Unnecessary Middleperson Syndrome: The Story of Neighbouring Rights Royalties in Canada (Guest Column)

What began as an attempt to figure out why my record label's royalties were decreasing turned into an eye-opening education about the extent to which neighbouring rights royalty collection – like so many other aspects of the business – is broken.

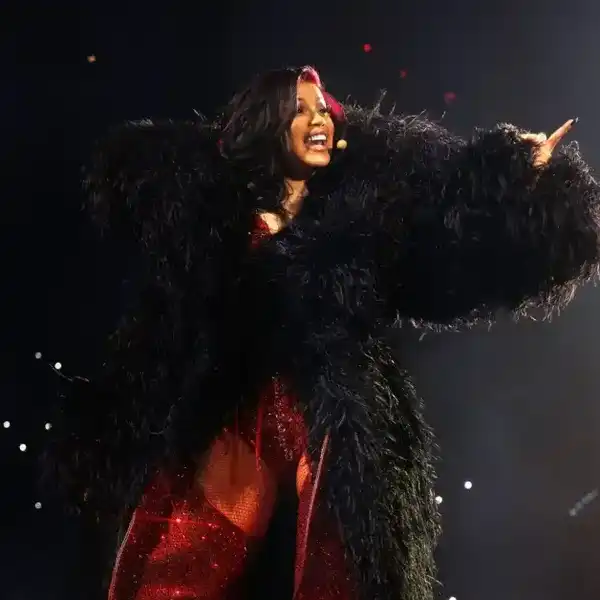

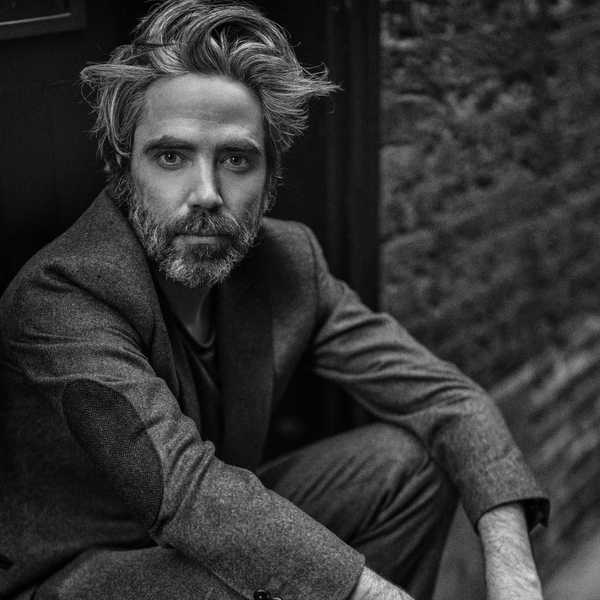

Jonathan Simkin, president and co-founder of 604 Records

The music business in Canada is infected. It’s rife with conflicts of interest, self-dealing, major label greed, and – most aggravatingly – a virus I call Unnecessary Middleperson Syndrome (“UMS”).

UMS refers to entities in the music industry getting paid for no valid reason, simply because they are in a position to do so.

Recently, I came face to face with this rampant syndrome while looking into discrepancies on royalty statements of 604 Records, the independent label based in Vancouver which I founded in 2001/2002 with Chad Kroeger of Nickelback.

What began as an attempt to figure out why a significant chunk of our neighbouring rights royalties appeared to go missing turned into an eye-opening education about the extent to which the neighbouring rights royalty collection system in Canada – like so many other aspects of the business – is broken.

But let's start at the beginning.

I fell into the music business by accident.

In the early ‘90s, I was a poverty lawyer plying my trade on the bleak streets of Vancouver’s Downtown East Side. I was a necessary middleperson. Without me, the refugees and criminally accused I represented had little chance of avoiding deportation or criminal sanction. When I started in the music business, it was as a lawyer. I was a necessary middleperson in that context also, protecting artists from the worst of the business – often with major labels on the other side of the table. I was paid for my services, and I delivered value in exchange.

