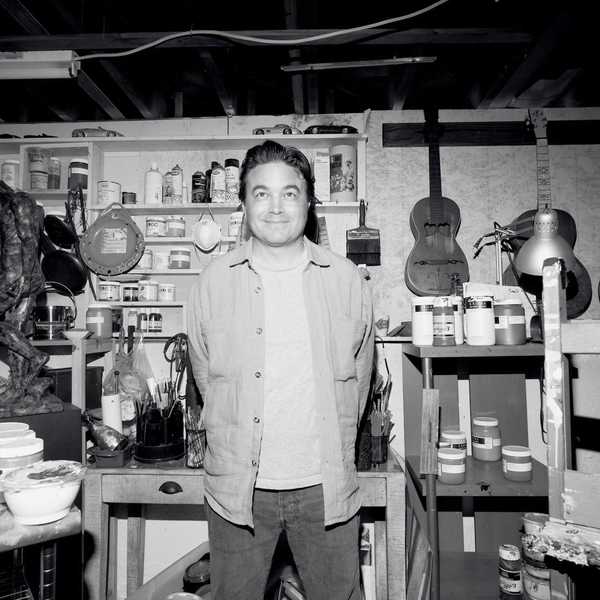

Dan Hill: The Grammys, A 42-Year Retrospective

Dan Hill is one of Canada's most successful singer-songwriters with a trophy cabinet of awards to show for it. What follows is a very personal accounting of the Grammys that is perhaps best exemplified in his latest song, What About Black Lives? He debuts this and other songs from a new collection in a live-stream from the El Mocambo a week today (March 25).

By Dan Hill

The Grammys, a 42-year retrospective, 1979 – 2021

Dan Hill is one of Canada's most successful singer-songwriters ever and author of the book I Am My Father’s Son: A Memoir Of Love And Forgiveness. He was recently inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame. What follows is a very personal accounting of his history with the Grammys, written in his own words with research assistance from (son) David Hill, Nathan Williams and Dirie Dirie). He recently released a new, 14 song album entitled 'On the Other Side of Here' that contains the topical and evocative song, What About Black Lives? He is set for a simulcast from the El Mocambo in Toronto a week today (March 25).

ON MARCH 11, 2021, The Weeknd—whose single Blinding Lights is the first song to stay on Billboard’s Top 10 for more than a year (65 weeks and counting)—announced that he was permanently boycotting the Grammys. “Because of the secret committees,” he explained in a statement to the New York Times, “I will no longer allow my label to submit my music to the Grammys.” He also vowed to refuse to perform in the future at the awards.

It comes as no surprise that The Weeknd (Abel Tesfaye) wanted nothing more to do with the effete Grammys. His latest release, After Hours, was 2020’s best-selling album and continues to break chart records and garner critical acclaim. He was an absolute shoo-in to win both Song of the year and Album of the year. Instead, not only was The Weekend robbed of both Grammys—incredibly, he was not even nominated.

Bizarrely, March 14th’s 2021 Grammy awards appeared to devolve into a personal feud between The Weeknd and the Grammys. Aside from the absence of a nomination, he didn’t receive the expected invite to perform at the award show. In response, The Weeknd wrote a statement on Instagram reading: “Collaboratively planning a performance for weeks to not being invited? In my opinion zero nominations = you’re not invited”.

No doubt, this anonymous Grammy committee was still smarting due to what The Weeknd said last November, shortly after experiencing what was arguably the most stupendous Grammy gaffe of all time, when his exclusion was made public.

The Weeknd addressed the tainted organization this way: “You owe me, my fans and the industry transparency.’ The Academy’s deeply condescending response? “We understand that The Weeknd is disappointed…and can empathize with what he’s feeling.’" But, the CEO added, "Every year some “deserving” acts miss out."

