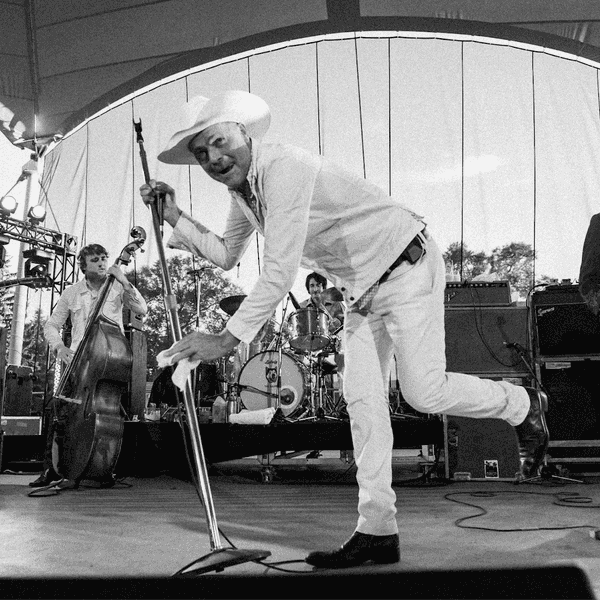

A Conversation With ...Randy Weston

Pianist-composer Randy Weston (America's African Musical Ambassador) passed away September 1, 2018, after a 70-year career that saw him establish a strong presence on the international jazz scene.

By Bill King

Pianist-composer Randy Weston (America's African Musical Ambassador) passed away September 1, 2018, after a 70-year career that saw him establish a strong presence on the international jazz scene. His far-reaching performances took him from the US to Africa, Canada, Europe, Asia, the Caribbean, and South America. Over some 50 recordings as a leader and his numerous compositions recorded by Max Roach, Dexter Gordon, Cannonball Adderley, and others, Weston's music embraces the rhythmic heritage of Africa. Since his visit there in 1961 for a three-month, 14-country tour, he travelled, performed and lived on the continent and considered it to be an infinite source of musical inspiration.

We sat down for a long conversation in the summer of 1993, and it was both enlightening and inspirational, addressing the roots of African American culture.

BILL KING: Your music has its roots in African culture and modern jazz from a period when jazz was on the rise in New York City. Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Duke Jordan and Willie Smith were some of the most celebrated artists of the time. What motivated you to study your cultural heritage and the music of jazz?

RANDY WESTON: My interest in cultural heritage came from my parents and growing up in Brooklyn. The music was everywhere. There was no television or disco at the time; everything was music. You either listened, played or danced, or you did all three.

Growing up in Brooklyn as a young child, there was so much music. It was at dances, on the radio, in clubs and rehearsal halls. It was a fantastic period of all kinds of music — calypso, Caribbean music, gospel, jazz, blues, the whole thing.

B.K: What is the connection between African music and jazz?

R.W: For me, jazz is African music in the United States. It's just an extension of Mother Africa, and wherever you find her children, whether it's Brazil, Jamaica, Trinidad, Puerto Rico or the US, you'll find this approach to music and life. It's the African way of life. Spirituality, polyrhythms, call and response — they're all there.

B.K: How have Africans received your music?

R.W: I've been very fortunate, because the first time I performed in Africa, I had an African drummer with me who was a specialist in African drumming. If the audience couldn't understand some of the things we did on top, they could relate to the rhythm of the drum.

B.K.: Your formal training was in classical music — Bach, Beethoven and Mozart. Was it challenging to study as a child?

R.W: It sure was. When I was 12, I was six-feet tall and had big feet. I wanted to be outside with the other kids playing baseball and football, but my father made me practise. He was a tough guy. There was no escape — thank God.

B.K.: Who were the jazz pianists who influenced you?

R.W.: The first person I tried to play like was Count Basie. And then Nat King Cole. Tatum influenced me, but I could never play like him. His daring and mastery of the instrument and the things he would do with the rhythmic pulse affected me. Monk also influenced me and, after him, Ellington.

Those are the leading piano players, but there were other musicians, like Coleman Hawkins, who had a significant impact on me. It was an era of many great artists — trumpet players, trombonists, drummers, bass players and pianists.

B.K: You've said you view jazz as part of the black man's Africanization of European instruments. Would you elaborate?

R.W: There are certain things through heritage that are passed down to all of us. The drums were taken away from our ancestors because they were using them to try and break the chain of slavery. We took those same natural rhythms of Africa and put sounds into trumpets, trombones, piano, flutes, harmonicas, knives and forks, matchboxes, you name it. They were making string basses out of broom handles and rubber bands. All of these things are ingenious, and the African people created them.

