A Summer Read About Tommy James' Me, The Mob & The Music

It’s August and time for that good fun summer read.

By Bill King

It’s August and time for that good fun summer read. With the world in chaos and senseless jabbering polluting at every turn, a sure-fire moment of cool-down time is a fine book, a summer breeze, and mental solitude.

My son Jesse and I are huge fans of music industry biographies. Some fare better than others. Years ago, I passed him a copy of Fredric Dannen’s Hit Men: Power Brokers & Fat Money inside the Music Business and insisted he read. I lived the details recalled in those pages. Jesse? Fascinated! Time in between we’ve shared Bob Dylan’s masterpiece Chronicles; Keith Richards' brilliant; Life– the insightful Here, There & Everywhere: My Life Recording the Beatles by the late Geoff Emerick; The Last Sultan: The Life & Times of Ahmet Ertegun – and still to come: Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968, bt Ryan H. Walsh, Jeff Tweedy's memoir Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back), Michael Diamond's Beastie Boys Book

One short read Jesse suggested a few years back - a terrific expose he insisted I stop everything and get lost in – Tommy James: Me, the Mob & the Music, co-authored by Martin Fitzpatrick.

When the car radio was king it ruled with an ironclad song. A concise two minutes and thirty seconds of aural pleasure. A message summed up in a catchy phrase and pinned to an infectious melody only the cleverest invent.

At one time there were specialists holed up in office buildings – a piano and ideas as if a new campaign was being waged on behalf of chewing gum or fashion or ache cream.

Popular music arrived in the ‘50s just as World War II was backing away. A new generation was liberated from the soothing rhythms and mellow tones of dance bands that aided in mending injury, loss, and great sorrow. The music tended to a nation heading back to work and gradually healing. The new sounds came from all directions. Most still influenced by American folk culture.

Pop music is about mass appeal - a smart hook – a pleasurable moment, steady backing rhythm and escapism from a demanding day ahead.

