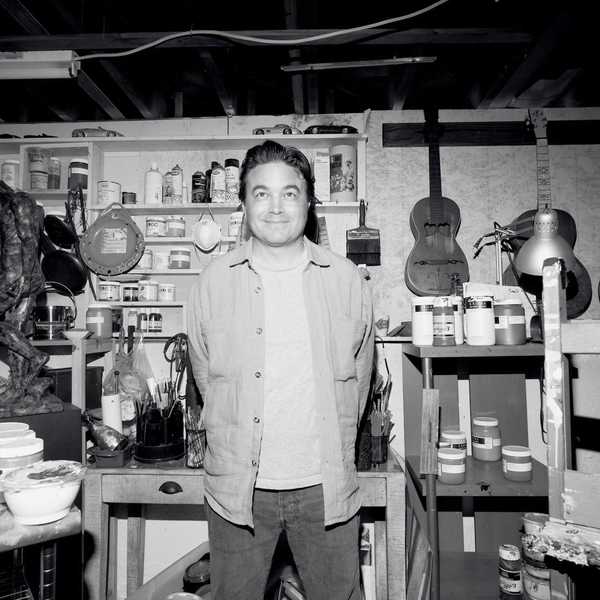

A Conversation With.. Harrison Kennedy

Harrison Kennedy was born March 9, 1942, in Hamilton, Ontario. It was a close-knit family of aunts and uncles, bootleggers and celebrity visitors that informed him of a grand world beyond. In the Detroit-based band The Chairmen of the Board he had a million-selling single.

By Bill King

I’ve known of singer/songwriter/musician Harrison Kennedy for some years. The late blues musician Mel Brown and Kennedy had that roots connection with the U.S. and cut their teeth on the blues and R&B.

The Underground Railroad played a significant role in the lives of their ancestors. And the sprint to freedom. For every celebrated white jazz musician like the late Moe Koffman, there were numerous black musicians of equal stature that played near the fringes of Canadian society. Although Canada was a forwarding thinking and compassionate country it offered little relief from low-pay and substandard living conditions.

To commemorate Black History Month, I thought a conversation with one of the country’s greatest assets and a truly magnificent artist was in line.

Harrison Kennedy was born March 9, 1942, in Hamilton, Ontario. It was a close-knit family of aunts and uncles, bootleggers and celebrity visitors that informed him of a grand world beyond. Kennedy. In the Detroit-based band The Chairmen of the Board he had a million-selling single “Give Me Just a Little More Time” and several follow-ups like “Pay the Piper” that sold over 500,000 copies. Then one day Kennedy packs it in and pursues a career outside of the music industry. After a 30-year lapse, he returns in 2003, then signs a recording deal in 2007 with Electro-Fi Records and has since released a number of acclaimed albums. Kennedy was awarded the 2016 Blues Album of the Year from the Junos. He’s also a multiple Maple Blues Awards recipient.

Have you always lived in the same region?

Yeah. Hamilton. I went to school here. It's been my home ever since I was a kid.

Where is your family from before that?

I was born and raised here in Hamilton. In the 1800’s my kinfolk walked about 2,000 miles to freedom. So, we've been here since the 1800s’ in Canada. My great great grandfather on my mother's side was a barrel maker, and they came here with First Nations people. They showed them the way to get into Canada.

‘Kennedy.’ What’s the background on the family name?

My father was Sicilian and black, and his grandfather was from Sicily. Giovanni Eric Angelo was his name, and he passed away when I was young. My mother remarried a Kennedy. So that's where the name came from.

We are both at a time to witness the birth of rock n roll. The early days of R&B and resurrection of the blues. Somehow that music found you in Hamilton.

There was always music in our house. We had visitors like Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, and Lonnie Johnson who came because we were bootleggers on the weekend. My uncle Jack [Jackie] Washington used to bring them over to the house. Jack had a thing for Dakota Stanton too.

I had no idea who these people were. I thought everybody played like that. We lived in a Jewish – Italian neighbourhood and you had to be resourceful. I even assembled my own steel wagon out of junkyard parts and would move through neighborhoods wheeling and dealing.

I liked the blues because I was exposed to it by my relatives from Tennessee and Detroit and down south when we used to visit when I was younger. My style is kind of like those who had little or no definable tradition, which I find closest to African structure, but organic just like jazz. Like Arthur Crudup or Tommy McClennan. Robert Pettaway, Tony Hollis who influenced John Lee Hooker. Skip James, Robert Williams from Louisiana. Bukka White was inspired by Charley Patton. Big Joe Williams. I think he played a nine string. Tommy Johnson. People like that. He was a rival of Patton’s. Tom Johnson wrote, “Canned Heat Blues” that influenced Howling Wolf.