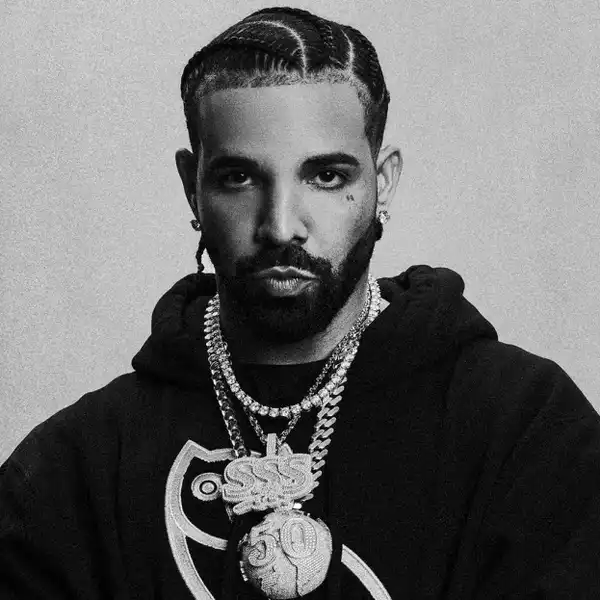

In the wake of this 2020 Grammy imbroglio, both The Weeknd and Drake went public, calling out the Grammys for being corrupt while demanding that it be replaced with a new awards show. All things considered, Drake’s comments— “We should stop allowing ourselves to be shocked … by the disconnect between impactful music and these awards”—were surprisingly measured. Especially given that back in 2018, due to his utter disgust with the legions of jingoistic Caucasian Grammy judges who operate “cloaked in secrecy,” he presaged The Weeknd’s move by refusing to submit his number one album, More Life, for consideration.

When Drake returned to the Grammys the following year and won for Best Rap song (for a song that he pointed out wasn’t even rap) he used his speech to say, “we’re playing in an opinion-based sport, not a factual-based sport…. The point is, you’ve already won if you have people singing your songs word for word…you don’t need this [trophy] right here.”

And so, when Drake says ‘the disgraced Grammys are “like a relative you keep expecting to fix up but they just can’t change their ways,” his words hit me like a blow straight to the solar plexus.

Recent Grammy debacles notwithstanding, there is still no higher honour in the music business than winning this most coveted Award. It carries far more status than how many hits you’ve amassed. Just look at how often music journalists kick off their stories with the number of Grammys an artist has won. And so, the magnitude of the decision to walk away from the show illustrates just how incensed both The Weeknd and Drake were and how deep their desire is for change.

On top of forgoing the status the award could bring, both artists risked public and media backlash for their positions, thereby taking a potential hit on their career for the sake of (in Smokey’s words) “telling it like it is.”

How curious that just last year the former Recording Academy CEO Deborah Dugan said that the institution is guilty of “outrageous conflict of interest,” going on to point out that “one artist who initially ranked 18 out of 20 in the 2019 song of the year category” was permitted to sit on the nomination committee reviewing her own song. Hardly a surprise that this artist made the short list. Former academy member Rob Kenner has made similar statements, “The industry has a lot of built-in conflict of interest,” he observed. “Who’s actually in the recording academy? It’s full of older white men.”

Yet, it’s what Sean “Diddy” Combs had to say at a pre-Grammys gala in 2020 that pierced my heart the most: “Every year, y’all be killing us, man. I’m talking about the pain; I’m speaking for the all the artists here…. The amount of time it takes to make these records, pour your heart into it – and we just want an even playing field. For most of us, this is all we got. This is our only hope.’

Public Enemy’s Chuck D. echoes Diddy’s words but with even more venom. “The folks who control (the Grammys) are mostly old, rich, white, male executives with corporate agendas who look at these awards as toys and trinkets.” Little wonder that the last Black artist to take album of the year was Herbie Hancock in 2008. And the last Black woman to snag this award was Lauryn Hill, in 1999. And Black recording artists are not alone when it comes to being totally fed up with the Grammys. Even the massively successful Billie Eilish recently announced that she did not want to be awarded any more Grammys.

Ouch. This entire Grammy fiasco left me feeling flattened by a wallop of Deja-vu.

I wasn’t in the slightest surprised that The Weeknd’s best-selling song of the year wasn’t even nominated for Song of the year. It’s not as if we haven’t seen this pattern played out time and time again. But the strangest intermingling of bitterness and nostalgia washed over me, as I felt the memories of 1979 creep in.

