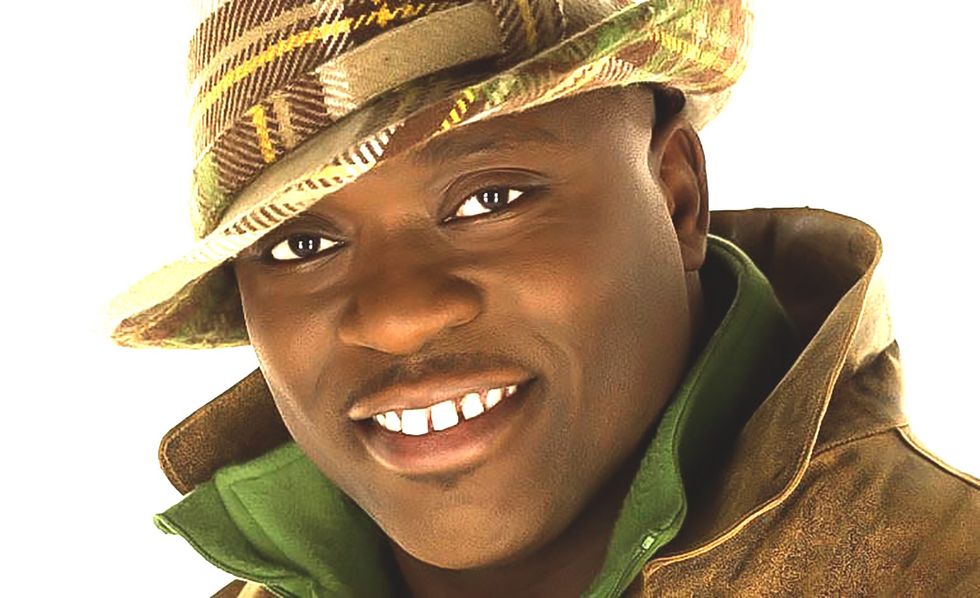

A Conversation With... Farley Flex

The ever-busy civic-minded music and sports entrepreneur talks about the growth of Toronto hip-hop, his love of basketball, and much more.

By Bill King

I’ve always admired the energy and passion Farley Flex brings to everything he commits to. We’ve sat across from each other on music juries, Juno committees, civic happenings, and it’s those intense conversations that focus on youth, basketball, music, and the GTA that most excite. I pinned Flex in place for a sit-down chat.

He's a Community Leader, Restaurateur, currently President and CEO of Plasma Management & Productions Inc., an integrated multimedia company specializing in managing the potential of people and projects in the entertainment and sports industries.

Farley is also the founder of R.E.A.L. School – Reality Education & Applied Life-skills, a not for profit organization focused on community capacity building as well as youth and community engagement. Flex has always chosen to juxtapose business endeavours with community contribution. His definition of self is Entertainment, Sports and People or ESP.

Having received multiple awards and recognition for his work in both areas, Flex was most recently inducted into the Scarborough Walk of Fame for his local and international contribution to the community, business and especially youth. Other notable recognitions include the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Award for his work with the world’s most vulnerable children, the Harry Jerome Award for Entertainment and Community Service, two Bob Marley Awards for Education and Community Development work and Business and Community Service, the Black Business and Professional Association Men of Excellence Award and several other awards and recognitions that speak to Flex’s ability to balance business with social responsibility.

In April 2016, Flex was presented with a Lifetime Honorary Membership from Toastmasters Canada.

Farley’s latest project is SAY IT LOUD.

SAY IT LOUD promotes Black pride through visual, performance, and culinary arts, technology, entrepreneurship, and social innovation. The initiative showcases Black youth, artists, founders, trailblazers and thought leaders challenging anti-Black stereotypes and leaving a positive impact on Black communities across Canada.

There will be competitions in Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Windsor, the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax. These regional events that showcase Black youth and their talent lead up to the first biennial SAY IT LOUD National Youth Summit in Ottawa during Black History Month in February 2021.