Robert Peter Williams. That's the music that made such a deep impression on me. It was all about telling stories. And so that's where I was influenced and also by my uncle Jack Washington, who would come to our house and play and sing. It was all about telling stories, and that's what brought the people into it. I had influences from everywhere. When you're younger, the mind is a sponge. I always loved to sing at an early age.

I’ve heard most of the blues singers in Canada and in my opinion, few are as authentic as you.

There are no blues singers in Canada. In my opinion, there is not one. I can’t think of any. There are a lot of musicians I love and respect.

The blues was the church. I sang in the church. Not the kind of church you may think. Not gospel. It was more spiritual. Where you let go.

I used to go to my aunt's church in Detroit. And that was a different thing. And after we had church we'd go over to Aretha Franklin's church. I grew up with the Dixie Hummingbirds and groups like that. When you hear those kinds of things, they are fundamental, and they are related all the way back to the field. It was all about release and all about telling stories and if you told your story in the right way and even here in Hamilton at Reverend Johnson’s where I sang in a choir, and he would ask people to stand up and talk about what happened to them that week.

I just did a gig up in Owen Sound, and they weren’t sure if they liked the blues. I think maybe.

They'd hadn’t heard too much of the real stuff you know, maybe the ‘I shot my mother or shot my girlfriend, or I got drunk’ stuff. They see guys with a rip in their pants and that kind of shit is not the blues. I’ve got a lot more respect for it than that. I’m well educated, and I've always liked to write and put the stories down. That influence from family and from the people that were around me made such an impression on me.

I hear too much of what I fear is bar band blues. It’s not rooted in the names you rolled off above.

Honestly, it’s like I have relatives who played as well or better than these people that I just mentioned. They may have pointed me in that direction. But I had those who played the harmonica and sang and made up stories around me. It would just happen. It would be something that was happening, like just then and there, and everybody would understand what they were saying. It was fun.

You found yourself in Detroit in 74’?

I have relatives there. I was with The Chairmen of the Board.

What happened was I had Ron Scribner who was one of the top bookers in the area. The first time I played Toronto was with a blues friend of mine, and we put together a group called The Master Hand. I worked with them because I needed money to get into school. My university books were expensive, so I put this band together. We were playing, and a young lad was sitting out front about the same age who came up after and was excited. He introduced himself as Domenic Troiano and he said he didn’t play guitar at the time, but he was going to learn. He became friends with Russell Carter, my guitar player until the time when he passed away. That was the inspiration for him to play the guitar.

It was in Toronto where I got invited to try out for this group called the Stone Soul Children. Now Holland – Dozier - Holland had sued Motown, and they wanted ten million dollars. They tried to put a record label together, and they liked the girl who was singing with the Stone Soul Children to replace the main group, The Supremes. They asked me to go. I went for the ride and ended up accepting an offer to play with this group, The Chairmen of the Board. I had relatives down there who owned two Baskin Robbins stores. One of my cousins was an undercover police officer, but I never told anybody that. I kept that out of the conversation. I have a deep connection to Detroit and the United States even though I was brought up here. We used to take trips down there. I had no idea back in the day we were crossing the border. I just knew the longer I sat in the car people start talking funny.

Being with them there was an education for me honestly because they were serious people. They were business-like, and they wanted to succeed. It was very important how we carried ourselves on the stage and how we carried ourselves, off the stage. It was things like that which I respected and of course it paid off for them. Having all the hits with Holland-Dozier-Holland for so many years. I even covered a Beatles tune ‘Come Together,’ that they liked.

Did you get on well with General Johnson?

Oh yes. The idea was Edward Holland’s. He picked four individual artists that he felt, like he said to me, could go out and carry your show alone. He said that's very rare in the business when one individual can carry a whole one hour show by themselves. Each person in that band was able to do that.

He put us together as a group and highlighted each person. Me, I was kind of like the blues guy – rock guy. Danny Woods was soul. General Johnson had a unique sounding voice which was great for pop and then Eddie Custis could sing a robin out of a tree. He was more like a classically trained, you know, jazz singer. And he could do ballads and things like that. That was what they did. One of our tunes sold a million copies and the rest four to five hundred thousand copies. Probably double platinum. I don't know what the deal is right now.

Was it ‘Give Me Just a Little More Time?’

That was the big one.

We also wrote another tune called ‘Patches’, and I was responsible for that happening. I saw a fellow working in a field when it was 100 degrees. I said to General Johnson, look at that. I said he’s out there because he has to do it. General turned to me and said, ‘you're damn sure he does.’ He started writing ‘Patches’ in the car. By the time we got to the next gig we put it together with the band. We were using the Parliament Funkadelic and we went back to Detroit and told them we got a hit, a great follow-up for ‘Give Me Just One More Time’ and they said nope; too much country. So, someone else grabbed it and got a Grammy.

Clarence Carter?

Clarence Carter, yes. He copied General’s voice and sang it with all the nuances and everything. I think for me that was like the demise where I saw, well you know, they're not in it for the artistry. They’ve got a certain way they wanted to go, and they didn’t want to go off in another direction and I said, I don't want to be involved with this no more.