I could only commiserate silently as I recalled the year my smash hit single Sometimes When We Touch hadn’t been nominated for best song either. (Billy Joel’s Just the Way You Are was the winner.)

Out of curiosity, I compared the 40-year stats on both Just the Way You Are and Sometimes When We Touch, keeping in mind Drake’s trenchant observation that “we’re playing in an opinion-based sport.” Nevertheless, just as in sports like basketball or baseball, songs over a span of decades have statistics. The numbers tell the story, they don’t lie, they don’t have opinions. And due to the ubiquitous, up-to-the-minute streaming and downloading stats, we can easily compare how certain songs have fared over several decades.

This is what I discovered: Sometimes When We Touch has over 8 million more views than Just the Way You Are. And I was further gobsmacked to discover that between the massive amount of covers and fan lyric videos, the total number of views for Sometimes… surpasses 100 million.

Even today my own version racks up endless downloads and streams, thanks in part to Dolly Parton saying in a recent interview that Sometimes When We Touch is her favourite song of all time, one she wishes that she had written. Thanks, too, to the reactionary Elon Musk, who during an internet feud with Bill Gates close to a year ago tweeted out my song.

But unlike The Weeknd, I wasn’t completely shut out of the Grammys the year Sometimes was released. I was nominated for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance. I was up against Barry Manilow and his rendition of Copacabana.

Manilow won.

What bothered me most about that decision was the fact that Sometimes… is, in technical terms, one of the most demanding songs there is to sing. Apart from the verse’s idiosyncratic phrasing and the huge vocal range it requires, it’s almost impossible to successfully navigate the starkly vulnerable, passionate and intimate lyrics. If you over-sing it, you sound maudlin and mawkish; if you under-sing it, you sound soulless, clinical and detached. For most performers, it’s an impossible fit, a script too tough to match. Some great singers have attempted it—Rod Stewart, Tina Turner, Donny Osmond, Demis Roussos, Tammy Wynette, Ginette Reno—but none of them, including Barry Manilow, has come remotely close to having a hit with it. (Manilow’s single release of Sometimes… tanked.)

Just for fun, I downloaded my 1977 video of Sometimes When We Touch. My memories tumbled back in a disjointed mishmash of images from 44 years ago, when I was 22. I remembered that I had just completed the recording of my single the day before. I’d laid down vocal after vocal, day after day, night after night, for a week straight. Never had I spent so many hours in the studio singing one song. I sang until my head became dizzy and spinning. Until my voice felt drained of every ounce of emotion, every semblance of soul.

After watching my video, I downloaded Barry Manilow’s video version of Sometimes When We Touch. Then I downloaded his video for Copacabana. Was his vocal performance in that song superior to mine? Would Manilow himself have thought so?

Well, the truth is that even Manilow understood that, at best, he was an average singer. Indeed, when asked about his singing prowess in a 2006 interview, Manilow answered, “I’m good, not great…. Sinatra is great. Judy [Garland] is great. Tony Bennett is great. I’m pretty good.”

With Jay Z’s assertion that “Men lie, women lie, numbers don’t,” rattling in my brain, I discovered that the lifetime stats for my “Sometimes” video shows well over 32 million views; Copacabana has 5.1 million views. I may not have won the Grammy that year, but my single has achieved what was impossible to predict even when it was at its peak of popularity. “Sometimes…” has become a classic. Which dovetails neatly into what Drake said in his Grammy acceptance speech: “You’ve already won if you have people singing your songs word for word…You don’t need this [trophy]…”

At this juncture in my life, now pushing 70, I’m too old to play coy or hide behind false modesty. So I’ll simply say this: Barry Manilow is a better piano player than I am. And I am a better singer than Barry Manilow.

A week before the 1979 Grammy Awards, L.A.’s most influential music critic predicted that Barry Manilow would win for best male pop vocal performance. What’s revealing is that this critic hated Manilow’s music, eviscerating the singer (who’s as sweet and kind as he is self-effacing) constantly.

So why would this same critic predict that Manilow would win the Grammy for that category?

One reason.

