Chester Thompson - From Jazz to Genesis

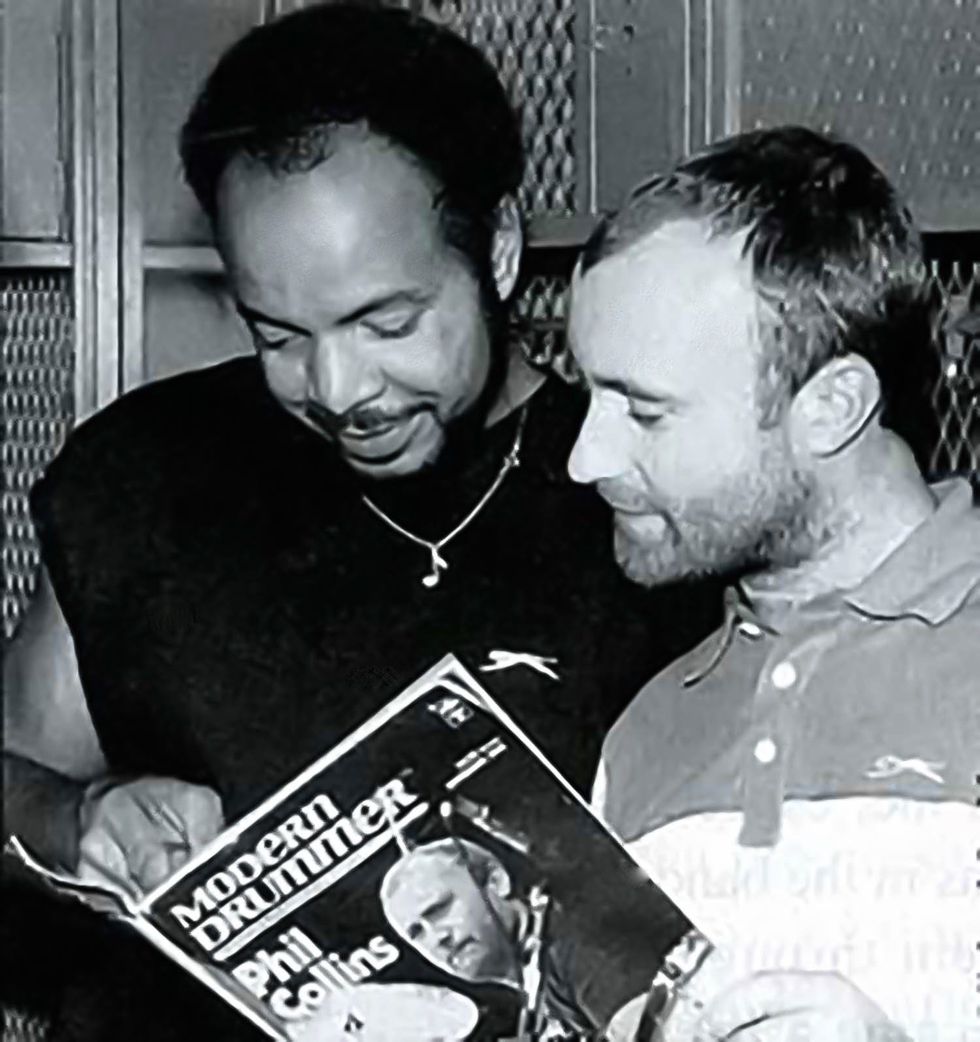

The masterful American drummer has shone in a wide array of settings, from Frank Zappa to Weather Report to the Pointer Sisters to Genesis with Phil Collins (pictured). Learn more of his fascinating career in this interview from the archives of a former bandmate.

By Bill King

Its been 42 years since drummer Chester Thompson, bassist Jeff Breeh, and myself were the backing/touring piano jazz trio for the Pointer Sisters. Getting the gig was no walk in the park. Producer David Rubinson was conducting auditions and players were entering and exiting quicker than ticketholders at a Lauryn Hill concert.

Rubinson played the jazz card.

Music director Sandy Shire took a liking to me and lent me the charts a few days in advance of auditions. I practiced along with the recordings. When my chance arrived, I walked away with the keyboard chair. Bass situation was already resolved. Now it’s down to who will be smacking the drums.