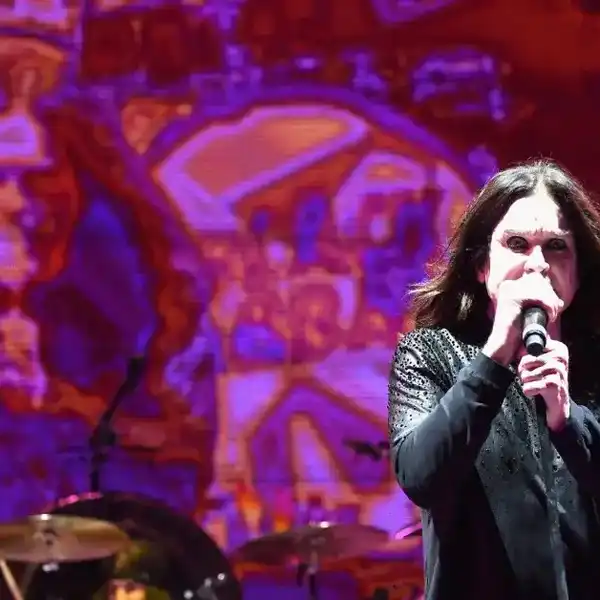

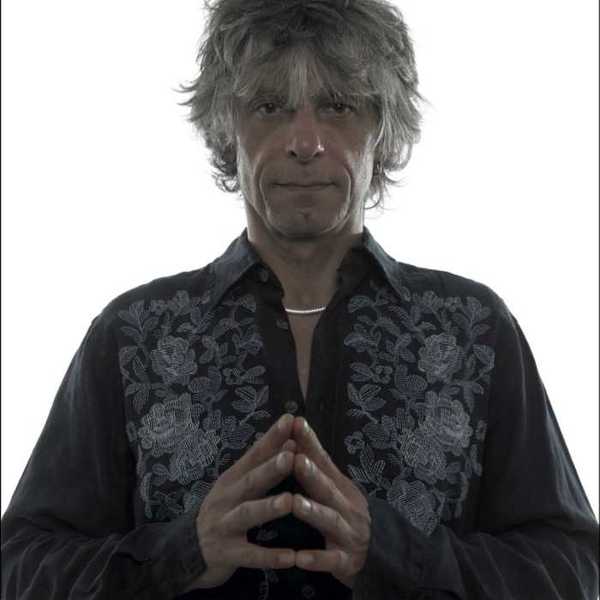

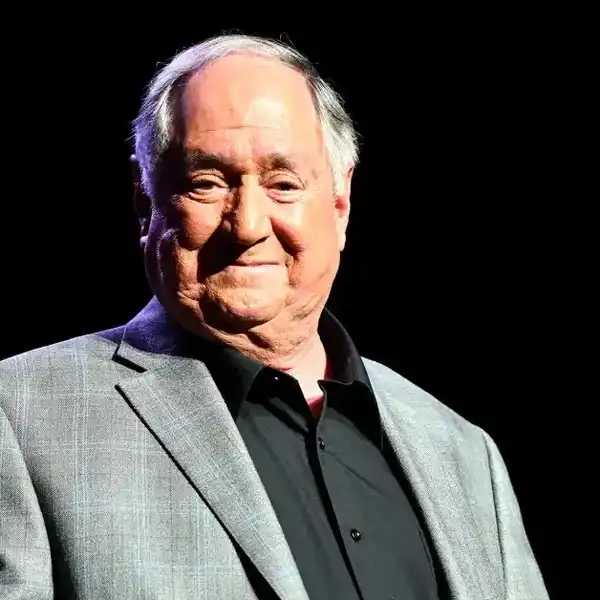

One of the most successful icons of the era, Tommy James still finds joy in those songs. The re-singing, celebrating and retelling to an audience whose perceived best moments were in their teens when all seemed possible, loving was less complicated. Passion burned at a temperature well above the sun’s core and friends gathered to spill half-truths about outsiders.

There have always been grey zones in the music business. On the march to the top those subtle tones meld together. One-sided contracts arrive with little to cheer about – especially for the artist. The early day’s business was something musicians thought businessmen did, and artists made art. Lost in that relationship were the profits to be made. Most acts whither before climbing the first rung on the ladder – others like Tommy James scored big early on and then sorted the finances out much later. There are no real good guys – plenty bad ones but somewhere in between is common ground – and a score is a score. Tommy has a great story to tell and hit records to back it up.

I spoke to Tommy a few years back, and that conversation still plays in my head. Enjoy.

Bill: It must be gratifying after fifty years in the business to have better times just keep coming?

Tommy: It’s been an amazing fifty years. I never in the world thought we would be here. Rock and roll is a business that may give you two or three years if you’re lucky. I thank the good Lord and the fans for this kind of longevity.

Bill: You were able to rebound from the legal issues with Roulette. Were you able to get the copyrights and masters back?

Tommy: I have publishing on everything after Roulette. As a matter of fact, we’ve done a major deal with Sony. Sony has ended up with publishing on the Roulette material through a series of big fish-eating smaller ones. Sony just recently purchased EMI. I just did a deal with Sony to administer our publishing, which was everything after 1975. All my music is under one roof now represented by Sony. It’s great. Sony can do things as a global publisher we couldn’t. They are doing all of our licensing for movies, television, and commercials and collecting royalties all over the world.

