Eva Cassidy – I Can Only Be Me

Grief, loss, admiration, amazement, melancholy, and heartbreak are a few sentiments one experiences hearing Eva Cassidy deconstruct and resurrect a songbook classic.

By Bill King

Grief, loss, admiration, amazement, melancholy, and heartbreak are a few sentiments one experiences hearing Eva Cassidy deconstruct and resurrect a songbook classic. Sunday night past, with no exception.

We are used to pillaging bots squeezing a rare item of significance in front of our eyes. Sporadically, a glimmer of promise surfaces and invites us in. With Eva Cassidy, I’m always curious about the backstory, childhood, and how she, in my opinion, became the most perfect voice of my generation. Auto-tune has screwed up how we receive vocals. No devotion to purity or talent. Just another building block for sound architects. Nothing personal, nothing memorable.

Sunday evening, during a weekend owned by wild card NFL football, that pop-up in my Facebook feed appeared. Eva Cassidy—the new single, Tall Trees in Georgia, with the London Symphony Orchestra.

The orchestra itself has a long-celebrated history dating back to 1935, when instrumentalists convened at London’s old Scala Theatre in Tottenham Street to perform the music for the new film Things to Come, a moment in time that revolutionized and inaugurated film production history. In 1955, a group of musicians determined the orchestra should work solely on films and recorded Bernard Herrmann’s score for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much. Ahead, The Dresser in 1983, Shadowlands in 1993, and Notting Hill in 1999, yet it is John Williams' score for Star Wars, 1977, that keeps the orchestra in play today.

The pairing of Eva Cassidy and the LSO seems implausible in that she’s been gone since passing from melanoma in 1996, and most of what’s out there has sold millions, untouchable, saintly, and impeccable as is. Why do this? We remember the tampering with Nat Cole and his daughter Natalie’s virtual duet, 1991 Unforgettable, done through modern film technology. Who can forget the Kenny G pain exacted on Louis Armstrong’s, Wonderful World, 2013? Stay out of “Pops” lane, Mr. Love Sax!

February 3, 2023, marks the 60th birthday of Cassidy. Since November, the estate has released a series of tease singles, leading to the full release on her birthday. Stevie Wonder wrote the little-known title track, I Can Only Be Me. The recording will be available in high-definition stereo, Dolby ATMOS, and Sony 360 immersive audio formats. The songs are all from Songbird, released posthumously in 1998, and vocals restored using enhanced A.I. technology, a similar process employed by Peter Jackson on The Beatles Get Back series and subsequent Revolver Album. Orchestra arrangements by classical composer Christopher Willis (Twilight Saga, X-Men, The Death of Stalin.)

Fans of Cassidy will view this in a variety of ways. Cassidy’s music is perfect; don’t tamper with how things were done in 1993. It should be her call. Or allow Cassidy the opportunity to surround herself with a full orchestra, something tried but never experienced to this degree in life.

Early on, Cassidy was the talk of her closest friends. The major record labels had declined to sign her. Looking back at the early 90s, you recognise she didn’t fit the glam-rock MTV persona – not a screen beauty bouncing about sequin costumes. More a Carole King, James Taylor’s intimate experience performer of a few decades earlier. Second, she was a song interpreter, not a full-on songwriter. The hit recording, Songbird was written by Fleetwood Mac’s Christine McVie. This is what makes Cassidy more intriguing. Her repertoire borrowed from the traditional: Autumn Leaves, Over the Rainbow – yet it was that choice of outside material that separated her from most cover artists. Sting, McVie, Smokey Robinson, John Lennon, and Rod Stewart.

The music.

The restoration and orchestrations from these ears in no way supplant or overshadow the originals in their ability to grab the heart. Buffy-Sainte Marie’s Tall Trees in Georgia is entrenched in a swirl of embracing violins, cellos, and violas, wrapped around a voice so heavenly even the Gods listen on with anticipation. It’s a journey—that big theatrical production you once heard in sweeping film scores before artificial stings, white noise swoops, gasping choirs, and pounding drums. Watch any of the recent movie trailers, and the effect is confusing—storylines buried under an avalanche of shock and awe editing.

What I find of particular interest are the years before Songbird and Eva’s passing. The untold and rarely mentioned. That connection with DC's Chuck Brown – the king of that Go-Go sound. An artist and innovator, many rank alongside James Brown – his equal. Who can forget Bustin Loose? Many of these questions are answered in today’s podcast.

