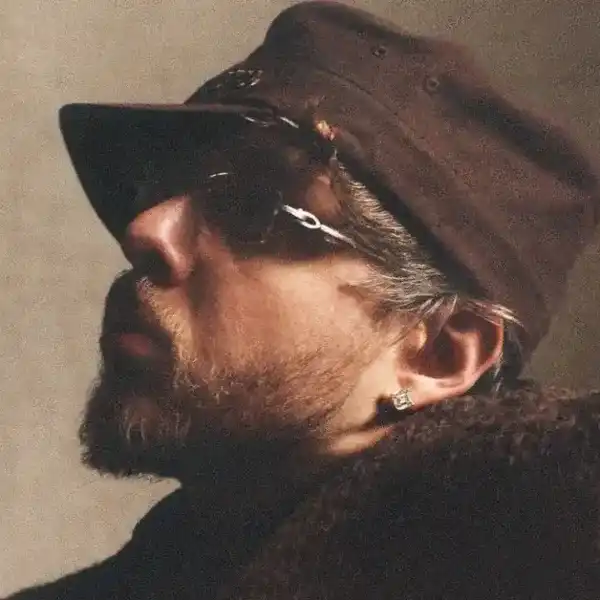

A Conversation with...Holger Petersen

In this wide-ranging chat, the veteran broadcaster, record label head, and roots music authority reflects upon the fascinating career spawned by his passion for music.

By Bill King

Upfront, I’d like to say, I’m in the pit working on a book of interviews – Talk! Conversations in All Keys – and Holger Petersen is an example of those who make up the backbone of our music industry. Just when I think I’m nearing the finish line, another iconic Canadian figure emerges, and it’s, 'let’s chat time.'

Holger needs no introduction – damn, it’s his 50th anniversary on radio! How has he managed? My intention in all interviews is to probe deeper into the person and their passion for art – the art of music journalism, concert photography, production, recording, labels, management, and the artists.

It’s not always possible. Yet, every interview leaves you with a glimpse into them, and their chosen path in life and, hopefully, each generation that follows will get a glance into our remarkable past.

Enjoy!

Bill King: When thinking about who has served 50 years on radio – I’m thinking the late Wally Crouter and his time at CFRB, yet you’ve been on CKUA as long. Has your Natch’l Blues show run the same distance?

Holger Petersen: It marks the 50th year of Natch'l Blues being on the air. I was hanging out at CKUA a year before that, just kind of learning, observing and meeting people. And then an opportunity came for me to do a blues show and that's when that started. It was in 1969.

B.K: These are your teenage years?

H.P: I was eighteen when I started hanging out at CKUA and nineteen when I started doing the blues show.

B.K: How did you get there in the first place?

H.P: The longer story is, I was a record collector. I loved the British Invasion bands. I started collecting 45s and reading as much as I could while going to high school - playing drums with a few local bands and then finding out about this course at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology called Radio and Television Arts. They had just started it, and this was the second year. And as soon as I found out about that, I said this is precisely what I want to do. I was able and lucky enough to get into the program. During that first year of the program, I started broadcasting into the cafeteria at (Northern Alberta Institute of Technology) NAIT Radio and it was one afternoon a week.

The bug was there. I loved doing it. And then somebody told me about CKUA, and I started listening, and they were doing Progressive FM kind of programming and would answer the phone on the weekends. The announcer at that time was Tony Dillon-Davis. You could phone him, and I told him what I was doing at Nate, and he said, 'oh, you want to come and see what we do here and hang out?' And that weekend I was there, we became friends, and I just ended up hanging out there a lot. At the same time, I offered my services to Nate Nugget, the school paper, to write about music and started writing reviews and doing interviews. And then CKUA began to broadcast those interviews. They did a year-end show where they got the announcers together and talked about your favourite records, and mine were all blues records. The program director said, “Oh, would you like to do a blues show?” And I said, “absolutely.” So Natch’l Blues started.

B.K: Did you grow up in Edmonton?

H.P: Since I was seven.

B.K: Before that?