An array of elite Hollywood drummers entered and left as quick. All was cool until Rubinson called Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts” and set the tempo at Charlie Parker be-bop tempo.

“I’m calling the tempo and if you can’t keep up, leave," says Rubinson. Brutal! Only one survived the grind, drummer Chester Thompson. Chester not only survived, but he also rewrote the charts as he went through the supposed audition. Jeff and I looked back at each other and prayed this would be the guy. Chester was our guy, and the gig was on.

Over the next few months we toured, we hung out, shopped and talked nothing but music.

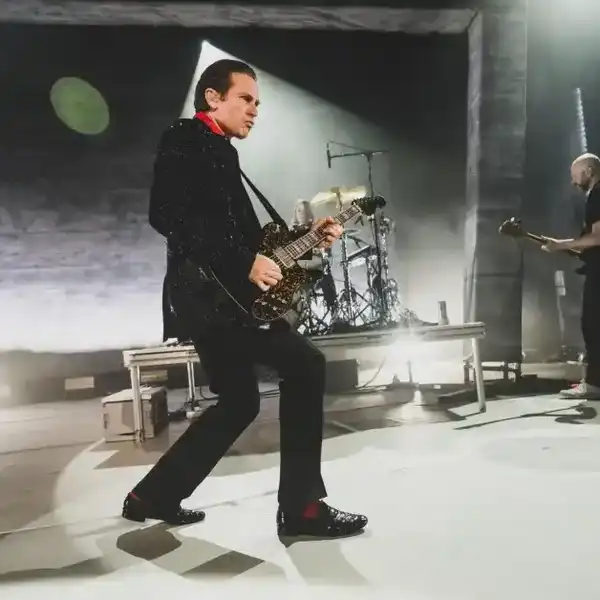

Chester was a member of Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, Weather Report, the Broadway show, The Wiz, Genesis, Santana and a decade or so back, The Bee Gees.

I recently came across an interview Chester granted dating back thirty years. This is special. Catching a player in his prime and in action with the greatest bands of the day and picking their brain gives the best insights. Enjoy.

Bill King: Are you currently between tours?

Chester Thompson: As far as Genesis goes, we're still on a long break. I don't go back out with them for a while, but Phil Collins is doing a solo tour next year. Lately, I've been trying to do my own music.

Are you laying tracks down in a studio?

I've been doing what I call "The L.A. Hustle," doing demos and playing some gigs. I put a band together, and we've been having a pretty good time.

Does your band lean toward fusion?

It's a mixture. We do several instrumentals which are in a fusion style. My wife, Ros, and I are doing material that we write. I guess you call it pop, but we try to make the rhythm end interesting. I like songs with good chord changes.

Who is in your band?

The guitarist is Bud Nuonis; he used to be in a band called Seawind. The bass player is Pee Wee Hill. His wife, Michiko, and Mark Gazberra are the keyboard players, and my wife is doing the vocals. Pee Wee and Michiko have worked on my projects over the last 10 years — whether it was writing or forming bands in the L.A. area.

Did you grow up around Los Angeles?

No, I grew up in Baltimore and began playing gigs around the age of 13. I played in the local bars and clubs. It was a healthy playing environment with at least three jam sessions a week. I was able to learn all the standards and play a lot of bebop while I was growing up. I guess I played my first jazz gig when l was about 14.

Was your family involved in music?

Not really, my oldest brother enjoyed playing, but he never pursued it past the drum corps stage. There was a real close family friend who was a jazz drummer. He made the mistake of telling me I could come over to his house whenever I wanted, and that turned out to be almost every morning. We'd sit down with a bunch of albums, and he'd teach me how to play along with Miles and Cannonball. Then, I discovered my most significant influence — Elvin Jones.

Was this your introduction to music?

In elementary school, we had these little plastic flutes which had a number system for playing instead of notes. This bothered me. I asked my sixth-grade teacher if she could teach me to read music because I didn’t want to do this number business, and she conceded to teach me to read the basics.