Now, as president and a co-founder of 604 Records, I am part of an industry where unnecessary middlepersons are rampant.

My introductory direct experience with UMS came when we negotiated our first distribution deal. I talked to every major label, and 604 ended up with Universal Music. As part of that deal, 604 retained digital rights over our masters. The major labels and others in the industry told me that this was not “standard,” that all indie labels give up digital rights to their distributor. But this explanation made no sense to us. Why pay a third party to do something we could do ourselves? It takes zero skill to upload songs to the download store. Why would we pay someone to do that for us? Needless to say, not taking the “standard” route worked out great for us in that instance.

When 604 started, I asked more experienced people how we should deal with neighbouring rights. In a nutshell, neighbouring rights royalties are public performance royalties payable to both copyright holders and artists whose recorded performances are embodied on a specific recording. Distinguished from compositional royalties that flow to writers and publishers, neighbouring rights royalties are generated when a sound recording is publicly performed or broadcast (i.e. not sold) on radio, television, on certain digital streaming platforms or at public venues like restaurants or clubs. Typically, the recipients are artists and record labels.

In Canada, the label share of neighbouring rights are collected by dedicated companies. When we started 604, the near-unanimous advice we got – including from our major label distributor – was to sign up with the Audiovisual Licensing Agency (“AVLA”). If there were other options, I was not aware of them. All the labels seemed to be with AVLA, so in 2002 that’s where we went. AVLA subsequently changed its name to CONNECT Music Licensing.

So…what is CONNECT? Put simply, it’s a music licensing agency operated as a federal corporation, with the three major labels (Sony Music Canada, Universal Music Canada and Warner Music Canada) as its three shareholders. Until the end of 2024, CIMA (the Canadian Independent Music Association) was also a minority stakeholder.

Theoretically, CONNECT distributes master recording royalties arising from public performances including neighbouring rights royalties, licensing revenue, DJ pools, etc. 604 is lucky to own a number of recordings and music videos that receive substantial public performance, such as “Call Me Maybe” by Carly Rae Jepsen – at one time the most performed song in SOCAN history and still in the top 5, some 12 years after release.

As the success of the label grew, so too did our payments from CONNECT. It became a significant source of revenue for 604. It was a reliable, consistent revenue stream, and since it was working, we stupidly didn’t pay much attention to it. We entrusted the collection of these royalties to CONNECT, and trusted that they were doing their job for us diligently and competently.

Another big player in the neighbouring rights world is Re:Sound. Re:Sound is a not-for-profit music licensing company responsible for licensing businesses to use music and for collection and distribution of royalties on behalf of all label and performer collectives. Re:Sound collects huge amounts of data, most notably logs from music users, and imports them into their data system. It then analyzes the data to ascertain which public performances earn royalties. That information is then passed along to organizations that collect and distribute the royalties, such as CONNECT and the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists (ACTRA). ACTRA distributes to performers.

Our relationship with CONNECT was simpatico for the first 15 years. That changed in 2020/2021. CONNECT informed its members that Re:Sound was implementing a new distribution system, which it switched to in 2022. It would be a “seamless transition,” they said, but some temporary delays in the payment of royalties were possible. CONNECT even offered advances to its members who might be negatively affected by a delay in payments.

Thus began a dark and increasingly hostile phase of our relationship with CONNECT. We noticed that our revenues were dropping. First it was a small decline, then a nosedive. Over a five-year period from 2017 to 2022, our revenues fell by approximately 90%. It was distressing.

I’ve never been shy about voicing concerns, so I started to ask questions. I went right to the top executives of CONNECT to try to get some answers. And boy, did I ever get some answers! The problem is, the answers I received at the time were constantly changing and seemed borderline bizarre at times. They included:

- The tariffs established by the Copyright Board of Canada had decreased.

- The radio reproduction tariff payout, a significant revenue stream, covered five years at once in 2017 after a settlement reached with broadcasters and certified by the Copyright Board.

- The 604 catalogue was not performing well.