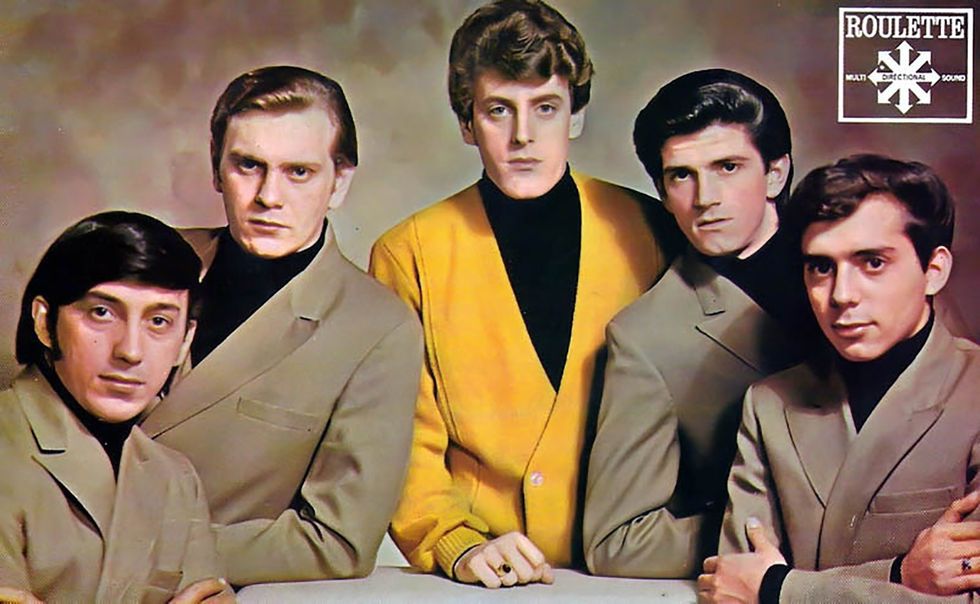

Bill: When you had your first hit Hanky Panky - there were others like the McCoys with Hang on Sloopy, The Castaways Liar, Liar, and The Shadows of the Night - Gloria, all northern mid-west bands coming with these great regional hits that eventually broke nationally then worldwide.

Tommy: As I reflect on all of this from back then I’m amazed at the evolution. You are quite right – we broke out of Pittsburgh, and that could never happen today because of radio being the way it is, and the Internet has brought massive change. Back then every small town had its own music business as did every major city. If you did break out in a major city, you’d hit the trade papers and have a chance to go national.

Bill: I’ve read your book – a fascinating read. It must have been a challenge going to mobster Morris Levy as a young man knowing you are selling millions of records and taking in account the power this man wielded and asking for a fair accounting and royalties?

Tommy: When I first came to New York, we’d had the regional breakout hit and I’d just turned nineteen. We had a yes from Columbia, Epic, RCA, Kama Sutra. The bottom line was we had a yes from everybody and the last place we took it was to Roulette, at the very end of the day. I went to bed that night in 1966 thinking we’d probably go with CBS, RCA or Atlantic. The following morning, we started getting calls from the labels and they said, “Listen, Tom, we’re going to have to pass.” I said, “What do you mean you’re going to have to pass?” And finally, Jerry Wexler at Atlantic told us the truth. Morris Levy of Roulette had called all the other labels and backed them down and scared them and said, “This is my record.”

It was the first offer I couldn’t refuse. But I can tell you right now if we had gone with one of those other labels, especially with Hanky Panky we would have been one-hit wonders. We would have been handed over to an in-house A&R guy and immediately get lost in the shuffle. We would have been lucky to have one hit. Roulette needed us. They hadn’t had a hit in three years and from a creative level, we probably couldn’t have picked a better situation. They basically gave us the keys to the candy store. We had complete control over our careers. I was allowed to put a production team together, which would have never been possible with a major label.

Bill: Do you think Levy had great ears for a hit record?

Tommy: Morris Levy was the president of Roulette Records. Nobody knew singles like him. The relationship we had with Roulette was phenomenal, and we ended up selling over 100,000,000 records. Twenty-three gold singles – nine platinum and gold albums. At a creative level we couldn’t have done better, but doing business with them was a disaster. It was like taking a bone away from a Doberman getting paid. We constantly asked ourselves was this worth it. Do we take our lives in our hands and go to another label and get out of this thing legally (contractually) or do we stick it out at Roulette where we are having such great success? It was not fun – always confrontational – there was always this real kind of threat behind everything if you complained or talked too loudly. We made the correct decision and stayed, and I don’t think we could have gotten out of that contract.

Bill: Did you sign for five years a standard contract?

Tommy: Actually, a ten-year deal. I could have never gotten the education in the music business any other way – we would have never had this success. Plus, it’s a good story.

Bill: It’s the underbelly of the business with all the trimmings.

Tommy: On the dark side behind the scene was this very cold and sinister story we couldn’t talk about. Roulette was being used as everything from a social club by these wise guys – money laundering – running drugs through there and as a front for the Genovese crime family. We had to pretend we didn‘t see this stuff. We’d see characters up in Levy’s office, and two weeks later they’d be taken away from a warehouse in New Jersey in handcuffs.

Bill: That’s kind of the history of many small independent labels that got funding from unsavory sources.

Tommy: You know all you had to do back then was reach those twelve major radio stations with an outreach of thirty million listeners, and you’d cover the entire United States. Every band had a story and a million-to-one long shot like ours. Ours was a miracle, and the longer I’m in this business, the more I recognize that.

Bill: How did you pull together the first record?