By the time I got to junior high, where I had my first drum lessons, I could already read basic patterns. While there, I did a lot of really extensive rudimental drumming. There was an organization of rudimental drummers at the time called NARD. They had a book of solos, so I proceeded to learn as much of that material as I could. As I got older, I tried to seek out more unusual situations to play in. I’m always looking for something new to play. I’m not a purist, in the sense of playing just one style of music.

You’ve worked with both Weather Report and Frank Zappa where there is extensive reading and memorizing involved. Did this training enhance your development?

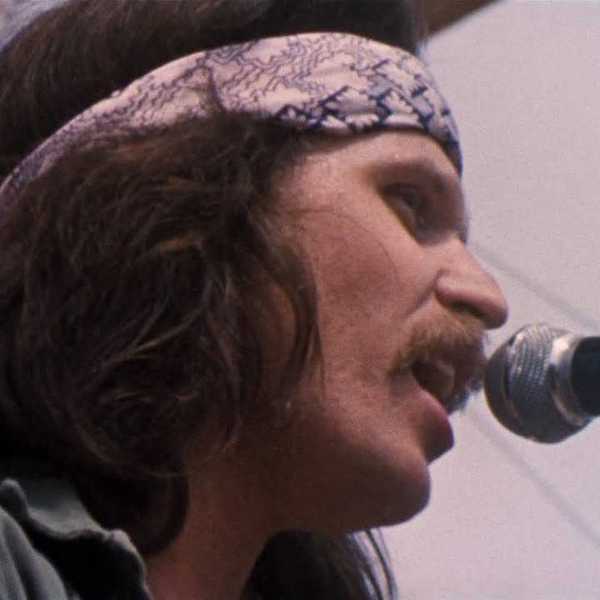

The Zappa band was like going to graduate school. I was in the 1973-75 band. It was with George Duke on keyboards, Ruth Underwood on synthesizers, Tom Fowler on bass and Bruce Fowler on trombone. That was the core of the band. Napoleon Brock was singing. A few people changed around that nucleus.

Were there recordings?

The first one I did was Roxy, with Ralph Humphries and myself on drums. Another was One Size Fits All, and I did most of the one called Studio Tan. I didn’t get credit on that because part of it was me and the rest was Terry Bozzio. Those were the main recordings I did with Zappa. I stayed with him for two years, then I went straight into Weather Report and did the album, Black Market.

How did Zawinul and Zappa contrast as leaders?

They’re both intense; maybe it has something to do with both names beginning with Z.

Were they demanding?

Yes, but not unreasonably so. They were both very clear on what they wanted. When I look back on it, playing in Zappa’s band taught me how to play all kinds of notes. Then, in Weather Report, I learned what to leave out.

Who were some of the earlier artists you backed up?

The first “name” gig I had was with Ben E. King, but my first steady band engagement was with organist Jack McDuff. That was around 1970, and that was a real education, too. I had to learn how to swing and push a band with basically, a ride cymbal and a high-hat.

What was the lineup?

He always had a least two horns, a guitar, and then he’d go all day on the organ.

Were you comfortable working with organ bass?

Man, growing up in Baltimore, it was a real rarity to play with a bass player. Most of my early gigs, especially the jazz stuff, was with organ bass. There were a lot of excellent organists in town. They played good changes and knew plenty of standards. I played my share of "Cherokee. "That was blown at every jam session. There were always about four horn players, each wanting to play about twenty choruses, so my endurance developed quickly.

Organ duos and trios were a hot commodity during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

In Baltimore, it was more common to hear an organ trio. For some reason, the organ trio became standard instrumentation.

Do you think Jimmy Smith had much to do with that?

Oh yeah! You know the early Wes Montgomery recordings with Mel Ryne on the organ? Well, we made a lot of those arrangements.

Mel’s innovative playing was captured on those Riverside recordings. He was one of the most influential organists of that time, yet, he is rarely mentioned.

I never did get to see him live.

Are you playing much jazz these days?

I find myself doing different rehearsal big bands and various bebop gigs on the west coast. Obviously, in L.A., it's not an ongoing thing; you've got to seek it out. Fortunately, something always comes along before things go too nuts and I get to flush the old ears out with some bebop. That kind of puts it in perspective for me.