Bill King: You are one of the busiest humans on Earth. You’ve always got something going on that benefits those around you.

Farley Flex: That's kind of the way I was raised, man, by a mother who understands what it is to give. I remember being within earshot of the conversations she would have on the phone. My mom was a registered nurse and spent some time on the psychiatric side of things, so she was always consoling friends and stuff. But I've never heard her say to someone, no, I can't help you. As kids, that was instilled in us.

B.K: Did you come from Trinidad?

F.F: I was born in England. I was only there until I was about two years old, then went back to Trinidad and was there till I was about six and then in late October, came to Canada, and landed in Montreal. But we were living in Edmonton - I saw snow. Montreal snow and Edmonton in the same 48 hours and then moved to Toronto. I think I started grade two here.

B.K: What year was that?

F.F: I was born in ‘62 – probably age nine.

B.K: I’m guessing your relatives caught Toronto at a crossroads - I think it was in the mid-50s’ the government concocted a program (Until the “liberalization” of immigration policy in the early 1960s, Canada had racially discriminatory laws designed to prohibit non-whites from entering the country. To fill its post-war need for domestic labour in the 1950s, Canada began recruiting Black women from the Caribbean. The West Indian Domestic Scheme launched in 1955 and brought thousands of women from the region to Canada — in exchange for one year of service as domestic workers; these women were granted permanent residency and the eventual opportunity to send for other family members to join them in their new home.) The Establishment.

F.F: No, we were a little beyond that, and into the next phase of the Trudeau years.

B.K: What area of Toronto did the family settle in?

F.F: Actually, not too far from here at Christie Pits, on Crawford Street, and then moved to Scarborough; Markham and Ellesmere area for some time.

B.K: You attended school in Scarborough?

F.F: Absolutely. I went to junior public school and then a private school for a couple of years and then went to Lester B. Pearson, where I sowed as many wild oats as I could in terms of basketball and football - badminton, you name it, I played it. I was a reasonably good student as well. So, I was allowed to do a lot of different things.

B.K: You were following the trajectory of basketball becoming a primary sport in this city.

F.F: Tony Simms and Norman Clarke – guys like that.

B.K: Boxing – Clyde Gray …

F.F: Leo Rautins, of course…

B.K: Leo was a neighbourhood kid, and we all played together from the time he was 10 to 15 years old at Keele Street Public School. Every area of the city had a pocket where players congregated. What was yours?

F.F: L’Amoreaux in Scarborough. George Brown with Albert and those guys. George Brown was unique because all the school players would congregate there on weekends - train us, and we'd have scrimmages, and so forth. So everybody from “Bumsy” (Michael Morgan) to Norm. Mark and Paul Jones – Mark was younger my age, a year older than me.

B.K: Then came the Barretts – Jamal Magloire

F.F: I always believe, as Denham Jolly says quite eloquently, you got to know whose shoulders you're standing on. We would spot kids playing ball anywhere and give them some Raptors swag. That was a cool idea. It was to celebrate how basketball was now in the driveways and the parks like never before.

B.K: You and music?

F.F: Music for me was exposure through parents, an older brother, indeed in the home.

When we were young, and when we first came to Toronto, actually on Sundays, we'd have our home concerts. My older brother can play anything. He’s a bit of a phenom in that regard. He’s now got a wonderful son who's 15 and can play any sax - steel pan, guitar, you name it.

For me, I enjoyed singing a little bit - not a good singer. I enjoyed it when hip-hop started to evolve; I was freestyling with all the guys, stuff like that. Never on the recording side, but I always had this little business acumen bug kind of thing that was haunting me. But the real catalyst for me was when I did my first dance.

I think I just turned 16 and I did a breakdance competition, a place called Roller Palace. And I remember correctly at 10:00 a.m., I opened the front doors into the rink, and we had this breakdance competition. We had a regular dance because we wanted to make sure girls were there, and there were also people roller-skating around the perimeter. It was like a three-dimensional thing. I don't know how many crews we had, 30, 40, breakdance crews. I remember seeing the ethnicity, the diversity of the city. I said, 'this thing, just like my sporting life brings people together.' Sports and music were the two things that could bring harmony to this planet, man. I've always said that.