Tommy: The group that became the Shondells were called the Tornados when I was twelve years old. I got a job in a local record shop, put together my band and played all over the area as a cover band for years – all through junior high and high school. We had two little label deals before – one when I was fourteen, the other when I was sixteen. Both through the record shop. The first was a one-stop distributor out of Chicago that had a label and sort of enlarged our territory with that. The second, where Hanky Panky came from, was a local radio station in Niles, Michigan that was going to do a label. One of the four sides I recorded for them was Hanky Panky - the version that became the hit.

Bill: Where did you find the song?

Tommy: I had heard and seen this other band play it. I also saw the reaction of the kids to it. It was amazing – I’d never heard the song before. All I could remember was My Baby Does the Hanky Panky – that was the whole song. This was right at the beginning when we signed with Snap Records. We went into the studio and recorded it and I had to make up some words – I could only remember My Baby Does the Hanky Panky – made up a middle section and put it out locally and it did really well, but we didn’t have any distribution, and it was 1964.

I graduated from high school in 1965 and took my band on the road. We played on Rush Street in Chicago and got an agent from the city and started playing up through the mid-west. Then in early 1966, we are playing this dumpy little club in Janesville, Wisconsin and right in the middle of a two week booking the club owner goes belly up and gets shut down by the IRS for back taxes. We were lucky to get our equipment out of there and drove back home feeling like losers cause that’s how the good Lord works. The minute I get home I get the call that would change my life. A local disc jockey in Pittsburgh was playing Hanky Panky and got this incredible response – bootlegged the record and sold 80,000 copies in ten days and we were sitting at #1 in Pittsburgh. They had to track me down, and of all places called the record shop I used to work at and they gave them my number. Now, if I hadn’t been home when the call came – you and I wouldn’t be talking right now.

I went to Pittsburgh – I couldn’t put the original band back together so I grabbed the first bar band I could find and called them the Shondells.

Bill: Back then a lot depended on that marriage between the artist, local disc jockey, and record store.

Tommy: Disc jockeys were local stars. You had the bigger markets and secondaries.

Bill: What about the live show now – mostly the hits?

Tommy: We do a lot of the hits and some written for the new movie.

Bill: How’s that going?

Tommy: Very well. Barbara Defina – she’s had a run of successful films. She’s produced Goodfellas, Casino, Cape Fear and The Color of Money, among other films. She has the financing – the screenplay is there – they will be choosing a director shortly – we are right on schedule.

Bill: Are you a fan of these kinds of biopics? Any stick out?

Tommy: I heard Jersey Boys is going to be good. I haven’t seen it, but I’ve been to the play twice. It took them ten years to get that done. Most re-enactments of the sixties I haven’t been happy with. I liked Ray. I am looking forward to it all.

A Music Business Anecdote from Bill King:

I don’t know how true this music fable is, but it sums up the mob vs. artist relationship.

A ruthless record company president is sitting in his office when a commotion ensues in the lobby of his business. “You can’t go in there – I’m telling you the boss is in a meeting,” says the secretary.

The angry African American singer comes to collect back royalties wielding a loaded gun. “I’m going to the kill the motherf.. He’s got my money and he’s gonna die.”

He then bursts into the office and confronts the mogul and his attorney who are sitting together doing what conniving paperweights do.

“Whoa, man, slow down,” the mogul says.

“I want my money you son of a bitch – pay me now. You’ve been stealing and lying – I sold six million records, and you haven’t given me a dime.”

The mogul coolie reaches down in his pants pocket and reveals a money clip loaded with a wad of bills - a couple hundred strategically fitted on top of a series of ten, dollar bills.

“Man, I’ve got your money right here – been meaning to pay you. Been packing your money around for months.”

The mogul undoes the money clip and places the fat wad of bills on the table. “Take it – it’s yours.”

The artist thinks for a moment then grabs the pile. “When do I get the rest?”

“Soon man! Look – see that Cadillac out there – here’s the keys – it’s yours. Just bought it the other day.”

He then rolls keys across the desk.

A minute passes before the suspicious singer sticks the gun back into his belt – nods, and heads out the door.

“Son of a bitch – you amaze me. He could have killed us,” says the attorney.

“Yeah, I know.”

“Honestly, you are a wizard. When did you buy him that Caddy?”

“I didn’t; it’s a rental.”

Amen!