There might be more bebop out there after Eastwood's movie Bird comes out.

Yeah, I hope so. Instrumental music does pretty well out here. For the size of the city, there doesn't seem to be a lot, but something is always going on. Dance music is popular here, but even early jazz started out as dance music of the day. They danced to the cymbal ride. After a while, improvisation became the essence of jazz, and I don't think we're getting any less of that these days.

A lot of guys have to please the record company, but that kind of stuff will always go on. I think there's a good number of guys playing some honest, straight from the heart material. I could use a lot more, but I think it's a very healthy time. You've got guys out of New York, like the Breckers, who continually put out some very happening music. I think there's a hunger for creating something a little more substantial these days.

Do you sense a division between youth and adult listening preferences?

If you look at who controls the media and commercials these days, it's the baby boomers. Every other commercial reflects something out of the '60s or '70s. These people have made their way into positions of management and, now, they're having their say.

I don't think it's an accident that suddenly jazz seems to be more popular, and I don't think we've seen its popularity peak yet. There are many people who put in long hours and, at the end of the day, they want to hear something more than Muzak or a drum machine thumping away.

Was The Wiz the first big production show you were involved in?

I'd never really done a serious show like that before. I had done some small theatre projects in Baltimore, but this was the first time I had to play the book of a serious musical, where the charts had been written and arranged at that level. Harold Wheeler did them. He does a lot of New York musicals. He arranged some of Grady Tate's solo albums and is a very tasty jazz arranger. He wrote the book for The Wiz and, man, that was a drummer's dream. You could really get your teeth into it.

A friend of mine, Roy McCurdy, recommended me for it. The conductor knew Roy from New York and tried to get him to do it while he was out there, but Roy was already busy on the road. He passed it on to me. I ended up having to wait a while before doing it because I was still a member of the musician's union in Baltimore. It was one of those weird situations where someone thought they had secured the gig because they were doing rehearsals, and, believe it or not; they called the union complaining that I was being offered a job and didn't think I was a member of the local. The union had to follow this up. Regardless, I decided that New York was going to be home, so I went ahead and transferred unions. As it turned out, the chance of doing the show came around again, and it worked out very well. Not only was the show great, but this was where I met my wife. She was playing a couple of parts in the play.

Didn't you almost join Santana during this period?

That didn’t materialize until 1984, but in ’76 I did some rehearsing with him, and he wanted me to join the band, but it didn’t work out. Some business things didn’t make sense to me. Fortunately, they didn’t, because two weeks after that I ended up getting the Genesis gig.

How did this come about?

Phil was particularly interested in a two-drummer combination so that he could sing out front. He had seen the last Weather Report concert I did, along with hearing some of my work with Zappa.

I was in San Francisco doing The Wiz, staying at Bill Allen's house - he's a mutual friend. Phil called and said, "I know who you are, and I've heard you play. Would you be interested in a gig?"

My thing has always been, the more variety something has, the more I've got to check it out. I liked what they were doing composition-wise. A lot of the songs were in movements, really sensitive tempo changes a very interesting situation. I thought I’d give it a try. Little did I know I'd still be with them 11 years later. It's worked out beautifully.

Right now, we're not on tour, so I'm finally able to sit down and try to complete some of my projects. I usually end up making some headway, just in time to look up and go out again. When I come back, it's like starting over again because everybody else has had to find other things to do while I was away.

Did you work out the material with Phil Collins, separately?

No, we just jumped right into rehearsals. In those days it was a two-and-a-half-hour show and having not done that before, they scheduled 10 days of rehearsals. Halfway through they decided to take a day off because they thought it was going well. They didn't realize I was staying up to four and five o'clock in the morning writing out charts because they didn't have any.' I’d sit and listen to their records and make my own charts. It was a nightmare trying to learn all that stuff in such a short time. Now, we rehearse for a month before every tour.

The first two weeks are spent learning the music, and the next two are spent in the production areas, lights and sound. We do extensive production. On the last tour, we took six 48-footers full of gear. They give it their best shot every time out — which is really nice.