As an industry insider, he must have known something about the shady, back-room politics that governed the award. He likely knew The Grammys were fixed but couldn’t say it openly. Did he simply recognize that a Black or bi-racial non-American artist winning the best male vocalist (outside of the racialized R&B category) would not be allowed in the system? Were Black artists, no matter how deserving, expected to toe the line, stay in their lane?

I realize now that winning or being tapped for a Grammy has nothing to do with the artist. It had nothing to do with me then, just as it has nothing to do with Drake or The Weeknd now. This Grammy disaster is exponentially bigger than the three of us (and too many others to name). This cuts straight to the heart of systemic racism, going far beyond racism in the Grammys or in the entire music business.

This is, of course, a microcosm of the racism visited upon all Black people for the past 400 years. It was not that long ago when a young Quincy Jones, unable to rent a hotel room, had to sleep in a funeral parlor beside 19 corpses. Not long ago that the great Sam Cooke became the first Black artist booked to perform on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, only to see the national guard called in due to the number of bomb threats. So tragic that Cooke’s prescient A Change Is Gonna Come was not released until a few months after his murder—a crime that sadly will also always be shrouded in a secrecy.

While Black artists have made real strides since then there is still much injustice and inequity. And so, we are all connected, however disparate and subtle the ways. Every single one of us—be it Drake, The Weeknd, Babyface, John Legend, Tupac, Biggie, Beyonce, Jay Z, or me—has undergone a similar yet uniquely personal journey, battling the scourge of racism the best way we know how: with courage, discipline, intelligence and a drive and responsibility to honor our musical gifts.

Unquestionably, Drake, The Weeknd, and I come from totally different worlds, so many generations apart, and we create our music in completely different ways—which is as it should be. But when Drake sings about wrestling with the terms of his fame (“Soon as you give ’em your soul, you blow up and they say you’re selling your soul” and “I sit in a box where the owners do. A boss is a role I’ve grown into”), it brings me right back to what I wrote at 21, when I too was struggling with the existential vicissitudes of massive stardom (“Dear Caroline, I thought my songs would change the world, instead of slowly getting rich, off the emotions of young girls”).

And within the selfish confines of my career, as far as the Grammys are concerned, how can I complain?

I’ve been nominated twice. I won once. One out of two? I’m good with that.

And I’ve been fortunate enough to spend a lifetime doing what I love and being well paid to do it.

After all, it’s a business that Jay Z says is ten times harder to succeed in than making it as an NBA player.

But more than that, all famous Black performers, me included, have to recognize and be grateful for the power of our global platform.

When someone like Drake, The Weekend, Kanye, or Nicki Minaj summarily condemns the Grammys, their words ricochet around the world, galvanizing people of all races while enlightening and infusing them with optimism, defiance and pride. In this way, the system meant to block Black artists from winning Grammys ends up backfiring: the ensuing scandal, the overpowering whiff of corruption, blows back into the nominating committee’s wizened faces.

Every new revelation of racism gives all of us who are fortunate enough to be, in Sam Cooke’s words, “economically empowered” a far greater opportunity to pull back the curtain on the hidden systemic barriers and inform the world as to, in Marvin Gaye’s immortal words, “What’s Going On?” And thanks in no small part to Drake and The Weeknd, we’re answering him loud and clear.

When we question what the Grammy judges have against Black artists (especially urban and hip-hop creators) there’s one essential through-line. We can trace it back to the time when African citizens were kidnapped and ripped away from their families, to be sold off as slaves in North America, beaten and driven down onto their scraped and bloodied knees, picking cotton in oppressive, 100-degree heat.

We’ve endured a history totally unlike most races. The resulting traumas, scars and humiliation have played a seminal role in influencing the way all Black people relate to and create music. Digging deep into the depths of our tragic and violent past, we ultimately heal ourselves by addressing, processing and coming to terms with our own vulnerability, our litany of unspoken wounds and fragility. In doing so, we manage to transform our pain and profound hurt into shimmering, redemptive and transcendent pieces of art.

This kind of brutal honesty and raw emotion drives the songs we write. It’s a big reason why our music resonates so powerfully with audiences around the world. However, this trademark soul and passion that informs our singing and song writing is, largely, a double-edged sword.