EVA

By Jefferson Morley - March 8, 1998, Washington Post

“Eva Cassidy had that effect on more than a few people. She had a voice that could silence a barroom and get the pool players to lay down their cues. A voice that could prompt casual listeners to round up their co-workers for a night out dancing. A voice that could invest all kinds of American popular music with a true portion of herself. Pop singer Roberta Flack called her "a master of her craft." Rock drummer Mick Fleetwood longed to record with her. Jazz singer Shirley Horn simply said, "What a voice." She also had a manner that drew people to her -- blunt, insecure, innocent and edgy in some interesting places. She lived and sang in ways that dispelled the obsessions - race, politics, careerism -- that pervades the place where she was born. She was indifferent to conventional notions of achievement. She didn't open a checking account until she was in her late twenties. She had several close female friends, but her mother was the closest. For all the insight she brought to torch songs, intimate relationships with men gave her fits. She craved long walks, bike rides, sleepy old towns and junk food. On perceived matters of principle, she would not compromise. About her talents, she was insecure to a debilitating degree. She was a blonde of Irish and German heritage.

For all its evocative power, her singing was technically perfect. She had to be taught how to snap her fingers onstage. She was a feminist with a particular loathing for the sexual exploitation of women. She was, for a while, dependent on the men who produced, managed and collaborated with her. Performing scared, her Singing sustained her. Reconciling that conflict gave shape to her artistic life. Eva died on November 2, 1996, at the age of 33. Yet hers was not the shooting-star glory of a young woman who never had the chance to fulfill her potential. She had already founded a career on a constellation of polished performances, both live and in the studio.”

I spoke with the man who put things in motion and brought Eva’s music out of the family basement, the marketing and magic behind Songbird and eleven million in sales.

This is where we begin today on this unique FYI Music News podcast!

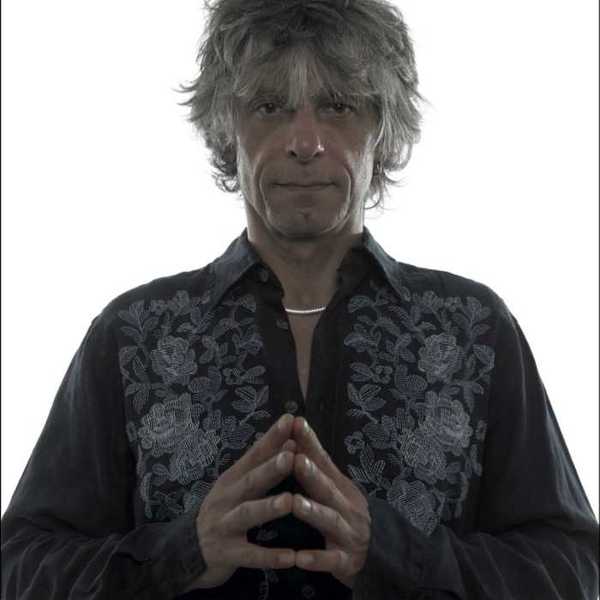

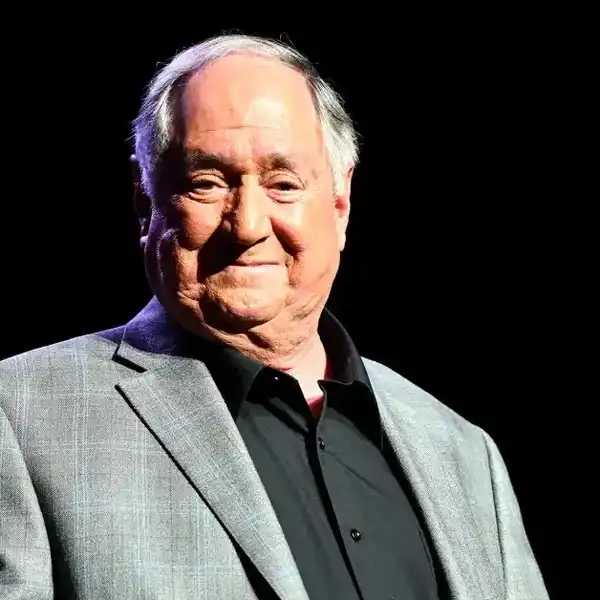

Bill Straw

Before launching Blix Street, Bill Straw, himself a frustrated singer-songwriter, began his career in the legal department of Capitol Records. He moved on to Warner Bros. Records, Shelter and others before becoming general counsel for MCA Records. Eventually, he moved on to Curb Records, where he also formed a label called Gifthorse, distributed by Curb, to house Mary Black’s U.S. releases. When he severed his ties to Curb, he launched Blix Street, naming it after the street on which he lived in Los Angeles. Now based in Gig Harbor, Washington, outside of Seattle, Blix Street continues to release a small number of tasteful recordings each year.