H.P: I was born in northern Germany on this little island on the North Sea, Pellworm Island, right by the Danish border. When I was five, my family immigrated. We lived in Verdin, Manitoba, and Boissevain in Manitoba and then Edmonton.

B.K: What was dad’s occupation?

H.P: He was a mechanic. He was a trained mechanic. And when he got here, he found that you could make a lot more money working in the oil patch. So that's what he did. He started working in the oil patch and hence moving around a little bit. That's tough work and away from family. Eventually, he had a service station in Edmonton, and that's where I worked in my high school years.

B.K: Changing tires?

H.P: Changing tires and pumping gas.

B.K: That British Invasion. It had to be The Yardbirds - The Who?

H.P: There were a couple of stores on the seedier side of Jasper Avenue that serviced the jukebox in central and northern Alberta. When I found out about those two stores, I would head down on Saturdays, and they had several bins of 45s that were five for a dollar. You could thumb through them and pick out five. They were the more obscure ones that didn't make it onto the jukebox or else the ones that were kind of worn and taken off them. That's when I started to look at the labels and realized, you know what? There was a thing called the producer, and there were songwriting credits - recorded in England and those kinds of things.

B.K: Those were great times. I would hit Main Street and Woolworth's, there were be 45’s in bins next to men’s sox, and occasionally there would be a lone EP. One had Oscar Peterson on it playing Sheik of Araby – another track, the Original Jazz Band - Livery Stable Blues, and that gave me an insight into the outside world. Little Stevie Wonder. A lot of times, it was the B-side that caught my attention.

H.P: You’d go home, sit down in your basement, flip them over, and have friends over and say, guess who this is?

B.K: How have you managed to stay on the radio for 50 years? There have been significant changes.

H.P: CKUA is a unique station in Canada. It's the first public broadcaster in Canada. It started in 1927, and it predates CBC, and it started on the University of Alberta campus. And then the government took it over, and it became a provincial network. They've always had professional standards and hired professional people. It was the perfect place for me to learn; the jazz people, the classical, and people who were interested in all kinds of music. It had this fantastic record library, probably second only to CBC. It was an excellent education, and I always wanted to maintain a relationship and contact there because it was so inspiring.

The people who were around me were people you could learn a lot from. Plus, we could bring people into the studios and record. Not only was I doing Natch’l Blues, but they were open to ideas and I did other programs. I did an interview program for many years. They had an agreement with the musician’s union where we did a series for several years and were able to bring musicians in and pay them scale to do radio shows. At that point, my interest in wanting to do production allowed me to undertake radio shows and radio production. I would record people as they came through at various venues and also bring them into our little studio at CKUA. We had a budget where we could record multi-track professional sessions.

B.K: You were subsidized by the government?

H.P: Yes, by the provincial government.

B.K: How many cities and towns in the network?

H.P: Right now, I think there are thirteen FM transmitters. Back then, there was one active AM transmitter and FM didn't come into it very strong then.

B.K: Is programming divided between Calgary and Edmonton?

H.P: Yes, we have a studio in Calgary, and we go back and forth. There are announcers in both places and announcers like Terry David Mulligan. His show is from Nanaimo and we have somebody in Austin. We have different people that submit shows as well.

B.K: When you said interviews, I guess early on, certain artists would be readily accessible - a B.B. King or Jimmy Page?

H.P: You're right. Back then, I interviewed Led Zeppelin twice. The first two times they came through Edmonton, it was pretty much just a matter of showing up and the promoter would take you backstage and introduce you to somebody and ask, “do you want to do an interview?” Sure. It was kind of like that.

B.K: It was the same for photographers having access. And then by maybe 15, 20 years ago or so, it became difficult getting access. Managers and promoters shut certain media down and now it's wide open with smartphones.

CBC, thirty-three years?

H.P: Thirty-three and a third in February.

B.K: How did you line up with CBC?

H.P: I was doing my show on CKUA and a CBC producer was tuning in and thinking, this might be a good fit for Saturday nights on CBC. There was a slot that came open - he approached me, and we submitted. We got rejected, with some suggestions. Submitted again, got rejected, and then the third time got denied, they said, “thank you very much.” Then about two weeks before the first show aired in December, whatever that was nineteen eighty-nine, eighty-eight, I got a call saying we've changed our mind and you're on in two weeks. It was amazing to get that call.

