Ticketmaster's Jared Smith Has Remedies To Nix $8B Scalper Biz

Smith says the bot biz has been growing in double-digit percentages every year for the past 10 years in North America, and his company is fighting back.

By Nick Krewen

As the province gets ready to introduce the Ontario Ticket Sales Act on July 1, banning scalper bots and capping ticket resale pricing to 50% above the face value of a ticket, many have serious doubts the legislation is going to have the desired effect the government is hoping for.

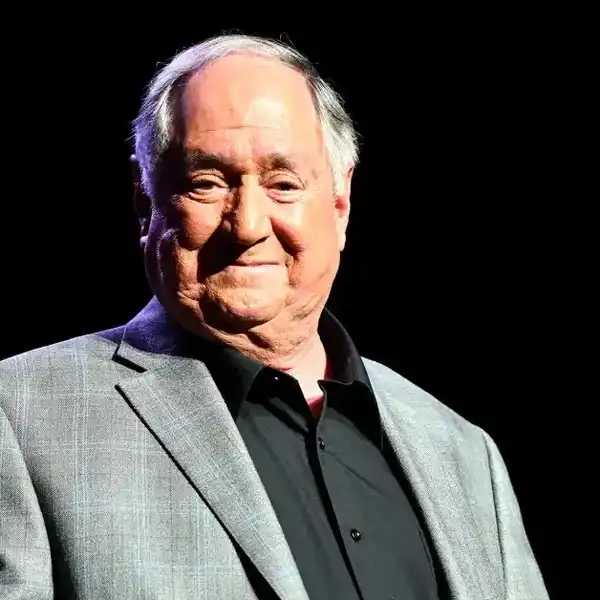

Among the sceptics who feel the move will be ineffective is Jared Smith, the president of Ticketmaster North America.

“I think there’s definitely a place for public/private partnership in solving some of the industry issues, but I don’t think that a lot of things outlined in this piece of legislation are going to be enforceable,” Smith told Alan Cross during a Canadian Music Week interview at Toronto’s Sheraton Centre last week.

The Ontario Ticket Sales Act was partially a response to disgruntled consumers complaining about being unable to grab tickets for the final Tragically Hip tour in 2016, although, with four million people vying for 200,000 tickets, the math wasn't going to work out in their favour necessarily. The fact that tickets showed up on secondary ticket market resale sites shortly after going on sale didn't alter the perception that something was wrong with the system.

But, as Smith notes, the laws of supply and demand dictate that sometimes people wanting tickets for certain high profile, in-demand acts are going to be left out in the cold, "because of sheer numbers. Somebody’s going to be disappointed."

Aside from that reality, Smith admits that the ticketing profession is “one of the most confusing, misunderstood portions of the music business,” but says this pending Act isn't the answer.

“There have been resale bans and ticket caps in places, and it hasn’t been successful,” he notes. “To be effective, you have to go after individuals, and I don’t think it’s going to work. What it’s going to do is hurt local ticketing businesses.“

Smith, who says scalping is an $8B practice in North America alone and has been "growing in double-digit percentages every year for the past 10 years," says there are a number of solutions Ticketmaster is employing to fight the problem.

"Ultimately what the problem is – there’s a disconnect between what the product is worth and what it is sold for. Generally speaking, we undervalue the best seats in the house," concludes Smith, who has been with Ticketmaster for 15 years, the last five as president.

He says that one of the solutions is to charge a premium ceiling that makes it unattractive for ticket resellers to remain in business. The other is to come up with a digital technology that eliminates the paper ticket, the bar codes and thus prevents transfers and forgeries, which the company has with TicketPresence.

"I could do one of two things to solve the problem: I could price it right and charge $500 for it," Smith explains. "Because if it’s $500, they won’t have the incentive to buy it because they won’t make any money. Or, I could use a technology that if you buy it and the price is too low, it can’t be flipped. Those are the only two ways to resolve this.”