B.K: How did hip-hop take hold of the GTA?

F.F: So, to my humble recollection, I remember hanging out after school. I had the great advantage of a deejay named Tony Duncan from the Sunshine Sound Crew, who was probably the ‘crew.’ The guys on the west side will argue, and I get that. But when Sunshine was throwing, other guys would reconsider their thing. And Tony was the kind of deejay who was also supported by his parents in terms of his musical interests. I remember when Phil Collins came out with In The Air Tonight that broke in the black community in Toronto. People don't know that. He would play that at the L’Amoreaux dances. It was the Leacock dance in particular I remember - Stephen Leacock at Birchmount and Sheppard, and all you hear is “putta poomp - putta poomp doom.” People are jamming the funk and mixing it with other funk. It was amazing. Songs like Shout, Shout, those songs - even broke Jack and Diane, all those songs. Tony got them early - his mum would go to New York a lot, and she would hear something - buy the record and bring it back for Tony. There was no other way to hear that before it hit the radio.

Funk music, as the predecessor to hip-hop, evolved, and guys like Tony were playing Fat Back and Jimmy Spicer and, you know, Spoony G - a lot of the young cats now may not even know their names, but these guys were the introduction. And then obviously the Houdinis came out as well. But it integrated into the social side of things, and it represented the jargon and the language of the street, literally.

We talk now about the various slang terms like the SIX and T. Dot, but Toronto always had, and Scarborough, in particular, always had that “scar bro twang” almost like being in a different community from the rest of the city. I remember some of those terms.

B.K: Give us an example.

F.F: The way you might say and because of the Caribbean, the multi Caribbean integration, - Jamaica has always been the dominant culture - but then you have ‘Trinis’ like me, who were more outgoing that would twist that stuff up and come up with a new word. Like, let’s “splurt” means to leave.

B.K: It’s much like on the streets of Harlem in the ‘30s and African-Americans coming from down south and the new blend of dialogue. People who were smoking weed were called “vipers.”

F.F: Assimilation came out of that integration, especially in the black areas. I grew up in Malvern, so Malvern was technically somewhat geographically isolated in its own little way. I remember when I went to Lester B. Pearson, we were there for the first year and the school wasn't ready in September, so we had to travel to Albert Campbell at McCowan and Finch and use the school from 8:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Then the Campbell kids came from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. or whatever 6 p.m. They would split the school with us for the first couple of months, and then we moved into Pearson, I think, in November. But we were commuting. We had tons of fun stuff that we did, but the music was always part of that - all the dances, break dancing. You know, even before the big dance, because when I think about it, for all of the kids, ‘big dance’ ways still younger than me at that time. You're carefree at that age, too.

B.K: What is the story of Scarborough today? The hip-hop, rap, the reggae…

F.F: In many ways, it goes back to the Maestro.

Maestro Fresh Wes and I met actually at a roadhouse restaurant called The Wizards at Kennedy Rd. and Sheppard Avenue. He was already part of a crew called Ebony MC, and Melody M.C. was the tandem, and they had done battles against people like Cash Money and Marvelous and all these guys at Ron Nelson’s parties. There was that fine line geographically between Scarborough and North York. So like V.P. Ron Nelson lived in the V.P. and Finch area, and technically, he was on the North York side of the city. There was no barrier. Wes spent a lot of time working with Stanley McClurkin in Fleming Park, which is also technically North York. But again, a couple of bus stops past Scarborough kind of thing.