- Re:Sound’s distribution system was still being brought online, had a number of problems, and the software upgrade might take years.

- COVID’s effect on offices, retail establishments and concert venues and thus commercial performance revenue (Based on 604’s revenues, it seemed like people were listening to music more than ever during the pandemic).

- The war in Ukraine (No, not kidding).

- 604 had not properly registered our catalogue (utterly untrue)

We were bombarded with myriad excuses, yet there was no clear or compelling explanation for our plummeting and missing royalty payments, as reflected in our CONNECT statements.

Then, we found a smoking gun. As we were reviewing our CONNECT statements for 2021, we saw a surprising lack of revenue for two songs by 604 artist Coleman Hell: “2 Heads” and “Fireproof.” Both were significant hits in Canada and internationally, but according to CONNECT, neither song had earned a single cent in revenue. The songs had peaked a number of years before, sure, but the suggestion that neither received any airplay was ridiculous.

Like a pit bull, biting down until I got an answer, I found the cause: royalties for “Fireproof” had been mistakenly paid to Sony Music Canada.

I’m not blaming Sony. They promptly made this right with us after we contacted them, and it should not be the obligation of parties receiving statements to spend time and resources reviewing them to make sure they didn’t receive somebody else’s money. But we are not talking about a small amount of money. We are talking about $65K, give or take, on just that one mistake. But, as a major label, Sony is one of the primary shareholders of CONNECT, and it has a representative on the board of both CONNECT and Re:Sound. The optics: not great. And this was not the only 604 repertoire whose payments went to a major label. If this was happening to 604, it is reasonable to assume that it was happening to other labels as well.

Here’s the thing: what if we hadn’t made a stink and hadn’t insisted on getting answers that made sense? What if we accepted the excuses given by CONNECT? We would never have recovered that money. And why did CONNECT gaslight us, rather than help us find this money?

When we saw how casually such a mistake was made and how little concern there seemed to be about correcting that error, we dug in deeper on the data. The more we dug in, the uglier it got. The extent to which there were irregularities in our accounting statements was alarming, including more payments made to the wrong party on artists such as Ralph, Theory of A Deadman and Dani and Lizzy. At that point, I started to look for other options for neighbouring rights representation. I had to pull 604 off of the Titanic before it hit the iceberg.

SOPROQ is a Quebec-based not-for-profit collective rights management organization that represents rights owners. We left CONNECT and went to SOPROQ about 18 months ago. We explained our urgent concerns, and SOPROQ has done an amazing job of going backward in time to collect as much missing revenue as possible. The amount of revenue that SOPROQ has recovered that should have been collected and paid during our time at CONNECT is eye-opening. Hundreds of thousands of dollars. And they are still finding more!

Funny thing is, SOPROQ was always an option for us – we just didn’t know it! I have been wondering why that is. I do not personally know of a single indie label in English Canada who was with SOPROQ between 2001 and 2020. Was this just a cultural phenomenon? Quebec labels went with SOPROQ, and labels outside of Quebec went with CONNECT? I think that is part of the explanation, but it is also clear that the majors pushed the labels they distributed towards CONNECT. That is certainly where Universal directed us.

604 was lucky. We made the move early, which made it easier for SOPROQ to collect those royalties for us. With each passing day, it becomes harder to collect from the past. My understanding is that some indies may never be able to recover all lost revenues.

So…where did our money go? It seems to have disappeared for a number of reasons:

- Payments were made to the wrong party (as per the “Fireproof” mistake).

- Payments were held because there were conflicting claims about master ownership (these conflicts were not brought to our attention, so we did not know money was held back!). This is apparently what happened with “2 Heads.” Connect tried to blame us for improperly registering our rights which was not true, and certainly did not explain why they ended up paying that money to a party who was not entitled to it.

- Who the f–k knows?

On August 9, 2022, CONNECT sent out an email to its members advising that CONNECT would be charging an admin fee of 14% on top of the admin fee of 18.7% being retained by Re:Sound. Between the two, that amounts to 33% in admin fees. One third of our money! Now, I understand what Re:Sound does and why they deserve to get paid. But CONNECT? That I’m not so sure about and no one else seems to be, either.