B.K: It's a fantastic run; you have become an institution. At CKUA, in the beginning, were you initially volunteer, or did you get paid to do the gig?

H.P: I was a volunteer. And then, I did get paid.

B.K: Nearly everyone I interview, hoping to gain a career in music is trying to get a foot in the door. You still have to apprentice. Most have a record collection or inhabit a record store and usually bug the proprietor.

When you look back on those early interviews, are there any that stick out?

H.P: So many. As you well know, working musicians, especially if they're involved in fringe styles of music and jazz, blues, whatever, it's always driven by the music. When you talk to musicians who you love and respect them and their music, it's different than doing pop interviews and it's different than having a controlled ten minute whatever it is. To answer your question, I've had published two books of interviews published, and my favorites, I guess, are in the first book, which has a bonus track with Mavis Staples and Ry Cooder. I always loved talking to them and interviewed them more than once.

I also think Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones. I flew to London and I had been trying to set up an interview, and eventually, it worked out. We talked about the blues, and it was wonderful, and then he started talking about the Stones, which was a bonus for me, and that was a great interview. But there's so many generous people and so many smart people.

B.K: Did you catch Muddy Waters?

H.P: I almost got him. I saw Muddy a couple of times in Edmonton. I was supposed to do one with him, and he bailed and then ended up having it rescheduled on the phone. Muddy had a baseball game playing in the background, turned up loud, and the phone on one ear. He wasn't paying a lot of attention. I probably picked up about ten minutes of that. But yeah, Muddy.

One of my all-time favourites has been B.B. King. I interviewed him and had a chance to do that six or seven times, and he was always so gracious. And as you know - very smart and a great perspective on things. He did a lot of media and didn't know shy away from that. I have to say, every time I interviewed him, he was so warm, and it was so heartfelt that at the end of it, I'd have a smile on my face for a week. I’m thinking, seriously, this is B.B. King.

He invited me on the tour bus a few times. One time he was in Edmonton and played a club and asked me to listen to some music with him and hang out. Just a beautiful, gracious person.

B.K: I interviewed Dr. John over the phone and later, when I hit playback, I realized I couldn’t transcribe because there was so much surrounding noise. I wrestled with my emotions then asked his publicist could we do again, and it happened to be a Godsend. The “doctor” was coming to Toronto. We met in his hotel room, and it was magic. Has this happened to you?

H.P: Not quite that kind of story, I don't think. I have found that if you've interviewed somebody the second, third, fourth time, it breaks the ice a lot more. I've been fortunate. I have had the opportunity to interview a lot of people more than once.

B.K: Do you pry more out of them a second time?

H.P: Yeah. You know, it always comes down to a few basic things like - did they have a good day? How much time do they have? Are they in a rush, and how relaxed are they, and what's going on in their life, and personal life? Is there a new record, a book, or whatever they want to talk about, and what are they enthusiastic about?

You never really know how it's going to go until you start.

B.K: What about the disaster interview?

H.P: I’ve had a few, I think. Probably Chubby Checker not too long ago - I pursued that. I wrote that it was great that he's still out there, which he still is. We had set it up. No problem, you've got eight minutes, and here are your first two questions.

B.K: He gave you the questions?

H.P: Well, not him but the manager. And then we said, we'd like to do something a little more in-depth - it is a national radio show. They said OK, well, then you’ve ten minutes, and that was it.

The first two questions were leading questions about how important he is and what he's doing and stuff like that. Those things are beyond your control. He's going to do that and move on right away. He's got his schedule.