You played on Marvin Gaye’s classic recording, “What’s Going On?”

Let me put it this way. Not that tune, but I was there when they recorded that. You know there were many takes of that tune on that album. I played the harmonica on others. I used to play a lot, and they were always calling me up after that to play some harmonica for them. When I do the song live, I do a kind of like a folk version of ‘What's Going On’ because that's the one I like.

It must have been a fascinating session.

Honest to God it was amazing. The fellows were so good at what they did. And the energy, they would spend hours in the studio just running over one tune. Like for instance, when Eddie Holland wanted me to do an album he would call me, and I wasn’t living in Detroit. I lived in Windsor. He’d say, come on over and have a seat. I’d sit at the back in a chair against the wall, and these guys would do the work and Holland, Dozier and Holland would be working on those tunes. For two weeks I sat there for hours and then when it was over Eddie Holland would say, OK, Harry close the door when you leave.

And then he called me, and he says I want you to do an album. I said OK, what do you mean? I want you to do the kind of stuff that you like, Harrison; the other thing, you know. He knew that I was doing blues and that I was kind of like a folk singer. So, he asked me to put some tunes together like that. Well, that was a whole process. I had to find a band. I said, well I don't know how to play anything. He says, “what is it you like?” I said, “I like a guitar.” He reached into his pocket and brought out seventy-five bucks and says, “go buy one.” I got a second-hand guitar. I went to a secondhand shop. Now, I had to learn to play the damn thing.

While I’m in the studio, they walk in and basically cut right in the middle of one of my songs and say, “hurry up, hurry up, we’re here to write hits.” That was the kind of pressure that was there, which I like. I did the album, Hypnotic Music which was cool. They put a couple of tunes on it, and it was a learning thing for me. The business is not always pretty.

You remind me so much of Richie Havens. The two of you had a similar tonality about you. It was just that he was able to fall into that flower child movement, the hippie thing and be embraced by that because he stepped outside the soul thing. Havens cultivated a personality that was separate from everybody else.

Hendrix did the same thing. Like when my band used to open for him. He was a rhythm guitar player in the Isley Brothers. There was this guy in Buffalo I’d hang out with. When Hendrix went to England, the lead guitar player, Ernie Isley was already playing all of that psychedelic stuff in that band. Hendrix copped his style.

When I was with the Chairmen, Hendrix was so successful he had his own studio in New York City called the Cave. He hired some people to make this door look like a cave, and it extended halfway across the sidewalk. I don’t know how he got away with that, but he did. I went to visit him because we were playing at the Apollo Theater and thought I’d look up my old buddy and see if he was around. When I got to the Cave, the door was open. I walked down the hallway, and John Lennon is sitting there on a stool playing an acoustic song and singing. It was a fantastic song too. Yoko came out and said she didn't like it. So, he said OK, throw it in the can.

I was so upset man, it was all over my face and there was no way that I could hide it. I just turned around and kind of walked out. I mean, she comes over, “Oh John, Oh John, I don’t like it.” I went, 'Oh, my God, give me that song!'

*Negro History Week (1926)

The precursor to Black History Month was created in 1926 in the United States, when historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History announced the second week of February to be "Negro History Week." This week was chosen because it coincided with the birthday of Abraham Lincoln on February 12 and of Frederick Douglass on February 14, both of which dates black communities had celebrated together since the late 19th century

Black history in Canada

People of African descent have been a part of shaping Canada’s heritage and identity since the arrival of Mathieu Da Costa, a navigator and interpreter, whose presence in Canada dates back to the early 1600s.

The role of Blacks in Canada has not always been viewed as a key feature in Canada’s historic landscape. There is little mention that some of the Loyalists who came here after the American Revolution and settled in the Maritimes were Blacks, or of the many sacrifices made in wartime by Black Canadian soldiers, as far back as the War of 1812.

Few Canadians are aware of the fact that African people were once enslaved in the territory that is now Canada, or of how those who fought enslavement helped to lay the foundation of Canada’s diverse and inclusive society.

Black History Month is a time to learn more about these Canadian stories and the many other important contributions of Black Canadians to the settlement, growth and development of Canada, and about the diversity of Black communities in Canada and their importance to the history of this country.

In December 1995, the House of Commons officially recognized February as Black History Month in Canada following a motion introduced by the first Black Canadian woman elected to Parliament, the Honourable Jean Augustine. The motion was carried unanimously by the House of Commons.

In February 2008, Senator Donald Oliver, the first Black man appointed to the Senate, introduced the Motion to Recognize Contributions of Black Canadians and February as Black History Month. It received unanimous approval and was adopted on March 4, 2008. The adoption of this motion completed Canada’s parliamentary position on Black History Month.

*Government of Canada