Five Questions With… Mike Boguski

Blue Rodeo’s keyboardist for the past decade, he is branching out with a solo instrumental album. Here he describes its creation, his openness to free improvization, and his hope for the subsidization of live music.

By Jason Schneider

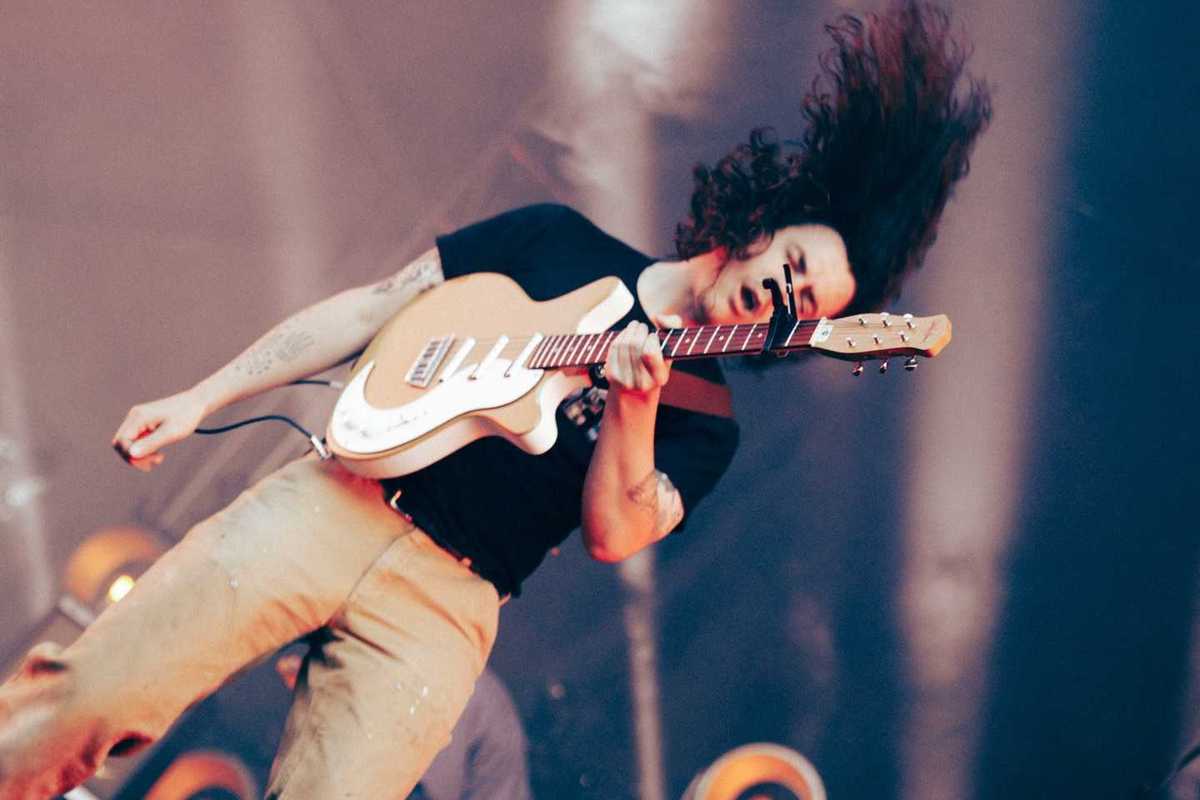

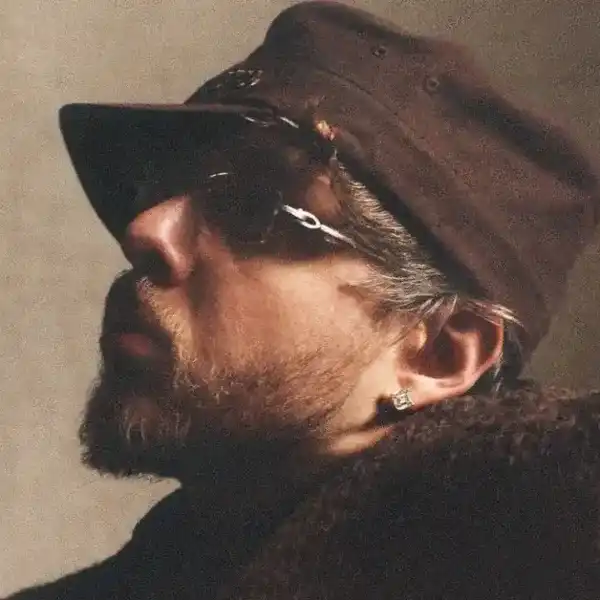

Mike Boguski is Blue Rodeo’s keyboardist, a position he’s held since 2008. But, like others in the group, his musical ambition extends beyond furthering the legacy of Canada’s roots rock institution.