When the slaves arrived, despite the conditions, they had to have music. When they came in contact with European music, they put their thing into it, and from that came all this beautiful music — the blues, gospel, jazz, Latin.

B.K.: In your travels through Africa, were you able to identify a specific region as being the link between African music and that of American origins?

R.W: No, but what we now have is fantastic. Because of what happened, those rhythms got mixed. People got together and produced some terrific musical offsprings. Our ancestors were separated through slavery, not able to converse with each other, so the people spoke the language of music, not the language of words.

B.K.: The music of the Caribbean is quite different from the North American derivation. What inhibited cultural assimilation between these two closely-linked regions? Outside of Brooklyn and a few other areas, Caribbean music hasn't taken-hold across America as jazz did.

R.W: That's an excellent question. I've never been asked that before. I don't know. Maybe there was a higher concentration of people in the larger cities. My dad is from Jamaica, and my mother is from Virginia, so I came in contact with both cultures.

B.K.: What's the historical role of the artist in African community life?

R.W: There's an underlying spiritual foundation which seems to be there throughout the continent; at least that's been my experience. The musician's role is that of a historian or storyteller who creates music for all activities and highly respected in the community. At the same time, they can reach the spirits and perform intense rituals. The top masters do all of these things. It's emotional, supernatural, and has a lot of magic. That spiritual foundation of being totally in tune with music regardless of where we are living is unique to us. No matter what form it is, we must have our music.

My mother and father could put on an Ellington record, a Basie record or a spiritual quartet. It was no big deal. They were multi-cultural within society. It was something nobody talked about; it was just very natural. We are people who are music. It's what the creator's given us; it's total.

Growing up in Brooklyn, the shoe-shine boy would be shining your shoes whistling Charlie Parker solos note for note. We talked about music for 24 hours a day. Who was the best — Coleman Hawkins or Lester Young? Or do you know what happened to so and so in Kansas City?; he fell and broke his leg. It went on all the time. I'm not talking as a musician; we were all fans of the music before we started to play.

B.K: Is there a shared spiritual link between jazz and the soul as there is between the soul and gospel music?

R.W: Mother Africa has extended her spirituality to North America, the Caribbean, and South America. All of these 'musics' are spiritual because when they are played right, whether it's Mahalia Jackson, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker or Billie Holiday, the audience is lifted spiritually.

When Dizzy Gillespie gets through playing a solo, and you look at the audience, their faces are lit up. They're smiling. I have this wonderful thing with my audiences just playing the music. The creator is a real musician, and I am just the messenger. When you have this total harmonic and rhythmic trip together with the audience, it's something unbelievable. Every time I play, it's more amazing than before. There's a whole spiritual ritual going on with people of all colours, all ages, all sizes, at total peace with each other.

B.K: As a jazz composer, you've written classics like Little Niles and Hi-Fly. Were you able to retain the copyrights?

R.W: Absolutely.

B.K.: You use the piano differently, playing the bass register like a tonal drum while using space in equal portions. Describe your style in further detail.

R.W: It's like the way I speak, the way I walk, the way I move. I guess it's a combination of all the influences in my life. When I play, you're going to hear Monk, Ellington, and Basie. You may not recognize Nat King Cole, but he's in there. You're going to hear Africa, the black church and myself altogether. I can't figure out what style it is. It's an identification. It's me.

B.K.: You've recorded five albums for Verve/Polygram — Portraits of Duke Ellington, Portraits of Thelonious Monk, Self-Portraits, The Spirits of Our Ancestors and Volcano Blues. Are you pleased with the critical acceptance of your music after almost 40 years of recording?

R.W: Yes. I'm blessed. I can never say anything unkind about the critics as they have been there for me all of my careers. My latest recording is Volcano Blues. It's all different kinds of blues. I've got Johnny Copeland singing two tunes.

B.K.: Is there any particular session that has a more substantial emotional or creative importance to you?

R.W.: There are three that come to mind. The African Cookbook featured Booker Ervin, Ray Copeland, Big Black, and the others. That was my most potent band Uhuru Africa, recorded in 1960, which was very important to me. I did it with a 23-piece orchestra, and Langston Hughes did the text. It's a work celebrating some of the African countries gaining their independence. Everybody is on it: Clark Terry, Max Roach, Gi Gi Gryce, Freddie Hubbard, Yusef Lateef, Ron Carter and George Duvivier.

And Little Niles with Melba Liston. That was our very first date.