And, of course, there is the bot problem: digital robots that employ artificial intelligence grab tickets as soon as they go on sale and heavily reduce the chances of tickets getting into the hands of a fan.

"The reason that the bots are so pervasive and they’re so sophisticated is that there’s so much money to be made," says Smith. "It’s dead simple. The point is, the bots are buying the tickets because they’re liquid. And they can sell them anywhere they want to sell them because they’re not digital."

Explaining the problem of continuing to work with paper tickets, Smith says that, "we haven’t figured out, as an industry, how to get a ticket into the hands of a fan at the price that the artist wants. The reason we haven’t done that yet is because the tickets are 100% transferrable and 100% anonymous. I can buy it and give it to you, and the system doesn’t know that it changed hands; the system also doesn’t know whether your bar code or my bar code is the true bar code. Whichever goes through the venue first is going to win."

The Verified Fan program is one solution.

"Let’s have all of those people sign up beforehand, and separate the time that they register from the time that they purchase," Smith explains. "While we take our time to identify if someone is a bot or a cheater or a fan, we do that process asynchronously. We don’t try to do it at the same time. Once we identify who those fans are, then we don’t put them in an on-sale at all: we give them a one-time use code, and we text them their tickets and say, do you want to buy these?

"You take that crush of a one-size-fits-all, and you break it up into these stages where you can better take time to identify who your real fans are, make sure they have a good experience and try to sell it that way. And if you can’t sell those tickets, at least manage your expectations, so they’re not sitting there wondering if they’re going to win the lottery and get mad when they don’t. Because sometimes it’s a numbers game."

Other interview revelations:

Ticketmaster's sole source of revenue is the convenience fee or at least a portion of it. "Not only is that the only way we make money, but we also don’t even make that exclusively," says Smith. "We bear the burden of the cost of the developing of the software, the support. all of the hardware, including scanners, the ticket printers, the computers – all of that stuff – and we’re in the hole for all of that cost until we can secure a contract, sell a ticket, pay the share of that convenience fee to whoever owns the rights - i.e., the venue." Smith says Ticketmaster collects between 15%-20% of the ticket's face value but retains "a less significant percentage," which he estimates ranging from $2-$4 a ticket, "depending on the deal."

advertisementTicketmaster has been purposely foggy when it comes to behind-the-scenes machinations. "It’s a function of where we sit in the ecosystem," Smith says. "We have neither been excited about nor proactively active in telling the story of what happens behind the scenes, mostly because it’s perceived to be a benefit from the act or the sports team who really didn’t want to have that portion of the business exposed on how it works. So, it has become a service that we provide in the role played: if there were pricing problems or there was a difference between supply and demand, there is stuff that is tough to explain. It’s easier for Ticketmaster to take the brunt (of criticism) than for me to be honest and upfront."

advertisementTicketplus integrates both primary and secondary ticket sales into its business model. "For a long time, the company – not necessarily me – thought the strategy of separate primary and secondary selling markets was the way to go," says Smith. "Now, we think the opposite. We think that having primary market tickets over here and secondary market tickets over there creates all kinds of opportunity for fans to be confused and taken advantage of. Now when you show up at Ticketmaster.com, our retail experience today is on the page where you look at primary tickets. A blue dot on the seating chart is a primary ticket, and a red dot is a resale ticket.

Ticketmaster doesn't have a problem with ticket brokers, "as long as they're not cheating," says Smith.

Ticketmaster purposefully won't tell you how many tickets are available for a show. "It’s not a question of that we can’t - we certainly can," asserts Smith. We shouldn’t. We don’t think that it is consumer friendly. Shows fall into one of two categories: They are either wildly in-demand, or you could stroll up four days or 40 days after the on-sale, and there is plenty of inventory. The first category is a very small portion of the show. The vast majority of the shows – it’s hard to sell tickets. So this idea of disclosing how many tickets are on sale to the general public for 95%-98% of the shows is irrelevant."