Why?

Because the mainstream media (largely consisting of male, Caucasian, privileged music critics and, yes, Grammy judges) is wholly threatened and discomfited by songs of this depth.

Little wonder that the lyric I wrote at 19, “Sometimes when we touch, the honesty’s too much,” touched a raw nerve, upsetting and totally discombobulating the typically buttoned-up, and oft times racist, music critic. At the same time, it resonated deeply with Black artists, such as Tina Turner, George Benson, Kool and the Gang, Jeffrey Osborne, Cleo Laine, Oscar Peterson, and even the Filipino boxing legend Manny Pacquiao—who felt moved enough to record their own versions.

It’s no coincidence that it was Sam Cooke who, overwhelmed with horror and sorrow when he saw Black prisoners in shackles, doing life-risking slave labour, immediately wrote, “That’s the sound of the men, working on the chain gang.” Nor is it by chance that the late Bill Withers showed us real personal courage looks like in his classic hit, Use Me, whereby he opens up about the unmitigated shame deep in his psyche with the words, “It’s true, you really do abuse me, you take me to a room of high-class people, and you talk real rude to me.”

And who else but Prince would dare to be so vulnerable, with this heartbreaking lyric: “Maybe I’m just too demanding, maybe I’m just like my father, too bold, maybe I’m just like my mother, she’s never satisfied … this is what it sounds like, when doves cry.”

So, The Weeknd is continuing in the Black songwriting tradition when sings, with such ache and longing, “I’ve been tryin’ to call, I’ve been on my own for long enough, maybe you can show me how to love, I'm going through withdrawals, I look around and Sin City’s cold and empty, No one’s around to judge me.”

Borrowing once more from my line, ‘The honesty’s too much’, these kinds of nakedly soulful lyrics are far too raw and real for the Grammys.

Furthermore, an opaque shroud of anonymity shields the Grammy judges, the ultimate and unassailable arbitrators of who does and who doesn’t qualify for being “the best.”

How many of them are disquieted, envious and resentful of the Black artists, who, since time immemorial, have revealed their deepest wounds through their art? How many were raised to reproach the “unmanly” need for intimacy, to disdain and eschew all manner of vulnerability, and to mock instead of empathize when people reach out for help in times of suffering?

All this to say that music fans around the world hunger for the kind of honesty and bruising emotion threading through the lyrics of Drake’s, Lil Baby’s, John Legend’s and The Weeknd’s songs. Because we are raised to never express uncomfortable emotions, it’s deeply therapeutic to hear seminal artists address these similar kinds of feelings. It reminds us that we are not alone in the world in our moments of self-doubt, alienation and disillusionment.

It’s hardly a coincidence that both Drake and The Weeknd are the most successful recording artists on the planet. And rightly so. Drake and The Weeknd, it’s your world now. Embrace it. Breathe it in. It’s a wonderful and blessed life when your talent, your artistry, and your utter authenticity have captivated millions around the globe.

As for me, I am first and foremost a passionate fan of music, utterly and completely. Just like I was when I was 3 years old, when my mom and dad had to pry me away from their hi-fi stereo, where I’d be huddled against the speaker, transfixed by some Billie Holiday record, inculcating her melancholic phrasing and singing it back with uncanny precision.

Tonight, I ran like a fiend on my treadmill, jacked up by American R&B and hip-hop music blasting full volume. It’s just by some crazy, random twist of fate, some arbitrary roll of the dice, that I also happen to be a singer, songwriter, musician and author.

It’s too late for me to stop now.

What can I say?

I love my job.

I guess I was born lucky.

Dan Hill - Postscript

Dan Hill's new 16-song album titled 'On The Other Side of Here', released February 12, 2021 on Sun and Sky Records, distributed by Warner Music/ADA, is available on all major digital platforms.

Physical copies (CD) of ‘On The Other Side Of Here’ are available for purchase on Dan’s official web shop.

The powerful and evocative single What About Black Lives? is available here:

Dan’s memoir‘I Am My Father’s Son is available for purchase via Harper-Collins Canada.

Follow Dan on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Dan Hill Official website