I was coming home from university at the time at the University South Florida and when I came home, my late younger brother, rest his soul, was working at this Wizards restaurant, and I got a part-time job as a doorman there, bouncer type thing, and we'd have these freestyle battles. So, the freestyle battles would be the bus staff against the door staff. We’d come up with these lines, go back, drop the line, laugh, or whatever. They'd come back out. And we were crushing them - I gotta be honest. Then one miraculous day, they just transformed into “amazingness.” I said to my brother, what's happening here? How did you guys get so good so fast? Wes's future deejay, LTD and his younger brother also worked there - Paul Swaby - takes me into the back into the kitchen, and there’s this skinny kid with his back to the door washing chicken wings. They point out, and I said hey, “You're the one who is helping these guys up their game kind of vibe,” and he turns around coy and humble as he is and smiled. And that was the first time I met Wesley Williams.

I have to say, and I always want to make sure I mean - the kid's a visionary. He knew what he wanted to look like - he knew his name was going to be Maestro Fresh Wes. Hard to say for some people, but not hard to look at because he wore this tuxedo. He had a baton - conductor's baton. He had all that planned. His dad was instrumental too - the first picture you see on the Sympathy in Effect album - his dad took that picture in his house.

When I think about people like Kanye West and the difficult times he's had convincing people that he's an artist holistically - he writes lyrics, he creates beats, et cetera. He also knows what clothes should look like and what the art pieces in his home and stuff like artistry have no boundary. I love that.

B.K: FLOW 93.5?

F.F: That took 12 years to get off the ground. With FLOW, Denham Jolly always said that there's a social imperative and a fiduciary imperative. You've got to stay in business to be in business. So, there was always that balancing act between the community wanting a voice where they could hear the dialogue. But there was also the argument, business argument that we need people to listen. So that's where the music comes in. We had a talk show, Kenny Robinson, Gemini, and Maestro on in the morning, yet we needed to up our morning show game to be competitive in the marketplace to get the Molson’s and the big advertisers on board as an independent.

So we modified things in that regard.

I remember the effort, and I remember being at the CRTC hearings and the third time, which was a successful attempt and Commissioner Wiley saying to me over her glasses, “Mr. Flex, is there enough black music to run a 24 hour, seven days a week station?”

I remember this amazing moment, and I haven't shared this story with a ton of people, but I brought with me that day the history of black music. It was like it's the size of the old school, your grandma's Bible, the big one. When she asked the question without having a clue who was behind me or what was going on, I looked back, and there was a middle-aged black woman behind me, and I said, “mam, can I borrow your Bible?” I didn't know who she was. She handed me the little motel version of the Gideon one. I said,” Madam Commissioner, I have here, in my right hand The Holy Bible, the King James version and in my left hand and I picked up the big one, I have the Bible of black music, the King James Brown version.” I never forget that. That was the primary sort of moment for the successful hearing.

It was cool. And, you know, all Denham and the finance guys had to do was show, you know, the marketing - this that the other. But. But I was the music guy and talked about how prominent the music was, and I thanked the commission in my opening statement.

We look at all the unfortunate things that are happening in the streets now in terms of gun violence, and there is still no platform with a real sense of media influence. I'm happy to say there are some more national organizational strategies - I don't know if you're aware, but I try to make folks aware we're currently in the middle of what the U.N. declared the decade of people of African descent. It got announced by our prime minister five years into its life. So, it's halfway done. There's a lobbying effort to extend that, to the full ten years in terms of recognition, because, you know, like our indigenous brothers and sisters, we have to ensure that we are inclusive, deaf people throughout – and that diversity and inclusion are important words. And we have to recognize that when we don't address them, there's going to be fallouts - serious fallouts. Bodies are dropping, and it's regrettable, and there's a lot of history to that, of course.

B.K: From when FLOW came on the air to now, the lyrics are mostly explicit and can’t be played on mainstream radio.

F.F: To a point. Young people get the music at the touch of a fingertip on their mobile phones from whatever source they want. Radio now facilitates an element of validation that the mainstream is aware you exist. That's still an accomplishment. It's almost like if you're a YouTube star, and when you get the call from Jimmy Fallon or Ellen DeGeneres, you still feel, Yeah, I made it. You could have 10 million followers on YouTube but getting on TV is number one. The same thing with the radio. When you are a local artist, and you're getting like one point two million views on your videos, et cetera, et cetera when you get that call from the FLOWs or maybe even Virgin or whomever - that validates what you've been doing.