Boguski’s new solo album Blues For The Penitent is perhaps the purest display of his talent to date, showcasing him alone at the piano on 12 instrumental pieces which, taken as a whole, tell a powerful, emotional story. It is a story that unexpectedly developed over a three-year period through sessions recorded by Cowboy Junkies founder Michael Timmins at his Toronto studio, along with sessions at Catherine North Studios in Hamilton, Ontario.

Boguski originally intended to lay down an album’s worth of material in a quick two-day burst, but that plan ultimately changed as major upheavals in his life began to unfold, and led him to explore improvisation more deeply than he ever had previously. It even prompted him to return to school and study with pioneering improvisational musician Casey Sokol at York University.

While many of the pieces on Blues For The Penitent are indeed constructed on the principles of free improvisation, the album is also built around themes and imagery obviously close to Boguski’s heart, such as “Madawaska Moonlight” and “Crossing The Lake,” along with a couple of beautiful renditions of Townes Van Zandt’s “To Live Is to Fly,” and Neil Young’s “On the Beach.”

Boguski is excited to work again with Blue Rodeo in 2019, but he also feels Blues For The Penitent is the beginning of a new direction for his own music that will take both he and listeners to unexpected places. Find out more at michaelboguski.com.

What makes Blues For The Penitent stand apart from previous music you’ve made?

Several pieces definitely are about as free as I’ve ever gone. They make use of clusters of dissonance as materials unto themselves. The use of the piano as a percussion instrument—incorporating the sound of the bench, playing the inside strings of the piano with my fingernail—are all a bit more avant-garde than I normally would go.

Which pieces on the album are you particularly proud of?

I’m particularly fond of “Exitus No. 2” and “Crossing The Lake.” Both are completely free improvisations—I had no idea what the next note was going to be, and I was not playing to any pre-determined set of chord changes. This sounds easy until you try it! “Exitus No. 2” makes use of unresolved dissonance, but in a coherent manner like Stravinsky would, whereas “Crossing The Lake” is pretty straight, using basic triads, but melodically moving into different modalities and moods. Both are definitely departures from how I would previously approach soloing and I’m quite happy with the results.

How would you describe your artistic evolution?

It’s been directly tied into the sudden changes that occurred in my life over a very short period of time. In 2013 my dad died, and six months later my wife at the time left me. I have two small kids, plus I was on the road quite a bit. All of that nearly knocked me out. I was so disoriented that I actually quit Blue Rodeo for nine days. Thankfully, they understood that my mind was out of sorts and they let me back in. It may have ended up being one of the biggest mistakes of my life.

Once I rebounded from everything, I began to realize the futility of having “everything all worked out and perfect.” Whatever plans you make in life can come crashing down pretty quickly, so you better have the ability to react to sudden changes just as quickly, and turn those changes into potentially meaningful points of departure. That is the essence of free improvisation. Once that connection was made, I really couldn’t play straight music any longer. I love playing with all kinds of people, whether improvising with a group of seven-year-olds, or with my band mates in Blue Rodeo. Everything is valid and meaningful.

Along with all of that, what’s been the biggest change in your life over the past year?

I used to get bent out of shape over stuff like gear, or whether all of the keys on the piano were working. Now I’m oblivious to everything other than my capacity to remain free, and accepting of whatever the current situation is. There is no hierarchy; everything is simply measured by what you choose to make of it. I just did a New Year’s Eve gig where the drummer bailed at the last minute and didn’t bother to provide a substitute. The bandleader found a teenage kid whose experience was probably limited to playing in his high-school stage band. This kid had never heard the material, and he walked on stage and did the absolute best job he could. His willingness to accept the terms of the moment, and make the most of it, were more inspiring to me than whatever technical discrepancies existed. It was an incredible experience. Some people like Toto, and quantizing parts that are not perfect. Not my bag, I like the imperfect.

If you could fix anything about the music industry, what would it be?

I would create a system where companies like Apple, Spotify and YouTube would be required to subsidize the creation of live music venues. The same thing with music programs in public schools. These companies that are making so much profit from artists should give back in a way that ensures that we continue to have a healthy live music industry.