Reversion Rights Needed In New Copyright Act

Taylor Swift has been making headlines with her outrage over the acquisition of her past masters recorded for Big Machine Records.

Taylor Swift has been making headlines with her outrage over the acquisition of her past masters recorded for Big Machine Records.

By David Farrell

Taylor Swift has been making headlines with her outrage over the acquisition of her past masters recorded for Big Machine Records.

Her case for self-determination is confusing. She was aware the Nashville-based label was seeking a buyer, and, as such, she could have approached owner Scott Borchetta with a bid to acquire ownership of the master rights to her catalogue.

Borchetta could have refused any offer she made for ownership of her six albums as in his doing so would have devalued and perhaps even impaired his ability to sell the label and its assets.

No short of a penny, Swift could also have made an offer to buy the company outright. The back-and-forth played out by Swift across various media makes it unclear as to whether any prior discussions ever took place.

The feud is not over. Still, it brings to the fore similar cases I have become knowledgeable about from interviews with Canadian artists who have had hits and sold a lot of records at home and around the world over the years. Specifics are not possible as it is impossible to glean all the information relating to the artist contracts without actually seeing them.

Artist A recorded more than a handful of albums for a label, which was sold to another company that eventually went bankrupt. The catalogue, and others affiliated with the same company, were acquired by a newco in the early ‘90s.

Artist A claims royalties have been paid, but is unsure if the amounts are correct. Artist A also suggests that there have been difficulties in getting sync clearances approved by the company, even as both the company and the artist stand to gain from these approvals.

Digging around, I found out that Artist A’s original contract possibly included a reversion clause that should have kicked in years ago. Unfortunately, the company now in possession of Artist A’s master recordings acquired them as is, without also obtaining the contract that spelled out the term of duration and other caveats. Sadly, the lawyer who wrote up the contract, and the manager who would have had to approve it, are deceased. Artist A has no record of that contract, so the ownership question remains ambiguous.

My knowledge of the reversion clause was gleaned from a verbal discussion with someone aware of the initial contract's details; however, this person does not have a copy of the agreement, so at best it is hearsay.

The issue here is to change the law so that master recordings cannot be acquired without corresponding contractual documentation. It can also be argued that, on moral grounds, the artist master rights should only be re-assigned subject to the artist having advance notice, and an opportunity to acquire them at an adjudicated fair market value.

Artists B and C had successful recording careers with a label that was subsequently sold, and all the master recordings transferred to a new entity. Artists B and C were never notified of an impending sale and therefore never had the option to acquire the master rights, which would have significantly benefitted them.

Both artists tell me that if the opportunity had been on offer, they would have found the money to buy the master recordings of their works. They, too, have difficulty in getting sync licenses approved from the company that now owns the master recordings.

Artist D has another story entirely. Artist D had a successful career as a recording artist with a label that received a significant advance from another company as part of a P&D deal. The deal defaulted when the original company Artist D was signed to defaulted, and rights to the masters automatically became the property of the company that paid the advance. Or at least until the advance was recouped.

Information provided to me suggests that the advance was long ago recouped; however, the catalogues from Artist D's original label were subsequently purchased by a third company. I am told that royalty payments are regularly paid; however, the ownership of the masters continue to be owned by the third party when it is possible the artist could rightfully have ownership by now.

The artist tells me that the fighting days are in the past. That the focus now is on playing music and enjoying that part of the creative process. Since royalties are being paid, the thought of hiring a legal advisor and pushing for answers to rights of ownership have come and gone.

Notable, too, is the fact that three of the five labels Artist D's catalogues have appeared on no longer exist, and yet many of these recordings can be found on streaming services and, in varying degrees, available for sale online.

Summing up, one of these artists wrote me recently, stating: "I've owned every one of my master recordings for the past 20 years, and I've made 11 albums since. I license to others from my company, and I make money now, despite the industry changing so dramatically in the past decade. I don't invest any time feeling bitter about it....I've had way too much fun in the past few years writing and recording new albums. I just keep moving forward, creating music that I do own."

Whether any of these issues set out above can be resolved with new safeguards embedded in Canada’s future copyright laws is not something I can answer. Still, safeguards need to be in place and, at the very least, there should be some easy process where matters of contract law can be resolved without the punitive cost of litigation.

The issue isn't just over ownership of the masters, but also about the availability of the catalogues, who is benefiting from streaming and radio performance income, and rights over how songs are licensed in commercials, on TV and in movies.

Most of the artists interviewed above have given up the fight for regaining ownership and tell me their focus today is on live performance, which provides far greater satisfaction than fighting the system, and they also acknowledge that artist contracts from the eras of LPs and CDs were written to benefit the labels in the long-run. They mostly say that the catalogues helped make them who they are today and they would rather let bygones be bygones. In other words, c'est la vie.

The bottom line is that too many master recordings change hands without much accountability, without consent of the artists, and without any guarantees that future royalties will be paid as transparency in these matters is often lacking. It wouldn't be a stretch to say that some of the biggest companies have so many catalogues that have been acquired over the years that specific knowledge of what is in them, and even where they are, is daunting even to them. Because of this, artist requests to these big companies often fall on deaf ears or take forever to be responded to. In many cases, the cause isn't indifference so much as too few bodies trying to manage too many requests and having insufficient information about the titles to respond with any certainty.

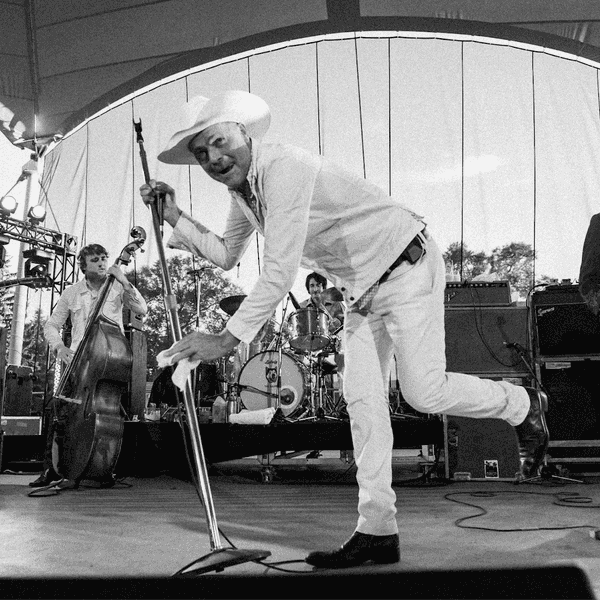

An example of this can be found in a June 2019 article appearing in the New York Times that recounts the difficulties Bryan Adams had in finding archival material from his A&M era that is now owned by the Universal Music Group. His dissatisfaction in trying to find materials from his own legacy isn't specific to UMG. Artists the world over have found their catalogues bought, swapped and sold over the years and following the paper trail has become difficult. And too, over the years, a lot of the materials and even master recordings have been lost, destroyed or simply disappeared.

Last year, Adams appeared before House of Commons heritage committee to argue for a change in the law, fixing the term a company can have exclusive rights to a musician's work to 25 years following its release. As it stands now, the length is 50 years after death, and with ratification of the new NAFTA, it is likely to be extended to 75 years.

Please feel free to respond to this article by sending an email with 'Contract Law' in the subject header to david@fyimusicnews.ca