B.K: There’s his position and connection with history next to Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

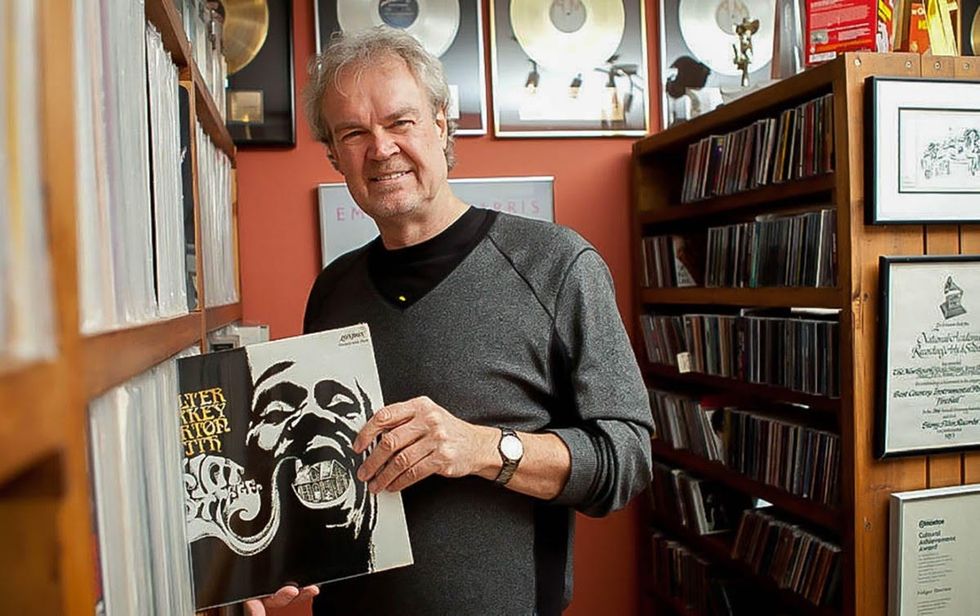

H.P: With my desire to do productions, the first record I did was in 1972 with Walter Shaky Horton with Hot Cottage, which was licensed to London Records and Transatlantic Records in Europe. That kind of really got me going. I was inspired to be in a studio with a blues legend like Walter Shaky Horton and to be part of that whole process - it meant a lot to me, and the blues bug was there.

In the early 70s, mid -70s, there were a lot of blues artists who were still alive and weren't being recorded very much, and one of those was Johnny Shines. I produced a couple of records with him and Roosevelt Sykes, and I would bring them up to Edmonton - get some gigs for them and then go in the studio and record solo records with them - solo piano, solo guitar. But every time I did that, I would be investing my own money, of course, and then you try and find an outlet and try and find somebody to license the record. Eventually, I was doing pretty much the photography and the packaging and liner notes and delivering the record. That was one step away from starting your label.

In the fall of 1975, Alvin Jahns, who was a dear friend had a business accounting background, and we were in a garage band together, I said, “if I start a record label, would you help me on the business side of things?” So, we started a partnership back then. The first record came out in early 1976. In the first three years, I only put out three or four records. But then I saw there were labels like Rounder Records and Flying Fish Records and Sugar Hill Records that weren't getting proper distribution in Canada. Nobody was working them. I started licensing from them, and the first company was Flying Fish, and they allowed me to put out several of their records. And then Rounder Records noticed that and said, well, if you're doing Flying Fish, do you want to do some of ours?

B.K: Would you do the pressings?

H.P: Yes, we weren't importing them. We were pressing and doing publicity and helping the artists try to get some gigs and that sort of thing.

Then Stony Plain became a more significant operation. The fact that we were developing a catalogue with some international artists, I think, went along until about 1985, and then I met Ian Tyson. I'd known Ian over the years, and he was ready to do an independent record and asked me if I would help him. That was Cowboyography, which became a gold and platinum record and just huge. I thank Ian every day for opening that door for me. I'm happy to be still working with Ian all these years.

B.K: Was that your most significant success?

H.P: Yes. Stony Plain was a roots music label that specialized in blues and singer-songwriter - different styles of roots music and also had respect for first singer-songwriters from Texas.

I was working with Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt - it was terrific. That opened the door to working with Emmylou Harris and Rodney Crowell on individual albums when they weren't tied to major labels. They would record an independent record and maybe put it out themselves, and we were kind of the Canadian label that made sense to work with. That was true in the case of the first Robert Cray records, also Lucinda Williams, Joe Ely, and Asleep at the Wheel.

B.K: There were actual stores you could stock and sell product in.