So if CONNECT is not involved in the collection process in any meaningful way, doesn’t work to ensure its members get paid properly, and just acts as a conduit for revenues, then what is the consideration for the admin fee? What’s the service that CONNECT provides? What is the quid pro quo? Had CONNECT put as much effort into finding our revenue as they did into making excuses for our lost revenues, that money would have been found. It was infuriating that we paid CONNECT substantial service fees, but had to do most of the heavy lifting to figure out the problems.

There’s more. It turns out that CONNECT doesn’t even distribute neighbouring rights on behalf of the major labels. Since 2016, the majors collect directly from Re:Sound. Technically, indie labels can go directly through Re:Sound but the fees charged by Re:Sound in that scenario are so high as to be prohibitive, thereby making CONNECT the only financially viable option for indies.

So why is the entity that represents most indie labels controlled by the major labels? And why are majors able to collect directly from Re:Sound while indies are effectively forced to go through CONNECT (thereby paying two admin fees, one going directly into the pockets of the majors)? How did this happen? Who established these fees? Presumably they did not just magically fall out of the sky.

I was not on the inside of how this was all set up. Therefore, I have a number of questions: in whose interest is it for the system to be set up this way? Who benefits from this? The majors own and constitute the majority of the board of CONNECT, and, while a non-profit, the board of Re:Sound had significant overlap with the board of CONNECT during the time we were working with them. Do the major labels control the regime by which indie labels are paid neighbouring rights royalties? Have they used their power to manipulate the system in their favour, to the detriment of the indies? What other explanation could there be?

Artists are also entitled to a share of this public performance money, and that side of the business is also in chaos. While researching this story, I learned there’s an ongoing lawsuit between ACTRA and Re:Sound. ACTRA is a trade union but through its Recording Artists Collecting Society, collects and distributes neighbouring rights royalties to artists. The ACTRA lawsuit is worthy of its own article, but it illuminates many of the issues regarding CONNECT. ACTRA accuses Re:Sound’s directors from the major labels of “us[ing] their power over Re:Sound to ensure it serves the Major Labels’ financial interests,” to the detriment of independent artists and collective societies.

As for SOPROQ, while I do not love having to pay admin fees to both SOPROQ and Re:Sound, at least the SOPROQ admin fees are reasonable (significantly lower than CONNECT). More importantly, SOPROQ have earned their admin fees. We have had more conversations with the SOPROQ team in the last 18 months than we had with the CONNECT team in the 23 years we were with them! In recovering our lost royalties, SOPROQ provided a valuable service that we were more than happy to pay for – even if necessitated by CONNECT’s failures. The data that SOPROQ used to calculate our royalties was the same data CONNECT had. So why was CONNECT unable to identify and collect revenue that SOPROQ was able to find with relative ease?

Recently, when I was aggressively advocating on 604’s behalf with CONNECT, CONNECT pointed the finger at Re:Sound, suggesting our issue is with them. The thing is, we don’t have a contract with Re:Sound. We have a contract with CONNECT. If we have a cause of action, it is against CONNECT, not against an entity with whom we have had zero contact and no privy of contract. More disturbingly, the people at CONNECT telling me the real culprits were Re:Sound were many of the same people on the board of Re:Sound!

As of Jan. 1, 2025, CONNECT is out of the neighbouring rights collection game, with SOPROQ representing independent rights owners. CONNECT will represent Canada’s major labels while continuing to provide licensing for the industry. They are framing it as a “new partnership” with SOPROQ, but those in the know say CONNECT will be completely removed from the neighbouring rights business and the partnership is completely about optics. Is CONNECT actually going to make sure all independent labels have received all monies due to them before they get out of the indie neighbouring rights business as they say they will? If not, what recourse, if any, will there be for indie labels to identify and recover lost royalties?

We at 604 are lucky to own some masters that generate significant revenue. But what about indies who are not so fortunate? This loss of revenue could be devastating.