B.K: Even with greater choice, terrestrial radio is still a powerful medium.

F.F: Two different worlds. And there's so much success happening in the free world. Those young artists don't care, quite frankly, about getting on the radio. They don't need it. They're touring. They're making money. They're doing “collabos” – there are meeting other people who live in the free world side who say, “let's do a track together,” and now you've got young kids from all the neighbourhoods who are making tracks with Chance the Rapper and this guy and that guy, and there’s no barrier. And that's the difference.

I love the radio. I love all kinds – ‘talk radio’ - just radio in general. But the young people I run into are kids who don't know what FLOW is. I was at a community initiative yesterday, and there was a couple of kids, 14, 15, 16-year-old they have no idea what FLOW is. I said my intro, “how many of you know FLOW 93.5? I’m one of the people that founded the station,” and they look at me with a blank stare, but they know what YouTube is. It's the democratization of it all.

B.K: It’s still about the song.

F.F: Working with a guy like Wes who in the years we worked together - uses the English language and melts it down, shapes it, sculpts it, puts shellac on it, and then offers it. I tell people this all the time, Let Your Backbone Slide - his biggest song - people say, Farley, “what's a hit?” “What's the end game?” You can look at a hit from an anatomical standpoint, what's the anatomy of a hit? And when you have a song, you're performing it in front of an audience, and a different person has a different favourite line in your song, like 15 different people, so you see them screaming, that’s it.

There are certain parts of a song, like I said, the anatomy of a song and whether that's Ed Sheeran or Maestro Fresh Wes or when Ed Sheeran says, “Our Love Will Never Grow Old It’s Evergreen” or “When your legs don't work like they used to before, and I still sweep you off your feet?” That stuff is good. That's why the guy made eight hundred million dollars on tour. Not because the people like red hair and he looks quirky or whatever. He stands there and that’s his production. It’s him and his lyrics and the backing track.

B.K: You are so connected to your community, which is always in flux – what message do you give the kids adapting to a changing world around them?

F.F: There's no 100 percent foolproof way, but there's a certain amount of information and love that you can impart to a young person that makes them resilient, and resiliency comes with the ability to make choices, the right choices.

My children grew up in hip-hop. Their dad is a hip-hop guy, but hip hop doesn't impact their psyche like somebody who didn't have a dad like mine. That's the resilience I'm talking about. So when we're listening to a song, if it has profanity or it has some derogatory miscegenation, we ensure that as a parent, coming up, they understand where this comes from. Hip-hop, as beautiful and as much as I love it, is an oppressed culture. It comes from an oppressed culture. The content is a manifestation of the trauma that the creators have inter-generationally inherited. That's the part we got to appreciate and no different from our indigenous brothers and sisters. There’s nothing wrong with black and indigenous culture - but there's a lot wrong with what colonization did to both groups. Just like our Somali brothers and sisters who are, quote-unquote, spreading out in the city, are coming from war-torn circumstances. So their value for life is twisted. If you can't value yourself, you don't want to be the person coming down the sidewalk on the other end, because that person that's approaching you or your approaching may have a diminished value that the system has placed upon them. It's not inherent in their thinking. They inherited it right from the system, from teachers.

Bill, I was in grade eleven. I'm a math fiend. I love mathematics and the objectivity of math. I walked into my grade eleven ‘relations and function’ class and the teacher says something to a kid named Darryl Sampson – who played for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers for about 12 years and me. Darryl, was a straight B student, as was I. And the teacher says, “if you two think you're going to get a passing grade in my class because your athletes, you've got another thing coming.” This is the introduction we got on the first day of school. That’s blatant racism. My confidence and Darryl's confidence in our abilities to do well in the class got us past that stuff!