H.P: Yes.

B.K: They had blues sections, then it got to be much more difficult.

H.P: Absolutely. Of course, it is.

B.K: It’s mostly streaming. What about mail order?

H.P: There is that, and off-stage sales are still a big part of it. Alvin and I sold the Stony Plain catalog to True North last year, and they took over July 1st. Alvin is retired, and I'm continuing to do productions and act as executive producer for artists I have been working with for a long time on behalf of True North. I'm pleased with that relationship and delighted not to have the burden of the administration.

B.K: Where do you see yourself now? You have all this history behind you. Where are you at in your life now?

H.P: I think the relationships that you develop over your long career continue to be rewarding and just meeting great people and knowing great people. I'm very proud of the fact that I've worked with people for a long time and in a lot of different situations and that they are friends. I think the most rewarding is seeing some success with people that you feel deserve it as artists and also as people and being part of perhaps that successor, initiating ideas that result in records coming out, concepts, and supporting your friends.

B.K: What kind of sound system do you have at home?

H.P: I have two houses. I live in a house with my partner and the house next door is my office. I still maintain my offices there. I get up in the morning, and I've always got records I haven't heard - albums, and vinyl wherever I go. I tend to inhabit used record stores and seek obscure CDs and reissues, whatever. In the morning, I tend to put on a vinyl record or two often. I'm always looking for inspiration for my radio shows.

B.K: You always want to keep it fresh.

H.P: I love going through and finding that one track - number four on side two or something that hits you and you think wow, this is great, I'm gonna play this next week, and oh, that leads to this, and that ties in with this. Before you know it, you are kind of excited about being able to present a few new things.

B.K: What do you look for in a track that excites you?

H.P: Certainly, the songwriting and the commitment, the vocal responsibility - the instrumentation, whoever is doing the solos or whatever or, something that's fresh and something new. Still, that vocal commitment is essential, and I know you've kind of paved the way with your writing and work on that. The stuff from the R&B and gospel tradition, especially the gospel tradition, where people show a commitment to what they're doing, they're not just making a pop record or calling it in assuming, I have to do this.

I go to Memphis once a year. I go to Nashville, Austin, places like that, and always seek out people I can interview you are not going to run into on the road. You ask about what is rewarding, and that keeps me going - the kind of things to be able to sit down with a Don Bryant or Dan Penn or somebody like that. That’s a pretty fantastic opportunity.

B.K: I remember bluesman, Robert Lockwood Junior. He would come to a local music store in Smyrna, Georgia, and would check for updates on sales of his records. They would stock maybe ten copies. I didn't know who he was, and then he asks me for ten dollars. I thought to myself how cool was that – I bought the record and it was so good!

H.P: Yeah. All that information is so readily available now to everybody. You go down those rabbit holes and see all those videos and everything else. In our day, it was different.

B.K: The last question, Sister Rosetta Tharpe. You talk to experts and collectors, and they will say she revolutionized guitar playing and had a significant influence over Chuck Berry and others. Did she hit you that way?

H.P: Very much so. I came through people like Long John Baldry, who was doing Up Above My Head with Rod Stewart. He recorded that with Rod Stewart in 1962 or 63 or something. When I heard her, I listened to some material that I had previously heard. But I don't think I've ever heard anybody that had that kind of enormous impact. There are people along the way, of course, but she - absolutely when you see that footage of the American Folk Blues Festival in Britain and see that footage of her on the railway platform – it’s so powerful.

There's so much great material by her too - some of its spotty. There's even that one CD that has her wedding ceremony.

When she got married, there was a public wedding - they sold tickets. It would be like the Houston Astrodome kind of environment. I think it was in Washington, D.C., come to think of it, a baseball stadium in Washington, D.C. that's available on a CD.

I have again CKUA to thank for that because they had that vast library and allowed me to order whatever I wanted. You're going through like the Down Home Music catalogues, from Chris Strachwitz, in California. They would write these reviews on these Japanese reissues, and I’d think, that sounds interesting – I’d order that, and it would end up in the CKUA library. That was a real and constant inspiration all the time - new records coming in.