If indie labels expect the major labels to step up and do the right thing, they are waiting for Godot. As 604 continues to work with SOPROQ to recover our revenues, I have been sounding the alarm bell at CIMA and with as many indie labels as possible, as I am sounding the alarm bell here and now. Indie labels: Go get your money!

Let’s not forget that the money being collected is, in essence, trust money: money being collected and held on behalf of another party. We need to have an entity in place that treats this job with the respect, gravity and independence that it calls for.

What is the moral of this story? Lesson One: if something feels wrong, it probably is, so get off your ass and do something about it. Ask questions. Demand answers. I should have paid more attention from day one. When the money was rolling in, we were blissfully ignorant and happy to cash the cheques. It was only when the payments started to plummet that I started asking questions. I wish I knew then what I know now, about the backdrop of self-interest and redundant management. I would have done everything in my power to remove the middleperson (i.e. CONNECT) or renegotiate the admin fee.

604 is currently considering all legal remedies to seek repayment of the admin fees we paid to CONNECT and encourages other indie labels to do the same. The last thing we want is a lawsuit, but there may be no other clear path for indie labels to assert their rights or identify problems, let alone resolve them. CONNECT (which is to say, the majors) needs to do the right thing and repay some or all of these service fees to the indies.

If I can quote my business partner, what we need to do to the current system is burn it to the ground. Then, we can replace it with something new that makes sense – a system without unnecessary middlepersons.

Jonathan Simkin is the president and co-founder of 604 Records, which is one of the biggest independent record labels in Canada. Prior to starting the label in 2001 with Chad Kroeger of Nickelback, Simkin was the band’s attorney, a role he still has today. 604 is known for multiple international hits, including Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe,” which Simkin co-executive produced.

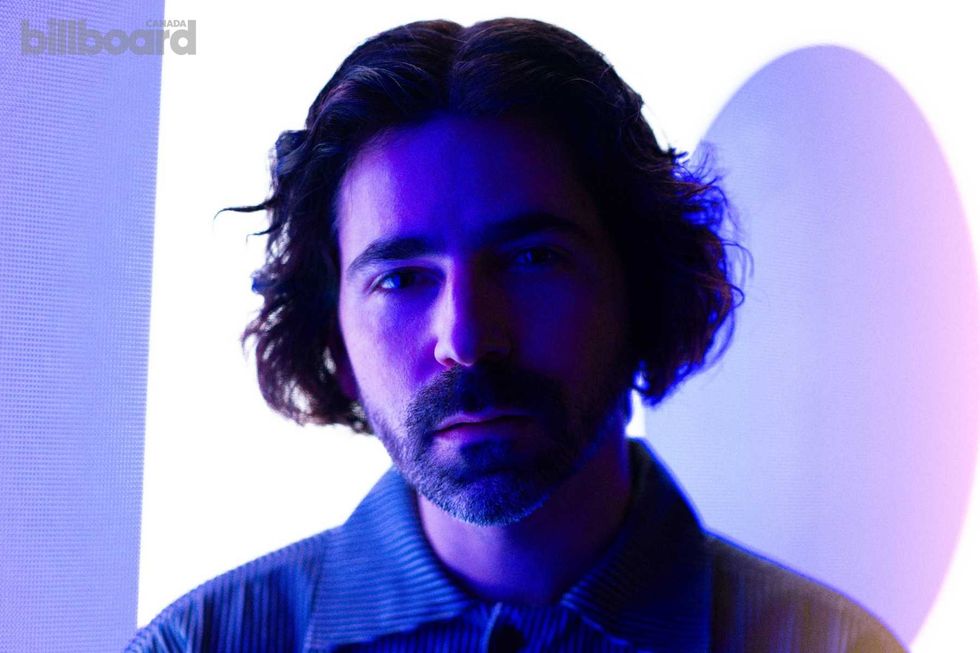

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026. Lane Dorsey  Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey

Felix Cartal shot at the W Toronto on Feb. 20, 2026.Lane Dorsey