett Glotzer and Dennis Katz grabbed me as though I was the second coming. I have David to thank for that; my life changed from that moment.

I was taken everywhere with them after that. I met Clive Davis that night (president of Columbia Records), and he invited me to the annual CBS convention that year; slated to be in San Juan Puerto Rico. All the signed acts played live for the company. Janis Joplin (with Big Brother and the Holding Company) - you’ve heard of them, haven’t you? - O.C. Smith, Chicago Transit Authority, Spirit, Chambers Brothers, BS&T of course and many more.

I bunked with trumpeter Lou Soloff, and that began a lifelong friendship. Back on the streets, I’d found the beginnings of a band, some kid named Rik Zerringer (who soon after became Rik Derringer) and Elliott Randall, Colin Walcott, and a four-piece horn section. Shortly after that, I met Howard Solomon of the Café Au Go-Go. He had seen my performance with BS&T and asked if I needed a booking at his club and I jumped at the chance. He allowed us to rehearse every day if we chose and of course, we did

B.K: Did you have other connections within the record industry?

E.M: I had no real connections in the record industry beyond record execs that had heard or seen me perform with the Soul Searchers - Clive Davis who I had met at the BS&T show in the Café Au Go Go, but to call was him was not possible. He had long forgotten me, and I had nothing to show for signing purposes.

B.K: How did you secure a recording deal?

E.M: I took the gig at the Café Au Go-Go with a band I had cobbled together from the street -eleven pieces in all and not knowing how they would pay them. I met a guy that owned a record store, Shelly Weiss at Washington Square, and 6th Ave; he was a friend of music producer Gary Katz (Steely Dan, Joe Cocker, Laura Nyro).

We rehearsed in the basement. Weiss became a close friend of mine and invited Gary, and another friend Eddie (Shoes) Choran to see me perform at the club. Hugo and Luigi (songwriters/producers Luigi Creatore and Hugo Peretti) also attended. Hugo offered me a deal immediately. Gary had told them about me. They witnessed my performance, and a deal was sealed.

Meanwhile, “Shoes” had just started working a gig with the Stigwood Organization. They sent “Shoes” with a cheque for me to pay the band and signed me based on that performance. I now had a record deal and management.

B.K: Having Canadian roots - you could be whoever you chose to be. George Olliver played his version of soul mixed with psychedelia. Rick James and others who inhabited the Toronto’s Yorkville music scene of the ‘60s travelled in a lane of their choosing. Were you as independent thinking? The U.S. had its superstars, and they had a particular playbook and ground rules.

E.M: Back in the Soul Searcher days, I did write with Smitty. I didn't have any songs as of yet. I had to prove I was a songwriter to satisfy Hugo and Luigisince - I had told them I was also a songwriter. Over the weekend, I wrote my first song, Electric Black Man and a few others. I sat in the apartment of a woman I had met and grown close. Before I played the songs for them in their offices, I suggested we "cut to the chase." They asked what I wanted for signing, and I answered, $25,000 and a Green Card. Done!

B.K: Electric Black Man caught music critics off guard. What was it they took issue with?

E.M: At that time, there was no conversation about “black” anything in the artistic community except for the Last Poets. To raise the subject was the kiss of death in the business. My views had hardened because of Martin Luther King’s murder and the influence of the Black Panthers and the Black Muslims. I had problems with the idea of rocking my music and being black at the same time. I didn't know there was such a thing as "black music" within the industry. My education had just begun.

B.K: Would you call this “soul psychedelia”?

E.M: "Black Rock" was how they began to refer to it. There were only a few black musicians that were involved in the creation of it playing in what was called "Two-Toned" bands. R&B radio didn't even play Jimi Hendrix who had become a pal, along with drummer Buddy Miles (The Electric Flag).

B.K: The choice of songs? How was this made? From your original Night Lady to Donovan’s Hurdy Gurdy Man.

Producer Gary Katz took me to meet a friend of his who worked at Peer Southern, a major publishing house. They played me a few songs, and I loved Hurdy Gurdy Man. Katz and “Shoes” had some other friends that were songwriters and performers: Bobby Bloom, (Montego Bay, Heavy Makes You Happy, Again and Again) and Marty Koopersmith ( Jay and the Americans). They brought us You Bring Me to My Knees. Lou Stallman contributed Everybody's Got the Right To Love. Gary Katz has great ears. H&L would eventually sign him to Avco Embassy as head of A&R.

Gary and Shelly wrote A Long Way Down. I wrote Tears No Laughter, Enter My Love, Electric Black Man, and co-wrote Night Lady with Steve Tyndall. Elliott Randall introduced me to Tyndall, a close friend who brought me Earthless. Shelly Weiss became my road manager.

B.K: How did you make it to Stax Records?

E.M: When we received our first royalty statement, all of the reports were different, indicating that there was some foul play involved. Management (Robert Stigwood Organization) decided I should move to Stax Records as Stax was trying to get into the crossover market. Stigwood was representing the Staples Singers. After a visit from Stax producer Steve Cropper, I was traded to Stax Records. Viola! I was on Stax, a place that always appealed to me.

B.K: Your vocals on Electric Black Man are as powerful and gutsy as any male vocalist of the era – Ray Charles, Paul Rodgers, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding. From where does this come?

E.M: My vocal heroes were always R&B/blues singers. From Hank Ballard, Ray Charles, Don Covay, Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, Lou Rawls, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, etc. from years of stealing their influence and covering their songs. That's how I crafted my vocal style.

B.K: Did your tour behind the recording?

E.M: Eric Mercury Birthright toured the U.S. extensively playing all of the big venues; the Fillmore East and West more than a few times; Boston Tea Party and many more, including The Whiskey Au Go Go in L.A. I continued to tour and perform long after I was at Stax. One live recording at the Fillmore East coming soon. Stax recorded me live @ the Houston Astrodome most likely lost in the recent fire in the Universal Studio warehouse.

B.K: How was the band for the recording selected?

E.M: Gary, Elliott and I picked the studio musicians from those we liked and had a connection. Randall brought Harvey Brooks in on bass and Richard Greene on violin and the drummer, whose name I don't remember.

B.K: How long did you stay abroad before returning to Canada?

E.M: I lived in the USA for 34 years and returned to Canada in 1997-98. I had a young child after a failed marriage - ten years in LA, nine years plus in Chicago and New York for altogether 15 years and 22 months in Cuba.

B.K: Looking back – how do you see the ‘60s and time spent?

E.M: My musical years were born in Canada in a church where I sang in the choir. My dad was one of the presiding ministers, and my mother served as a deaconess. I loved all the vocal groups of the day - Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the Coasters and Drifters, the Heartbeats and the Spaniels and the rest. My first vocal group consisted of Bobby Dean (Blackburn), and another group I had and was proud of was with Jay Jackson as a member.

Electric Black Man is the first of eight recordings and will never die. Inside of it lives the heartbeat of the times conceived inside a political, social, and counter culture. It's the same kind of ‘times’ feel we're living today. I'm still a hippie. Still angry, and yet full of love for justice! It's students of music who have refocused on this recording. The recording and I will be back shortly.